Key takeaways:

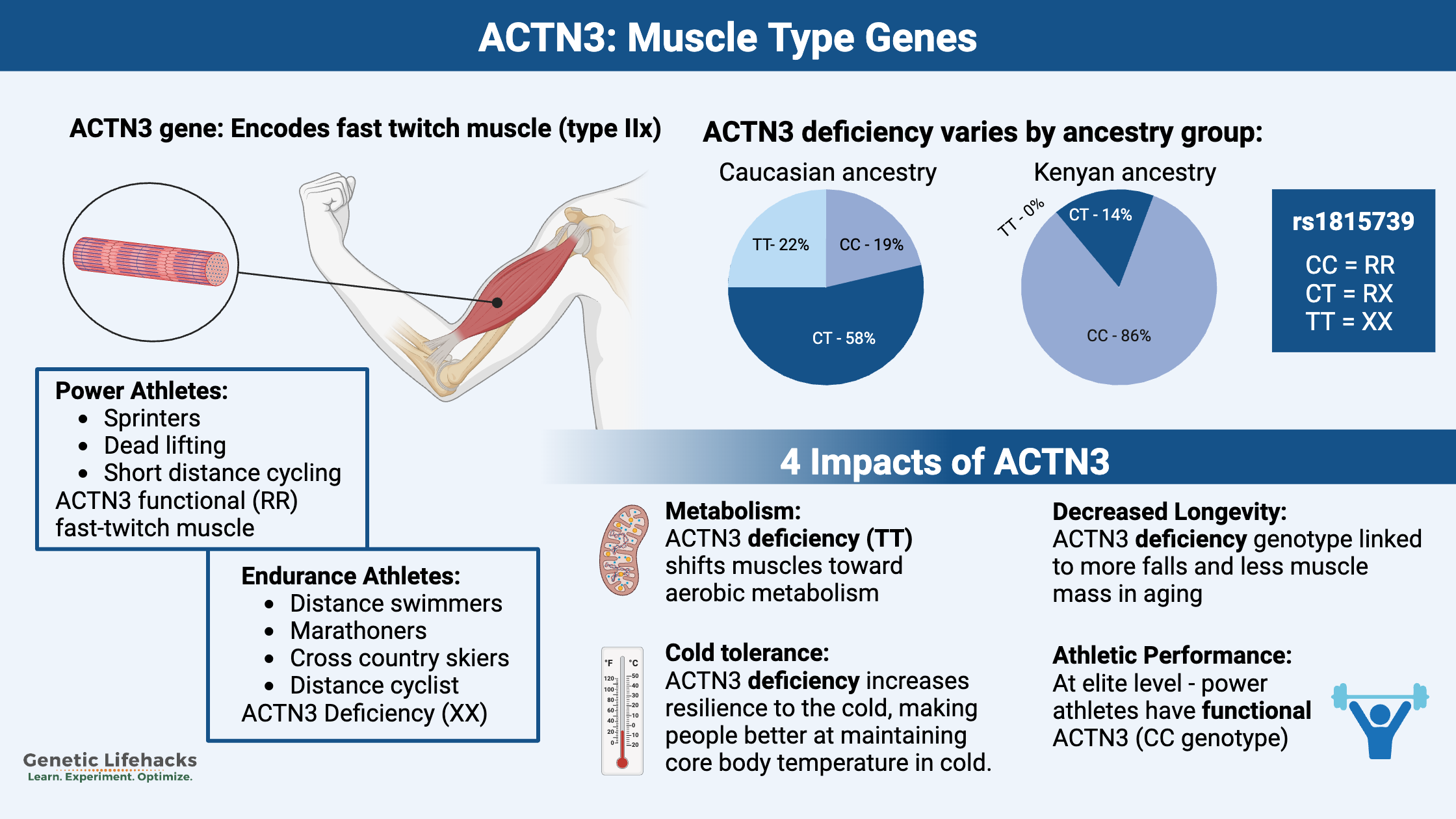

~ The ACTN3 gene encodes fast-twitch muscle fiber, but about 20% of the population has a non-functioning gene.

~ Non-functioning ACTN3 can affect athletic performance in certain types of sports.

~ Researchers think the ACTN3 gene variant is prevalent in certain ancestry groups due to adaptation to cold.

This article digs into the research on the ACTN3 gene, including research on athletic performance, cold adaptation, metabolic health, and aging. Don’t want to read the background studies? Jump ahead to check your genetic data for the ACTN3 gene.

Members will see their genotype report below, plus the natural solutions in the Lifehacks section. Join today.

What does the ACTN3 gene do?

The ACTN3 gene encodes the alpha actinin 3 protein found in fast-twitch muscles. Fast-twitch muscles are responsible for explosive bursts of power or speed.

A common genetic variant in the ACTN3 gene causes about 20% of the population not to produce fast-twitch skeletal muscle fibers.

First, let me give you a quick overview of how muscles work, and then I’ll go into the research studies specific to the ACTN3 protein.

Muscle fibers:

Skeletal muscles attach to your bones and help you move and stabilize your joints. In addition to movement, your skeletal muscles also stop movement, resist gravity, and other forces. They are constantly working, even when you are still.

Your skeletal muscles are made up of muscle fibers, blood vessels, nerve fibers, and connective tissue. The skeletal muscle fibers contain functional units called sarcomeres. Each sarcomere includes the filaments actin and myosin.

Actin forms the thinner strands of the sarcomere, and myosin forms the thicker strands.

Here’s a quick video on how actin and myosin work in the muscle:

Zooming in further, there are several types of actin proteins, one of which is coded for by the ACTN3 gene.

The ACTN3 (α actinin 3) protein is only found in fast-twitch muscle fibers. There is also an ACTN2 protein that is found in all muscle fibers.[ref]

One study explains: “The expression of α-actinin-3 protein is almost exclusively restricted to fast, glycolytic, type 2X fibers, which are responsible for producing ‘explosive’, powerful contraction”.[ref]

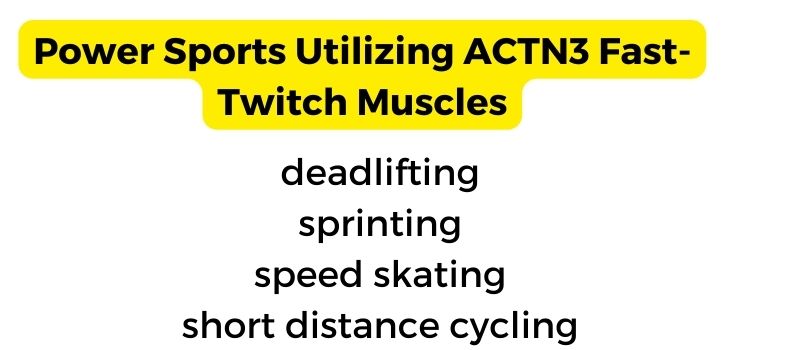

This type of explosive, powerful muscle contraction is needed in power sports such as:

What happens if you don’t have the ACTN3 protein?

Researchers created a mouse strain that lacks the ACTN3 gene to learn what happens with α actinin 3 deficiency.

They found that mice without the ACTN3 protein could run about 33% longer (similar to a long-distance runner). Most of the other parameters were the same for the mouse muscles, but the researchers did find the twitch half-relaxation time of the ACTN3-deficient muscles was 2.6 ms longer.[ref]

What about in people?

A fairly common genetic change in the ACTN3 gene causes some people not to produce the ACTN3 protein. This variant is referred to as R577X.

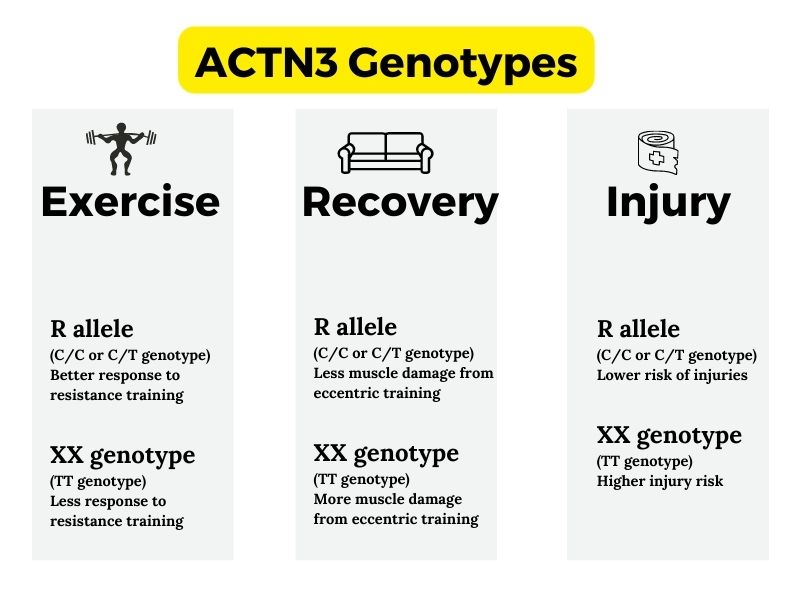

The R allele encodes the functioning ACTN3 protein, and the X allele is the non-functioning genotype.

The ACTN3 XX genotype in studies refers to people who have the non-functioning ACTN3 gene, which means they do not produce the ACTN3 protein. This correlates to ACTN3 rs1815739 TT and causes α actinin 3 deficiency.

The ACTN3 577 RR genotype means that you have two copies of the functioning ACTN3 gene (rs1815739 CC).

In between those two genotypes is rs1815739 CT.

More on what this all means, including how to check your genetic data in the Genotype Report below.

4 Impacts of ACT3:

Research on ACTN3 can be broken down into four categories:

- aerobic metabolism

- cold tolerance

- longevity and healthspan

- athletic performance

1) ACTN3 and metabolism:

Muscle tissue can function aerobically, burning glucose with plenty of oxygen, or function anaerobically, relying on lactic acid. Anaerobic respiration is quick and doesn’t need oxygen, but it also doesn’t produce as much ATP.

Discovered through mouse models and human testing, the ACTN3-deficient genotype shifts the muscles towards more aerobic metabolism, which may benefit endurance athletes.[ref]

2) Cold tolerance and adaptative advantage

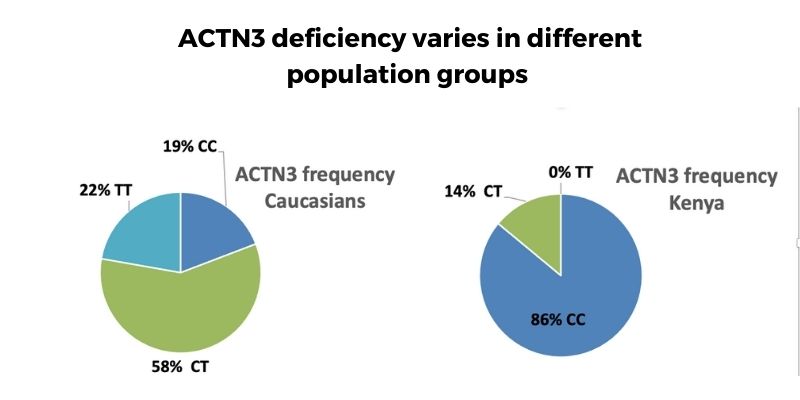

The frequency of the ACTN3-deficiency genotype varies by population group, with up to 25% of Caucasians being deficient compared to less than 1% of some African population groups.

While it seems that having the active ACTN3 gene would give an adaptive advantage for speed to our human ancestors, evolutionary biologists theorize that there must be a reason such a high percentage of some population groups carry the ACTN3 deficiency genotype.

The answer to this question may lie in cold adaptation. New research shows that as our human ancestors migrated north out of Africa and the Middle East, there was an increase in the percentage of people who were ACTN3 deficient.

Researchers recently showed that people with the ACTN3-deficient (TT) genotype are better at maintaining their core body temperature in the cold.[ref]

The study involved healthy young (18-40) males. The men were immersed in cold water to lower their core body temperature to 35.5°C – or for 120 minutes, whichever came first. The number of participants who maintained their core temperature above 35.5°C for 120 minutes of cold water immersion was calculated. Individuals with ACTN3-deficiency were twice as likely to complete the 120 minutes vs. people with ACTN3 intact (69% vs. 30%). The researchers also found that people with ACTN3-deficiency maintained body temperature without using up as much energy.[ref]

What is going on with the ACTN3 muscle type and cold? The researchers showed that the increased amount of slow-twitch muscle fiber increased heat production without shivering as much (and thus used less energy). While this is a nice advantage for adults in cold climates, it may be that the biggest driver of the mutation increasing in population groups is that it confers a survival advantage for infants in cold weather.

3) ACTN3 affects muscles, aging, and longevity:

As we age, we tend to lose muscle mass (starting around age 25!).

Studies show that ACTN3 deficiency is linked to lower lean muscle mass in aging. This, in turn, means that falls are more likely.

Three effects of ACTN3 non-functioning SNP:

- Elderly people with the ACTN3-deficient genotype may have more falls.[ref]

- Lean body mass is lower in older women with the ACTN3-deficient genotype.[ref]

- Older people who have the functional ACTN3 gene may have a (slight) advantage in maintaining muscle mass, which decreases the risk of falls.[ref]

Lower bone mineral density:

The ACTN3-deficiency genotype has links to lower bone mineral density (BMD) in postmenopausal women. The difference was about 1% lower BMD for women with the XX genotype.[ref]

Other studies have replicated this finding. The slightly lower muscle mass in people with the ACTN3-deficiency variant likely leads to less load-bearing activities daily.[ref]

Mouse studies show ACTN3 is expressed in osteoblasts (cells that form bone). ACTN3-deficiency could lead directly to slightly reduced bone mineral density.[ref]

4) Athletic performance and ACTN3:

Keep in mind that people with the ACTN3-functional genotype have more type IIx muscle fiber (fast-twitch glycolytic muscle).[ref]

Sprinter Gene: endurance vs. power

Large studies have investigated how the ACNT3 gene affects elite athletes:

- A big study published in 2003 found that no Olympic power athletes carried the ACTN3 deficient genotype. It was in stark comparison to the ~30% of Olympic endurance athletes carrying the ACTN3-deficient genotype.[ref]

- Studies back the idea that the ACTN3-deficient genotype is found much less often in elite power athletes (sprint athletes, weightlifters, etc.).[ref][ref][ref]

- Other results showed there was no significant difference in athletes when comparing the ACTN3 genotype.[ref][ref][ref] One study found the difference only existed for elite female athletes.[ref]

- Studies on elite athlete team sports (e.g., soccer) athletes have found that there is usually a normal population mix of ACTN3 genotypes.[ref][ref]

- A study found that athletes who produced ACTN3 had a much lower risk of acute ankle sprains.[ref]

ACTN3 and creatine kinase:

People with the ACTN3-deficient (XX) genotype had lower creatine kinase levels at baseline. Resting creatine kinase levels are usually higher in athletes and people with greater muscle mass.[ref] In fact, another study showed that people with the ACTN3-deficient genotype had 2% lower muscle mass on average. Not a huge difference, but it was statistically significant.[ref]

ACTN3 and rhabdomyolysis:

People with the ACTN3-deficiency polymorphism are ~ 3-fold more likely to have exertional rhabdomyolysis, which is a serious condition due to muscle break down. This death of muscle tissue causes the release of proteins into the bloodstream, negatively affecting the kidneys.[ref]

The In-betweeners – ACTN3 CT vs. CC:

While most studies don’t find a huge difference in people between having one copy of the deficiency allele (CT) compared to having two copies of the normal allele (CC), animal studies do show a minor difference. Using lab animals, researchers are better able to control the variables and see exactly what a gene variant may impact.

In this case, mice with one copy of the deficiency allele had endurance levels in between the mice with two copies of the functional ACTN3 gene and the mice with two copies of the ACTN3-deficiency genotype.[ref]

ACTN3 R577X Genotype Report:

🖨 Printable Overview (Members)

Check your genetic data for rs1815739 (23andMe v4, v5; AncestryDNA):

- C/C: functioning ACTN3, optimal for elite power athletes, more type IIx muscle fiber (RR)

- C/T: functioning ACTN3, optimal for elite power athletes (RX)

- T/T: non-functioning ACTN3 gene, more likely to be an endurance athlete than power athlete (XX)

Members: Your genotype for rs1815739 is —.

How common is the ACTN3 variant?

There are big differences in the prevalence of the ACTN3 variants based on ancestry. For example:

- About 25% of Caucasians have the ACTN3-deficient (TT) polymorphism.

- Less than 1% of some African population groups with the ACTN3-deficient genotype.[ref]

- Other population groups vary between those numbers, with a worldwide average of 18% of people carrying the ACTN3-deficient genotype.

Lifehacks for ACTN3:

Diet: What should you eat with the ACTN3 gene variant?

Mouse studies using a high-fat diet showed that the ACTN3-deficient genotype had less weight gain. However, human studies don’t show a significant effect on obesity from ACTN3 regarding diet.[ref]

ACTN3 Supplements:

A study of Brazilian runners looked at the interaction between the ACTN3 gene and pequi oil supplementation. Pequi oil is rich in carotenoids (provitamin A and lycopene – antioxidants) and consists mainly of palmitic and oleic fatty acids.

The researchers compared the athletes’ baseline metabolite measurements with the results after two weeks of supplemental pequi oil (400 mg/day). Creatine kinase, which normally rises after exercise, indicating muscle damage, was reduced after the antioxidant supplementation. The ACTN3-deficient athletes had significantly lower creatine kinase values after antioxidant supplementation than the athletes carrying the functional allele.[ref]

The pequi oil research indicates that antioxidant supplementation may be more effective for the ACTN-3 deficient genotype.

Bruxism (teeth grinding), ACTN3, and jaw muscles:

A recent study found that people who grind their teeth (bruxism) and also have the ACTN3 functional allele (CC) are likely to have larger jaw muscles than patients without the functioning ACTN3 (CT and TT). [ref]

Related article: Teeth grinding and your genes

Interaction between ACTN3 and ACE insertion/deletion SNP:

Related Articles and Topics:

Heat Shock Proteins: Cellular Resilience

Heat shock proteins are activated by cells in response to a stressful condition, such as exposure to high heat. Learn more about the essentials of heat shock proteins, including how to activate them and the genetic variants that impact how well they work.

TNF alpha: Higher inflammation

Your TNF genetic variants can impact your susceptibility to higher levels of inflammation.

BDNF supplements, genetics, and boosting cognitive function

The amount of brain-derived neurotrophic factor that you produce is partly due to genetics.

Athletic Performance Genes

If you are at the top of your sport and looking to optimize, genetics does come into play with muscle composition and endurance. Check out this article on other genetic variants that also impact athletic performance.

Sore Muscles – AMPD1 Deficiency

Do you end up getting sore after pretty much every workout at the gym? It could be that a deficiency caused by this AMPD1 genetic variant is the cause.

References:

Charbonneau, David E., et al. “ACE Genotype and the Muscle Hypertrophic and Strength Responses to Strength Training.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, vol. 40, no. 4, Apr. 2008, pp. 677–83. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318161eab9.

Clarkson, Priscilla M., Eric P. Hoffman, et al. “ACTN3 and MLCK Genotype Associations with Exertional Muscle Damage.” Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 99, no. 2, Aug. 2005, pp. 564–69. journals.physiology.org (Atypon), https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00130.2005.

Clarkson, Priscilla M., Joseph M. Devaney, et al. “ACTN3 Genotype Is Associated with Increases in Muscle Strength in Response to Resistance Training in Women.” Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 99, no. 1, July 2005, pp. 154–63. journals.physiology.org (Atypon), https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01139.2004.

Day, S. H., et al. “The Acute Effects of Exercise and Glucose Ingestion on Circulating Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme in Humans.” European Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 92, no. 4–5, Aug. 2004, pp. 579–83. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-004-1078-5.

Deuster, Patricia A., et al. “Genetic Polymorphisms Associated with Exertional Rhabdomyolysis.” European Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 113, no. 8, Aug. 2013, pp. 1997–2004. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-013-2622-y.

Döring, Frank E., et al. “ACTN3 R577X and Other Polymorphisms Are Not Associated with Elite Endurance Athlete Status in the Genathlete Study.” Journal of Sports Sciences, vol. 28, no. 12, Oct. 2010, pp. 1355–59. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2010.507675.

Druzhevskaya, Anastasiya M., et al. “Association of the ACTN3 R577X Polymorphism with Power Athlete Status in Russians.” European Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 103, no. 6, Aug. 2008, pp. 631–34. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-008-0763-1.

Erskine, R. M., et al. “The Individual and Combined Influence of ACE and ACTN3 Genotypes on Muscle Phenotypes before and after Strength Training.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, vol. 24, no. 4, Aug. 2014, pp. 642–48. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12055.

Frattini, Isabele Rissatto, et al. “ASSOCIAÇÃO DE POLIMORFISMOS GENÉTICOS DA ECA E DA ACTN3 COM CAPACIDADE FUNCIONAL E PREVALÊNCIA DE QUEDAS EM MULHERES NO FINAL DA IDADE ADULTA E INÍCIO DA TERCEIRA IDADE.” Journal of Physical Education, vol. 27, 2016. SciELO, https://doi.org/10.4025/jphyseduc.v27i1.2713.

Hogarth, Marshall W., et al. “Analysis of the ACTN3 Heterozygous Genotype Suggests That α-Actinin-3 Controls Sarcomeric Composition and Muscle Function in a Dose-Dependent Fashion.” Human Molecular Genetics, vol. 25, no. 5, Mar. 2016, pp. 866–77. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddv613.

Houweling, P. J., et al. “Exploring the Relationship between α-Actinin-3 Deficiency and Obesity in Mice and Humans.” International Journal of Obesity (2005), vol. 41, no. 7, July 2017, pp. 1154–57. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2017.72.

Koku, Fatma E., et al. “The Relationship between ACTN3 R577X Gene Polymorphism and Physical Performance in Amateur Soccer Players and Sedentary Individuals.” Biology of Sport, vol. 36, no. 1, Mar. 2019, pp. 9–16. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2018.78900.

Lucia, A., et al. “ACTN3 Genotype in Professional Endurance Cyclists.” International Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 27, no. 11, Nov. 2006, pp. 880–84. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2006-923862.

Ma, Fang, et al. “The Association of Sport Performance with ACE and ACTN3 Genetic Polymorphisms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” PloS One, vol. 8, no. 1, 2013, p. e54685. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0054685.

MacArthur, Daniel G., et al. “Loss of ACTN3 Gene Function Alters Mouse Muscle Metabolism and Shows Evidence of Positive Selection in Humans.” Nature Genetics, vol. 39, no. 10, Oct. 2007, pp. 1261–65. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng2122.

Massidda, Myosotis, et al. “ACTN3 R577X Polymorphism Is Not Associated with Team Sport Athletic Status in Italians.” Sports Medicine – Open, vol. 1, no. 1, Dec. 2015, p. 6. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-015-0008-x.

Moran, Colin N., et al. “Association Analysis of the ACTN3 R577X Polymorphism and Complex Quantitative Body Composition and Performance Phenotypes in Adolescent Greeks.” European Journal of Human Genetics: EJHG, vol. 15, no. 1, Jan. 2007, pp. 88–93. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201724.

Orysiak, Joanna, et al. “Individual and Combined Influence of ACE and ACTN3 Genes on Muscle Phenotypes in Polish Athletes.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 32, no. 10, Oct. 2018, pp. 2776–82. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001839.

Papadimitriou, I. D., et al. “The ACTN3 Gene in Elite Greek Track and Field Athletes.” International Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 29, no. 4, Apr. 2008, pp. 352–55. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-965339.

Papadimitriou, Ioannis D., et al. “ACTN3 R577X and ACE I/D Gene Variants Influence Performance in Elite Sprinters: A Multi-Cohort Study.” BMC Genomics, vol. 17, Apr. 2016, p. 285. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-016-2462-3.

Pickering, Craig, and John Kiely. “ACTN3, Morbidity, and Healthy Aging.” Frontiers in Genetics, vol. 9, Jan. 2018, p. 15. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2018.00015.

—. “ACTN3, Morbidity, and Healthy Aging.” Frontiers in Genetics, vol. 9, Jan. 2018, p. 15. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2018.00015.

Ribeiro, Ieler Ferreira, et al. “The Influence of Erythropoietin (EPO T → G) and α-Actinin-3 (ACTN3 R577X) Polymorphisms on Runners’ Responses to the Dietary Ingestion of Antioxidant Supplementation Based on Pequi Oil ( Caryocar Brasiliense Camb.): A before-after Study.” Journal of Nutrigenetics and Nutrigenomics, vol. 6, no. 6, 2013, pp. 283–304. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1159/000357947.

Saunders, C. J., et al. “No Association of the ACTN3 Gene R577X Polymorphism with Endurance Performance in Ironman Triathlons.” Annals of Human Genetics, vol. 71, no. Pt 6, Nov. 2007, pp. 777–81. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1809.2006.00385.x.

Schüler, Rita, et al. “High-Saturated-Fat Diet Increases Circulating Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme, Which Is Enhanced by the Rs4343 Polymorphism Defining Persons at Risk of Nutrient-Dependent Increases of Blood Pressure.” Journal of the American Heart Association, vol. 6, no. 1, Jan. 2017, p. e004465. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.004465.

Shang, X., et al. “Association between the ACTN3 R577X Polymorphism and Female Endurance Athletes in China.” International Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 31, no. 12, Dec. 2010, pp. 913–16. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1265176.

Shang, Xuya, et al. “The Association between the ACTN3 R577X Polymorphism and Noncontact Acute Ankle Sprains.” Journal of Sports Sciences, vol. 33, no. 17, 2015, pp. 1775–79. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2015.1012098.

Vincent, Barbara, et al. “ACTN3 (R577X) Genotype Is Associated with Fiber Type Distribution.” Physiological Genomics, vol. 32, no. 1, Dec. 2007, pp. 58–63. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1152/physiolgenomics.00173.2007.

Walsh, Sean, et al. “ACTN3 Genotype Is Associated with Muscle Phenotypes in Women across the Adult Age Span.” Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md.: 1985), vol. 105, no. 5, Nov. 2008, pp. 1486–91. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.90856.2008.

Wyckelsma, Victoria L., et al. “Loss of α-Actinin-3 during Human Evolution Provides Superior Cold Resilience and Muscle Heat Generation.” The American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 108, no. 3, Mar. 2021, pp. 446–57. www.cell.com, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.01.013.

Yang, Nan, Daniel G. MacArthur, et al. “ACTN3 Genotype Is Associated with Human Elite Athletic Performance.” American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 73, no. 3, Sept. 2003, pp. 627–31.

—. “ACTN3 Genotype Is Associated with Human Elite Athletic Performance.” American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 73, no. 3, Sept. 2003, pp. 627–31.

—. “ACTN3 Genotype Is Associated with Human Elite Athletic Performance.” American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 73, no. 3, Sept. 2003, pp. 627–31.

Yang, Nan, Aaron Schindeler, et al. “α-Actinin-3 Deficiency Is Associated with Reduced Bone Mass in Human and Mouse.” Bone, vol. 49, no. 4, Oct. 2011, pp. 790–98. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2011.07.009.

—. “α-Actinin-3 Deficiency Is Associated with Reduced Bone Mass in Human and Mouse.” Bone, vol. 49, no. 4, Oct. 2011, pp. 790–98. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2011.07.009.