Key Takeaways:

~ Athleticism has a strong genetic component, which may make a difference at the level of elite or Olympic athletes.

~ Understanding your genetic variants can help you understand your muscle function and the pros and cons.

Do genes affect athletic performance?

After reading through a bunch of studies on the genetics of elite athletic performance, I’ve come away with an overall sense that for some people, athleticism will just come easier. For others, it will take a little more work.

To be honest, your genes are probably not the limiting factor for your athletic performance unless you are at the very top of your sport. Even at the top levels, there are always exceptions.

Moreover, reading through some of the research leaves me a bit disconcerted. Some of the research reads as almost a ‘how-to’ guide for selecting people for a sport based on their genetic profile.

First, a couple of terms to define:

Power sports are generally ones that require short bursts of power. Examples include sprinting, weight lifting, short-track biking, and gymnastics. Generally, these sports require more anaerobic muscle power.[ref]

Endurance sports include long-distance running, distance cycling, long-distance swimming, and cross-country skiing.

While the genetic variants listed below may make a difference between winning or not at the Olympic level, don’t let the lack of a ‘good’ genetic variant dissuade you from a sport you love.

Why do some people build muscle faster?

Muscle composition is partly genetic. We all know people who put on muscle easily and those who are long and lean, well suited for running. This doesn’t mean that people who are long and lean can’t put on some muscle mass with weight lifting, but it does mean that they may not put on as much muscle mass as quickly as others.

Does genetics play a role in muscle building?

The composition of muscle fiber (slow-twitch vs. fast-twitch) has been shown to be about 45% due to genetics and about 40% due to the environment (exercise, nutrition, etc.).[ref]

Studies show that the amount of slow-twitch (Type I) muscle ranges from 5 – 90% in thigh muscles. Slow-twitch muscle is best suited for long endurance and aerobic exercise – for example, long-distance runners. Type IIX muscle fibers (fast-twitch, glycolytic) are more suited to power sports and strength training.[ref]

Muscle Composition Genotype Report:

Lifehacks:

There are several specific ‘hacks’ that may benefit your athletic performance based on your genetic variants.

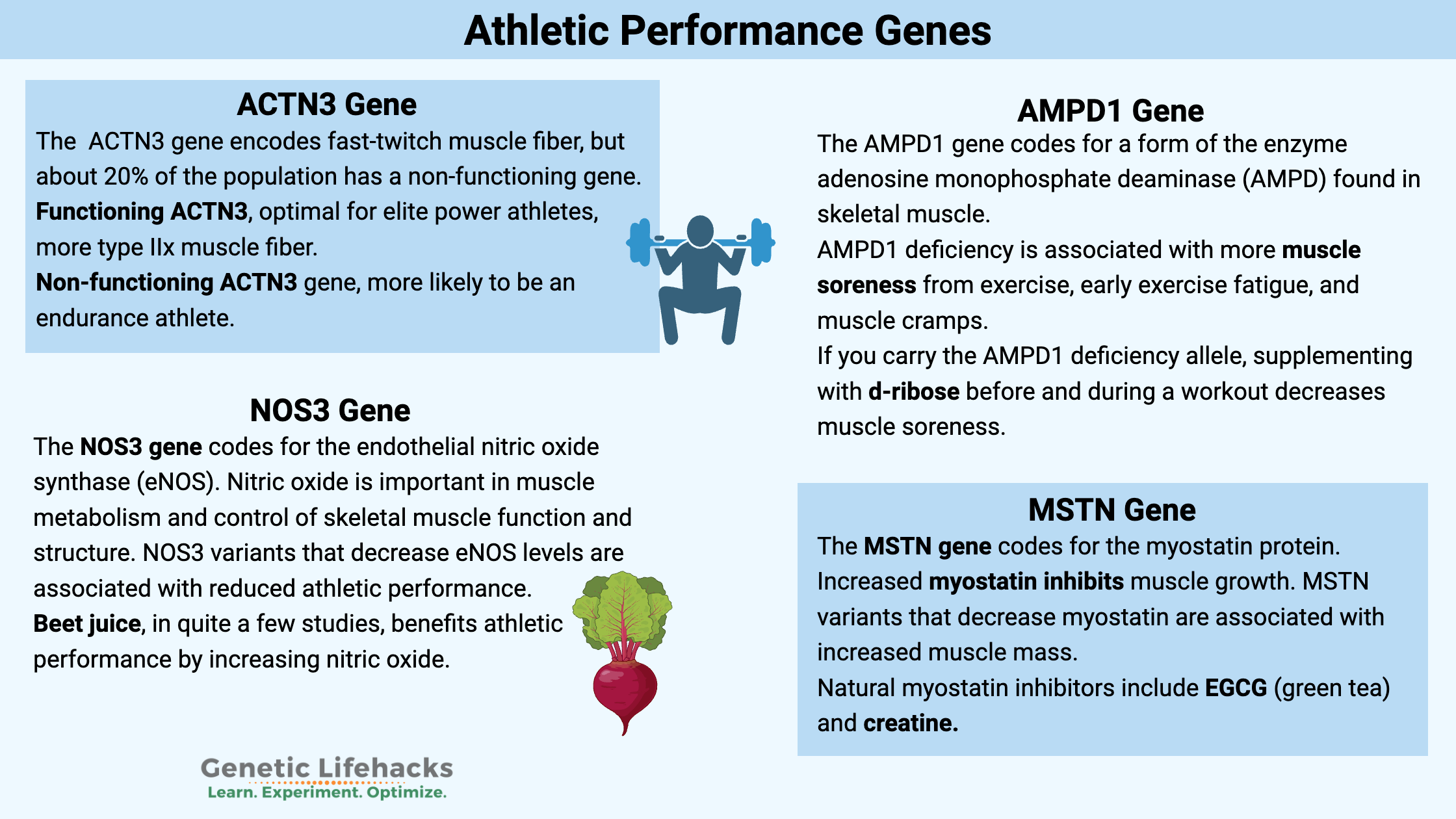

Beets for NOS3 variants:

Beet juice, in quite a few studies, benefits athletic performance by increasing nitric oxide. Not all studies agree, but a meta-analysis showed the majority of evidence points to an effect on NO from beets, which are high in inorganic nitrates.[ref] You can juice fresh beets for a pre-workout drink, or there are beet juice powdered supplements available as well. Look for an organic option if possible.

D-ribose for AMPD1 variant:

If you carry the AMPD1 deficiency allele, it may help to supplement with d-ribose before and during a workout. The d-ribose won’t necessarily decrease your exercise capacity, but it takes away the muscle soreness afterward.[ref][ref] D-ribose is a type of sugar and can be purchased in a powdered form. It has a mild, sweet taste and could be added to anything you drink during a workout.

Myostatin inhibitors:

If you don’t carry the myostatin variant that increases muscle mass, adding a natural myostatin inhibitor to your diet may give you a minor benefit.

Creatine

Related Articles and Topics:

Nitric Oxide Synthase: Heart health, blood pressure, and aging

Athletes are drinking beet juice to boost it, and people having chest pains pop nitroglycerine under their tongues with chest pain. What are we talking about here? Nitric oxide – a little molecule needed in just the right amount.

Quercetin: Scientific studies + genetic connections

Quercetin is a natural flavonoid acting as both an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory. This potent flavonoid is found in low levels in many fruits and vegetables, including elderberry, apples, and onions.

GLP-1 Receptor Agonists for Weight Loss: Genetic Interactions

GLP-1 receptor agonists, like semaglutide and liraglutide, are used for weight loss by increasing the body’s sensitivity to insulin and reducing hunger. However, genetic variants can alter the response in some people.

Creatine: Boosting Muscles and Increasing Brain Power

Creatine is an amino acid used in muscle tissue and the brain for energy in times of stress. Genes play a role in creatine synthesis. Find out what the research shows about creatine supplements for muscle mass and cognitive function.

References:

Aleksandra, Zarębska, et al. “The AGT Gene M235T Polymorphism and Response of Power-Related Variables to Aerobic Training.” Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, vol. 15, no. 4, Dec. 2016, pp. 616–24. PubMed Central, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5131215/.

Ben-Zaken, Sigal, et al. “Increased Prevalence of the IL-6-174C Genetic Polymorphism in Long Distance Swimmers.” Journal of Human Kinetics, vol. 58, Aug. 2017, pp. 121–30. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1515/hukin-2017-0070.

Chilibeck, Philip D., et al. “Effect of Creatine Supplementation during Resistance Training on Lean Tissue Mass and Muscular Strength in Older Adults: A Meta-Analysis.” Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 8, 2017, pp. 213–26. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.2147/OAJSM.S123529.

Chun, Jae Yeon, et al. “Andrographolide, an Herbal Medicine, Inhibits Interleukin-6 Expression and Suppresses Prostate Cancer Cell Growth.” Genes & Cancer, vol. 1, no. 8, Aug. 2010, pp. 868–76. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1177/1947601910383416.

Cieszczyk, Pawel, et al. “Distribution of the AMPD1 C34T Polymorphism in Polish Power-Oriented Athletes.” Journal of Sports Sciences, vol. 30, no. 1, 2012, pp. 31–35. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2011.623710.

Djarova, T., et al. “Performance Enhancing Genetic Variants, Oxygen Uptake, Heart Rate, Blood Pressure and Body Mass Index of Elite High Altitude Mountaineers.” Acta Physiologica Hungarica, vol. 100, no. 3, Sept. 2013, pp. 289–301. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1556/APhysiol.100.2013.3.5.

Domínguez, Raúl, et al. “Effects of Beetroot Juice Supplementation on Cardiorespiratory Endurance in Athletes. A Systematic Review.” Nutrients, vol. 9, no. 1, Jan. 2017, p. 43. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9010043.

Ginevičienė, Valentina, et al. “AMPD1 Rs17602729 Is Associated with Physical Performance of Sprint and Power in Elite Lithuanian Athletes.” BMC Genetics, vol. 15, May 2014, p. 58. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2156-15-58.

Grealy, Rebecca, et al. “Evaluation of a 7-Gene Genetic Profile for Athletic Endurance Phenotype in Ironman Championship Triathletes.” PLoS ONE, vol. 10, no. 12, Dec. 2015, p. e0145171. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145171.

Guilherme, João Paulo Limongi França, et al. “The AGTR2 Rs11091046 (A>C) Polymorphism and Power Athletic Status in Top-Level Brazilian Athletes.” Journal of Sports Sciences, vol. 36, no. 20, Oct. 2018, pp. 2327–32. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2018.1455260.

Gutierrez-Salmean, Gabriela, et al. “Effects of (−)-Epicatechin on Molecular Modulators of Skeletal Muscle Growth and Differentiation.” The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, vol. 25, no. 1, Jan. 2014, p. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.09.007. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.09.007.

Hennis, Philip J., et al. “Genetic Factors Associated with Exercise Performance in Atmospheric Hypoxia.” Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.z.), vol. 45, no. 5, 2015, pp. 745–61. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-015-0309-8.

Jones, N., et al. “A Genetic-Based Algorithm for Personalized Resistance Training.” Biology of Sport, vol. 33, no. 2, June 2016, pp. 117–26. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.5604/20831862.1198210.

KOSTEK, MATTHEW A., et al. “Myostatin and Follistatin Polymorphisms Interact with Muscle Phenotypes and Ethnicity.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, vol. 41, no. 5, May 2009, pp. 1063–71. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181930337.

Longhurst, J. C., and C. L. Stebbins. “The Power Athlete.” Cardiology Clinics, vol. 15, no. 3, Aug. 1997, pp. 413–29. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0733-8651(05)70349-0.

Mustafina, Leysan J., et al. “AGTR2 Gene Polymorphism Is Associated with Muscle Fibre Composition, Athletic Status and Aerobic Performance.” Experimental Physiology, vol. 99, no. 8, Aug. 2014, pp. 1042–52. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1113/expphysiol.2014.079335.

Nunes, Rafael Amorim Belo, et al. “Gender-Related Associations of Genetic Polymorphisms of α-Adrenergic Receptors, Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase and Bradykinin B2 Receptor with Treadmill Exercise Test Responses.” Open Heart, vol. 1, no. 1, Dec. 2014, p. e000132. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1136/openhrt-2014-000132.

Palizgir, Mohammad Taghi, et al. “Curcumin Reduces the Expression of Interleukin 1β and the Production of Interleukin 6 and Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha by M1 Macrophages from Patients with Behcet’s Disease.” Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology, vol. 40, no. 4, Aug. 2018, pp. 297–302. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1080/08923973.2018.1474921.

Ruiz, Jonatan R., et al. “The -174 G/C Polymorphism of the IL6 Gene Is Associated with Elite Power Performance.” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, vol. 13, no. 5, Sept. 2010, pp. 549–53. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2009.09.005.

Santiago, Catalina, et al. “The K153R Polymorphism in the Myostatin Gene and Muscle Power Phenotypes in Young, Non-Athletic Men.” PLoS ONE, vol. 6, no. 1, Jan. 2011, p. e16323. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0016323.

Saremi, A., et al. “Effects of Oral Creatine and Resistance Training on Serum Myostatin and GASP-1.” Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, vol. 317, no. 1–2, Apr. 2010, pp. 25–30. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2009.12.019.

Saunders, Colleen J., et al. “The Bradykinin Beta 2 Receptor (BDKRB2) and Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase 3 (NOS3) Genes and Endurance Performance during Ironman Triathlons.” Human Molecular Genetics, vol. 15, no. 6, Mar. 2006, pp. 979–87. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddl014.

Simoneau, J. A., and C. Bouchard. “Genetic Determinism of Fiber Type Proportion in Human Skeletal Muscle.” FASEB Journal: Official Publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, vol. 9, no. 11, Aug. 1995, pp. 1091–95. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1096/fasebj.9.11.7649409.

Wagner, D. R., et al. “Effects of Oral Ribose on Muscle Metabolism during Bicycle Ergometer in AMPD-Deficient Patients.” Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism, vol. 35, no. 5, 1991, pp. 297–302. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1159/000177660.

Yvert, Thomas P., et al. “AGTR2 and Sprint/Power Performance: A Case-Control Replication Study for Rs11091046 Polymorphism in Two Ethnicities.” Biology of Sport, vol. 35, no. 2, June 2018, pp. 105–09. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2018.71599.

Zarębska, Aleksandra, et al. “Association of Rs699 (M235T) Polymorphism in the AGT Gene with Power but Not Endurance Athlete Status.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 27, no. 10, Oct. 2013, pp. 2898–903. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e31828155b5.

Zmijewski, Piotr, et al. “The NOS3 G894T (Rs1799983) and -786T/C (Rs2070744) Polymorphisms Are Associated with Elite Swimmer Status.” Biology of Sport, vol. 35, no. 4, Dec. 2018, pp. 313–19. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2018.76528.

Zöllner, N., et al. “Myoadenylate Deaminase Deficiency: Successful Symptomatic Therapy by High Dose Oral Administration of Ribose.” Klinische Wochenschrift, vol. 64, no. 24, Dec. 1986, pp. 1281–90. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01785710.

Debbie Moon is the founder of Genetic Lifehacks. Fascinated by the connections between genes, diet, and health, her goal is to help you understand how to apply genetics to your diet and lifestyle decisions. Debbie has a BS in engineering from Colorado School of Mines and an MSc in biological sciences from Clemson University. Debbie combines an engineering mindset with a biological systems approach to help you understand how genetic differences impact your optimal health.