Key takeaways:

~ C15:0 is an odd-chain saturated fatty acid with many promising health benefits.

~ Higher levels of C15:0 are associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, a reduced risk of diabetes, and a reduced risk of obesity.

~ A clinical trial with supplemental C15 shows that it doesn’t promote weight loss but it may improve some liver health biomarkers.

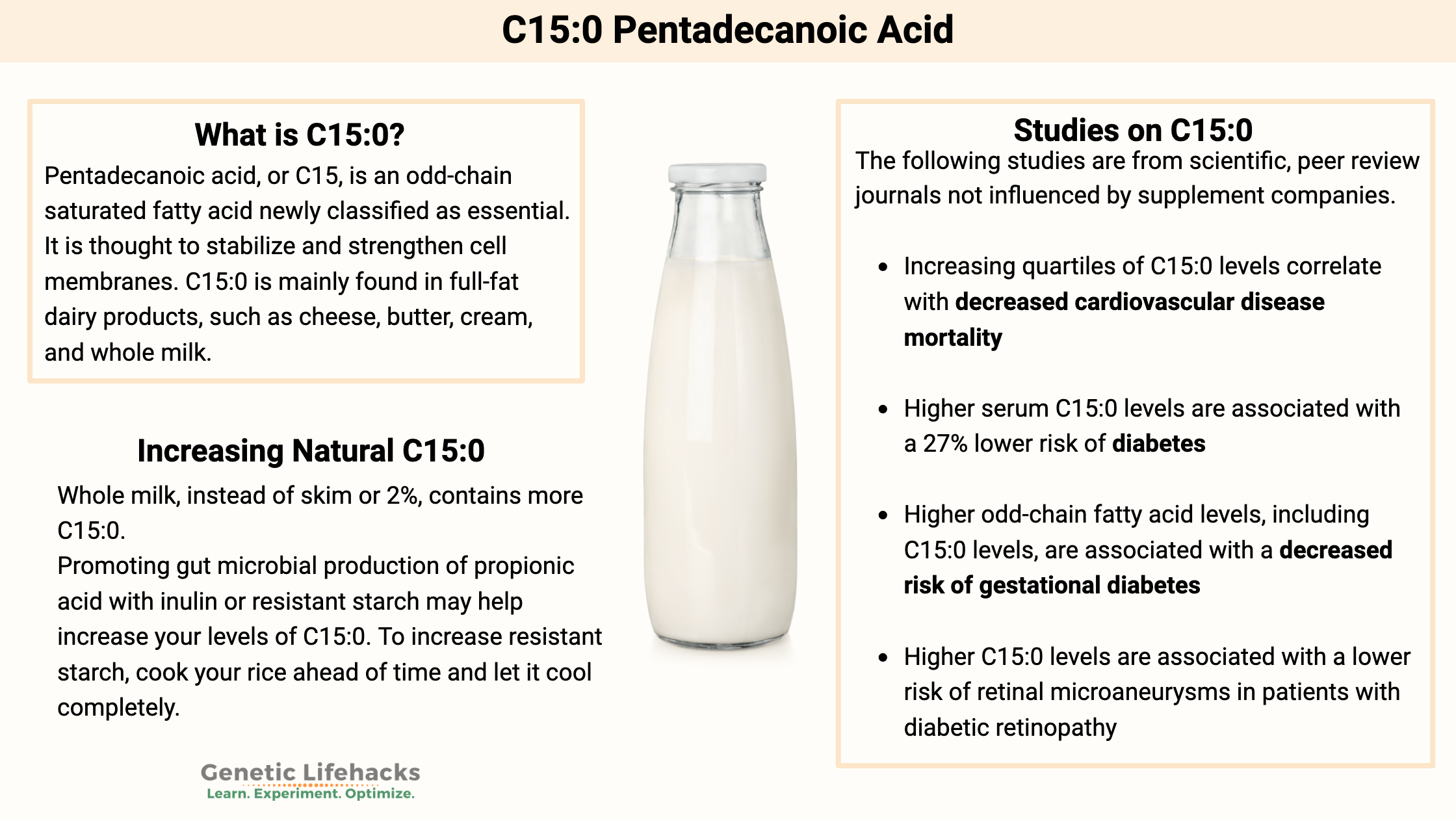

~ Promoting gut microbial production of propionic acid with inulin or resistant starch may help increase your levels of C15:0.

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

What is C15:0 or Fatty 15?

Pentadecanoic acid, or C15, is an odd-chain saturated fatty acid with studies linking it to decreased risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and overall mortality. It is referred to in studies as C15:0 and is sold in the US only under the brand name Fatty 15. The supplement manufacturer explains it supports “long-term health and wellness,” as well as strengthening cells and repairing mitochondrial function.

This article explores the research on pentadecanoic acid (C-15), looking at where it comes from, the results of animal studies and clinical trials, and how you can get more of it.

Avoiding bias:

There are a couple of hundred scientific articles published by the manufacturer of the C15:0 supplement that explore the benefits of pentadecanoic acid. I wanted to state up front that I’m focusing specifically on peer-reviewed studies that don’t seem to be funded by any supplement company – just to avoid any inadvertent biases.

Background on saturated fatty acids:

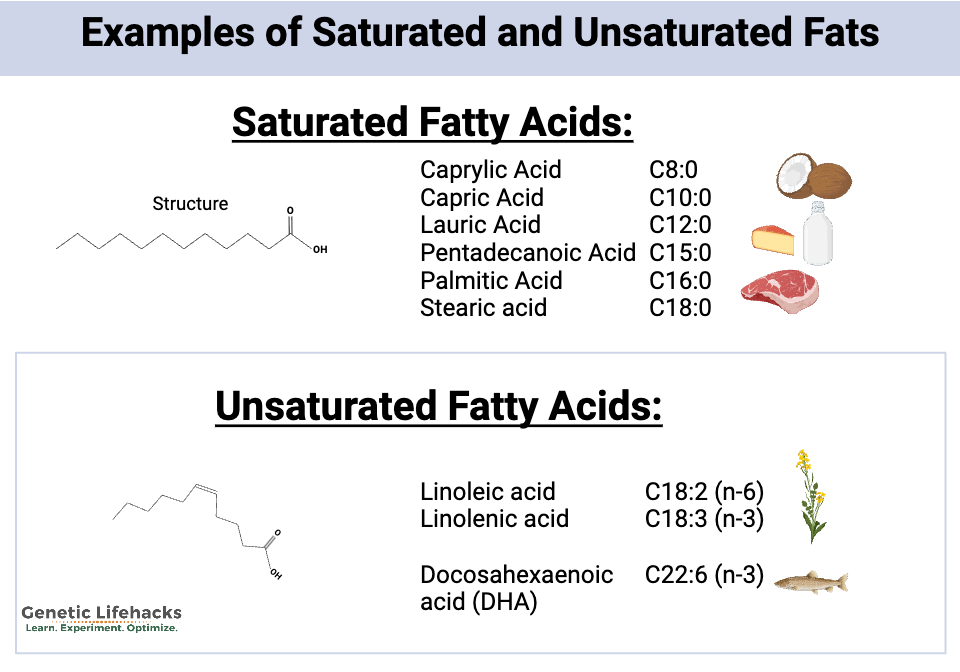

C15:0 is an odd-chain saturated fatty acid, which is unusual, so let’s start with a little background on saturated fats.

Saturated fats are chains of fatty acids with no double bonds, making them stiffer than polyunsaturated fats, which have some double bonds that allow them to bend. This makes butter (saturated fat) a solid at room temperature compared to olive oil (unsaturated fat).

Saturated fatty acids are used in the body in multiple ways – for energy, as part of the cell membrane, as precursors for inflammatory molecules, as signaling molecules, and as protein modifications.[ref]

Saturated fats are named and referenced by the number of carbon atoms. For example, palmitic acid is called C16:0. The number before the colon indicates the number of carbon atoms, and the number after the colon is the number of double bonds.

We get saturated fats from food, and we can make them in our cells through a process called fatty acid synthesis. Most of the saturated fats we eat and make in our bodies are even-chain fatty acids. However, we also have small amounts of odd-chain saturated fatty acids in our tissues and plasma. Odd-chain saturated fatty acids found in the body include pentadecanoic acid (C15:0) and heptadecanoic acid (C17:0).

The dietary emphasis on saturated versus unsaturated fats is an oversimplification that overlooks the functions of different fatty acids and the conversion between fatty acids. For example, the different saturated fats – from palmitic acid (C16:0) to the medium chain fatty acids in coconut oil (C8:0, C10:0, and C12:0) – all have different functions and uses in the body.

Odd-chain fatty acids and diet: Setting the stage

C15:0 is mainly found in full-fat dairy products like cheese, butter, cream, and whole milk.[ref] Decades ago, it was recommended to reduce saturated fat intake to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease. As a result, full-fat dairy products were demonized, and everyone switched to skim or 2% milk. Milk has about 1% of the fatty acids as C15:0, so switching to fat-free dairy reduces the C15:0 obtained from the diet. [ref]

Odd-chain fatty acids are also found in small amounts in lamb, beef, seal meat, and some fish species.[ref][ref] Tamarind kernel oil also contains small amounts of pentadeconoic acid, as do apple ciders, which have a sharp taste. Several essential oil compounds have also been identified as containing small amounts of pentadecanoic acid.[ref][ref][ref][ref]

| Food Source | C15:0 Content | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Full-fat dairy (milk, cheese, butter, cream) | ~1% of dairy fat | Main dietary source |

| Lamb, beef, seal meat | Small amounts | Secondary animal sources |

| Certain fish species | Small amounts | |

| Tamarind kernel oil | Trace | Rare plant source |

| Apple cider, essential oils | Trace | Minimal contribution |

We will come back to dietary changes that can increase C15:0 levels in just a bit…

Studies on C15:0 levels: Why this fatty acid is interesting!

The interest in odd-chain fatty acids stems from studies dating back several decades that show that higher levels of C15:0 and C17:0 are correlated with better health, including lower rates of diabetes, heart disease, and overall mortality.[ref][ref]

Here are just a few of the studies with positive associations with health:

- Higher dietary intake of odd-chain fatty acids was associated with a 36% lower risk of mortality over 11 years in a large study.[ref]

- Increasing quartiles of C15:0 levels correlate with decreased cardiovascular disease mortality in the Swedish population.[ref]

- Higher dietary C15:0 is associated with a 22% decreased risk of hypertension (US population).[ref]

- Higher serum C15:0 levels are associated with a 27% lower risk of diabetes.[ref]

- Higher odd-chain fatty acid levels, including C15:0 levels, are associated with a decreased risk of gestational diabetes.[ref]

- Higher C15:0 levels are associated with a lower risk of retinal microaneurysms in patients with diabetic retinopathy.[ref]

- Lower BMI level is associated with higher C15:0 levels.[ref] Although not all studies agree. A 2025 study showed that C17:0 was the driving force behind the benefits of odd-chain saturated fatty acids, and not C15:0.[ref]

There was one exception to the positive correlations… A recent study (Sept. 2024) of Chinese adults aged 45+ found that higher levels of C15:0 correlated with a 2-fold increased risk of mild cognitive impairment (MCI). All of the different even and odd chain saturated fatty acids were associated with an increased risk of MCI.[ref]

In addition, a recent (Sept. 2024) study of free fatty acid levels and mortality in the 3900 US did not find that C15:0 levels were statistically significant in mortality rates.[ref]

| Health Outcome | Association with Higher C15:0 | Reference Type |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular disease | Lower risk | Observational |

| Diabetes (type 2, gestational) | Lower risk | Observational |

| Obesity (lower BMI) | Lower risk | Observational |

| Liver health (NAFLD) | Improved biomarkers | Clinical/Animal |

| Cognitive impairment (MCI) | Higher risk (in one study) | Observational (China, 2024) |

| All-cause mortality | Lower risk | Observational |

For the most part, these observational studies show that C15:0 levels are higher in healthy people, but they don’t show causality. To know whether increasing C15:0 levels will increase longevity and healthspan, we need to look at clinical trials and animal studies.

Human clinical trials of supplemental C15:

Not a lot to see here…

There have only been two clinical trials of C15:0 supplements, and both showed minimal effect from the supplement.

Metabolic trial:

A 2024 clinical trial involving 30 overweight adults tested 200 mg/day of C15:0 vs. placebo. The clinical trial was partially funded by the Fatty 15 supplement manufacturer. The goal of the study was to detect increases in plasma C15:0 levels and to determine if there were beneficial effects related to weight and metabolic syndrome.

Half of the participants taking C15:0 had a significant increase in C15:0 levels, while half of the participants taking the supplement had no increase. (The placebo group also did not have an increase in C15.) The portion of participants who had a significant increase in C15:0 to over 5 μg/mL also showed a decrease in liver enzymes (ALT and AST), which could indicate improvement in fatty liver. Notably, participants did not lose weight or improve their blood pressure. They also didn’t have a decrease in cholesterol. No significant adverse events were found.[ref][ref]

C15:0 plus Mediterranean-style diet:

A study involving 88 women in China with NAFLD looked at the effect of diet (Asian-adapted Mediterranean-style diet), diet plus C15:0 supplement, or control (normal diet, no supplement).

The study found that the diet+C15:0 group lost an average of 4.0 kg in 12 weeks, while the diet-alone group lost 3.4 kg. The control group lost 1.5 kg. Liver fat tests showed that both the diet and the diet+C15:0 groups had a significant reduction in liver fat. The only difference that the C15:0 supplement added compared to diet alone was a further reduction in LDL cholesterol and an increase in Bifidobacterium adolescentis, a healthy bacterium found in the gut microbiome. The Mediterranean-style Asian diet included fresh vegetables and lots of dietary fiber.[ref]

Cell line and animal studies:

Studies in animals and human cells can show why higher C15:0 levels correlate with better health outcomes.

- Breast cancer: tamoxifen plus pentadeconoic acid

A cell study found that pentadeconoic acid combined with tamoxifen worked synergistically to suppress cancer stem cells. While this is very preliminary, the mechanism of action here is promising. Essentially, C15 reduces the proliferation of breast cancer stem cells, along with making them more susceptible to tamoxifen. Clinical trials are needed to understand dosage and in vivo effects. [ref][ref] - Fatty liver disease:

Studies in mice show that C15:0 deficiency is a contributing factor to liver injury in fatty liver disease.[ref] It has been known for a long while that non-alcoholic fatty liver disease can be reversed in mice by the addition of dietary fiber. A recent study showed that inulin (fiber) ameliorated fatty liver by increasing beneficial gut microbes, which in turn increased pentadecanoic acid. [ref] Dairy fat intake and C15:0 levels in children are also associated with lower NAFLD levels.[ref] - Glucose uptake:

A cell study showed that C15:0 increased glucose uptake by promoting the translocation of the GLLUT4 glucose receptor to the cell membrane. The study also showed that C15:0 had no effect on the insulin-dependent pathway involving the insulin receptor for moving glucose into cells. - Inflammatory Bowel Disease:

A mouse model of IBD showed that C15 supplementation reduced inflammation and helped to preserve gut barrier integrity.[ref] - Biofilm disruption:

Bacterial biofilms are a microbial community of bacteria and fungi that are embedded within a matrix they produce of extracellular polymeric substances. Pentadeconoic acid is similar to the quorum-sensing signals involved in the regulation of biofilm formation. Adding pentadecanoic acid disrupts the formation of biofilms and helps to dissolve them. This has specifically been shown to be effective for a C. albicans/K. pneumoniae dual-species biofilm.[ref]

Endogenous synthesis of C15:0: Making pentadecanoic acid

Endogenous synthesis means that C15:0 is made naturally in the body. Let’s take a look at the research studies that show how C15:0 is synthesized.

Note that the articles published by the supplement manufacturer claim that C15:0 is an essential fatty acid, meaning that endogenous production of C15:0 doesn’t happen (this is likely an important part of their patent).[ref]

Can we only get C15:0 from dairy products?

Many of the studies on C15:0 levels directly attribute the higher levels to consuming more full-fat dairy products, since that is the largest source of dietary C15:0. However, quite a few other studies show that the body can produce C15:0 endogenously and does not need to directly get it from dietary sources.

Three points make it unlikely that dietary milk consumption is required:

- The blood levels of odd-chain fatty acids are similar in vegans, vegetarians, and omnivores. This shouldn’t be the case if the main sources are dietary (milk, some fish, beef). In addition, many population groups worldwide do not traditionally consume milk.[ref]

- In humans, the C17:0 levels are found at a higher concentration than C15:0 (about a 2:1 ratio), which is the opposite of what is found in dairy products (1:2 ratio).[ref]

- Studies on people with rare genetic disorders involving propionic aciduria or methylmalonic aciduria show that when propionic acid is blocked from entering the citric acid cycle, it leads to high concentrations of C15:0 and C17:0.[ref][ref]

How do we synthesize C15:0 in the body?

There are two known routes of synthesis in the body: by gut bacteria in the colon, providing propionic acid, which is converted into C15:0 in the liver or by the conversion of other long-chain fatty acids into C15:0 in cells.

Gut microbiome, propionic acid from fiber, and conversion to C15:

The gut microbiome produces most of the short-chain fatty acids in the body. These short-chain fatty acids, such as propionic acid, are produced by fermentation of fiber in the gut microbiome. Propionic acid, or propionate, can then be converted into C15:0 in the liver.

Animal studies show that either increasing dietary fiber or supplementing with propionate (short-chain fatty acid) directly increases the odd-chain fatty acid levels. This indicates that the gut microbiome likely converts dietary fiber (e.g. inulin) to propionate, which is then taken up in the intestines and transported to the liver, which can convert it into C15:0.[ref][ref][ref]

Studies in people show the same results. A clinical trial looked at whether odd-chain fatty acid levels increase when supplementing with inulin (dietary fiber), propionate (short-chain fatty acid), or cellulose (control). Again, the gut microbiome produces propionate from fermenting dietary fiber. Seven days of supplementing with either inulin or propionate increased C15:0 levels by 13-17%. It also increased C17:0 levels. The control group had no increase in C15:0. Essentially, both inulin and propionate supplementation can increase C15:0 levels a little.[ref]

Conversion from other fatty acids:

While the elongation of propionic acid (short-chain saturated fat) into C15:0 or C17:0 is fairly well established, researchers also believe that there are two other ways that C15:0 can be synthesized in cells. A process called alpha-oxidation is thought to be involved.[ref] Research shows that very long-chain saturated fats (25:0 or 23:0) can be converted into C15:0 and C17:0, and vice versa. There’s also some evidence that the oxidation of cholesterol side chains during bile acid formation can lead to C15:0 formation.[ref]

The conversion of very long-chain saturated fats to C15:0 is believed to be minor in comparison to the formation of C15:0 from propionate.[ref]

Recap: How the Body Gets C15:0

~ Diet: Main source is full-fat dairy; small amounts in some meats and fish.

~ Endogenous synthesis: The body can make C15:0 from propionic acid (produced by gut bacteria fermenting dietary fiber) and, to a lesser extent, from very long-chain fatty acids.

~ Vegans and vegetarians: Similar blood levels of C15:0 as omnivores, suggesting dietary intake is not the only source, clearly showing endogenous synthesis.

Lifehacks: Maximizing your production of C15:0

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Conclusion:

The studies on higher C15:0 levels being found in people with better heart health and better metabolic health are interesting. However, the correlation could also be an indication that those people consume more fiber and have good gut health or that they consume more full-fat dairy products.

More research is needed – along with placebo-controlled clinical trials – to show why increasing C15:0 levels is important and whether it will move the needle on health or longevity.

~ While higher C15:0 levels are linked to better heart and metabolic health, causality is not established.

~ Supplementation shows some promise for liver health, but effects are modest.

~ Increasing dietary fiber and full-fat dairy are practical ways to support C15:0 levels.

~ More research is needed to clarify the health impact of intentionally raising C15:0.

Related articles and topics:

Lithium Orotate and Vitamin B12: Benefits for Mood and Cognitive Support

References: