Key takeaways:

- Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis, are chronic gastrointestinal disorders that are serious, life-altering diagnoses.

- Genetic variants play a big role in susceptibility to IBD, in combination with environmental factors.

- Alterations in the way the immune system interacts with the gut microbiome cause inflammation in the intestines.

- Knowing which genetic variants you have may help you figure out which lifestyle changes would be most helpful.

What is Inflammatory Bowel Disease?

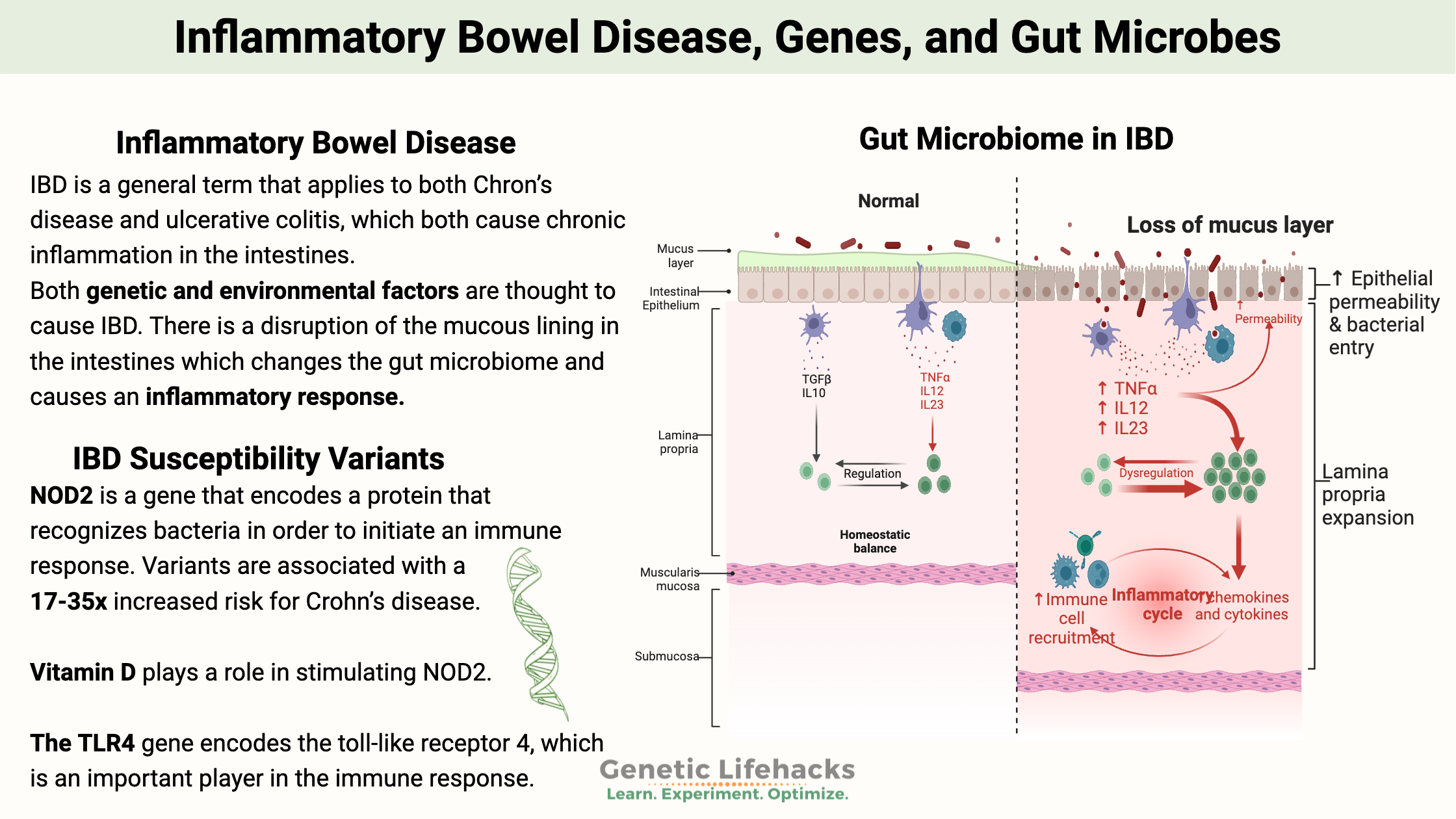

IBD (inflammatory bowel disease) is a general term that encompasses two chronic inflammatory conditions of the gastrointestinal tract: Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. [ref] These are characterized by chronic, relapsing-remitting inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract.

- Crohn’s disease can affect any part of the GI tract, but it usually affects the small intestine.

- Ulcerative colitis usually affects the colon and rectum.

The immune system seems to malfunction in IBD, causing inflammation in the GI tract. This eventually leads to the destruction of part of the intestines, causing pain, diarrhea, fever, malnutrition, and other symptoms.[ref]

Pathogenesis and Disease Mechanisms

A combination of genetic and environmental factors is thought to cause IBD. The pathophysiology of IBD involves complex interactions between multiple factors:

Immune Dysregulation:

In IBD, there is a disruption of the mucous lining in the intestines, which changes the gut microbiome and causes an inflammatory response and immune dysregulation.[ref]

Intestinal macrophages play critical roles in mucosal immunity, microbial surveillance, and tissue repair. When the gut microbiome shifts so that there are more Bacteroides fragilis, a toxin is released that modifies macrophages and promotes an inflammatory shift in the macrophages.[ref]

B Cell and T Cell Involvement:

B cells and T cells are types of white blood cells that are part of the innate immune response. IBD used to be viewed as primarily T cell-driven, but accumulating evidence demonstrates critical roles for B cells.[ref]

Environmental factors:

Diet, lifestyle, smoking, and medications can all be part of the changes in the gut. These factors are things that other people can handle, but in IBD, the combination of environmental factors, genetic vulnerability, and the gut microbiome comes together to cause inflammation.

Related article: Emulsifiers, gut mucosa, and inflammation

Histamine receptor connection:

Histamine is a biogenic amine best known for its role in allergic reactions, and high histamine levels in the gut can cause gastrointestinal distress. However, histamine also has many fundamental and important roles in the body. In healthy guts, histamine can dampen immune responses to bacteria via the histamine 2 receptor (H2R), especially on immune cells that sense bacterial products.

The results showed that people with IBD had a lower percentage of circulating monocytes expressing H2R compared with healthy controls. In the sections of the intestine with active inflammation, there were more H2 receptors than normal, but they weren’t controlling the inflammation.[ref] One takeaway from this is that H2 blockers, such as famotidine for heartburn, may be counterindicated in IBD. Talk with your doctor. [ref]

Genetic risk factors for IBD: NOD2 and more

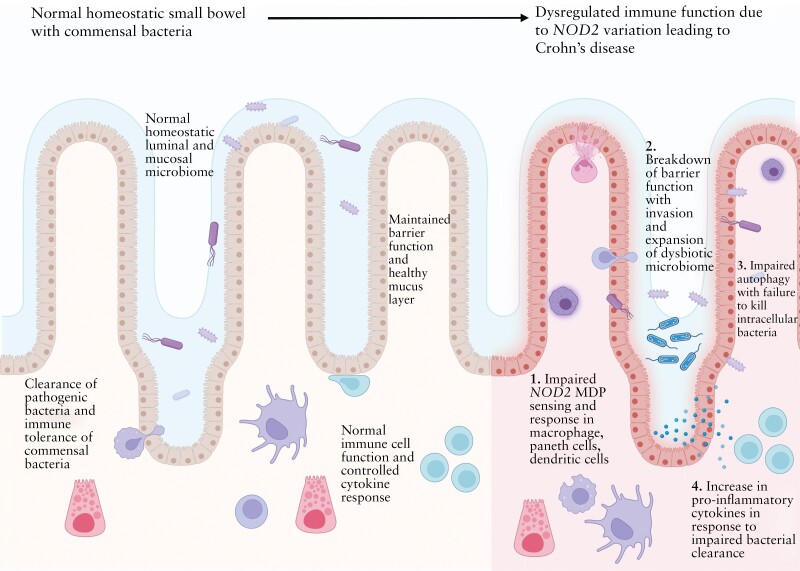

NOD2, also referred to as CARD15, is a gene that encodes a protein (nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2) that recognizes bacteria in order to initiate an immune response.[ref]

NOD2 interacts with components found on both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria found in your colon. It can also detect single-stranded RNA from viruses. Your gut microbiome interacts with your immune system in many ways. NOD2 plays an essential role in the way that the immune system keeps gut microbes in the right place and at the right levels in the colon. When encountering bacterial components, NOD2 activates the NF-κB or MAPK signaling pathways, which causes an inflammatory response that balances and keeps the microbial composition in the gut under control.[ref][ref]

When NOD2 is impaired, the gut microbiome is often not in homeostasis. There is an impaired clearance of bacteria. The loss of this regulatory factor in the intestines increases the risk of IBD.[ref]

NOD2 was first identified in genetic studies in 2001, and it is consistently found to be important in the development of IBD. When NOD2 is impaired, it results in the upregulation of alternative inflammatory pathways, including the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in the intestinal barrier.[ref]

Additional genetic risk factors for IBD:

Genes that are associated with altered gut microbiome composition are strongly tied to IBD risk. And genetic variants that alter the inflammatory response can also play a role in both the development and severity of IBD.

TLR4:

TLR4 (toll-like receptor 4) is a pattern recognition receptor that recognizes certain bacteria and promotes an inflammatory response. Levels are usually low in the intestinal barrier of healthy individuals, but it is upregulated in IBD, contributing to the inflammation. Variants that increase TLR4 are associated with an increased relative risk of IBD.[ref]

IL26:

IL-26 (interleukin-26) is a proinflammatory cytokine in the IL-10 family. It is often upregulated in the lining of the intestines in IBD. It is produced by activated T cells, especially Th17 cells, and signals for increased inflammation.[ref]

NLRP3:

The NLRP3 inflammasome is activated by cell damage or by pathogens in the gut. When activated, it triggers the production of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and IL-18. Variants in the CAIS1 gene that encode NLRP3 are associated with IBD risk.[ref]

IBD Genotype Report:

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks:

Diet and Lifestyle Actions:

Increasing short-chain fatty acids, impacting NOD2:

NOD2 can be upregulated in the intestines by butyrate.[ref] Butyrate is a short-chain fatty acid produced by certain gut bacteria and also found in small amounts in foods such as butter and other full-fat dairy. Resistant starch (found in cooked and cooled potatoes and rice) feeds the kind of bacteria that produce butyrate.

Directly supplementing with sodium butyrate was shown in a placebo-controlled clinical trial to improve quality of life and decrease inflammation in IBD patients.[ref]

Vitamin D plays a role in stimulating NOD2.[ref] Get your vitamin D levels checked to see if you have sufficient levels. Sunshine is the natural way to boost your vitamin D levels, but you can supplement vitamin D if you can’t get enough sun to boost your levels. I like the ones that are coconut oil-based.

Related article: Learn more about vitamin D.

Genetic interactions with Ergothionine:

A common food that can be a problem for some people with IBD is mushrooms, according to a study involving mainly Crohn’s patients. Ergothioneine is a compound naturally synthesized by bacteria and fungi, including culinary mushrooms (white button, shiitake, portobello, and oyster). Ergothionine is a natural antioxidant, but people with genetic variants in SLC22A4 which increase the absorption of the antioxidant. In inflammatory bowel diseases, the excess antioxidant transport can be too much, tipping the balance.[ref]

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

TNF-alpha: Inflammation, Chronic Diseases, and Genetic Susceptibility

References: