Key takeaways:

- Pantothenic acid (vitamin B5) is the precursor for coenzyme A, which is fundamental for mitochondrial energy production.

- Vitamin B5 is especially important in the brain. Post-mortem brain studies show significantly lower vitamin B5 levels in Lewy body dementia, Alzheimer’s, and Huntington’s disease.

- Rare PANK2 mutations cause pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN).

- Pantothenate produced by gut bacteria increases GLP-1 secretion, and supplementing with pantothenate reduced sugar cravings in diabetics with low levels of this microbe.

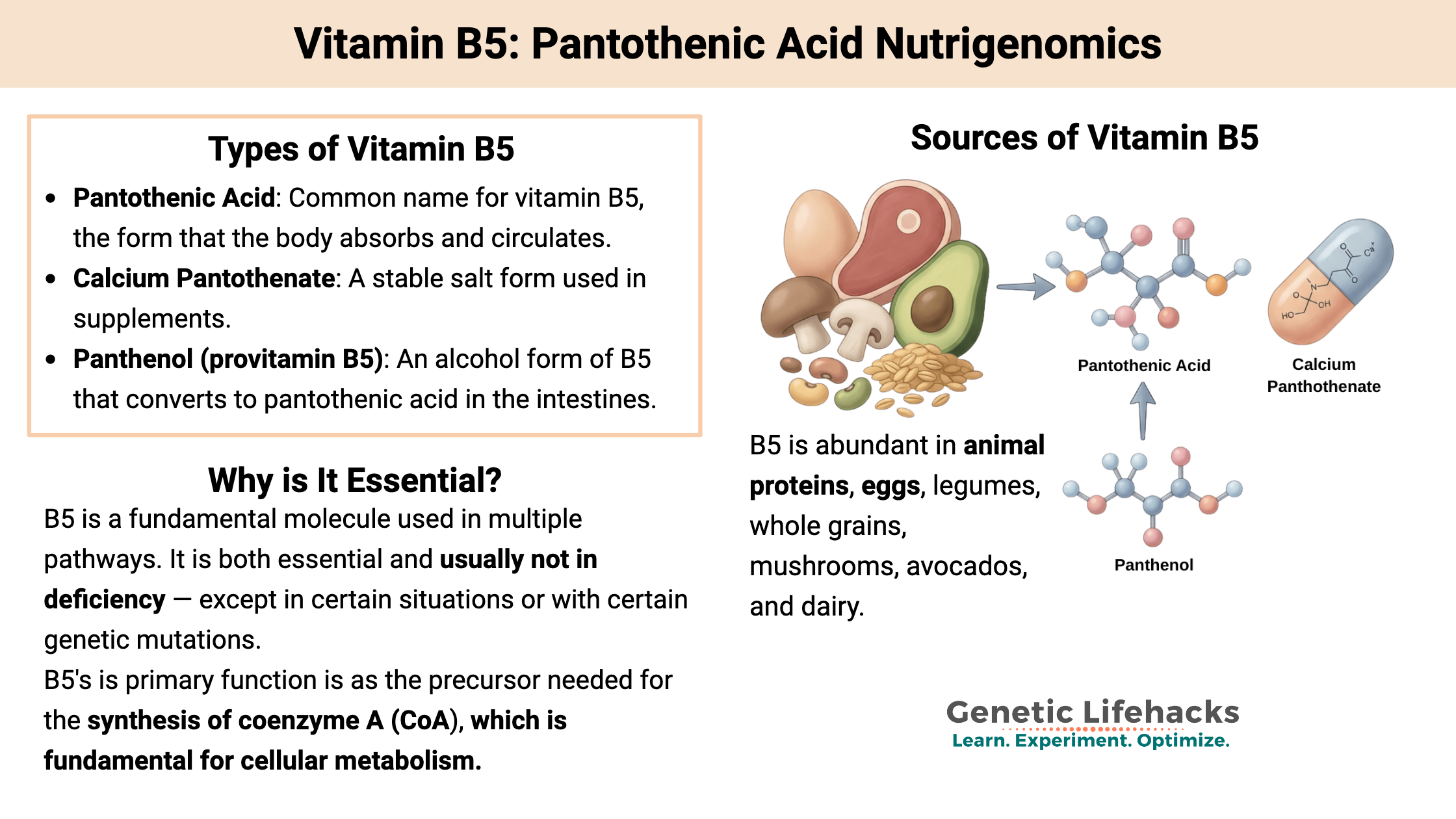

What is Pantothenic Acid, and Why is It Essential?

Pantothenic acid, also known as vitamin B5, is an essential water-soluble B vitamin that is found in many foods and is necessary for life in all animals. The name comes from the Greek word pantothen, meaning from everywhere. It serves as the precursor used to synthesize coenzyme A, which plays an integral role in energy production in the mitochondria. It is also used in iron regulation, peptide hormone production, and myelin production.

Sources of vitamin B5:

Pantothenic acid is found in a wide variety of foods, including vegetables and meats. Dietary deficiency is rare. It is absorbed in the intestines and can also be produced by intestinal bacteria.

Forms and sources:

- Pantothenic Acid: The common name for vitamin B5, the form that the body absorbs and circulates.

- Calcium Pantothenate: A stable salt form used in supplements.

- Food Sources: Abundant in animal proteins, eggs, legumes, whole grains, mushrooms, avocados, and dairy.

- Panthenol (provitamin B5): An alcohol form of B5 that converts to pantothenic acid in the intestines.

Note: Pantene Pro-V hair care products are named for containing the panthenol form of provitamin B5.

Before exploring deficiency symptoms and genetic factors, let’s look at how the body uses this essential vitamin.

What is pantothenic acid used for?

| Function | Importance |

|---|---|

| Energy Production | Building block for Coenzyme A (CoA), which helps convert food into energy. |

| Hormone Synthesis | Important for making peptide hormones (POMC and α-MSH) |

| Metabolism | Synthesis and metabolism of proteins, fats, and carbohydrates. |

| Cellular Health | Involved in the Krebs cycle (energy generation) and fatty acid synthesis. |

As a fundamental molecule used in multiple ways, pantothenic acid is both essential and usually not in deficiency — except in certain situations or with certain genetic mutations.

Let’s take a look at how the body uses vitamin B5, and then go into the symptoms and causes of deficiency.

Coenzyme A synthesis:

The primary function of pantothenic acid is as the precursor needed for the synthesis of coenzyme A (CoA), which is fundamental for cellular metabolism.

CoA is synthesized from pantothenate, and the initial rate-limiting step in CoA biosynthesis is governed by the pantothenate kinase enzymes (PANK1-PANK4 genes). Dysregulation of the pantothenate kinases causes significant disruption to cellular metabolism.[ref]

The CoA Biosynthesis Pathway:

Pantothenic acid undergoes five enzymatic steps to become CoA:

- Pantothenic acid + ATP → 4′-phosphopantothenate (via pantothenate kinases, PANK2, the rate-limiting step)

- Addition of cysteine

- Decarboxylation to form pantetheine

- Phosphorylation to 4′-phosphopantetheine

- Addition of ATP/adenosine to form CoA

The addition of an acetyl moiety to coenzyme A forms acetyl-CoA, which is then used in mitochondrial energy production as well as for lipid synthesis and acetylation reactions. The acetyl group is added through glycolysis (breakdown of sugar) or through the breakdown of fatty acids in beta-oxidation.[ref]

There’s a feedback mechanism in the cells that balances out the formation of acetyl-CoA, and when acetyl-CoA levels are high, pantothenate kinase (the first step enzyme) is inhibited.

Side note: Acetyl-CoA is a fundamental molecule used by all life forms, from bacteria to fungi to plants to humans.[ref]

Additional ways vitamin B5 is used:

While the function of coenzyme A is essential in mitochondrial energy (ATP) production, coenzyme A (derived from B5) is used in about 4% of cellular enzyme reactions.

Fatty acid synthesis: When there is excess glucose available, coenzyme A helps to balance metabolism by converting glucose to fatty acids.[ref]

Appetite and sugar cravings: A 2025 study showed that the pantothenate released by specific microbes interacts with GLP-1 in sugar cravings. Higher pantothenate production by Bacteroides vulgatus in the gut increased GLP-1 secretion. The study also showed that adding pantothenate reduced sugar cravings in diabetics with low B. vulgatus in the gut.[ref]

Myelin synthesis: Vitamin B5 localizes to myelin-containing nerves, and acetyl-CoA is essential for the synthesis of fatty-acyl chains of myelin in the brain and peripheral nervous system.[ref]

Peptide hormone synthesis: Coenzyme A is also involved in regulating the activity of peptide hormones, including POMC and α-MSH.[ref]

Folate cycle: The enzyme 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase (ALDH1L1, ALDH1L2 genes) catalyzes the conversion of 10-formyltetrahydrofolate to tetrahydrofolate using the vitamin B5 derivative 4’-phosphopantetheine. [ref][ref]

Iron regulation: While the full details aren’t yet known, pantothenic acid and the PANK2 enzyme interact with iron regulation, with low B5 increasing iron accumulation.[ref]

Symptoms of Pantothenic Acid Deficiency:

While uncommon, a deficiency of vitamin B5 due to genetic mutations or malnutrition can cause:[ref][ref]

- fatigue, irritability, listlessness

- burning feet

- numbness in the hands and feet

- paresthesia and muscle cramps

- restlessness, sleep disturbances

- nausea, vomiting, and abdominal cramps

Mice that are deficient in pantothenic acid develop graying of the fur, movement disorder, and skin irritation.[ref]

Absorption and transport:

Vitamin B5 is readily absorbed from foods as they are broken down in the intestines. It is then transported in the free form in the blood. It is rapidly taken up in red blood cells and tissues.[ref]

Blood-brain barrier:

Pantothenic acid crosses the blood-brain barrier using the Sodium-dependent Multivitamin Transporter (SMVT or SLC5A6). This can be inhibited by substances like biotin, indicating a shared carrier.[ref]

Role in Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, or dementia:

There are questions about whether low pantothenic acid levels in the brain play a role in neurodegenerative diseases. Studies looking at serum levels are ambiguous, but brain levels of vitamin B5 show a connection.

A 2024 study showed that in post-mortem brain samples from Lewy body dementia patients, pantothenic acid levels were significantly lower than normal in six brain regions. The brain regions with low B5 included the substantia nigra, motor cortex, visual cortex, and hippocampus – all of which are implicated in Lewy body dementia or Parkinsonian dementia.[ref]

In Alzheimer’s brains, researchers found that of 33 proteins related to mitochondrial function, only those related to CoA and pantothenic acid were altered. They also found a brain deficiency of pantothenate.[ref] Other studies also show a cerebral vitamin B5 deficiency in Alzheimer’s disease.[ref][ref] Mouse models of familial Alzheimer’s show that oral administration of pantethine prevented some symptoms and also regulated intestinal flora.[ref][ref]

In Huntington’s disease, there is also a notable pantothenate deficiency, even seen prior to symptoms developing.[ref]

What happens when coenzyme A is limited in neurons?

A 2023 study in Nature explained the metabolic cost of limited CoA in motor neurons, which have an exceptionally high energy demand. In the brain, motor neurons rely primarily on mitochondrial ATP production, and mitochondrial DNA disruption or mitochondrial energy dysfunction are at the heart of motor neuron diseases, such as ALS. Hypermetabolism can occur in the neurons in response to uncoupling in the ATP production pathway, as a way to compensate for the dysfunction. This eventually leads to a depletion of vitamin B5 and a decrease in acetyl-CoA.[ref]

What happens with rare Genetic Mutations related to vitamin B5?

Looking at the effect of rare and deleterious mutations can give us an idea of the effect of the gene. The genetic diseases are caused by two copies of mutations, but carriers of one copy may have a very mild phenotype.

PANK2 gene: encodes one of four isoforms of pantothenate kinases, specifically the one that catalyzes the rate‐limiting step in coenzyme A (CoA) biosynthesis. It is primarily found in the mitochondria. Mutations cause decreased CoA synthesis, altered lipid metabolism, and impaired iron-sulfur clustering (iron accumulation).

In people with two PANK2 mutations, a genetic disorder called Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN) occurs. It causes dystonia, meaning uncontrolled muscle movements, and symptoms similar to Parkinson’s or Parkinsonian dementia. This is due, in part, to iron accumulating in the brain, as seen on MRIs, as well as the lack of mitochondrial energy production. The classical form of PKAN occurs with an early onset in childhood, while the atypical PKAN occurs later (>10 years) and progresses more slowly.[ref][ref][ref]

PANK3 gene: encodes another pantothenate kinase, but this one is mainly found in the cytoplasm of kidney, liver, and intestinal cells. Its expression is regulated by the level of acyl-CoA.

A 2025 non-targeted metabolomics study showed that PANK3 is important in maintaining intestinal barrier function, and it is downregulated in ulcerative colitis. Upregulating PANK3 restored the intestinal epithelial barrier in mice, and folate was found to upregulate PANK3.[ref]

Clinical trials on pantothenic acid:

There are relatively few clinical trials using vitamin B5. Almost like there’s no money in it.

LDL cholesterol: A small clinical trial using pantethine (600 mg/day from weeks 1 to 8 and 900 mg/day from weeks 9 to 16) showed an 11% decrease from baseline after 16 weeks.[ref]

Rheumatoid diseases: A 2025 meta-analysis of trials involving supplemental vitamin B5 for rheumatological disease found clinical improvements for most studies, especially cutaneous lupus (skin lesions), fatigue in lupus, and pain in osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia.[ref]

Muscle performance: A small clinical trial in eight healthy young volunteers found that supplementing with 1.5g/day of pantothenic acid did not increase muscle CoA levels or improve performance.[ref]

Skin mask: A skin mask containing panthenol decreased redness and promoted skin repair after undergoing facial laser treatment.[ref]

Now let’s switch gears and look at how your genes impact vitamin B5, and then solutions for improving levels, if needed.

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics

Carnitine: Genetic Variants Affecting Mitochondrial Energy and Health

References: