Key Takeaways:

~ Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD, fatty liver) is now the leading cause of liver problems worldwide, bypassing alcoholic liver disease.

~It is estimated that almost half of the population in the US has NAFLD

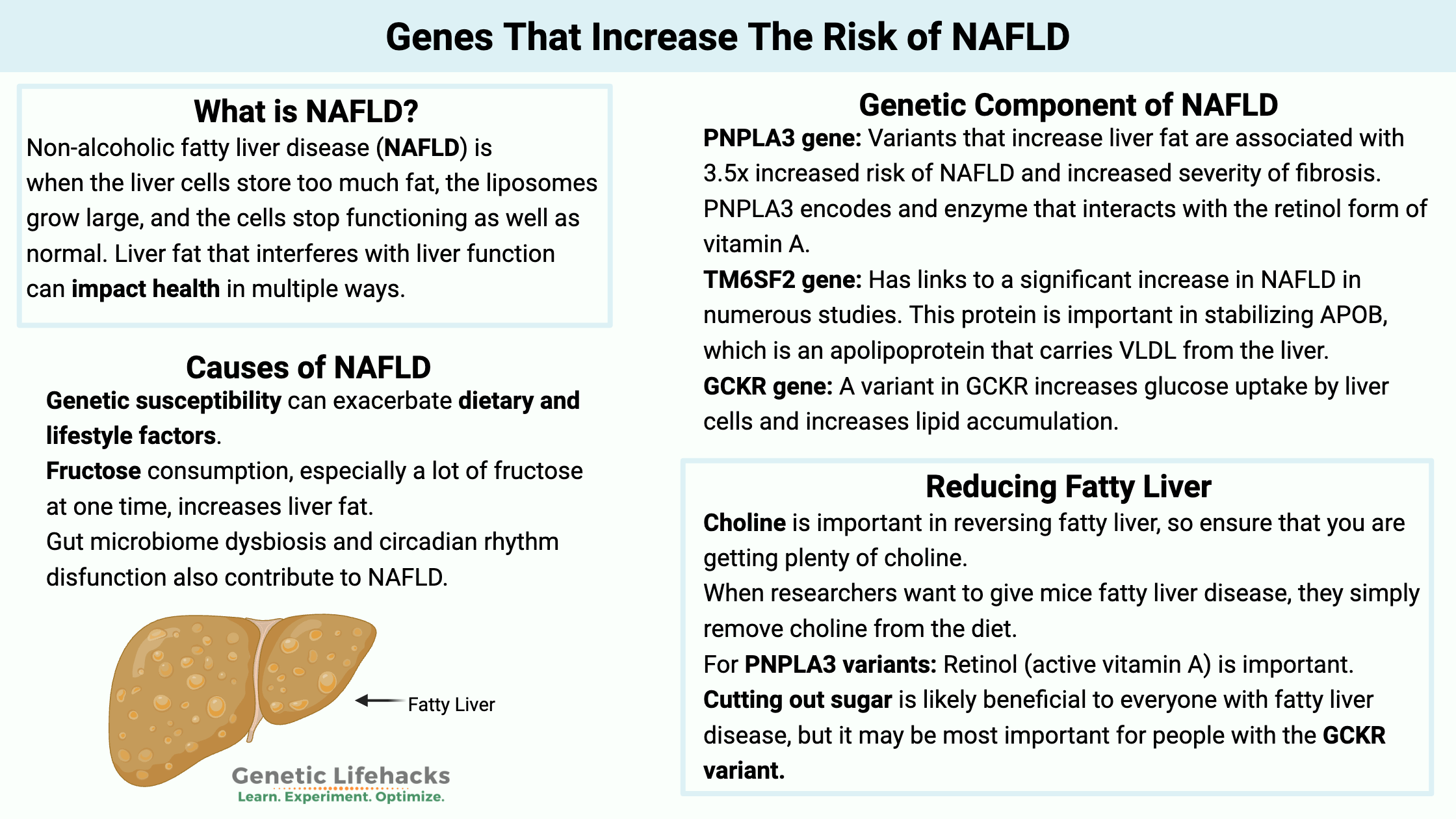

~ Fatty liver disease is caused by a combination of genetic susceptibility, diet, and lifestyle factors.[ref][ref]

~ Fatty liver is reversible, and understanding your genetic risk factors can help you prioritize the best path for you.

Members will see their genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

What is NAFLD (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease)?

Normal liver cells (hepatocytes) will store fat in small liposomes or fat-storage vesicles. When the liver cells store too much fat, the liposomes grow large, and the cells stop functioning as well as normal. NAFLD – non-alcoholic fatty liver disease – is caused by excess fat in the liver, and it is estimated to affect more than 25% of the population worldwide.[ref]

Symptoms of NAFLD:

Most people with NAFLD have no symptoms, but some will report fatigue and vague liver pain. NAFLD can cause elevated liver enzymes (AST and ALT), but not everyone with NAFLD has high liver numbers.

Why do we care about fatty liver if it causes few symptoms? Well, a percentage of people with fatty liver will progress to the point of inflammation and fibrosis (called NASH) and then liver failure.

While most people won’t end up needing a liver transplant, people with fatty livers may end up with metabolic dysfunction (insulin resistance, diabetes), increased inflammation, and liver mitochondrial dysfunction.[ref][ref]

The term NAFLD is now sometimes referred to as MAFLD, which stands for metabolic-dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease.[ref]

Liver fat that interferes with liver function can impact health in multiple ways. For example, the liver:

- stores glycogen, vitamins, minerals

- produces cholesterol and lipoproteins

- converts glucose into glycogen for stored energy

- creates the enzymes needed for metabolizing toxins and medications

- regulates a bunch of different amino acids

- makes some immune factors and clotting factors

- clears out bilirubin and ammonia

- makes bile for breaking down fats in foods

Everything you eat or drink that gets absorbed in the stomach or intestines first passes through the liver. It’s vital, and we all need it to function well for optimal health.

Why does the liver store fat?

Your liver cells always need a source of energy, and stored fat gives the cells continual access to an energy source.

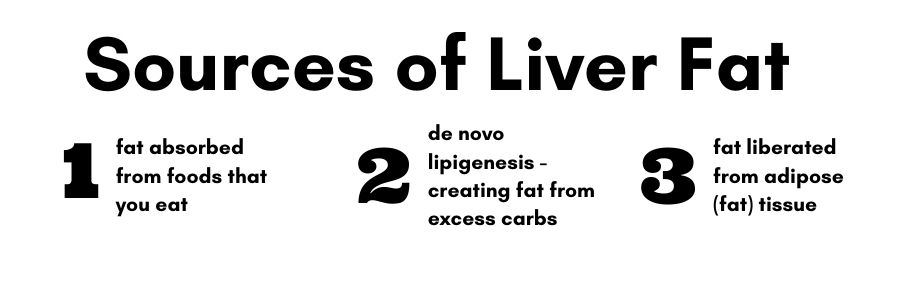

The liver can store fat from the foods you eat or create fatty acids through de novo lipogenesis, which converts excess carbs into fat. Additionally, the fat liberated from your adipose tissue can be stored in the liver. When the cells need energy, the liver can use up the stored fat via beta-oxidation. Furthermore, VLDL (very low-density lipoprotein) molecules secreted into the bloodstream can export fat from the liver.[ref]

Too much fat coming in (either from excess fatty foods or excess carbohydrates) and not enough fats being exported out (through burning it for energy or exporting as LDL) eventually results in fatty liver disease.

From fatty liver to NASH:

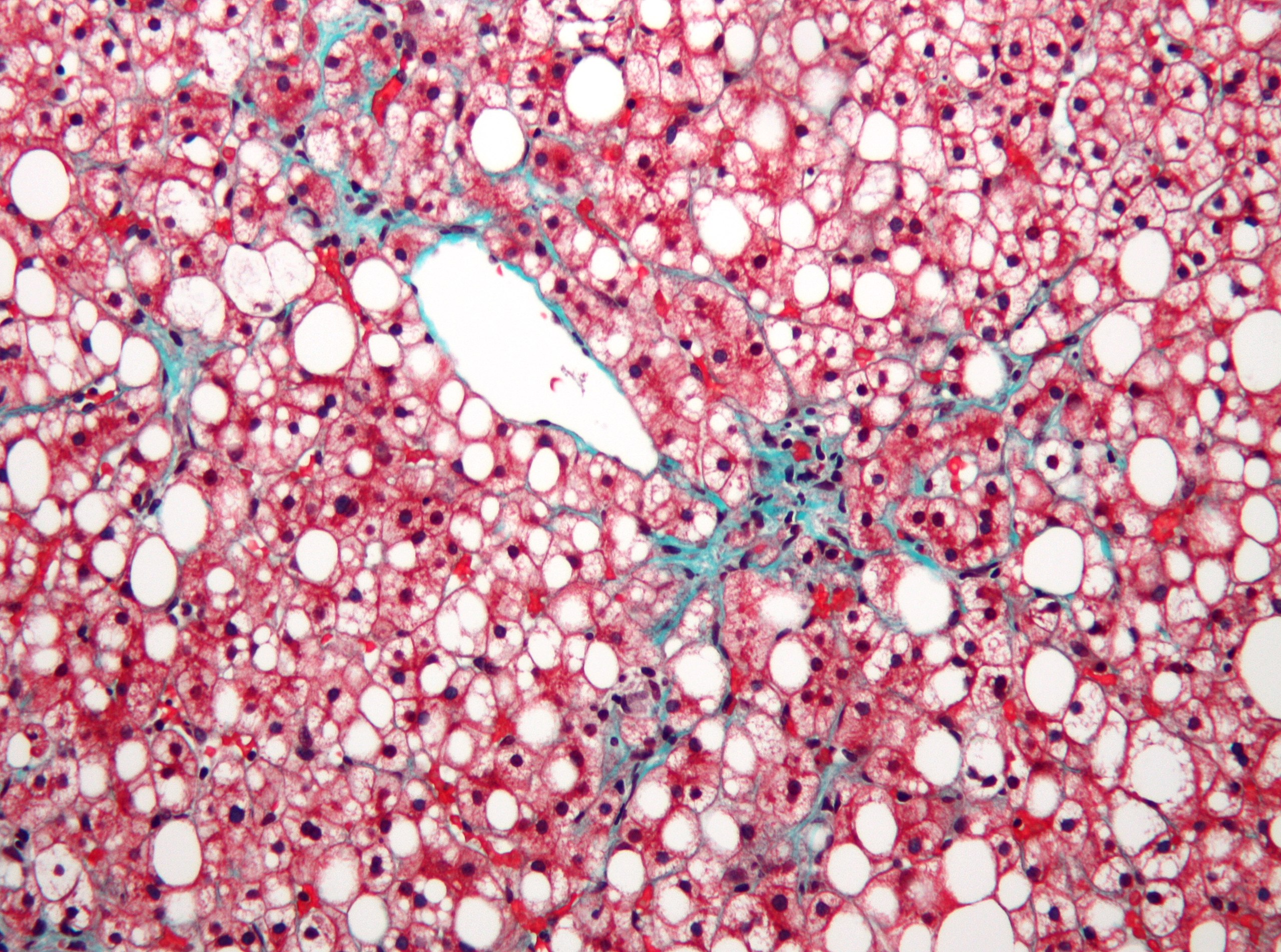

NASH (non-alcoholic steatohepatitis) is the stage of NAFLD when the liver cells are inflamed, and cell death occurs. At this point, fibrosis may occur in the liver to deal with the death of cells. Advanced fibrosis is known as cirrhosis.[ref]

About 20-30% of patients with NAFLD are likely to progress to NASH[ref]:

NAFLD –> NASH –> cirrhosis –>liver failure or liver cancer

Causes of fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

While fatty liver isn’t new, the number of people with fatty liver disease has skyrocketed in recent decades. Even kids are getting fatty liver now.[ref] So, what is causing all of this liver fat accumulation? It turns out that the answer may be more complex than doctors first thought.

The multiple-hit hypothesis theorizes that for NAFLD to occur, you need several insults acting together. It includes “insulin resistance, hormones secreted from the adipose tissue, nutritional factors, gut microbiota, and genetic and epigenetic factors.”[ref]

Is Fatty Liver Hereditary?

Genetic susceptibility can exacerbate dietary and lifestyle factors. NAFLD is considered ‘modestly heritable”, which means that genes play a role, but diet and lifestyle are really important.[ref]

Obesity and insulin resistance can also increase the risk. Genetics can play a role in obesity, but diet and lifestyle are also very important here.

Your gut bacteria (colon and small intestines) can increase the risk for NAFLD.

Excess iron is also linked to fatty liver due to oxidative stress (genetics comes into play here also).[ref]

Dietary causes of NAFLD:

In general, a ‘Western’ diet that includes more processed foods and fewer whole foods is implicated in NAFLD. Excess calories, whether from sugar or fat, are linked with an increased relative risk of fatty liver disease, and if you are overweight, losing some weight – no matter the diet you choose – will likely reduce liver issues. The studies on low carb, low fat, keto, DASH, and Mediterranean diets show similar benefits on fatty liver.[ref]

In most studies, soft drink consumption (containing liquid high fructose corn syrup) shows links to increasing the relative risk of NAFLD (OR=1.29). High red meat consumption also slightly increases the relative risk of NAFLD, while nut consumption shows a slightly decreased risk of fatty liver.[ref]

Fructose as a cause of fatty liver:

Fructose consumption, especially a lot of fructose at one time, increases liver fat. Even short-term high-fructose diets can increase liver fat. A study of healthy adults on a high fructose, iso-caloric diet showed increased liver fat (avg. of 137% increase) after nine days. The importance of this study is that the participants weren’t consuming more calories but rather just substituting fructose for other foods.[ref]

Why is fructose bad in comparison to glucose or other carbohydrates? Research shows that dietary fructose increases de novo lipogenesis (creation of fat) while depleting ATP and increasing mitochondrial ROS. Unlike glucose, fructose does not require insulin for its metabolism.[ref] Is eating an apple or a handful of berries going to cause fatty liver? Probably not, but dumping a bunch of fructose, such as drinking a cola sweetened with high fructose corn syrup, into the liver at one time will cause problems.

Choline is needed to prevent fatty liver:

One dietary component that stands out in NAFLD research is the need for choline.

When researchers want to give mice fatty liver disease, they simply remove choline from the diet. Researchers can also increase fatty liver by knocking out the PEMT (choline-related) gene in animals.[ref]

Human trials of choline supplementation (betaine) for NAFLD show mixed results.[ref][ref] On the other hand, increasing phosphatidylcholine may improve fatty liver. Liver biopsies of NAFLD and NASH patients show that their ratio of phosphatidylcholine to phosphatidylethanolamine is altered (low PC).[ref] A phase III clinical trial found a combination of phosphatidylcholine plus silybin to improve liver enzyme and liver histology.[ref]

Whatever diet you choose, from vegan to carnivore, the need for choline remains. Choline can be made by the body or obtained through diet. Genetics plays a role in how choline is synthesized in the body and metabolized in the liver. If you aren’t a champ at converting choline due to genetic variants, getting enough choline from your diet becomes more significant.

Related Article: Choline – an essential nutrient

Which foods are less likely to impact NAFLD?

It’s important to know also what is likely not to impact NAFLD risk significantly…Studies show that the dietary patterns that have no statistical impact on NAFLD include[ref]:

- whole-grain consumption

- refined grain consumption

- fish

- fruit intake

- vegetable intake

- dairy and eggs

- legumes

Beyond what you eat: additional NAFLD causes

It is easy to get a picture in your mind that fatty liver develops only in fat people who drink Big Gulps. Diet is important, of course, in fatty liver disease. But it isn’t all about what you eat. And while obesity is a risk factor for fatty liver, lean people can also develop the condition.[ref]

A recent study of NAFLD patients showed that 19% were lean, 52% were overweight, and 29% were obese.[ref] Considering that over 2/3 of adults in the US fall into the overweight or obese category, the percentages given aren’t that far off the normal distribution. So it is a mistake to think that being average weight prevents all cases of NAFLD.

In other words, the non-dietary factors in NAFLD are also important.

Circadian Misalignment and NAFLD:

A recent study shows that circadian misalignment, but not sleep duration, increases the relative risk of NAFLD due to metabolic dysfunction by more than 50% (OR=1.67). Circadian misalignment is defined in this study as falling asleep during the daytime, sleeping before 8 pm, or falling asleep after midnight.[ref]

Why would circadian misalignment increase NAFLD? The circadian clock, the body’s built-in 24-hour rhythms, controls how the liver functions at different times of the day. In addition to the body’s core circadian clock, organs such as the liver also have ‘peripheral clocks’ or rhythms based on the time of eating, sleep timing, and exposure to artificial light. For example, the liver creates enzymes needed to break down substances (food, drugs, toxins) at higher levels at times when the enzymes are likely to be required. Thus, the dysregulation or misalignment of the liver clock disrupts the way that the organ functions. It is linked to many health problems, including NAFLD.[ref]

Beyond circadian misalignment, another component of the circadian system, melatonin, may also be important in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. In addition to its role in circadian rhythm, melatonin acts as an antioxidant within cells and helps to maintain mitochondrial function. Animal research shows that supplemental melatonin attenuates NAFLD.[ref][ref] But what about in people?

A recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of 6mg of melatonin nightly 1 hr before bedtime showed that melatonin improves many NAFLD factors. The melatonin group showed statistical significance for decreased liver enzymes, decreased grade of fatty liver, and better metabolic measures.[ref]

SIBO, the gut microbiome, and fatty liver disease:

A number of interesting studies have been done on the link between the gut microbiome and NAFLD. In one study, the gut microbiome of people with genetic obesity was transplanted into germ-free mice. The mice then developed higher levels of liver fat.[ref]

Lipopolysaccharides (LPS), found on the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, increase intestinal permeability. The body recognizes LPS as being associated with pathogens and mounts an inflammatory response that increases intestinal permeability. Plus, increased intestinal permeability, which can be due to other reasons (e.g., diet), increases the ability of bacteria to translocate from the intestinal microbiome. Animal studies show that LPS directly increases fat in the liver.[ref]

SIBO is an overgrowth of bacteria in the small intestines. A higher prevalence of SIBO is found in people with NAFLD.[ref] Researchers think this could be due to several factors. The increased intestinal permeability (leaky gut) in SIBO patients seems linked with NAFLD, perhaps causing increased inflammation in the liver. Additionally, patients with NASH have altered gut microbiota.[ref]

Bile acids, the gallbladder, and NAFLD:

The liver synthesizes bile acids from cholesterol. After synthesis, the bile acids combine (conjugate) with glycine or taurine and head to the gallbladder for storage until needed. When you eat a meal containing fat, the gallbladder releases the conjugated bile acids to break down the fat for absorption in the intestines. Once in the intestines, these conjugated bile acids de-conjugate and are referred to as secondary bile acids.

People with fatty liver tend to have higher levels of bile acids and a higher ratio of secondary bile acids to conjugated bile acids. In addition to breaking down fats from your food, secondary bile acids also act as messengers that activate bile acid receptors such as TGR5. Additionally, excessive bile acids in the liver cause apoptosis (cell death) of liver cells. The Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) is also activated by bile acids, which regulate the creation of fat in the liver and gluconeogenesis.[ref]

Why all the information about bile acids? I’ll come back to all this in the lifehacks section with possible solutions based on bile acids.

Insulin resistance and fatty liver disease:

Fatty liver, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes often go together. The research on NAFLD points to a causal link to insulin resistance in the liver.[ref]

Moving from NAFLD to NASH to cirrhosis and/or cancer…

If half the US now has fatty liver, how many of us will end up with cirrhosis or cancer? It is an important question, and researchers strive to understand the differences in genetics and diet that can lead to NAFLD progression.

A recent metabolomics (small molecules or metabolites) study looked into the differences in fibrosis in people with NAFLD-HCC. The study showed that higher levels of choline derivatives and glutamine were present in people without liver fibrosis. In contrast, people with liver fibrosis had decreased monounsaturated fats, an increase in saturated fats, and an accumulation of branched amino acids.[ref]

Alcohol and fatty liver disease:

Since I’ve touched on various NAFLD causes, let’s talk about how alcohol also increases liver fat.

When you drink the occasional alcoholic drink or two, most of the alcohol breaks down (metabolized) via that alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme. But when you consume a lot of alcohol or chronically consume excess alcohol, more and more of the ethanol’s metabolism uses another enzyme called CYP2E1.

The CYP2E1 enzyme is elevated in people with either alcohol or non-alcohol-induced fatty liver. The elevated CYP2E1 enzyme also has links to insulin resistance and the progression of NAFLD to NASH.[ref]

When alcohol metabolism uses the CYP2E1 enzyme, a reduction occurs in NAD+ and the inhibition of beta-oxidation (using fat for fuel) in the liver cells. Additionally, the breakdown products of alcohol impair the secretion of fatty acids from the liver via VLDL. So you have the double-whammy of not secreting fat and also not burning fat, resulting in a buildup of fat in the liver. Circadian rhythm also comes into play here, with alcohol altering circadian clock genes. Finally, alcohol consumption alters the gut microbiome and intestinal permeability.[ref][ref]

Related Article: CYP2E1 Genetic Variants: Breaking down alcohol and more

NAFLD Genotype Report

Lifehacks: 8 Supplements and 9 diet and lifestyle changes for fatty liver

Figure out if you have fatty liver:

If you are obese and have diabetes, you likely have a fatty liver. Talk with your doctor to see if this holds true for you as an individual.

What if you are of average weight or if you are overweight but have no problem with insulin resistance? You would need to get an ultrasound from your doctor to know if you have fatty liver. Waiting for your liver enzymes to be elevated or for your liver to start hurting is not a good plan.

If you carry the genetic risk factors for NAFLD, it is a good idea to prioritize diet and liver health – whether to reverse your current fatty liver disease or to prevent it from happening.

Diet and lifestyle:

What you eat and how much you eat matters in NAFLD. Cut out junk food, avoid sodas, and eat a whole-food diet…the low-hanging fruit is the first place to start.

Weight Loss:

Losing weight, if you are overweight, should help to reduce fatty liver disease. The type of diet doesn’t seem to make much of a difference — so choose a diet that you can stick to long-term and that fits with your family and lifestyle.[ref][ref]

Choline:

Related Articles and Topics:

Problems with IBS? Personalized solutions based on your genes

There are multiple causes of IBS, and genetics can play a role in IBS symptoms. Pinpointing your cause can help you to figure out your solution.

Curcumin Supplements: Decreasing Inflammation

Have you heard that curcumin supplements offer a slew of health benefits? Discover the science behind how curcumin reduces inflammation for better outcomes in chronic diseases.

Circadian Rhythms: Genes at the Core of Our Internal Clocks

Circadian rhythms are the natural biological rhythms that shape our biology. Most people know about the master clock in our brain that keeps us on a wake-sleep cycle over 24 hours. This is driven by our master ‘clock’ genes.

Hypertension Risk Factor: CYP11B2 Variant

Hypertension risk can be modifiable in terms of diet and exercise however, genetics can play a part in risk. Learn more about how the CYP11B2 variant can increase the risk of hypertension.

References:

Abdelmalek, M. F., et al. “Betaine, a Promising New Agent for Patients with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: Results of a Pilot Study.” The American Journal of Gastroenterology, vol. 96, no. 9, Sept. 2001, pp. 2711–17. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04129.x.

Arendt, Bianca M., et al. “Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Is Associated with Lower Hepatic and Erythrocyte Ratios of Phosphatidylcholine to Phosphatidylethanolamine.” Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, vol. 38, no. 3, Mar. 2013, pp. 334–40. cdnsciencepub.com (Atypon), https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2012-0261.

Bahrami, Mina, et al. “The Effect of Melatonin on Treatment of Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Randomized Double Blind Clinical Trial.” Complementary Therapies in Medicine, vol. 52, Aug. 2020, p. 102452. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102452.

Bale, Govardhan, et al. “Whole-Exome Sequencing Identifies a Variant in Phosphatidylethanolamine N-Methyltransferase Gene to Be Associated With Lean-Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.” Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hepatology, vol. 9, no. 5, Oct. 2019, pp. 561–68. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jceh.2019.02.001.

Birkenfeld, Andreas L., and Gerald I. Shulman. “Non Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Hepatic Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes.” Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), vol. 59, no. 2, Feb. 2014, pp. 713–23. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26672.

Buchard, Benjamin, et al. “Two Metabolomics Phenotypes of Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease According to Fibrosis Severity.” Metabolites, vol. 11, no. 1, Jan. 2021, p. 54. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo11010054.

Buzzetti, Elena, et al. “The Multiple-Hit Pathogenesis of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD).” Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental, vol. 65, no. 8, Aug. 2016, pp. 1038–48. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2015.12.012.

Caligiuri, Alessandra, et al. “Molecular Pathogenesis of NASH.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 17, no. 9, Sept. 2016, p. 1575. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17091575.

Chen, Haizhen, et al. “Genetic Variant Rs72613567 of HSD17B13 Gene Reduces Alcohol‐related Liver Disease Risk in Chinese Han Population.” Liver International, vol. 40, no. 9, Sept. 2020, pp. 2194–202. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.14616.

Chen, Xinpei, et al. “The Roles of Transmembrane 6 Superfamily Member 2 Rs58542926 Polymorphism in Chronic Liver Disease: A Meta‐analysis of 24,147 Subjects.” Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine, vol. 7, no. 8, July 2019, p. e824. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.824.

Correia, Maria Almira, and Doyoung Kwon. “Why Hepatic CYP2E1-Elevation by Itself Is Insufficient for Inciting NAFLD/NASH: Inferences from Two Genetic Knockout Mouse Models.” Biology, vol. 9, no. 12, Dec. 2020, p. 419. www.mdpi.com, https://doi.org/10.3390/biology9120419.

Cunha, Guilherme Moura, et al. “Efficacy of a 2-Month Very Low-Calorie Ketogenic Diet (VLCKD) Compared to a Standard Low-Calorie Diet in Reducing Visceral and Liver Fat Accumulation in Patients With Obesity.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 11, 2020, p. 607. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.00607.

Ding, Ren-Bo, et al. “Emerging Roles of SIRT1 in Fatty Liver Diseases.” International Journal of Biological Sciences, vol. 13, no. 7, July 2017, pp. 852–67. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.19370.

Forsyth, Christopher B., et al. “Circadian Rhythms, Alcohol and Gut Interactions.” Alcohol (Fayetteville, N.Y.), vol. 49, no. 4, June 2015, pp. 389–98. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcohol.2014.07.021.

Grizales, Ana Maria, et al. “Metabolic Effects of Betaine: A Randomized Clinical Trial of Betaine Supplementation in Prediabetes.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 103, no. 8, Aug. 2018, pp. 3038–49. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2018-00507.

Hagström, Hannes, et al. “Risk for Development of Severe Liver Disease in Lean Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Long-Term Follow-up Study.” Hepatology Communications, vol. 2, no. 1, Jan. 2018, pp. 48–57. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep4.1124.

He, Kaiyin, et al. “Food Groups and the Likelihood of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The British Journal of Nutrition, vol. 124, no. 1, pp. 1–13. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114520000914.

—. “Food Groups and the Likelihood of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The British Journal of Nutrition, vol. 124, no. 1, pp. 1–13. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114520000914.

Kanda, Tatsuo, et al. “Molecular Mechanisms: Connections between Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Steatohepatitis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 21, no. 4, Feb. 2020, p. 1525. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21041525.

—. “Molecular Mechanisms: Connections between Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Steatohepatitis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 21, no. 4, Feb. 2020, p. 1525. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21041525.

Kars, Marleen, et al. “Tauroursodeoxycholic Acid May Improve Liver and Muscle but Not Adipose Tissue Insulin Sensitivity in Obese Men and Women.” Diabetes, vol. 59, no. 8, Aug. 2010, pp. 1899–905. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.2337/db10-0308.

Kitamoto, Takuya, et al. “Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing and Fine Linkage Disequilibrium Mapping Reveals Association of PNPLA3 and PARVB with the Severity of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.” Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 59, no. 5, May 2014, pp. 241–46. www.nature.com, https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2014.17.

Kotronen, A., et al. “A Common Variant in PNPLA3, Which Encodes Adiponutrin, Is Associated with Liver Fat Content in Humans.” Diabetologia, vol. 52, no. 6, June 2009, pp. 1056–60. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-009-1285-z.

Li, Yuan, et al. “Association of TM6SF2 Rs58542926 Gene Polymorphism with the Risk of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Colorectal Adenoma in Chinese Han Population.” BMC Biochemistry, vol. 20, no. 1, Feb. 2019, p. 3. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12858-019-0106-3.

Loguercio, Carmela, et al. “Silybin Combined with Phosphatidylcholine and Vitamin E in Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Free Radical Biology & Medicine, vol. 52, no. 9, May 2012, pp. 1658–65. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.02.008.

Luukkonen, Panu K., et al. “Human PNPLA3-I148M Variant Increases Hepatic Retention of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids.” JCI Insight, vol. 4, no. 16, Aug. 2019. insight.jci.org, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.127902.

Ma, Yanling, et al. “HSD17B13 Is a Hepatic Retinol Dehydrogenase Associated with Histological Features of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.” Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), vol. 69, no. 4, Apr. 2019, pp. 1504–19. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.30350.

Macaluso, Fabio Salvatore, et al. “Genetic Background in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Comprehensive Review.” World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG, vol. 21, no. 39, Oct. 2015, pp. 11088–111. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i39.11088.

—. “Genetic Background in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Comprehensive Review.” World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG, vol. 21, no. 39, Oct. 2015, pp. 11088–111. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i39.11088.

Marzuillo, Pierluigi, et al. “Pediatric Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: New Insights and Future Directions.” World Journal of Hepatology, vol. 6, no. 4, Apr. 2014, pp. 217–25. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v6.i4.217.

Meroni, Marica, et al. “Mboat7 Down-Regulation by Hyper-Insulinemia Induces Fat Accumulation in Hepatocytes.” EBioMedicine, vol. 52, Feb. 2020, p. 102658. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102658.

Miele, Luca, et al. “Increased Intestinal Permeability and Tight Junction Alterations in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.” Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), vol. 49, no. 6, June 2009, pp. 1877–87. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22848.

Mukherji, Atish, et al. “The Circadian Clock and Liver Function in Health and Disease.” Journal of Hepatology, vol. 71, no. 1, July 2019, pp. 200–11. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2019.03.020.

Muzica, Cristina M., et al. “Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Bidirectional Relationship.” Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, vol. 2020, Dec. 2020, p. 6638306. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6638306.

Nobili, V., et al. “Comparison of the Phenotype and Approach to Pediatric Versus Adult Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.” Gastroenterology, vol. 150, no. 8, June 2016, pp. 1798–810. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.03.009.

—. “Comparison of the Phenotype and Approach to Pediatric Versus Adult Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.” Gastroenterology, vol. 150, no. 8, June 2016, pp. 1798–810. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.03.009.

Ou, Tzu-Hsuan, et al. “Melatonin Improves Fatty Liver Syndrome by Inhibiting the Lipogenesis Pathway in Hamsters with High-Fat Diet-Induced Hyperlipidemia.” Nutrients, vol. 11, no. 4, Mar. 2019, p. E748. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11040748.

Pani, Arianna, et al. “Inositol and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review on Deficiencies and Supplementation.” Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 11, Nov. 2020, p. 3379. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113379.

Parra-Vargas, Marcela, et al. “Nutritional Approaches for the Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: An Evidence-Based Review.” Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 12, Dec. 2020, p. 3860. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123860.

Phipps, Meaghan, and Julia Wattacheril. “Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) in Non-Obese Individuals.” Frontline Gastroenterology, vol. 11, no. 6, Dec. 2019, pp. 478–83. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1136/flgastro-2018-101119.

Piao, Yun-Feng, et al. “Relationship between Genetic Polymorphism of Cytochrome P450IIE1 and Fatty Liver.” World Journal of Gastroenterology, vol. 9, no. 11, Nov. 2003, pp. 2612–15. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v9.i11.2612.

Santoro, Nicola, et al. “Variant in the Glucokinase Regulatory Protein (GCKR) Gene Is Associated with Fatty Liver in Obese Children and Adolescents.” Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), vol. 55, no. 3, Mar. 2012, pp. 781–89. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.24806.

Schwarz, Jean-Marc, et al. “Effect of a High-Fructose Weight-Maintaining Diet on Lipogenesis and Liver Fat.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 100, no. 6, June 2015, pp. 2434–42. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2014-3678.

Seitz, Helmut K., et al. “Alcoholic Liver Disease.” Nature Reviews. Disease Primers, vol. 4, no. 1, Aug. 2018, p. 16. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-018-0014-7.

Sherriff, Jill L., et al. “Choline, Its Potential Role in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, and the Case for Human and Bacterial Genes12.” Advances in Nutrition, vol. 7, no. 1, Jan. 2016, pp. 5–13. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3945/an.114.007955.

Softic, Samir, et al. “Role of Dietary Fructose and Hepatic de Novo Lipogenesis in Fatty Liver Disease.” Digestive Diseases and Sciences, vol. 61, no. 5, May 2016, pp. 1282–93. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-016-4054-0.

Sookoian, Silvia, and Carlos J. Pirola. “Meta-Analysis of the Influence of I148M Variant of Patatin-like Phospholipase Domain Containing 3 Gene (PNPLA3) on the Susceptibility and Histological Severity of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.” Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.), vol. 53, no. 6, June 2011, pp. 1883–94. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.24283.

Stacchiotti, Alessandra, et al. “Melatonin Effects on Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Are Related to MicroRNA-34a-5p/Sirt1 Axis and Autophagy.” Cells, vol. 8, no. 9, Sept. 2019, p. 1053. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8091053.

Strnad, Pavel, et al. “Heterozygous Carriage of the Alpha1-Antitrypsin Pi*Z Variant Increases the Risk to Develop Liver Cirrhosis.” Gut, vol. 68, no. 6, June 2019, pp. 1099–107. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316228.

Su, Wen, et al. “Role of HSD17B13 in the Liver Physiology and Pathophysiology.” Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, vol. 489, June 2019, pp. 119–25. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2018.10.014.

Teschke, Rolf. “Alcoholic Liver Disease: Alcohol Metabolism, Cascade of Molecular Mechanisms, Cellular Targets, and Clinical Aspects.” Biomedicines, vol. 6, no. 4, Nov. 2018, p. E106. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines6040106.

Wagenknecht, Lynne E., et al. “Correlates and Heritability of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in a Minority Cohort.” Obesity, vol. 17, no. 6, 2009, pp. 1240–46. Wiley Online Library, https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2009.4.

Wang, Ruirui, et al. “Genetically Obese Human Gut Microbiota Induces Liver Steatosis in Germ-Free Mice Fed on Normal Diet.” Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 9, 2018, p. 1602. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01602.

Williams, Christopher D., et al. “Prevalence of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis among a Largely Middle-Aged Population Utilizing Ultrasound and Liver Biopsy: A Prospective Study.” Gastroenterology, vol. 140, no. 1, Jan. 2011, pp. 124–31. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.038.

Xia, Yan, et al. “Meta-Analysis of the Association between MBOAT7 Rs641738, TM6SF2 Rs58542926 and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Susceptibility.” Clinics and Research in Hepatology and Gastroenterology, vol. 43, no. 5, Oct. 2019, pp. 533–41. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinre.2019.01.008.

Yan, Hong-Mei, et al. “Efficacy of Berberine in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.” PloS One, vol. 10, no. 8, 2015, p. e0134172. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0134172.

Ye, Qing, et al. “Association between the HFE C282Y, H63D Polymorphisms and the Risks of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Liver Cirrhosis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 5,758 Cases and 14,741 Controls.” PLOS ONE, vol. 11, no. 9, Sept. 2016, p. e0163423. PLoS Journals, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163423.

Zhou, Jin, et al. “Gut Microbiota and Their Metabolites in the Progression of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.” Hepatoma Research, vol. 7, Jan. 2021, p. 11. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.20517/2394-5079.2020.134.