Key takeaways:

- Restless leg syndrome (RLS) and Periodic Limb Movement Disorder (PLMD) can disrupt sleep and have significant long-term effects on your health.

- Genetic variants in dopamine, inflammation, and circadian rhythm genes, such as MEIS1, BTBD9, PTPRD, MAP2K5, IL1B, and IL-17A, contribute to susceptibility.

- Animal studies shed even more light on the root causes, pointing to histamine pathways in the brain as well as dopaminergic disruption, ferroptosis, and circadian disruption.

- Lifestyle, supplements, physical interventions, or diet changes may help – tailored to your genetic susceptibility pathways.

Members will see their genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

RLS and PLMD: Science, Solutions, and Genetics

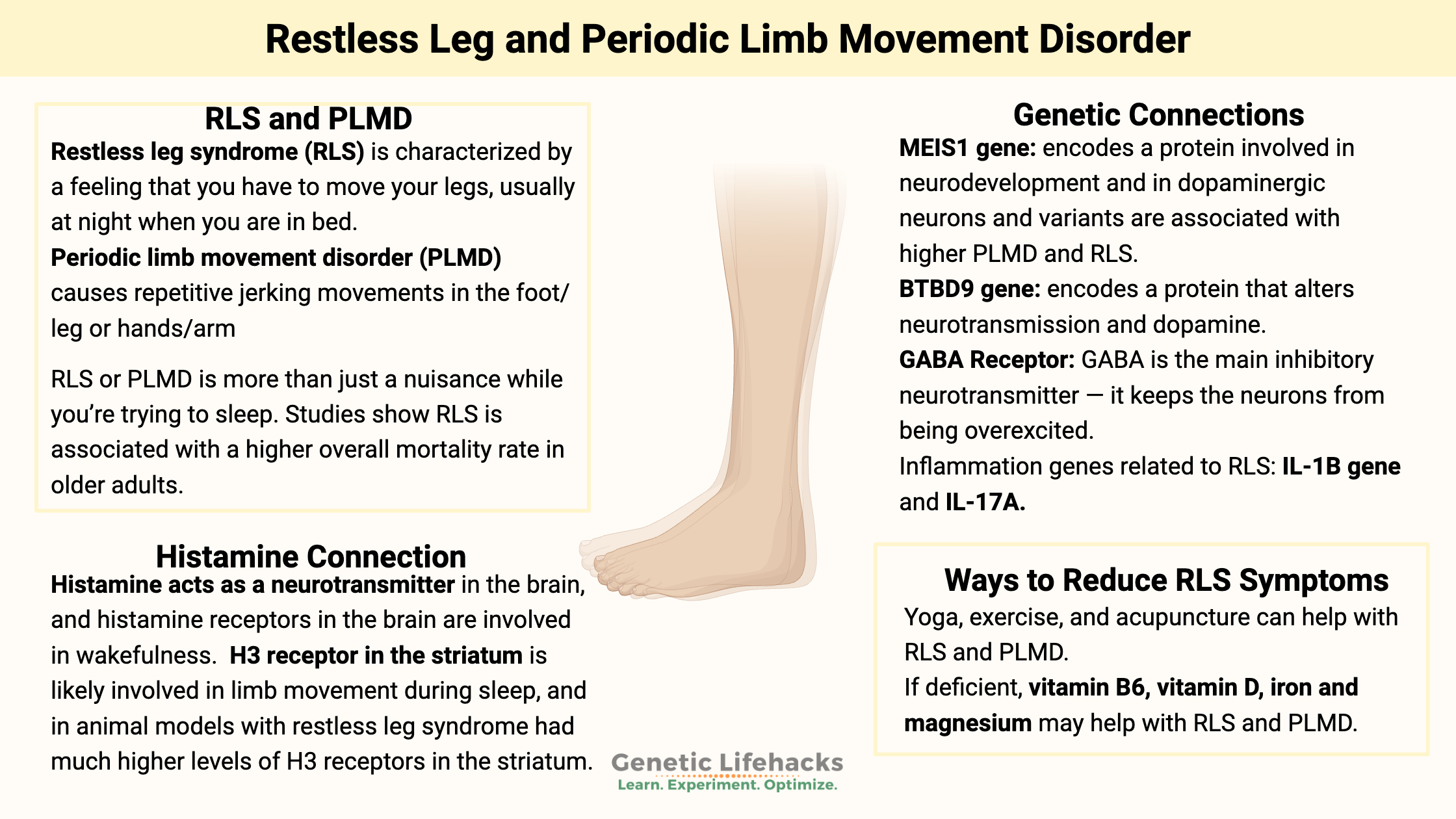

Restless leg syndrome (RLS) is characterized by a feeling that you have to move your legs, usually at night when you are in bed. In some people, it can also affect the need to move their arms. Restless leg syndrome is estimated to affect between 4 and 14% of adults. It is most prevalent in older women, but it can affect both men and women at any age.

Periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) causes repetitive jerking movements in the foot/leg or hands/arms. For some people, it is an involuntary repetitive movement, such as flapping a hand or jerking a leg, that lasts about a minute at a time.

In contrast to RLS, PLMD is more common in men than women.[ref] PLMD is also called Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep (PLMS). I’ll use PLMD here for consistency throughout the article.

Restless legs and PLMD occur together in many people, but they can also exist separately. Most research studies group the two topics together, and genetically, they may have common pathways involved.

Why is this topic important?

RLS or PLMD is more than just a nuisance while you’re trying to sleep. In a study of older men, restless leg syndrome was associated with a higher mortality rate, even after controlling for a number of other variables.[ref] PLMD is negatively correlated with REM sleep duration and is associated with poorer cognitive function in middle-aged and elderly individuals. [ref]

Underlying cause of RLS or PLMD:

Twin studies show that there is a strong genetic susceptibility to RLS, but there are also environmental factors that contribute to the risk of RLS.[ref]

There are thousands of articles and studies on restless leg syndrome, and when reading through a lot of them, a picture emerges of specific pathways – and specific genes – being important in different ways.

Here’s where we are going with this…

| Pathway | Finding/Role |

|---|---|

| Dopaminergic | MEIS1/BTBD9 influence dopamine pathways; medication treatments overlap with Parkinson’s |

| Iron, ferroptosis | Low brain iron is found in some RLS cases, but this is not necessarily due to low serum iron levels. Instead, it is disrupted iron homeostasis, with both high and low iron being a problem. |

| Circadian disruption | Underlying the night time onset of symptoms is circadian disruption, interacting with dopamine, histamine, and glutamate |

| Histamine | H3 (histamine) receptor activity in the brain (animal, some human data) |

| Inflammation | High levels of cytokines (IL1B, IL-17A) may increase risk, altered natural killer cells and high IL-13 are frequently seen. |

| Medications | SSRIs, tricyclics increase PLMD risk; benzodiazepines may decrease PLMD |

Now let’s dive into each of these in depth.

Dopaminergic pathways:

When researchers don’t really understand the cause of a disease, they often use genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to see if they can identify which genetic variants and which biological pathways are involved. It is an approach that removes any preconceived notions about why a disease occurs, but it can also sometimes provide red herrings.

GWAS identifies BTBD9 and MEIS1:

In 2007, genome-wide studies found that the BTBD9 and MEIS1 genes were associated with an increased risk of both restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder.[ref][ref] Since then, numerous studies have been conducted to replicate the findings and to find out why these two genes are so important for RLS and PLMD.

MEIS1 gene function:

The MEIS1 gene codes for a homeobox protein that is involved in turning on and off genes during development and in neurodevelopment. It is expressed in the substantia nigra – the region of the brain involved in dopamine production. MEIS1 is also thought to be involved in the formation of blood cells.[ref]

The substantia nigra is the region of the brain that causes dopamine-related issues in Parkinson’s disease. This is important in RLS and PLMD because the medications available for RLS are Parkinson’s medications. People with Parkinson’s are at an elevated risk of also having RLS.[ref][ref] Interestingly, mice with half of the normal MEIS1gene function are restless and move 16% more than normal mice. The mice weren’t anxious: they just moved more, traveled longer distances, and were a little speedier.[ref]

Other studies show that decreased MEIS1 causes changes to the cholinergic neurons in the region of the brain that controls voluntary movement (the striatum).[ref]

BTBD9 gene:

The BTBD9 gene codes for a protein involved in synaptic plasticity in the brain as well as circadian rhythm.[ref] If you delete the BTBD9 gene, it alters neurotransmission. A recent study shows that mice without the BTBD9 gene had enhanced brain activity in the striatum, which controls voluntary movement. The neurons in this area are mostly dopaminergic neurons that contain either dopamine 1 receptors or dopamine 2 receptors. The study showed that lacking BTBD9 caused enhanced activity and excitability in these dopaminergic neurons in the striatum. These mice without BTBD9 were more active when they should be resting, had disturbed sleep, and were more sensitive to temperature.[ref]

Circadian regulation of dopamine:

Brain imaging studies show that there may be an evening and nighttime dopamine deficit in the striatum due to increased daytime receptor function.[ref] There is an overall circadian rhythm to dopamine production, and it is naturally lower at night and higher during the day. The lowest levels of dopamine production are usually around 3 am, on average.[ref]

Typically, doctors treat RLS and PLMD with dopamine agonist medications that are traditionally used for Parkinson’s disease (a low-dopamine disease). These drugs are effective for some people, but they can have side effects. For example, Sinemet is a dopamine agonist that is commonly prescribed with a long list of side effects.[ref] Too much dopamine in the brain can cause psychosis, and atypical antipsychotics block dopamine receptors. It turns out that a side effect of some of the atypical antipsychotics is that they can cause or worsen RLS.[ref] This presents a picture of dopamine being important at the right level and at the right time of day.

Circadian rhythm is also inherent in the rise and fall of other neurotransmitters, including levels of histamine and glutamate, which are excitatory neurotransmitters. Interestingly, iron levels also change in neurons, rising and falling over the course of the day.[ref]

Histamine receptors in the brain and PLMD or RLS:

Histamine acts as a neurotransmitter in certain areas of the brain, and histamine receptors in the brain are involved in wakefulness. The H3 receptor is one of the histamine receptors found in the brain.

A 2020 study in an animal model of RLS showed that the H3 receptor in the striatum is likely involved in limb movement during sleep. Activating the H3 receptor with a drug increased motor activity during sleep, and blocking the H3 receptor decreased motor activity during sleep. In addition, those with restless leg syndrome had much higher levels of H3 receptors in the striatum than the normal animals[ref]

The H3 receptor in the brain regulates histamine release through a negative feedback loop. It also regulates the release of dopamine, GABA, and acetylcholine in certain areas of the brain.

If histamine is involved in RLS and PLMD, it would make sense that there would be an overlap with other disorders that involve high levels of histamine due to mast cell activation. This appears to be true. A study of patients with mast cell activation syndrome found that they were about 3 times more likely to have restless leg syndrome than a control group.[ref]

Related article: Histamine receptors, histamine intolerance

Inflammation and RLS/PLMD:

Some studies show higher inflammatory cytokines in people with RLS and/or PLMD. [ref]

A question that comes to mind is whether the inflammation caused the RLS/PLMD or whether the sleep disruption increased the inflammation. Genetic research suggests that inflammation is a possible cause, rather than a bystander.

A genetic study found that people with variants in the IL1B (interleukin 1B) and IL-17A genes have a higher risk of RLS/PLMD. IL-1β and IL-17A are inflammatory cytokines, and researchers theorize that higher levels of inflammation in the brain may affect dopamine. [ref]

A 2025 study showed that patients with RLS had higher serum IL-13 (inflammatory cytokine) levels and altered natural killer cell levels.[ref] The IL-13 connection is interesting, since IL-13 is elevated in asthma and allergies, tying back to altered histamine levels in the brain.

Related article: IL-13 genetic variants

Iron, ferroptosis, and RLS:

A number of studies suggest that low levels of iron in the brain may be a contributing factor in some people with RLS. This is based on studies showing that people with RLS are more likely to have low cerebrospinal fluid ferritin. However, most studies show that serum ferritin levels are not different in people with RLS.[ref]

Brain imaging studies:

Brain imaging, including MRI, PET, and SPECT, studies look at the brains of people with RLS. Some people (but not all) with RLS have lower iron stores, which show up on MRI scans. Many of the other studies were inconclusive or had conflicting results.

Ferroptosis and circadian rhythm:

A 2025 finding may explain some of the conflicting results. It showed that ferroptosis is upregulated in RLS. Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent form of cell death, where iron accumulates and causes lipid peroxidation to kill the cell or neuron. The study also indicated that ferroptosis was being triggered by circadian rhythm changes. The circadian clock is a cellular clock governing which genes are expressed at different times of the day. The RLS and PLMD study showed that multiple circadian rhythm-controlled genes were suppressed at night in patients, and that this circadian disruption caused increased ferroptosis in the dopaminergic neurons. The ferroptosis then increased inflammation and oxidative stress markers as part of the cascade of events.[ref]

While a lot of general advice websites may suggest taking iron for RLS, that may not be the right move. One way that researchers determine causality is to look at the opposite – in this case, higher average iron levels. Mutations in the HFE gene cause iron to be absorbed at higher levels. So researchers looked at whether HFE variants and high iron are protective against RLS. The conclusion was that the mutations that give people high iron levels do not protect against RLS.

Another question that arises is whether the relative lack of iron seen in some tests is due to more iron being used to cause cell death. It’s possible that adding more iron, for someone who already has sufficient ferritin levels, could exacerbate the issue.

Medications linked to increased risk of PLMD:

A study of patients who had undergone sleep studies for other conditions (insomnia, chronic fatigue) looked for links between medications and PLMD.

- People taking SSRIs, SNRIs, or tricyclic antidepressants were significantly more likely to have PLMD.

- On the other hand, benzodiazepine and sedative use were less likely to have PLMD.[ref] Benzodiazepines enhance GABA signaling, and GABA is the inhibitory neurotransmitter.

Nutrient interactions:

A 2025 study looked at how nutrient levels of common vitamins interacted with the risk of restless leg syndrome. The study also included genetic risk and epigenetics. The findings showed that higher folate levels increased the risk of resless leg and leg movement in sleep significantly. This is a bit counterintuitive, but important to note, especially for someone getting a lot of folic acid in fortified foods (bread, pasta, rice, tortillas). The other finding, which wasn’t as surprising, was that higher magnesium levels decrease the risk of RLS.[ref]

RLS and PLMD: Genotype Report

The following genes have been shown in research studies to increase or decrease the relative risk of restless leg syndrome and/or PLMD.

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks for Restless Leg or PLMD:

The current research on periodic limb movement and restless leg syndrome points to a combination of increased ferroptosis in dopaminergic regions of the brain, altered or depressed circadian rhythm, elevated inflammatory cytokines, and altered dopamine/GABA levels.

With multiple pathways involved, it is likely that solutions also need to be multifactoral. You may need to work on circadian rhythm, balanced dopamine, and decreased neuroinflammation – all with an eye on your iron homeostasis.

With that in mind, let’s dive into the research on ways to decrease RLS and PLMD without heavy-duty medications. For information on prescription drugs, please be sure to talk with your doctor to see what the options are, along with the risks and benefits.

Optimizing circadian rhythm:

The strong connections between circadian gene expression, ferroptosis, and dopamine regulation at night point towards circadian optimization being a pathway to address.

Your circadian rhythm is the 24-hour rhythm controlling everything from sleep to digestion to hormone and neurotransmitter oscillations. This rhythm is kept on track by the timing of light exposure as well as meal timing. Exposure to light in the blue wavelengths after the sun goes down disrupts your circadian rhythm. This was never a problem before the advent of electronics and LED lights (candle and firelight don’t contain blue wavelengths).

Give all of the following suggestions a good try for at least a week to see if it makes a difference for you.

What can you do to optimize circadian rhythm?

- Shut off bright overhead lights and turn off screens (TV, cell phone, tablets) two hours before bedtime. Read a book using a lamp with an amber-colored bulb, take a bath, wind down before bed.

- Be consistent with sleep timing.

- Sleep in a dark room, eliminating anything other than red lights. If you need a night light in the bathroom, go for one with a red bulb.

- Get out into full daylight first thing in the morning. This is the opposite side of the circadian clock and is also important.

- Be consistent with meal timing, and plan for eating your last meal three or more hours before bedtime.

Related article: Switch your iPhone to red at night

Physical Ways to Reduce RLS Symptoms:

First, let’s take a look at daily physical changes that may help to support nerve and blood flow to the limbs. While these interventions show mild reductions in symptoms, they may be a good basis to stack with several micronutrient and supplement interventions.

Increase oxygen and blood flow to the legs:

Several studies suggest that peripheral hypoxia (low oxygen in the legs and arms) is contributing to RLS and PLMD. One study found that PLMD symptoms were worsened by sleeping at high altitudes.[ref] Another study found poor endothelial function in people with RLS.[ref] Another study found lower oxygen levels just in the legs of patients with RLS.

Exercise:

Exercise may help with low oxygen levels in the legs. A recent study on a small group of patients with both restless leg and peripheral artery disease found that frequent, low-intensity exercise helped reduce symptoms.[ref] Other studies also point to exercise possibly helping with restless leg, but not being a cure-all for everyone.[ref]

Yoga:

A small study showed that yoga helps with restless leg symptoms (10 people in the study).ref]

Whole-body vibration:

A study tested whether whole-body vibration would increase blood flow. The results showed that skin blood flow in the legs did not increase — but that whole-body vibration did help with RLS.[ref]

Acupuncture:

A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of acupuncture plus gabapentin versus gabapentin alone found that sleep quality increased in people who received acupuncture with their gabapentin.[ref] Another study of acupuncture alone concluded that it ‘might help’, but the data doesn’t show much improvement.[ref]

Diet and Natural Supplements for Restless Leg and PLMD:

Low-Histamine Diet:

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Genes:

References:

Lin, Yun, et al. “Fresh Genetic Insights Into Micronutrients Influences on Restless Legs Syndrome Risk.” Food Science & Nutrition, vol. 13, no. 9, Sept. 2025, p. e70568. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.70568.

Chen, Qunshan, and Xin Men. “TLR1‐Regulated Ferroptosis Gene Decreases the Occurrence of Restless Legs Syndrome.” Brain and Behavior, vol. 15, no. 11, Nov. 2025, p. e71038. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.71038.

A Genetic Risk Factor for Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep | NEJM. (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2019, from https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa072743

Bollu, P. C., Yelam, A., & Thakkar, M. M. (2018). Sleep Medicine: Restless Legs Syndrome. Missouri Medicine, 115(4), 380–387.

Ferini-Strambi, L., Carli, G., Casoni, F., & Galbiati, A. (2018). Restless Legs Syndrome and Parkinson Disease: A Causal Relationship Between the Two Disorders? Frontiers in Neurology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.00551

Li, Y., Wang, W., Winkelman, J. W., Malhotra, A., Ma, J., & Gao, X. (2013). Prospective study of restless legs syndrome and mortality among men. Neurology, 81(1), 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e318297eee0

Rizzo, G., Li, X., Galantucci, S., Filippi, M., & Cho, Y. W. (2017). Brain imaging and networks in restless legs syndrome. Sleep Medicine, 31, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2016.07.018

Sarayloo, F., Dion, P. A., & Rouleau, G. A. (2019a). MEIS1 and Restless Legs Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. Frontiers in Neurology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00935

The Role of BTBD9 in Striatum and Restless Legs Syndrome. (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2019, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6787346/

Ylikoski, A., Martikainen, K., & Partinen, M. (2015). Parkinson’s disease and restless legs syndrome. European Neurology, 73(3–4), 212–219. https://doi.org/10.1159/000375493

Aggarwal, Shilpa, et al. “Restless Leg Syndrome Associated with Atypical Antipsychotics: Current Status, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Implications.” Current Drug Safety, vol. 10, no. 2, 2015, pp. 98–105.

Bollu, Pradeep C., et al. “Sleep Medicine: Restless Legs Syndrome.” Missouri Medicine, vol. 115, no. 4, 2018, pp. 380–87.

Connor, James R., et al. “Iron and Restless Legs Syndrome: Treatment, Genetics and Pathophysiology.” Sleep Medicine, vol. 31, 2017, pp. 61–70. PubMed, doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2016.07.028.

England, Sandra J., et al. “L-Dopa Improves Restless Legs Syndrome and Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep but Not Attention-Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder in a Double-Blind Trial in Children.” Sleep Medicine, vol. 12, no. 5, May 2011, pp. 471–77. PubMed, doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2011.01.008.

García-Martín, Elena, et al. “Missense Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Receptor Polymorphisms Are Associated with Reaction Time, Motor Time, and Ethanol Effects in Vivo.” Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, vol. 12, Jan. 2018. PubMed Central, doi:10.3389/fncel.2018.00010.

Haba-Rubio, José, et al. “Prevalence and Determinants of Periodic Limb Movements in the General Population.” Annals of Neurology, vol. 79, no. 3, Mar. 2016, pp. 464–74. PubMed, doi:10.1002/ana.24593.

Hornyak, M., et al. “Magnesium Therapy for Periodic Leg Movements-Related Insomnia and Restless Legs Syndrome: An Open Pilot Study.” Sleep, vol. 21, no. 5, Aug. 1998, pp. 501–05. PubMed, doi:10.1093/sleep/21.5.501.

Innes, Kim E., et al. “Efficacy of an Eight-Week Yoga Intervention on Symptoms of Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS): A Pilot Study.” Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine (New York, N.Y.), vol. 19, no. 6, June 2013, pp. 527–35. PubMed, doi:10.1089/acm.2012.0330.

Jiménez-Jiménez, Félix Javier, et al. “Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Receptors Genes Polymorphisms and Risk for Restless Legs Syndrome.” The Pharmacogenomics Journal, vol. 18, no. 4, 2018, pp. 565–77. PubMed, doi:10.1038/s41397-018-0023-7.

—. “Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Receptors Genes Polymorphisms and Risk for Restless Legs Syndrome.” The Pharmacogenomics Journal, vol. 18, no. 4, 2018, pp. 565–77. PubMed, doi:10.1038/s41397-018-0023-7.

Kemlink, D., et al. “Replication of Restless Legs Syndrome Loci in Three European Populations.” Journal of Medical Genetics, vol. 46, no. 5, May 2009, pp. 315–18. PubMed, doi:10.1136/jmg.2008.062992.

Kim, Min Seung, et al. “Impaired Endothelial Function May Predict Treatment Response in Restless Legs Syndrome.” Journal of Neural Transmission (Vienna, Austria: 1996), vol. 126, no. 8, Aug. 2019, pp. 1051–59. PubMed, doi:10.1007/s00702-019-02031-x.

Kokoglu, Aysenur, et al. “Immune Cells and Functions in Patients with Restless Legs Syndrome.” Immunology Letters, vol. 276, Dec. 2025, p. 107056. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imlet.2025.107056.

Lamberti, Nicola, et al. “Restless Leg Syndrome in Peripheral Artery Disease: Prevalence among Patients with Claudication and Benefits from Low-Intensity Exercise.” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 8, no. 9, Sept. 2019. PubMed Central, doi:10.3390/jcm8091403.

Lyu, Shangru, et al. “The Role of BTBD9 in Striatum and Restless Legs Syndrome.” ENeuro, vol. 6, no. 5, Oct. 2019. PubMed Central, doi:10.1523/ENEURO.0277-19.2019.

Mitchell, Ulrike H., et al. “Decreased Symptoms without Augmented Skin Blood Flow in Subjects with RLS/WED after Vibration Treatment.” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine: JCSM: Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, vol. 12, no. 7, 15 2016, pp. 947–52. PubMed, doi:10.5664/jcsm.5920.

Moore, Hyatt, et al. “Periodic Leg Movements during Sleep Are Associated with Polymorphisms in BTBD9, TOX3/BC034767, MEIS1, MAP2K5/SKOR1, and PTPRD.” Sleep, vol. 37, no. 9, Sept. 2014, pp. 1535–42. PubMed Central, doi:10.5665/sleep.4006.

—. “Periodic Leg Movements during Sleep Are Associated with Polymorphisms in BTBD9, TOX3/BC034767, MEIS1, MAP2K5/SKOR1, and PTPRD.” Sleep, vol. 37, no. 9, Sept. 2014, pp. 1535–42. PubMed Central, doi:10.5665/sleep.4006.

—. “Periodic Leg Movements during Sleep Are Associated with Polymorphisms in BTBD9, TOX3/BC034767, MEIS1, MAP2K5/SKOR1, and PTPRD.” Sleep, vol. 37, no. 9, Sept. 2014, pp. 1535–42. PubMed, doi:10.5665/sleep.4006.

—. “Periodic Leg Movements during Sleep Are Associated with Polymorphisms in BTBD9, TOX3/BC034767, MEIS1, MAP2K5/SKOR1, and PTPRD.” Sleep, vol. 37, no. 9, Sept. 2014, pp. 1535–42. PubMed Central, doi:10.5665/sleep.4006.

Raissi, Gholam Reza, et al. “Evaluation of Acupuncture in the Treatment of Restless Legs Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian Studies, vol. 10, no. 5, Oct. 2017, pp. 346–50. PubMed, doi:10.1016/j.jams.2017.08.004.

Rizzo, Giovanni, et al. “Brain Imaging and Networks in Restless Legs Syndrome.” Sleep Medicine, vol. 31, Mar. 2017, pp. 39–48. PubMed Central, doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2016.07.018.

Sarayloo, Faezeh, et al. “MEIS1 and Restless Legs Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review.” Frontiers in Neurology, vol. 10, Aug. 2019. PubMed Central, doi:10.3389/fneur.2019.00935.

—. “MEIS1 and Restless Legs Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review.” Frontiers in Neurology, vol. 10, Aug. 2019. PubMed Central, doi:10.3389/fneur.2019.00935.

—. “MEIS1 and Restless Legs Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review.” Frontiers in Neurology, vol. 10, Aug. 2019. PubMed Central, doi:10.3389/fneur.2019.00935.

Song, Yuan-Yuan, et al. “Effects of Exercise Training on Restless Legs Syndrome, Depression, Sleep Quality, and Fatigue Among Hemodialysis Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, vol. 55, no. 4, 2018, pp. 1184–95. PubMed, doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.12.472.

Stefani, Ambra, et al. “Influence of High Altitude on Periodic Leg Movements during Sleep in Individuals with Restless Legs Syndrome and Healthy Controls: A Pilot Study.” Sleep Medicine, vol. 29, Jan. 2017, pp. 88–89. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2016.06.037.

Stefansson, Hreinn, et al. “A Genetic Risk Factor for Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 357, no. 7, Aug. 2007, pp. 639–47. PubMed, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa072743.

Tang, Mingyang, et al. “Circadian Rhythm in Restless Legs Syndrome.” Frontiers in Neurology, vol. 14, Feb. 2023, p. 1105463. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1105463.

—. “A Genetic Risk Factor for Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 357, no. 7, Aug. 2007, pp. 639–47. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa072743.

Thireau, Jérôme, et al. “MEIS1 Variant as a Determinant of Autonomic Imbalance in Restless Legs Syndrome.” Scientific Reports, vol. 7, 20 2017, p. 46620. PubMed, doi:10.1038/srep46620.

Trenkwalder, C., et al. “L-Dopa Therapy of Uremic and Idiopathic Restless Legs Syndrome: A Double-Blind, Crossover Trial.” Sleep, vol. 18, no. 8, Oct. 1995, pp. 681–88. PubMed, doi:10.1093/sleep/18.8.681.

Winkelmann, Juliane, et al. “Genome-Wide Association Study of Restless Legs Syndrome Identifies Common Variants in Three Genomic Regions.” Nature Genetics, vol. 39, no. 8, Aug. 2007, pp. 1000–06. PubMed, doi:10.1038/ng2099.

Xiong, Lan, et al. “MEIS1 Intronic Risk Haplotype Associated with Restless Legs Syndrome Affects Its MRNA and Protein Expression Levels.” Human Molecular Genetics, vol. 18, no. 6, Mar. 2009, pp. 1065–74. PubMed Central, doi:10.1093/hmg/ddn443.

Yang, Qinbo, et al. “Family-Based and Population-Based Association Studies Validate PTPRD as a Risk Factor for Restless Legs Syndrome.” Movement Disorders : Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society, vol. 26, no. 3, Feb. 2011, pp. 516–19. PubMed Central, doi:10.1002/mds.23459.