Don’t you hate it when the solution to a health problem works for everyone else but not you? The FODMAPs diet is a great IBS diet — for many people. But your genes make you unique, and your IBS issue may not have the same root cause as others.

This article digs into the research on how genetic variants that decrease a specific digestive enzyme can cause IBS. Included are links to check your genetic data to see if this could apply to you.

What if a low FODMAPs diet doesn’t work?

The low FODMAPs diet is often recommended as a starting point for anyone with gas, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, and other symptoms of IBS. Often people describe the diet in such a way that you think it has to be the only solution for everyone — people absolutely swear by it, there are Facebook groups for support, and many doctors recommend it as a place to start for IBS symptoms.

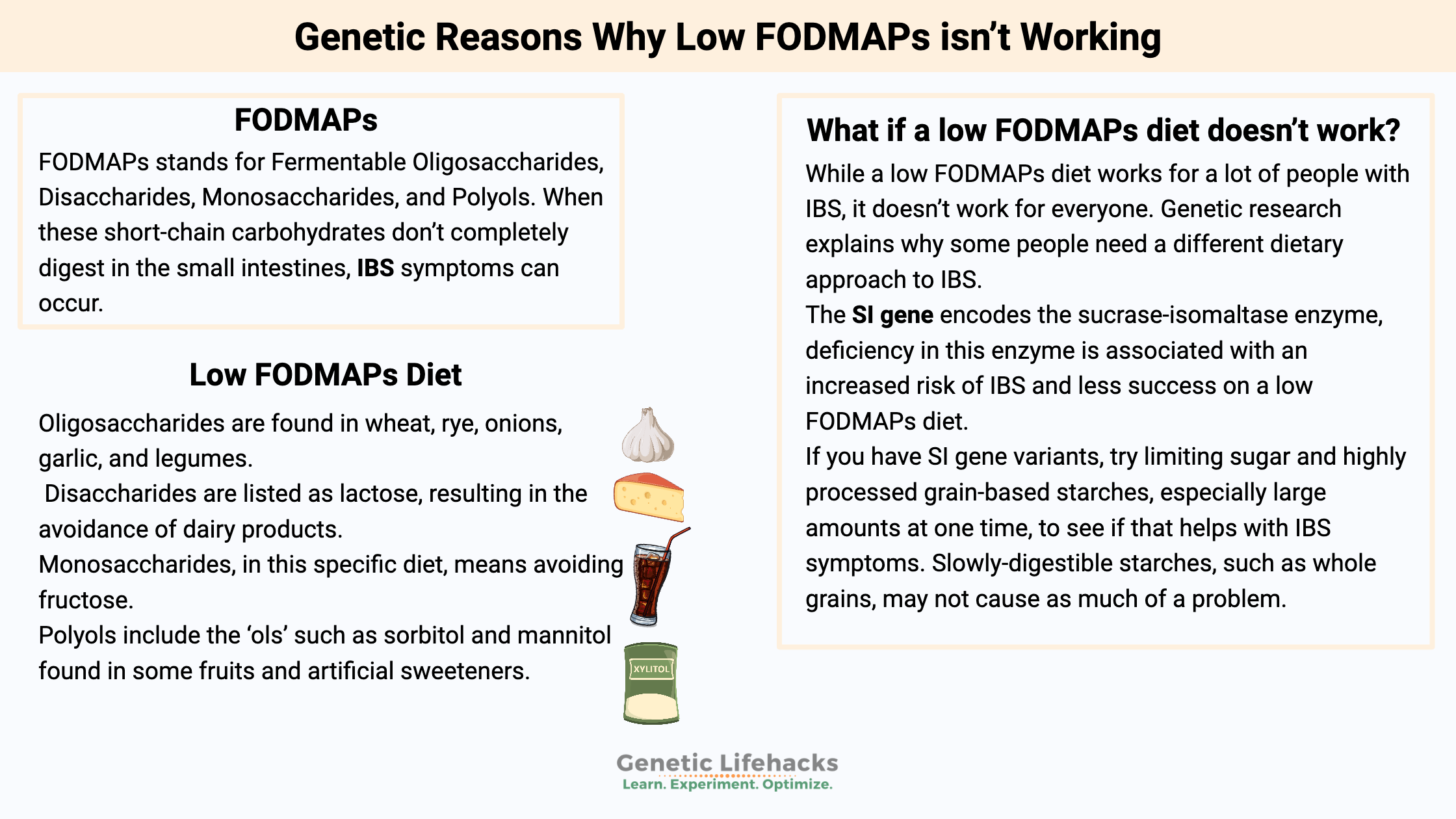

While a low FODMAPs diet works for a lot of people with IBS, it doesn’t work for everyone. Genetic research explains why some people need a different dietary approach to IBS.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) has multiple causes, and a one-size-fits-all dietary solution is unlikely to work for everyone.

What are FODMAPs?

FODMAPs stands for Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols. When these short-chain carbohydrates don’t completely digest in the small intestines, IBS symptoms can occur. Bacteria in the large intestines can ferment undigested carbohydrates, causing bloating and other problems.

Let’s break down the low FODMAPs diet with some examples:

Oligosaccharides are fructans and GOS (galactooligosaccharides). They are found in wheat, rye, onions, garlic, and legumes. Disaccharides are listed as lactose, resulting in the avoidance of dairy products. Monosaccharides, in this specific diet, means avoiding fructose, while polyols include the ‘ols’ such as sorbitol and mannitol found in some fruits and artificial sweeteners.[ref]

The low FODMAPs diet cuts out many of the IBS problem foods, such as those including lactose or fructose, so it works for a lot of people.

But what if the specific FODMAPs carbohydrates aren’t your problem? It turns out that there are multiple causes of not being able to break down foods. You could be a champ at digesting lactose, and fructose could be fine for you…

Another cause of IBS: is decreased sucrase-isomaltase

Researchers have found that SI insufficiency is one cause of irritable bowel syndrome.

SI stands for the sucrase-isomaltase enzyme produced in the small intestines to break down sugar and starches. Sucrase is the enzyme for breaking down sucrose (e.g., table sugar). Isomaltase breaks down maltose, which is a disaccharide from grains and starches.

Congenital sucrase-isomaltase deficiency (CSID) is an uncommon genetic disease caused by severe mutations in the SI gene. Usually diagnosed in infants when they start eating solid foods or drinking fruit juices, the severe deficiency of sucrase-isomaltase is a serious issue that causes babies to have bloating, pain, and watery diarrhea.

CSID, an autosomal recessive genetic disease, means two copies of a non-functioning mutation in the gene are required. It’s the worst-case scenario, and kids diagnosed with it are on a sugar and starch-restricted diet throughout childhood. CSID can improve somewhat as kids get older and their small intestine grows.

The prevalence of CSID varies by population group, with up to 1 in 500 Caucasian affected. Rates are lower in people of African descent, but indigenous populations of Alaska, Canada, and Greenland have higher rates of up to 1 in 10 with CSID.[ref]

Breaking down starches:

Sucrase-isomaltase is a dual-function enzyme, breaking down sucrose into glucose and fructose, as well as breaking certain starches into glucose.

It’s fairly easy to figure out which foods have sucrase in them — sweet fruits and anything with added sugar.

But the ‘isomaltase’ component of SI is slightly more complicated.

When you eat foods that contain starch, digestion begins in the mouth with salivary amylase (an enzyme for breaking down starch). Not all starch breaks down in the mouth, of course. Also, the pancreas secretes amylase into the small intestines to break apart starch molecules there. The broken-down starch molecules then need to undergo one more enzymatic reaction to turn them into simple sugars for absorption. The sucrase-isomaltase enzyme handles about 60-80% of starch digestion in the small intestines. The other 20-40% breaks down by another enzyme called maltase-glucoamylase.[ref]

What happens with partial sucrase-isomaltase deficiency?

It turns out that people with genetic variants or single mutations that decrease the sucrase-isomaltase enzyme are quite a bit more likely to be diagnosed with IBS.[ref][ref] A decreased production of the sucrase-isomaltase enzyme can combine with a diet high in starch or sugar to cause gas, bloating, diarrhea, and/or constipation.

Thus, for someone whose IBS is caused by low SI enzyme function, going on a low FODMAP diet may not be the whole solution.

Yes, a low FODMAP diet cuts down on some foods with starches and may give some relief, but a more tailored diet that slows the influx of sugar and starch may be a better option.

Research shows this to be true. A recent study in the British Medical Journal showed that IBS patients who carry SI gene variants are less likely to achieve IBS remission on the FODMAPs diet.[ref]

FODMAPs Diet Genotype Report:

Lifehacks:

While there are multiple causes of IBS, if you have a genetic variant that reduces sucrase-isomaltase, your best bet is to reduce your consumption of sucrose and starch to see if that improves your IBS.

Related Articles and Topics:

Problems with IBS? Personalized solutions based on your genes

There are multiple causes of IBS, and genetics can play a role in IBS symptoms. Pinpointing your cause can help you to figure out your solution.

FUT2: Are you a non-secretor of your blood type?

People with a variant in the FUT2 gene do not secrete their blood type. This affects the gut microbiome – and makes you immune to the norovirus.

Choline – Should you eat more?

An essential nutrient, your need for choline from foods is greatly influenced by your genes. Find out whether you should be adding more choline into your diet.

Folate & MTHFR

The MTHFR gene codes for a key enzyme in the folate cycle. MTHFR variants can decrease the conversion to methyl folate.