Key takeaways:

~ Zinc is an important cofactor in many cellular processes.

~ Low zinc can impact immune health, impair wound healing, cause skin issues, and increase the risk of type 2 diabetes.

~ Genetic variants impact how zinc is transported into your cells. SNPs that reduce zinc transport may mean that you need to include more zinc in your diet to avoid deficiency.

Zinc, genetics, and your health:

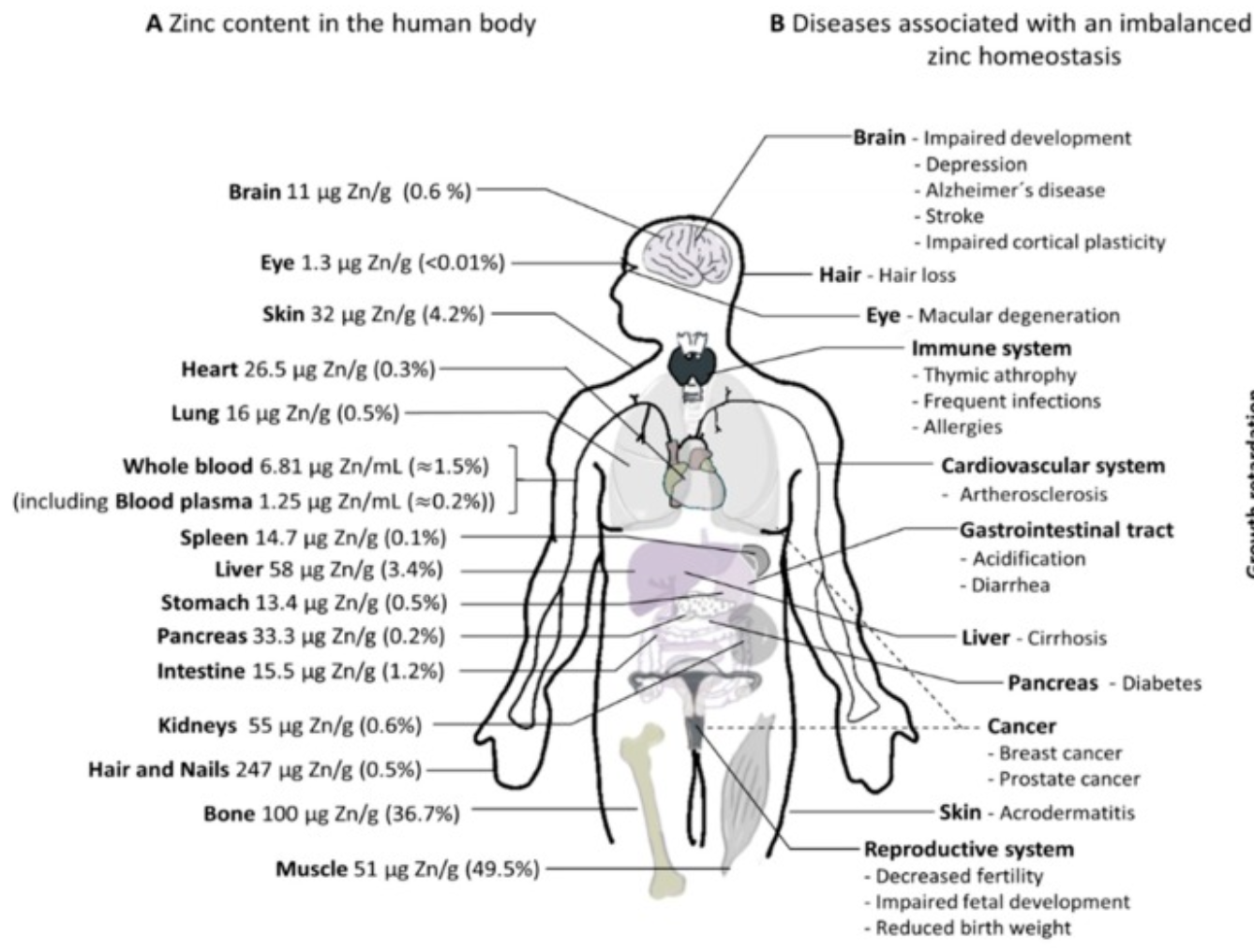

Zinc is an essential trace mineral that is integral to the way your cells function. Researchers estimate that over 3000 different cellular functions rely on zinc.[ref][ref]

This mineral is a component of many different types of biological molecules – impacting metabolism, immune function, skin barrier function, and more. Zinc is needed for the function of all cell types in all tissues and organs.

Let’s dig into the research on how and why zinc is important, the genes that encode the transporters, and how genetic variants can impact your need for zinc.

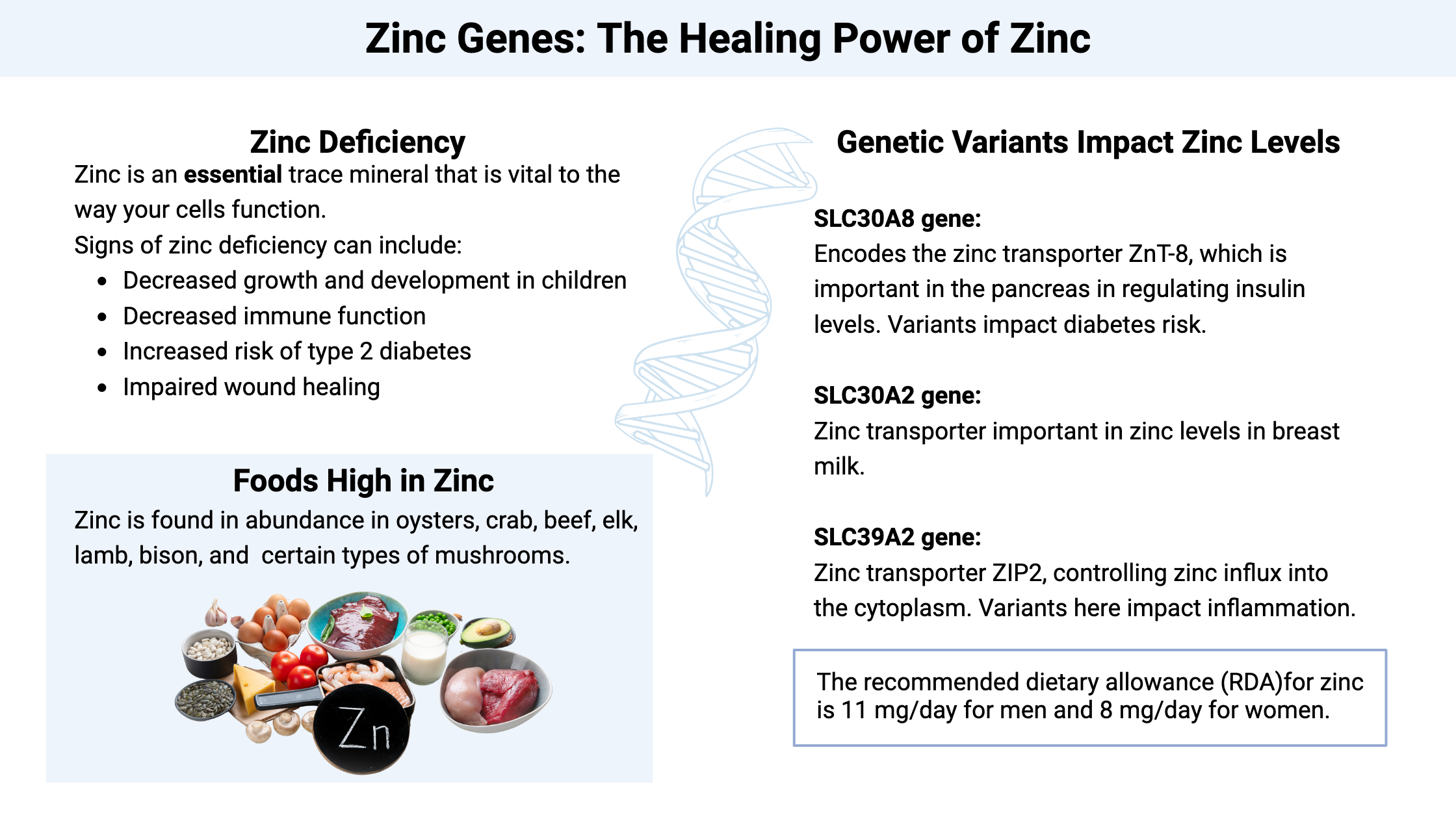

Dietary zinc insufficiency or deficiency:

We need to replenish our zinc stores daily (or nearly daily) from the foods that we eat. The body doesn’t have a long-term storage reservoir for zinc.[ref]

What happens when you don’t get enough zinc on a long-term basis? Signs of zinc deficiency can include:

- Decreased growth and development in children (a big problem in developing countries)

- Decreased immune function (getting more colds, respiratory or diarrheal illnesses than usual)

- Increased risk of type 2 diabetes (zinc is needed for beta-cell function in the pancreas)

- Impaired wound healing

Zinc supplementation has been shown to cut childhood mortality rates by 50% in developing countries. That is huge![ref]

What causes dietary zinc deficiency? The answer can be summed up as simply a diet that is high in phytates and low in animal foods.[ref][ref] Phytates bind to and reduce the intestinal absorption of zinc. Phytic acid, or phytate, is found in plant seeds, so a diet high in beans, grains, and nuts can be high in phytate, depending on how the food is cooked or processed. Animal protein contains both higher levels of zinc and increases the absorption of zinc.

It is estimated that over 1 billion people worldwide suffer from frank zinc deficiency, with some estimates as high as a third of the world’s population being zinc deficient.[ref][ref]

While most people in developed nations don’t have a frank zinc deficiency, a high percentage still have insufficient zinc intake. This can be especially true for older people with a poor diet and reduced intestinal absorption. People with celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, or alcohol addiction are more likely to have reduced intestinal absorption.

Dietary sources of zinc:

We need zinc regularly because the body doesn’t have a way to store it. Thus, regularly eating foods that contain zinc is important for optimal health.

Zinc is found in abundance in oysters, crab, beef, elk, lamb, bison, certain types of mushrooms, and fortified cereals.[ref]

Studies show that people on a vegetarian or vegan diet have a lower daily zinc intake and are at a greater risk for zinc deficiency.[ref] (See the Lifehacks section below for ways of tracking zinc intake and supplementing.)

Intestinal absorption and regulation:

First, you have to make sure the diet contains enough zinc, and then you also need to be able to absorb the zinc in the right amount. The body tightly regulates the amount of zinc absorbed — you don’t want too much or too little.

Zinc is absorbed in the intestines via zinc transport proteins. These zinc transporters are part of a feedback loop: when zinc levels are low in intestinal cells, this triggers the formation of more zinc transporters. When zinc levels increase to the right level, the expression of the zinc transport proteins decreases.[ref] The body is pretty awesome in the way that it can regulate micronutrient levels.

A dietary zinc deficiency, especially longer-term, can lead to a decrease in mucin production in the intestines. Zinc is one of the micronutrients needed for mucin production. Mucin lines the intestines and keeps bacteria and viruses away from the intestinal epithelial cells. When mucin is decreased, the risk of intestinal diseases and pathogenic infections rises.[ref]

Related article: Mucin and gut barrier function

Additionally, zinc is vital in cells that turn over rapidly – like intestinal cells and skin cells. Thus, a zinc deficiency can cause problems in intestinal barrier function relatively quickly.[ref]

Zinc transporters and regulation:

The cellular level of zinc needs to be tightly regulated since too much available zinc could cause oxidative stress. Metallothionein (MT) is a protein that can bind to zinc if levels are too high in a cell.[ref]

Two families of zinc-specific transporters help to control intracellular zinc levels. The SLC30 family of genes and the SLC39 family of genes encode these zinc transporters. Some of these genes are important during the development of the fetus, where zinc is an essential micronutrient, and others are specific to zinc regulation in different tissues.[ref]

SLC39A2 (ZIP2):

The SLC39A2 zinc transporter is also known as ZIP2 that moves zinc from outside of cells into the cytosol of cells. It is a pH-dependent and voltage-dependent, and can also transport cadmium and cobalt, but only when zinc levels are low.[ref] ZIP2 is important in skin health, heart health, and immune response. It is also important in the lungs and may play a role in the severity of cystic fibrosis.[ref][ref][ref]

SLC39A13 (ZIP13):

The ZIP13 zinc transporter is involved in moving zinc in the Golgi apparatus and cytoplasm. Rare mutations in this gene are linked to a form of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome.[ref]

SLC30A8:

The SLC30A8 gene codes for the zinc transporter ZnT-8. This zinc transporter is found in pancreatic beta-cells and transports the zinc from the cytoplasm into insulin secretory vesicles, where it stabilizes it and prevents degradation.[ref]

CA1 gene:

The CA1 gene codes for a carbonic anhydrase enzyme that binds to and uses zinc and catalyzes the reversible hydration of carbon dioxide, important in cellular respiration. Essentially, it is the enzyme needed for balancing out carbon dioxide, bicarbonate, and H+ ions, which then maintains a neutral pH in the body. Genetic variants in the CA1 gene are associated with higher or lower serum zinc levels.

Zinc deficiency and health outcomes

Zinc is vital to the immune system, and a lack of zinc can have detrimental effects, including increased susceptibility to infectious diseases, skin issues, impaired wound healing, and decreased antioxidant defense.

| Health Concern | How Zinc Deficiency Impacts It |

|---|---|

| Immune Function | Increased susceptibility to infections, NLRP3 activation |

| Skin & Hair | Dermatitis, alopecia, eczema |

| Wound Healing | Impaired recovery |

| Blood Sugar Regulation | Increased type 2 diabetes risk |

| Childhood Development | Stunted growth, higher mortality rates |

Zinc in the immune response

T-cells are an important part of our adaptive immune system’s defense against viruses and bacteria. T-cells are a type of white blood cell that is produced in the bone marrow and then travels to the thymus to mature into pathogen-fighting cells. The thymus is a small lymphatic system organ that is located in the upper chest, behind the breastbone. As we age, the thymus decreases in both size and function due to a process called thymus involution. The thymus is at its maximum size in adolescence.

Due to its significant role in the immune system, zinc deficiency is linked to decreased T-cell function, especially in aging. In animal studies, supplemental zinc increases the thickness of the thymic gland and increases T-cell function.[ref]

In addition, zinc helps to keep the NLRP3 inflammasome activation under control.[ref] Excess NLRP3 inflammasome activation can cause inflammatory damage and chronic inflammation.

Related article: NLRP3 inflammasome genes

Both primary and secondary antibody responses are decreased in zinc deficiency.[ref]

Which illnesses are worsened by zinc deficiency?

- For respiratory viruses, like the common cold, zinc can inhibit viral polymerase, reducing rhinovirus infections. It has also been shown to help with Covid.[ref]

- Zinc reduces the hepatitis C virus by inhibiting viral RNA polymerase and replication in

- For the flu, zinc helps to reduce influenza viral replication through a couple of zinc-dependent anti-viral proteins. [ref]

- Clinical trials show that zinc supplementation (in populations with dietary insufficiency) decreased diarrheal illnesses by 18% and pneumonia by 41%.[ref]

- Oral rehydration, along with zinc, helps to combat diarrheal illnesses in kids. This has significantly reduced the number of childhood deaths from diarrheal illness.[ref]

- Patients with more severe COVID-19 symptoms have lower zinc levels, on average, with more than half reaching the point of clinical zinc deficiency.[ref][ref]

Zinc for your skin and hair:

The epithelial cells that make up your skin require zinc, and since these cells turn over quickly, the skin is one of the first places where people notice zinc deficiency. Zinc deficiency can also cause hair loss.

Low zinc is linked to:[ref]

- dermatitis

- alopecia

- acne

- eczema

- dry, scaly skin

Zinc and mental health:

Studies show that low levels of zinc can increase the risk of mental health problems, such as depression. A meta-analysis showed that people with depression are more likely to have lower zinc levels, and intervention studies show that increasing zinc consumption alleviates depression in people.[ref]

Zinc and inflammation:

Zinc deficiency can play a role in chronic inflammation because zinc is a cofactor required in SOD1 (superoxide dismutase 1). SOD1 is a copper and zinc-dependent antioxidant that protects against lipid peroxidation and hydrogen peroxide. Essentially, zinc deficiency reduces antioxidant defence.[ref][ref]

Epigenetic role of zinc:

Recent research shows that zinc is an important cofactor in several genes that are involved in the epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Essentially, this means zinc is important in certain genes that turn on or off a bunch of other genes.

For example, a zinc transporter (ZIP10) is important in the epigenetic regulation of genes important in skin homeostasis. Other research shows zinc is required for several epigenetic enzymes, including DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs).[ref]

Zinc Genotype Report:

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks for low zinc:

How much zinc do you need?

At a glance:

- US RDA: Men: 11 mg/day | Women: 8 mg/day

- Upper Limit: 40 mg/day (adults)[ref]

Safety and toxicity:

The upper daily limit (UL) for zinc is set at 40mg/day. Longer-term supplementation at levels higher than this could result in adverse effects. The most common short-term effect is gastrointestinal discomfort. Intake of over 50 mg/day for 10 weeks can cause copper deficiency or low magnesium due to competition for the transporter. Symptoms include neurological problems such as loss of coordination, numbness, and weakness in the arms, legs, and feet.[ref][ref][ref]

Conditions that increase the need for zinc:

Illness, heavy physical activity, and pregnancy all increase the amount of zinc needed each day.[ref]

Different forms of zinc in supplements:

Zinc is available as supplements in various forms. Supplemental forms of zinc include:[ref][ref][ref][ref][ref]

- Zinc gluconate: A commonly available form used in many cold medications and nasal sprays. Easily absorbed.

- Zinc aspartate: Better absorbed than zinc gluconate, but not as commonly found in supplements.

- Zinc picolinate: It is more readily than the other forms, easily absorbed into the body to release zinc

- Zinc citrate: Only slightly soluble in water, this form tastes better and is used in syrups. It is well absorbed.

- Zinc acetate: This is also commonly used in cold and flu medications. Better absorption than zinc oxide.

- Zinc oxide: Little or no absorption from this source of zinc. It is used as a sunscreen alternative.

- Zinc sulfate: Poor absorption, similar to the zinc oxide form.

Side Effects from Zinc Supplements:

The most commonly reported side effect of supplemental zinc is stomach upset. If you find that a zinc supplement causes stomach pain, try decreasing the amount, taking it with food, or splitting it into very small doses at a couple of meals. Either look for a low-dose zinc or simply divide up the one that you already have.

Diet and Zinc:

If you don’t eat a lot of shellfish, beef, lamb, or fortified cereals, you may not get enough zinc in your diet. One way to know is to track what you eat for a week or so.

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

Molybdenum: Genetic Connections, Sulfur Metabolism, and Cofactor Deficiency

References: