Do you wake up at 3:00 or 4:00 in the morning? Unable to fall back to sleep –or even worse, falling back to sleep an hour before you need to get up?

This article shares the genetic variants that are linked to early waking — and how you can apply that knowledge to get to the root of the problem. Members will see their genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

Early Waking and Tryptophan Conversion

A recent study investigated patients with depression, part of them with early waking, as well as a control group without depression. The study found a genetic variant in the TPH2 gene occurred significantly more often in patients with early waking.[ref]

TPH2, tryptophan conversion to serotonin:

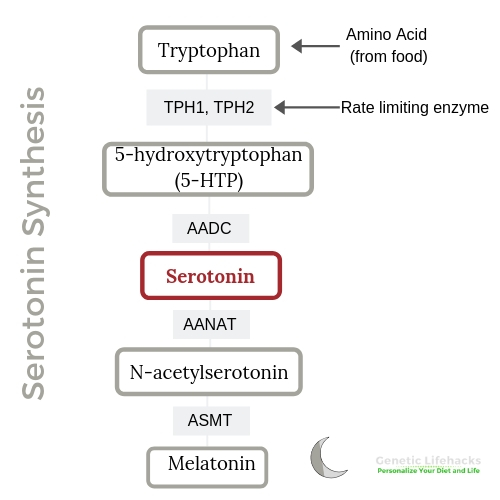

The TPH2 (tryptophan hydroxylase 2) gene codes for the rate-limiting enzyme in the production of neuronal serotonin.[ref] Basically, this enzyme is the key to the amount of serotonin in your brain. The TPH2 enzyme causes a reaction to take place in the brain, converting tryptophan into serotonin.

The categorization of serotonin as a monoamine describes the structure of the neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. Serotonin is active both in the brain and in other parts of the body, such as the digestive system. In fact, most of the body’s serotonin (90%) production happens outside of the brain using a related enzyme called TPH1.

Serotonin produced in the brain acts as a neurotransmitter, relaying chemical messages between neurons. It is thought to be involved in arousal, mood, appetite, sleep, and memory.

Serotonin doesn’t easily cross the blood-brain barrier, so just taking serotonin orally, or eating foods high in serotonin, doesn’t change brain levels of serotonin.

Conversion of tryptophan:

To produce serotonin, your body uses the essential amino acid tryptophan as the foundational building block. It is then converted in the brain using the enzyme TPH2 into 5-hydroxy-L-tryptophan (5-HTP). The 5-HTP then converts to serotonin (5-HT).

If you follow the pathway further… serotonin actually is the precursor for melatonin, which is highly involved in your body’s circadian rhythm. Melatonin is important for sleep onset and possibly for sleep maintenance. (Brain levels of serotonin, though, may not affect melatonin levels since melatonin can cross the blood-brain barrier.)

Here is a quick diagram of the process:

Circadian rhythm in depression and early waking:

While depression is a multi-faceted disorder, at the root of it for a lot of people is circadian rhythm disruption. (Read: Circadian Rhythm Genes: Mood Disorders and Bipolar Disorder, Depression, and Circadian Clock Genes)

One obvious part of circadian rhythm disruption would be problems with sleep. The TPH2 gene variant seems to link together extremely early waking with depression and serotonin.

Impact of TPH2 variant:

The study on early waking and TPH2 in a Chinese population used a group of 249 people. The researchers investigated a number of variants in the TPH2 gene, which has been associated with an increased risk of depression in various different studies.[ref]

The researchers found one TPH2 SNP (rs4290270) was not only associated with an increased risk of depression, but it was also twice as likely to be found in the depressed patients who woke early. The study also found that fMRI images of the brains showed differences in the carriers of the different alleles of this genetic variant.[ref]

Early Waking Genotype Report:

Members: Log in to see your data below.

Not a member? Join here.

Why is this section is now only for members? Here’s why…

Member Content:

Why join Genetic Lifehacks?

~ Membership supports Genetic Lifehack's goal of explaining the latest health and genetics research.

~ It gives you access to the full article, including the Genotype and Lifehacks sections.

~ You'll see your genetic data in the articles and reports.

Join Here

Lifehacks:

Adjusting light at the right time:

Blue-blocking glasses at night help tremendously. Blocking the blue wavelengths at night increases melatonin production and resets the circadian clock to be in sync with the day/night light cycle.

There are now many options for blue-blocking glasses online and elsewhere — just make sure they block 100% of blue light. You don’t want the video gamer glasses that block only 30-40% of blue light for blocking light at night.

Member Content:

Why join Genetic Lifehacks?

~ Membership supports Genetic Lifehack's goal of explaining the latest health and genetics research.

~ It gives you access to the full article, including the Genotype and Lifehacks sections.

~ You'll see your genetic data in the articles and reports.

Join Here

Related Articles and Topics:

Is inflammation causing your depression or anxiety?

Over the past two decades, research shows a causal link between increased inflammatory markers and depression. Genetic variants in the inflammatory-related genes can increase the risk of depression and anxiety.

Tryptophan: Building Serotonin and Melatonin

Tryptophan is an amino acid that the body uses to make serotonin and melatonin. Genetic variants can impact the amount of tryptophan that is used for serotonin. This can influence mood, sleep, neurotransmitters, and immune response.

Blue Blocking Glasses

An easy way to improve sleep and increase melatonin production at night is to wear blue light blocking glasses before bed. Explore the research on why this is so important, and learn about the different options available for blue-blocking glasses.

BPIFB4 Gene Linked to Longevity and Heart Health

Discover the impact of the BPIFB4 gene on longevity and immunity, and find out if you have the longevity variant in your genotype report.