Key takeaways:

~ The AMPD1 gene codes for an enzyme that converts AMP to IMP, which is particularly important for energy production in muscles during exercise.

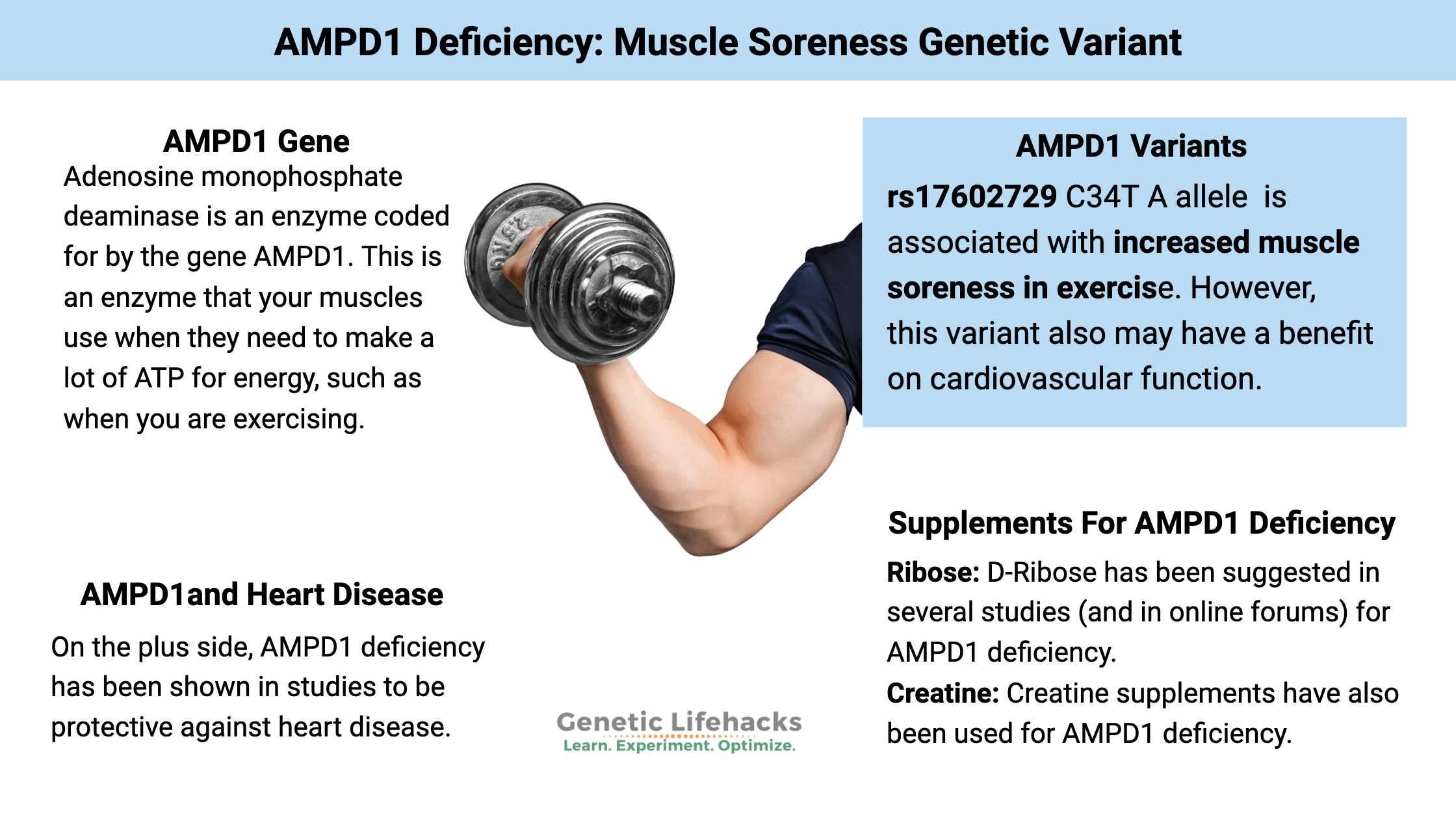

~ A common AMPD1 gene variant can decrease this conversion, leading to fatigue and muscle soreness after exercise.

~ Tradeoffs. People with AMPD1 deficiency may experience increased muscle soreness, but it also is protective against heart disease.

AMPD1 gene (Adenosine monophosphate deaminase):

Adenosine monophosphate deaminase is an enzyme coded for by the gene AMPD1, which acts in the skeletal muscles to convert AMP to IMP. In a nutshell, AMPD1 is an enzyme that your muscles use when they need to make a lot of ATP for energy, such as when you are exercising. A common variant of the AMPD1 gene decreases the conversion, leading to a build-up of AMP.

One study explains: “AMPD1 codes for the skeletal muscle isoform of myoadenylate deaminase (MAD). MAD promotes the deamination of adenosine monophosphate (AMP) to inosine monophosphate (IMP).”[ref]

This is all about energy production in the muscle, and AMPD1 is mainly expressed in fast-twitch muscle fibers. When it comes to exercise, people with decreased AMPD tend to get sore more easily after a hard workout. As one study puts it, people with the genetic variant that decreases AMPD get “muscle cramps, pain, and premature fatigue during exercise”.[ref]

Symptoms of AMPD1 deficiency:

AMPD1 deficiency, also known as myoadenylate deaminase deficiency, has varying effects on exercise performance, heart attack response, and methotrexate (cancer drug) response.

The main symptom of AMPD1 deficiency is that it causes sore muscles soon after a workout and sometimes muscle spasms when working out.[ref]

Prevalence of AMPD1 polymorphism:

A common AMPD1 genetic variant, known as C34T, causes a decrease in the function of this enzyme for people with one copy of the variant (heterozygous AMPD1 deficiency). This causes about a 60 – 84% decrease in enzyme activity.[ref]

People with two copies of this variant have a non-functioning enzyme. Caucasian and African populations carry one copy of the variant at a frequency of about 10%. It is much less frequent and rarely seen in other population groups, such as Asians.

Research studies on AMPD1 deficiency:

Exercise studies:

- People with one copy (heterozygous) of the AMPD1 allele “require longer rest periods between bouts of weight training, require longer between sessions and have increased perceived pain post-training”.[ref]

- In a study of elite triathlon athletes, AMPD1 was found to be the only significant genetic factor that negatively impacted performance time.[ref]

- A study of Lithuanian athletes found that none of the athletes carried the AA genotype. Additionally, one copy of the variant likely affected anaerobic performance more than aerobic performance.[ref]

- A study of elite rowers also found that the A allele was found much less often in the group.[ref]

Rheumatoid arthritis/methotrexate studies:

AMPD1 deficiency is associated with a good response to methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis.[ref][ref]

Long Covid and lactic acid levels:

A study involving long Covid patients found that lactic levels were higher after exercise. Those with the AMPD1 deficiency genotype had the highest lactic acid levels post-exercise (Nordic walking) compared to the typical AMPD1 genotype. Interestingly, the AMPD1 deficiency genotype had a greater improvement in lactic acid levels by the end of the 12-week study (however, they were still higher than the typical genotype). One takeaway from this is that continuing to exercise gave a greater improvement to the AMPD1 deficiency group, but they were still well above both the control group and the long covid with normal genotype groups.[ref]

Heart Disease:

On the plus side, AMPD1 deficiency may be protective against heart disease.[ref]

- A meta-study looked at the generally beneficial role of AMPD1 polymorphism in heart disease. The study showed that people with the A allele (see below) likely had better cardiac function.[ref]

- Another study found that being heterozygous for the AMPD1 variant led to a better prognosis in cardiovascular disease.[ref]

AMPD1 Genotype Report:

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Check out other Athletic Performance Genes and ACTN3

Lifehacks: Solutions for AMPD1 deficiency

Does AMPD1 deficiency mean that you can’t work out? Absolutely not!

Instead, it may mean that you want to modify the timing of your workout to decrease pain or muscle soreness. You may find that resting longer between weight-lifting sets in a workout helps, or that lower-intensity workouts may be better for you.

Supplements for AMPD1 deficiency:

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

References: