Key takeaways:

~ An FUT2 gene variant controls whether or not you secrete your blood type into your saliva and other bodily fluids, such as your intestinal mucosa. This is referred to as your secretor status for being a ‘secretor’ or ‘non-secretor’.

~ Whether or not you secrete your blood type plays a big role in the type of bacteria in your gut microbiome. It also impacts your susceptibility to the norovirus.

~ Your genetic raw data can tell you whether you are a secretor or non-secretor.

~ Supplements may help with certain aspects of being a non-secretor.

Members will see their genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

Non-secretors, the FUT2 gene, and health symptoms:

First, let me explain a little bit of the background science on being a secretor or non-secretor of your blood type, and then I’ll explain how to check your 23andMe or AncestryDNA raw data for your secretor status.

Oligosaccharides and Blood Type:

Your blood type – type A, B, AB, or O – refers to the oligosaccharides that are present on your red blood cells. Oligosaccharides are carbohydrates consisting of three to nine monosaccharides (simple sugars). You may be familiar with oligosaccharides as prebiotics in supplements or foods like chicory and Jerusalem artichokes.

Your body also makes oligosaccharides, and one of those oligosaccharides is what makes up your ABO blood type. You’re likely familiar with blood types, such as type A positive or type O negative. The A, B, AB, and O refer to the type of oligosaccharide found on your red blood cells and in secretions such as saliva, tears, and the mucosa lining your intestines.

Interestingly, about 20% of people don’t secrete their blood type. And this creates some fascinating differences.

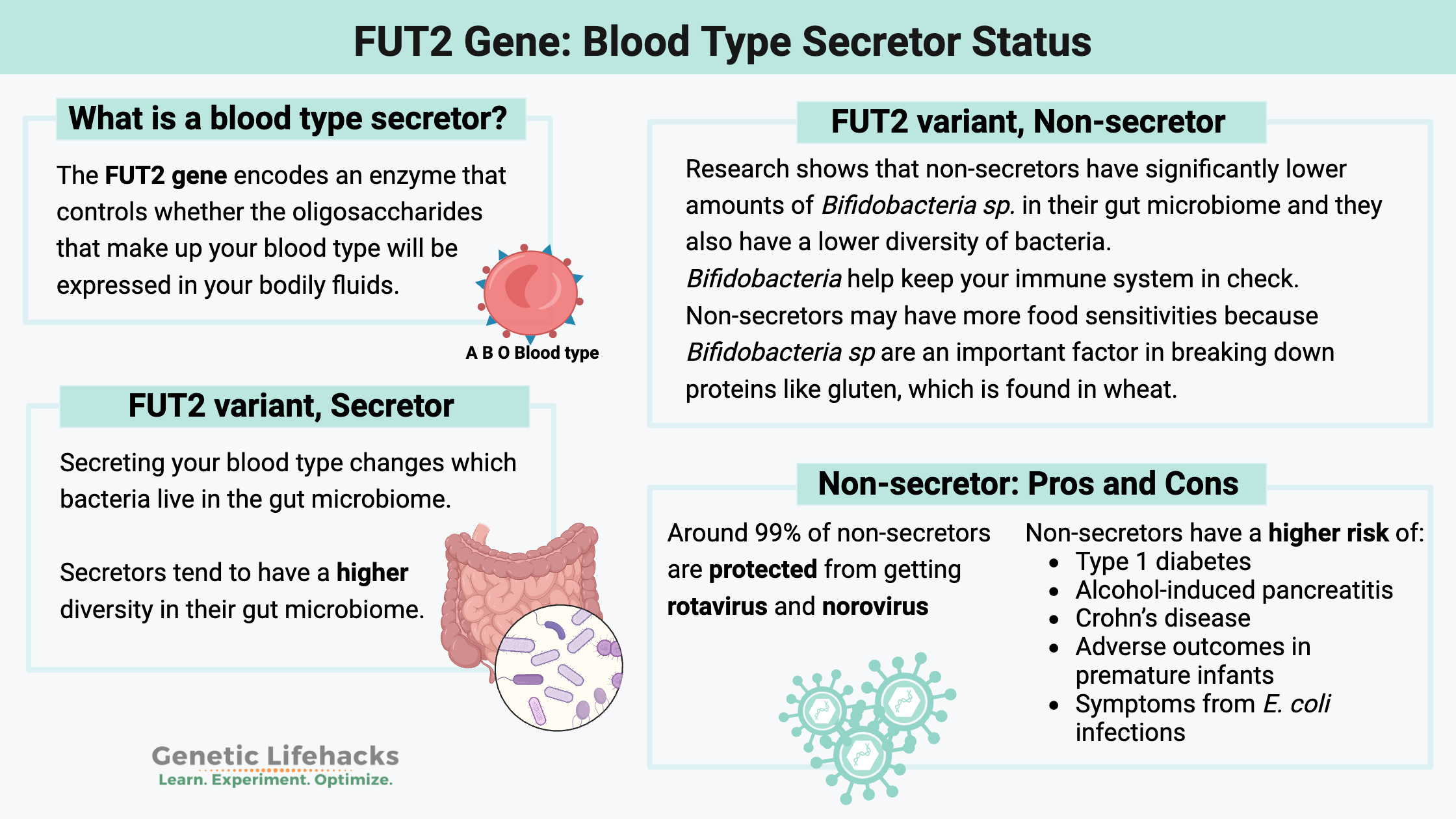

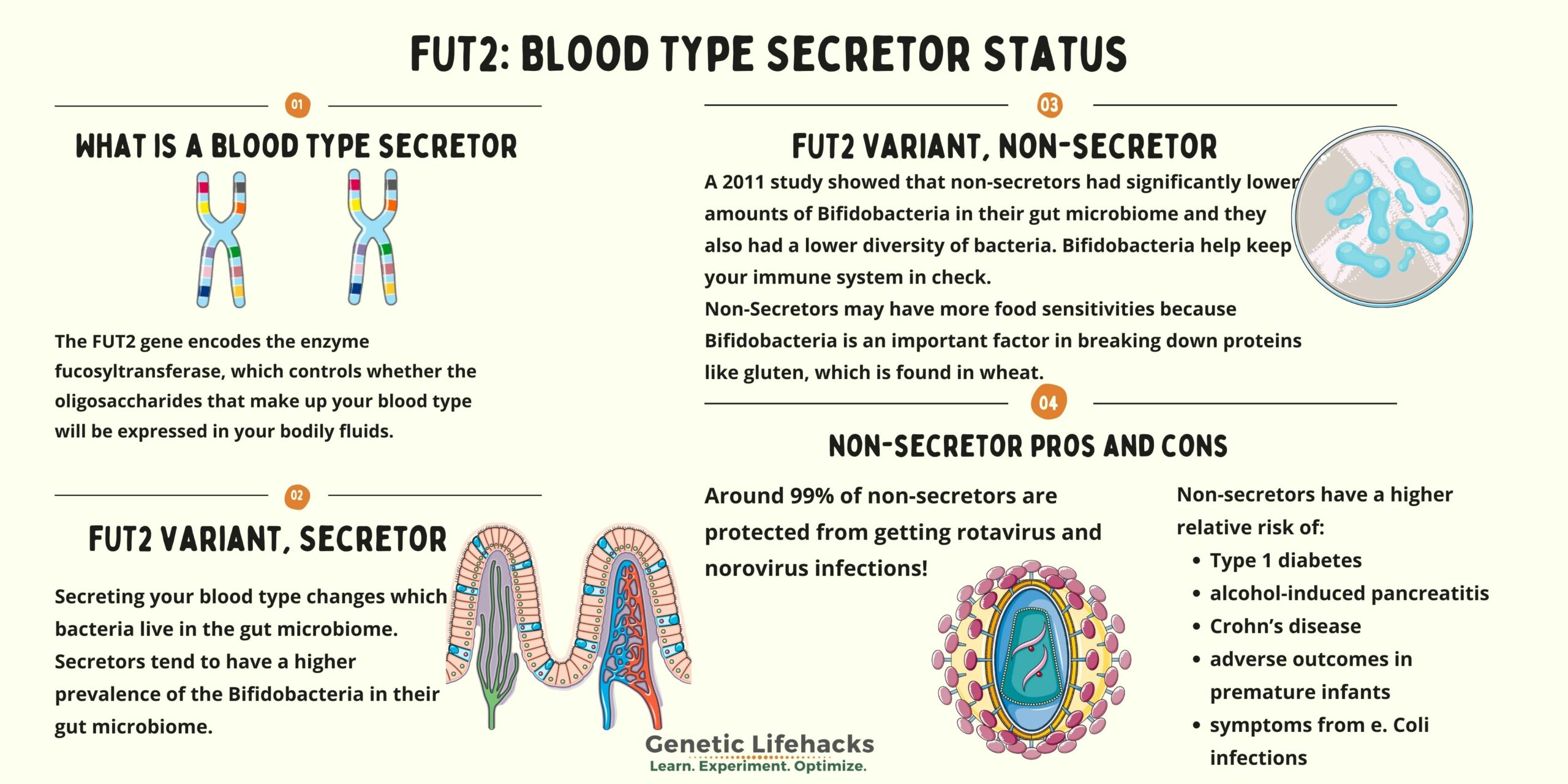

What is a blood type secretor?

The FUT2 gene encodes the enzyme fucosyltransferase, which controls whether the oligosaccharides that make up your blood type will be expressed in your bodily fluids (other than your blood).

For most people, the oligosaccharides that indicate your blood type are also found in your bodily fluids, including:

- intestinal mucosa

- sweat

- saliva

- tears

- vaginal mucosa

- semen

However, not everyone secretes their blood type in bodily fluids. About 20% of Caucasian and African populations are non-secretors of their blood type.

Why is this important? Being a non-secretor affects how your body interacts with bacteria inside you and impacts your response to certain viruses. Your gut microbiome continually interacts with your immune system, and the species of bacteria present can have an impact on your digestion and also on your immune response.

Let’s dig into some specifics on what is going on with the gut microbiome of non-secretors.

Bifidobacteria, gut microbiome, and secretors:

Researchers consider Bifidobacteria species to be one of the good guys when it comes to your gut microbiome. They are lactic and acetic acid-producing bacteria that help keep your immune system in check.

Bifidobacteria break down carbohydrates (specifically oligosaccharides) from the foods you eat. They also chow down on the oligosaccharides produced by our body in the intestinal mucosa. Your intestinal mucosa is what lines your intestines. It keeps your gut microbiome in the right place and away from your cells.

That’s where secreting your blood type (an oligosaccharide) comes into play.

Secretors tend to have a higher prevalence of the Bifidobacteria good guys in their gut microbiome.[ref][ref]

In fact, some studies show non-secretors have either low or no Bifidobacteria in their gut microbiome. Other studies show that there is decreased Bifidobacteria species diversity in non-secretors.[ref][ref]

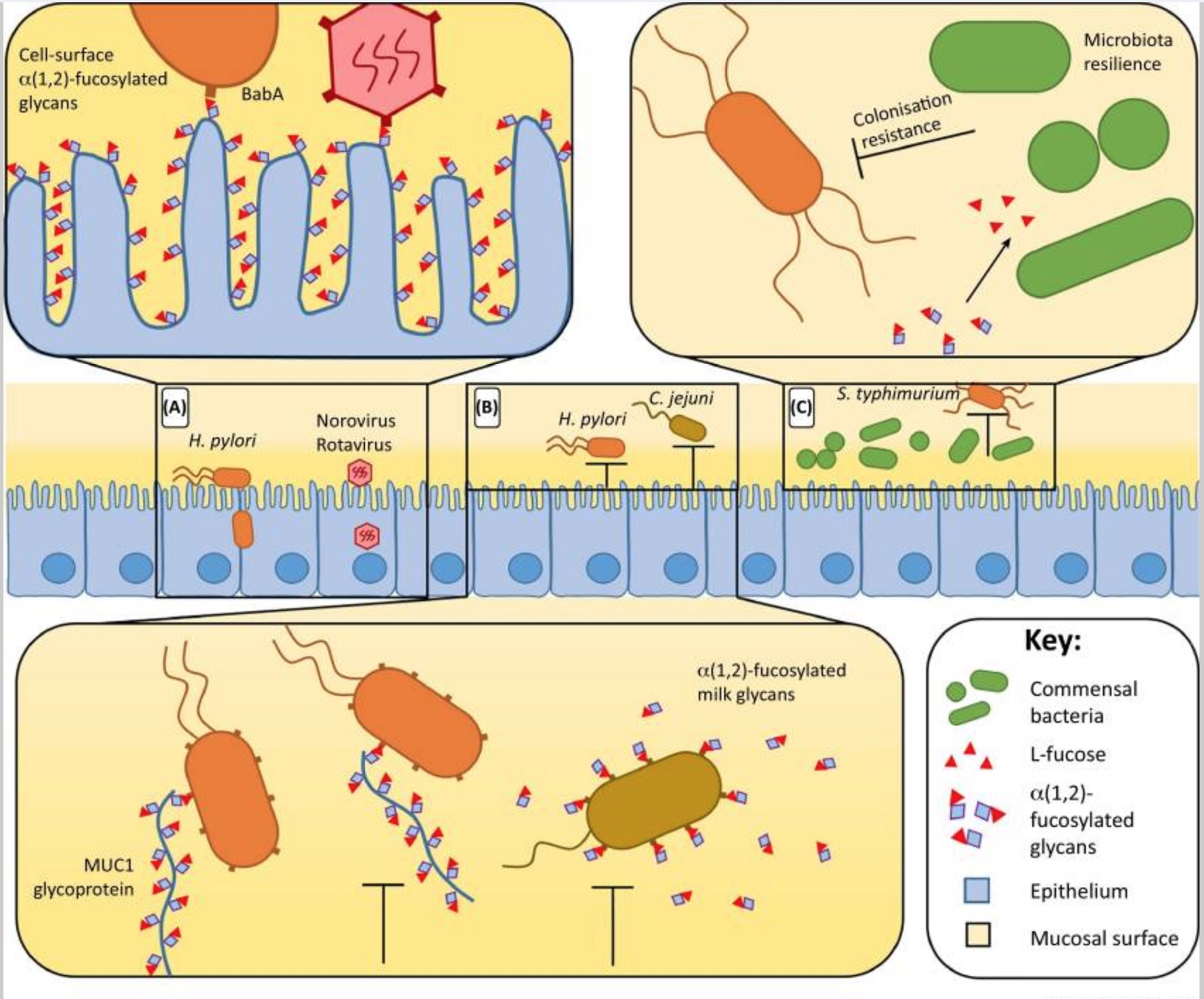

Pathogenic bacteria can’t get a grip:

There is one big advantage to being a non-secretor of your blood type — and it is likely that this advantage keeps the non-secretor phenotype so prevalent in the human population.

Certain viruses, such as norovirus, use the blood group glycans to attach to cells and enter them for infection. Without the blood group glycans in the intestinal mucosa, the viruses cannot attach to the intestinal cell walls and enter the body.

Thus, non-secretors are very unlikely to get sick from certain intestinal viruses such as Norovirus and Rotavirus (stomach flu). It is a superpower that likely kept your ancestors from dying from diarrheal disease.[ref][ref]

Non-secretors: Gut microbiome, nutrition, norovirus, B12

So what’s the big deal about being a non-secretor? Well, a lot of it comes back to our body’s interactions with the microbiome.

Non-secretor gut microbiome:

Lack of Bifidobacteria:

A 2011 study showed that non-secretors had significantly lower amounts of bifidobacteria in their gut microbiome. This makes sense because bifidobacteria are fed, in part, by the oligosaccharides in the intestinal mucosa. The same study showed that non-secretors also had a lower diversity of bacteria.[ref]

Another study in 2014 confirmed the findings regarding low bifidobacteria in non-secretor gut microbiomes. Additionally, non-secretors had lower species richness than the secretors.[ref]

Food sensitivities for non-secretors:

Why is the gut microbiome interaction so important? Bifidobacteria are good guys to have in the gut microbiome. They also may play a role in whether you have food sensitivities. Bifidobacteria help with the digestion of gluten, so a wheat or gluten sensitivity in someone who is a non-secretor may be related to the gut microbiome changes.

A plus for non-secretors: resistance to the norovirus!

Non-secretor status plays a role in infectious diseases as well. One big advantage of being a non-secretor is resistance to some viruses which cause what is commonly called the ‘stomach flu’.

- The norovirus and the rotavirus are much, much less likely to infect a non-secretor. Around 99% of non-secretors are protected from getting these infections![ref][ref]

- Infants who are non-secretors are significantly less likely to have symptomatic rotavirus and are less likely (but not completely protected) to be asymptomatic carriers of the rotavirus.[ref]

- Children who are non-secretors are less likely to have diarrheal diseases. Some research indicates that just carrying one copy of the non-secretor allele can reduce the risk of diarrheal diseases in children.[ref]

- H. pylori colonization is lower in non-secretors.[ref] H. pylori is a bacteria that resides in the stomach and can cause ulcers and stomach cancers.

Non-secretors are at an increased risk for certain diseases:

Secretor status also plays a role in non-infectious diseases, possibly through interactions with the gut microbiome. Non-secretors have a higher relative risk of:

- Type 1 diabetes[ref],

- alcohol-induced pancreatitis[ref],

- Crohn’s disease[ref][ref]

- adverse outcomes in premature infants[ref]

- symptoms from E. coli infections[ref]

- slightly higher risk of the mumps[ref]

- increase risk of middle ear infections[ref]

Keep in mind the increase in risk is simply a statistical connection with relative risk. Being a non-secretor does not necessarily mean you will get any chronic disease.

Vitamin B12 levels in non-secretors:

Non-secretors also often have higher serum vitamin B12 levels when they get their levels tested.

Importantly, this may not truly reflect the amount of B12 being transported into the cells. It could be that you have higher serum B12 because it is not getting into the cells. A methylmalonic acid (MMA) test may give you a better indication of your actual vitamin B12 status.[ref]

Breast milk: Oligosaccharides and FUT2 non-secretors

Your microbiome begins to develop at birth. An infant’s microbiome is mostly colonized by its mother, and bifidobacteria usually make up a large part of an infant’s microbiome.

Breast milk contains oligosaccharides that feed the baby’s microbiome. Non-secretor mothers do not produce the 2′-FL oligosaccharide in their breast milk, thus possibly impacting the baby’s microbiome.[ref]

Interestingly, babies born via C-section to non-secretor mothers have altered microbiomes.[ref] Not only did they not get exposure to the vaginal microbiome during birth, but they also aren’t receiving the secretor oligosaccharides from breast milk.

The effects on non-secretor status can also influence breastfed babies of non-secretor mothers, even when not born by C-section.

A 2015 study found that “Infants fed by non-secretor mothers are delayed in the establishment of a bifidobacteria-laden microbiota. This delay may be due to difficulties in the infant acquiring a species of bifidobacteria able to consume the specific milk oligosaccharides delivered by the mother.”[ref]

In other words, if your mom is a non-secretor, your gut microbiome may be altered a little bit.

Related article: Leveraging your gut microbiome to change your gene expression

FUT2: Secretor Genotype Report

Lifehacks: Supplements and foods for Non-secretors

If you are a non-secretor, you may want to minimize the ‘downside’ of the altered microbiome while enjoying the fact that you are unlikely to get the norovirus.

Probiotics containing Bifidobacteria:

Graphical Overview:

Related Articles and Topics

Genetic reasons why Low FODMAPs isn’t working for you (SI Gene)

While FODMAPs works for a lot of people with IBS, it doesn’t work for everyone. Genetic research explains why some people need a different dietary approach of IBS.

Debunking the blood type diet

Reviewing the current research studies on the blood type diet, which show that there is a lot of doubt around whether you can base your diet on your blood type.

Problems with IBS? Personalized solutions based on your genes

There are multiple causes of IBS, and genetics can play a role in IBS symptoms. Pinpointing your cause can help you to figure out your solution.

Fatty Liver: Genetic variants that increase the risk of NAFLD

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is now the leading cause of liver problems worldwide, bypassing alcoholic liver disease. It is estimated that almost half of the population in the US has NAFLD caused by a combination of genetic susceptibility, diet, and lifestyle factors.

References:

Aghdassi, Ali A., et al. “Genetic Susceptibility Factors for Alcohol-Induced Chronic Pancreatitis.” Pancreatology: Official Journal of the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP) … [et Al.], vol. 15, no. 4 Suppl, July 2015, pp. S23-31. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pan.2015.05.476.

Azad, Meghan B., et al. “FUT2 Secretor Genotype and Susceptibility to Infections and Chronic Conditions in the ALSPAC Cohort.” Wellcome Open Research, vol. 3, Sept. 2018, p. 65. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14636.2.

Bai, Yaqiang, et al. “Fucosylated Human Milk Oligosaccharides and N-Glycans in the Milk of Chinese Mothers Regulate the Gut Microbiome of Their Breast-Fed Infants during Different Lactation Stages.” MSystems, vol. 3, no. 6, Dec. 2018, pp. e00206-18. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1128/mSystems.00206-18.

Bunesova, Vera, et al. “Fucosyllactose and L-Fucose Utilization of Infant Bifidobacterium Longum and Bifidobacterium Kashiwanohense.” BMC Microbiology, vol. 16, no. 1, Oct. 2016, p. 248. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-016-0867-4.

Bustamante, Mariona, et al. “A Genome-Wide Association Meta-Analysis of Diarrhoeal Disease in Young Children Identifies FUT2 Locus and Provides Plausible Biological Pathways.” Human Molecular Genetics, vol. 25, no. 18, Sept. 2016, pp. 4127–42. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddw264.

Graziano, Vincent R., et al. “Norovirus Attachment and Entry.” Viruses, vol. 11, no. 6, May 2019, p. 495. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/v11060495.

Günaydın, Gökçe, et al. “Association of Elevated Rotavirus-Specific Antibody Titers with HBGA Secretor Status in Swedish Individuals: The FUT2 Gene as a Putative Susceptibility Determinant for Infection.” Virus Research, vol. 211, Jan. 2016, pp. 64–68. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2015.10.005.

Ihara, K., et al. “FUT2 Non-Secretor Status Is Associated with Type 1 Diabetes Susceptibility in Japanese Children.” Diabetic Medicine: A Journal of the British Diabetic Association, vol. 34, no. 4, Apr. 2017, pp. 586–89. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.13288.

Korpela, Katri, et al. “Fucosylated Oligosaccharides in Mother’s Milk Alleviate the Effects of Caesarean Birth on Infant Gut Microbiota.” Scientific Reports, vol. 8, Sept. 2018, p. 13757. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32037-6.

Kudo, T., et al. “Molecular Genetic Analysis of the Human Lewis Histo-Blood Group System. II. Secretor Gene Inactivation by a Novel Single Missense Mutation A385T in Japanese Nonsecretor Individuals.” The Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 271, no. 16, Apr. 1996, pp. 9830–37. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.271.16.9830.

Leccioli, Valentina, et al. “A New Proposal for the Pathogenic Mechanism of Non-Coeliac/Non-Allergic Gluten/Wheat Sensitivity: Piecing Together the Puzzle of Recent Scientific Evidence.” Nutrients, vol. 9, no. 11, Nov. 2017, p. 1203. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9111203.

Lewis, Zachery T., et al. “Maternal Fucosyltransferase 2 Status Affects the Gut Bifidobacterial Communities of Breastfed Infants.” Microbiome, vol. 3, 2015, p. 13. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-015-0071-z.

Magalhães, Ana, et al. “Muc5ac Gastric Mucin Glycosylation Is Shaped by FUT2 Activity and Functionally Impacts Helicobacter Pylori Binding.” Scientific Reports, vol. 6, May 2016, p. 25575. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25575.

Mankelow, Tosti J., et al. “Blood Group Type A Secretors Are Associated with a Higher Risk of COVID‐19 Cardiovascular Disease Complications.” Ejhaem, vol. 2, no. 2, May 2021, p. 175. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1002/jha2.180.

Mills, Susan, et al. “Precision Nutrition and the Microbiome Part II: Potential Opportunities and Pathways to Commercialisation.” Nutrients, vol. 11, no. 7, June 2019, p. 1468. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11071468.

Morrow, Ardythe L., et al. “Fucosyltransferase 2 Non-Secretor and Low Secretor Status Predicts Severe Outcomes in Premature Infants.” The Journal of Pediatrics, vol. 158, no. 5, May 2011, pp. 745–51. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.10.043.

Mottram, Lynda, et al. “FUT2 Non-Secretor Status Is Associated with Altered Susceptibility to Symptomatic Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli Infection in Bangladeshis.” Scientific Reports, vol. 7, Sept. 2017, p. 10649. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10854-5.

Rivière, Audrey, et al. “Bifidobacteria and Butyrate-Producing Colon Bacteria: Importance and Strategies for Their Stimulation in the Human Gut.” Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 7, June 2016, p. 979. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00979.

Ruas-Madiedo, Patricia, et al. “Mucin Degradation by Bifidobacterium Strains Isolated from the Human Intestinal Microbiota.” Applied and Environmental Microbiology, vol. 74, no. 6, Mar. 2008, pp. 1936–40. journals.asm.org (Atypon), https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02509-07.

Taylor, Steven L., et al. “Infection’s Sweet Tooth: How Glycans Mediate Infection and Disease Susceptibility.” Trends in Microbiology, vol. 26, no. 2, Feb. 2018, p. 92. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2017.09.011.

Tong, Maomeng, et al. “Reprograming of Gut Microbiome Energy Metabolism by the FUT2 Crohn’s Disease Risk Polymorphism.” The ISME Journal, vol. 8, no. 11, Nov. 2014, pp. 2193–206. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.64.

Tu, Li-Tzu, et al. “Genetic Susceptibility to Norovirus GII.4 Sydney Strain Infections in Taiwanese Children.” The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, vol. 36, no. 4, Apr. 2017, pp. 353–57. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000001446.

Velkova, Aneliya, et al. “The FUT2 Secretor Variant p.Trp154Ter Influences Serum Vitamin B12 Concentration via Holo-Haptocorrin, but Not Holo-Transcobalamin, and Is Associated with Haptocorrin Glycosylation.” Human Molecular Genetics, vol. 26, no. 24, Dec. 2017, pp. 4975–88. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddx369.

Wacklin, Pirjo, Jarno Tuimala, et al. “Faecal Microbiota Composition in Adults Is Associated with the FUT2 Gene Determining the Secretor Status.” PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 4, Apr. 2014, p. e94863. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094863.

Wacklin, Pirjo, Harri Mäkivuokko, et al. “Secretor Genotype (FUT2 Gene) Is Strongly Associated with the Composition of Bifidobacteria in the Human Intestine.” PLOS ONE, vol. 6, no. 5, May 2011, p. e20113. PLoS Journals, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020113.

Ye, Byong Duk, et al. “Association of FUT2 and ABO with Crohn’s Disease in Koreans.” Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, vol. 35, no. 1, Jan. 2020, pp. 104–09. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.14766.

Zhou, Feng, et al. “Association of Fucosyltransferase 2 Gene Variant with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Meta-Analysis.” Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research, vol. 25, Jan. 2019, pp. 184–92. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.911857.