will see their genotype report below and the solutions in the Lifehacks section.

Your gut microbiome is unique to you. But why? Have you ever wondered why our gut microbes are different?

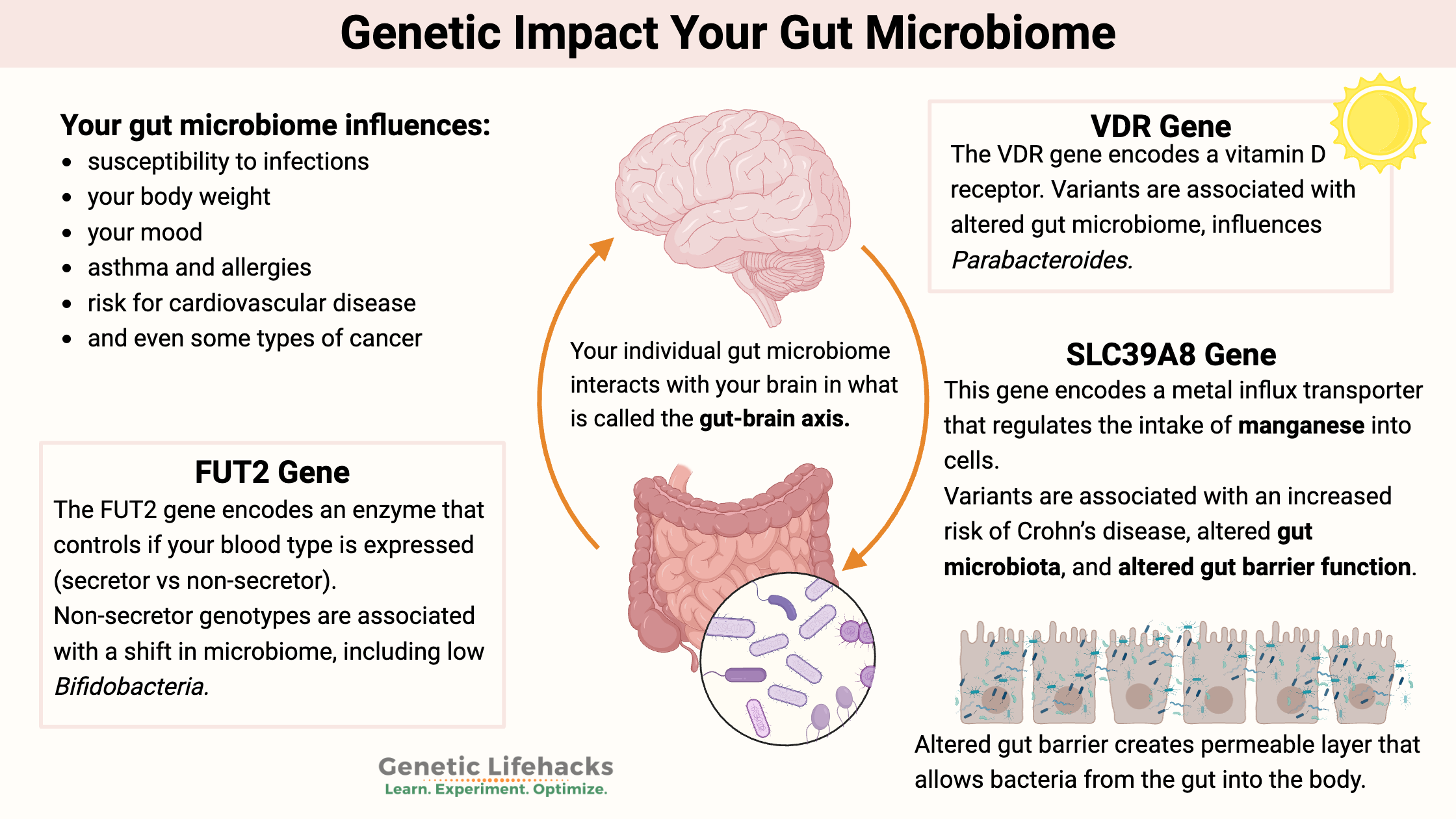

The human gut microbiome is made up of bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea, and obelisks that inhabit the ecosystem of our intestinal tract. It plays an integral role in our overall health.

Research increasingly shows that host genetics – your gene variants – play an important role in shaping which microbes thrive in our gut. Your genetic variants interact with environmental influences like diet, lifestyle, and medication to shape your gut microbiome.

Research shows that the influence of our gut microbes on our health is huge.

While it may seem odd to think of yourself as a host, as an environment… that is just what you are to the microbes living within or on you. And just like your genetic variants make you look and act differently than everyone else, your unique makeup also influences the types of microbes that can flourish within you.

Whether bloating, rumbling, or running to the bathroom, we have all experienced the misery at some point of not having happy intestinal function… But when it’s working just fine, most people tend to ignore the tiny microbes hard at work in their intestines.

In people who are overweight or obese, the gut microbiome increases how much energy is obtained from food.[ref] You are what you eat — and also what your microbes eat and produce fatty acids from.

Agnese, Doreen M., et al. “Human Toll-like Receptor 4 Mutations but Not CD14 Polymorphisms Are Associated with an Increased Risk of Gram-Negative Infections.” The Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 186, no. 10, Nov. 2002, pp. 1522–25. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1086/344893.

Beaumont, Michelle, et al. “Heritable Components of the Human Fecal Microbiome Are Associated with Visceral Fat.” Genome Biology, vol. 17, no. 1, Sept. 2016, p. 189. Springer Link, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-1052-7.

Castaño-Rodríguez, Natalia, et al. “Genetic Polymorphisms in the Toll-like Receptor Signalling Pathway in Helicobacter Pylori Infection and Related Gastric Cancer.” Human Immunology, vol. 75, no. 8, Aug. 2014, pp. 808–15. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humimm.2014.06.001.

Castellarin, Mauro, et al. “Fusobacterium Nucleatum Infection Is Prevalent in Human Colorectal Carcinoma.” Genome Research, vol. 22, no. 2, Feb. 2012, pp. 299–306. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.126516.111.

Chiu, Chih-Yung, et al. “Gut Microbial Dysbiosis Is Associated with Allergen-Specific IgE Responses in Young Children with Airway Allergies.” The World Allergy Organization Journal, vol. 12, no. 3, 2019, p. 100021. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.waojou.2019.100021.

Connelly, Tara M., et al. “An Interleukin-4 Polymorphism Is Associated with Susceptibility to Clostridium Difficile Infection in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Results of a Retrospective Cohort Study.” Surgery, vol. 156, no. 4, Oct. 2014, pp. 769–74. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2014.06.067.

Di Ciaula, Agostino, et al. “Gut Microbiota between Environment and Genetic Background in Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF).” Genes, vol. 11, no. 9, Sept. 2020, p. 1041. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11091041.

Erwin G. Zoetendal, Antoon D. L. Ak. “The Host Genotype Affects the Bacterial Community in the Human Gastronintestinal Tract.” Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease, vol. 13, no. 3, Jan. 2001, pp. 129–34. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1080/089106001750462669.

Goodrich, Julia K., et al. “Genetic Determinants of the Gut Microbiome in UK Twins.” Cell Host & Microbe, vol. 19, no. 5, May 2016, pp. 731–43. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2016.04.017.

Jie, Zhuye, et al. “The Gut Microbiome in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease.” Nature Communications, vol. 8, Oct. 2017, p. 845. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00900-1.

Kurilshikov, Alexander, et al. “Large-Scale Association Analyses Identify Host Factors Influencing Human Gut Microbiome Composition.” Nature Genetics, vol. 53, no. 2, Feb. 2021, pp. 156–65. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-020-00763-1.

Lach, Gilliard, et al. “Anxiety, Depression, and the Microbiome: A Role for Gut Peptides.” Neurotherapeutics, vol. 15, no. 1, Jan. 2018, pp. 36–59. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-017-0585-0.

Li, Dalin, et al. “A Pleiotropic Missense Variant in SLC39A8 Is Associated with Crohn’s Disease and Human Gut Microbiome Composition.” Gastroenterology, vol. 151, no. 4, Oct. 2016, pp. 724–32. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.06.051.

Lim, Mi Young, et al. “The Effect of Heritability and Host Genetics on the Gut Microbiota and Metabolic Syndrome.” Gut, vol. 66, no. 6, June 2017, pp. 1031–38. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311326.

Lorenz, Eva, et al. “Relevance of Mutations in the TLR4 Receptor in Patients with Gram-Negative Septic Shock.” Archives of Internal Medicine, vol. 162, no. 9, May 2002, pp. 1028–32. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.162.9.1028.

Nakata, Toru, et al. “A Missense Variant in SLC39A8 Confers Risk for Crohn’s Disease by Disrupting Manganese Homeostasis and Intestinal Barrier Integrity.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 117, no. 46, Nov. 2020, pp. 28930–38. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2014742117.

Steinhardt, Alberto Penas, et al. “A Functional Nonsynonymous Toll-like Receptor 4 Gene Polymorphism Is Associated with Metabolic Syndrome, Surrogates of Insulin Resistance, and Syndromes of Lipid Accumulation.” Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental, vol. 59, no. 5, May 2010, pp. 711–17. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2009.09.015.

Tilg, Herbert, and Arthur Kaser. “Gut Microbiome, Obesity, and Metabolic Dysfunction.” The Journal of Clinical Investigation, vol. 121, no. 6, June 2011, pp. 2126–32. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI58109.

Viala, Jérôme, et al. “Nod1 Responds to Peptidoglycan Delivered by the Helicobacter Pylori Cag Pathogenicity Island.” Nature Immunology, vol. 5, no. 11, Nov. 2004, pp. 1166–74. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/ni1131.

Wacklin, Pirjo, Jarno Tuimala, et al. “Faecal Microbiota Composition in Adults Is Associated with the FUT2 Gene Determining the Secretor Status.” PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 4, Apr. 2014, p. e94863. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094863.

Wacklin, Pirjo, Harri Mäkivuokko, et al. “Secretor Genotype (FUT2 Gene) Is Strongly Associated with the Composition of Bifidobacteria in the Human Intestine.” PLoS ONE, vol. 6, no. 5, May 2011, p. e20113. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020113.

Wang, Jun, et al. “Genome-Wide Association Analysis Identifies Variation in Vitamin D Receptor and Other Host Factors Influencing the Gut Microbiota.” Nature Genetics, vol. 48, no. 11, Nov. 2016, pp. 1396–406. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3695.