Key takeaways:

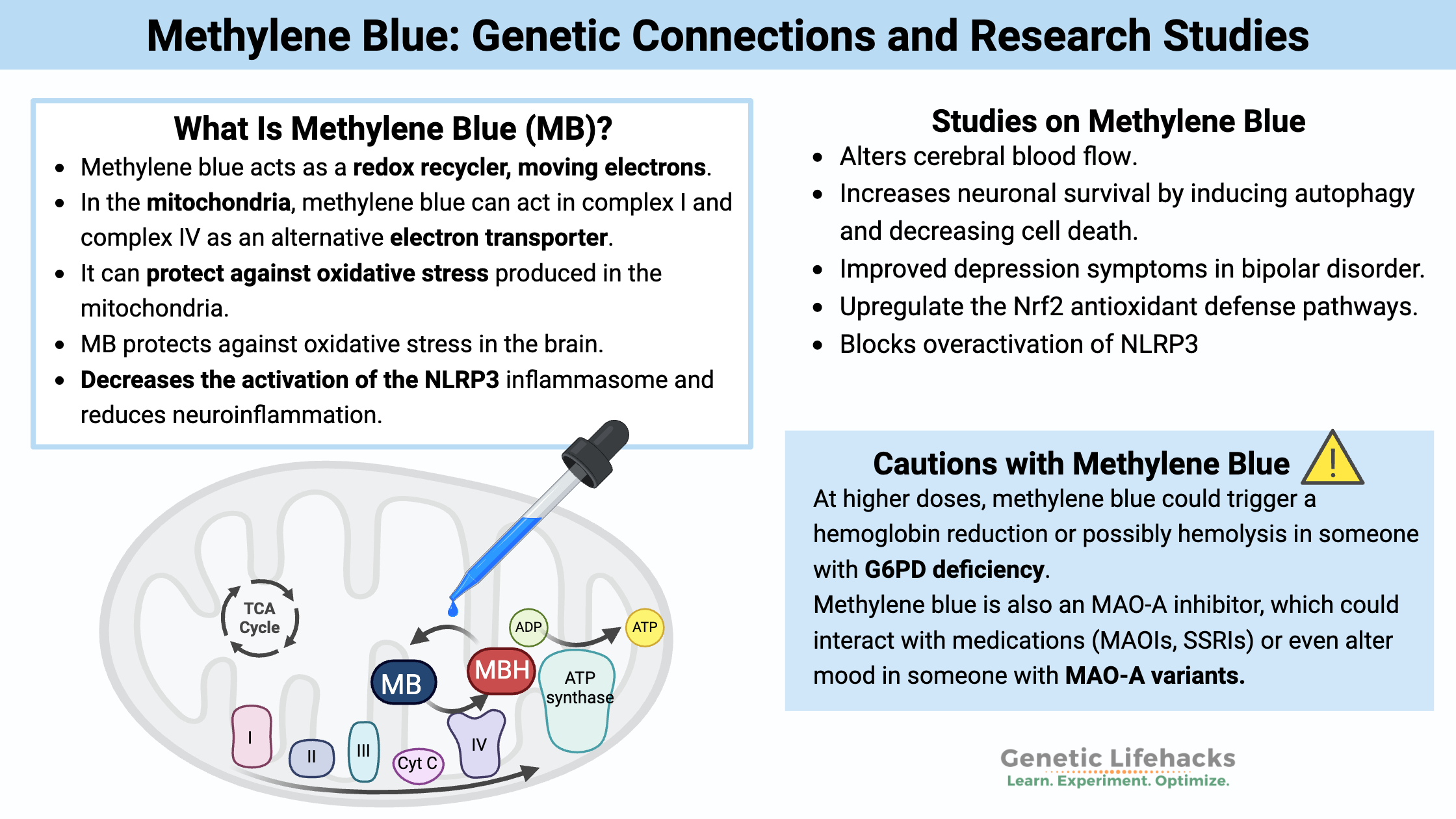

~ Methylene blue is a unique chemical that acts as a redox agent influencing mitochondrial energy production, neurotransmitter metabolism, and inflammatory pathways.

~ Studies show that it holds potential for Alzheimer’s and neurodegenerative diseases by enhancing neuronal energy and reducing oxidative stress.

~ Methylene blue also has antiviral properties and is a sensitizer for photobiomodulation.

~ Genetic variants in G6PD and MAOA may interact with methylene blue, which means some people should use caution or avoid MB.

Methylene Blue: Background Science

Methylene blue was first developed as a textile dye but was quickly found to be very useful for staining cells under the microscope. Early medical uses included the use of methylene blue to treat malaria.

In larger amounts, methylene blue turns urine a blue color, so doctors added it to psychiatric medications in order to see if the patient was compliant with taking the medication. This led to the discovery that methylene blue itself had antipsychotic effects by inhibiting MAO-A.[ref]

Currently, methylene blue is used primarily as a medication for methemoglobinemia and during certain types of heart surgery to increase oxygenation of the blood. It is also used in periodontal health combined with phototherapy.

As a drug, methylene blue is also known as methylthioninium chloride. In a clinical capacity, it is used for exposure to certain drugs or environmental toxins such as nitrates, carbon monoxide, or cyanide. It is also sometimes still used to treat malaria. [ref]

What does methylene blue do?

- Methylene blue acts as a redox recycler, moving electrons.

- In the mitochondria, methylene blue can act in complex I and complex IV as an alternative electron transporter.

- It can protect against oxidative stress produced in the mitochondria.[ref]

- Methylene blue easily crosses the blood-brain barrier, which allows methylene blue to protect against oxidative stress in the brain.

- At low concentrations, methylene blue inhibits viral replication in some viruses.[ref]

- Research also shows that methylene blue decreases activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and reduces neuroinflammation.[ref]

We will dig into all of this and more, but first, a word of caution…

Cautions with methylene blue:

Before I go any further, I want to give a heads-up that methylene blue is not something that everyone should use.

- At higher doses, methylene blue could trigger a hemoglobin reduction or possibly hemolysis in someone with G6PD deficiency.[ref]

- Methylene blue is also an MAO-A inhibitor, which could interact with medications (MAOIs, SSRIs) or even alter mood in someone with MAO-A variants.[ref]

- If you are taking SSRIs, methylene blue at higher doses increases the risk of serotonin syndrome, which can be life-threatening.[ref]

- Anyone pregnant or nursing should not use methylene blue.[ref]

In the Genotype Report section below, I’ll include the more common G6PD mutations as well as MAO-A variants to consider.

In general, if you have questions about whether a supplement or dietary change is right for you, talk to your doctor. If you are taking prescription medications, talk to your doctor and pharmacist (pharmacists are very knowledgeable about drug interactions).

How does Methylene Blue (MB) work?

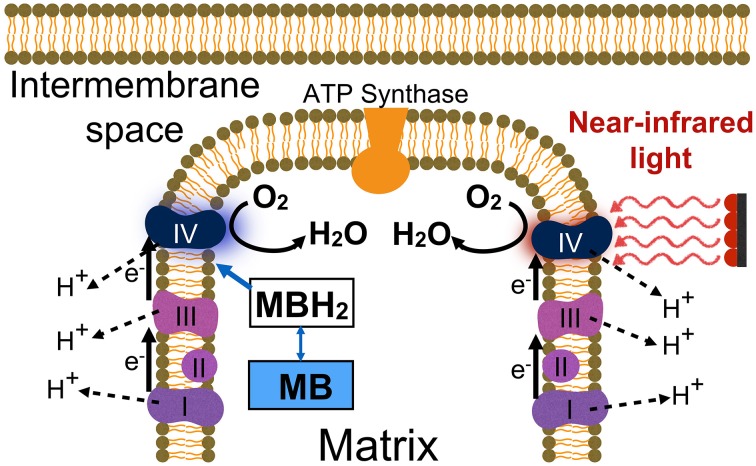

Redox (oxidation-reduction) reactions are at the heart of many of the biochemical processes that take place in our cells. Methylene Blue (MB) is unique in that it can accept electrons and also transfer electrons to oxygen to form water.

Why is this important? In mitochondria, the electron transport chain is responsible for producing ATP, which is used for cellular energy. Within the electron transport chain, at low doses, MB can act as an artificial electron donor.[ref] It receives electrons from NADH through complex I in the electron transport chain which converts it to leucomethylene blue. Leucomethylene blue then directly transfers these electrons to cytochrome c, which reoxidizes it to methylene blue in the process.[ref]

Methylene blue’s action in the cells can go beyond its role in acting as an electron acceptor (reducing ROS) and donor (boosting mitochondrial ATP production).

1) In the brain: Methylene blue can cross the blood-brain barrier. This uniquely allows it to increase mitochondrial energy, decrease oxidative stress, and decrease neuronal inflammation in the brain.

2) MAOA Inhibitor: MB inhibits nitric oxide formation and MAO-A. Monoamine oxidase (MAOA) is an enzyme involved in the metabolism of neurotransmitters, so altering MAO levels can have an anti-depressive effect on some people.[ref][ref]

Related article: MAO-A and MAO-B: Neurotransmitter levels, genetics, and studies

3) Alzheimer’s studies: In animal studies, methylene blue shows efficacy in Alzheimer’s disease. Human clinical trials are currently determining the dose.

4) Viral replication inhibitor: Studies show that MB has antiviral properties against swine flu, SARS-CoV-2, and HPV (common warts).

5) Photobiomodulation: Methylene blue is used as a photosensitizer.

6) Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory: Methylene blue acts as an antioxidant by upregulating the Nrf2 antioxidant response pathway. MB has strong anti-inflammatory properties through downregulation of NLRP3.[ref]

Let’s look at all of these in more detail:

1) Methylene blue in the brain:

The blood-brain barrier keeps many drugs and toxins out of the brain. Not only can methylene blue cross the blood-brain barrier, but it preferentially accumulates in the brain from the bloodstream.[ref]

Methylene blue has multiple effects on the brain:

An fMRI study found that methylene blue alters cerebral blood flow. The randomized controlled trial found that methylene blue increased resting-state functional connectivity in areas of the brain associated with perception and memory.[ref]

Another brain MRI study showed that MB (280 mg) increased response during vigilance tasks. The results also showed a 7% increase in correct responses to memory tests. The study participants were adults aged 22-62. [ref]

Methylene blue prevents neurological damage. A study showed that the chemotherapy drug cisplatin impairs learning due to inflammation and mitochondrial damage in the brain. The study found that MB could prevent memory impairment (in animals).[ref] Other studies point to the role of mitochondrial energy and reduction in oxidative stress as being the primary benefits of neuroprotection. Again, this is mainly shown in animal studies, but the results suggest neuroprotective effects of MB in many neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and stroke.[ref]

In animal studies of brain injury, methylene blue increases neuronal survival by inducing autophagy and decreasing cell death.[ref] MB has been studied extensively to try to determine how it protects the brain in ischemic stroke injuries.[ref] A new study in animals shows that methylene blue downregulates aquaporin 4, which is a key receptor that controls exchange across the blood-brain barrier. This downregulation prevents edema in stroke. In addition, methylene blue inhibits metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 in an animal model of stroke. [ref][ref]

Related article: Glutamate receptor genetic variants

In animals, methylene blue has anticonvulsant effects in seizure models. One type of seizure that MB protects against is that induced by kainic acid, which binds to a specific type of glutamate receptor.[ref][ref]

Methylene blue also acts on the nitric oxide-cGMP pathway. This is another way in which it has potential as an anticonvulsant.[ref]

2) Mood and neurotransmitter levels: MAOA and More

Methylene blue acts as an MAO-A inhibitor, which may decrease depressive symptoms in some people.

A double-blind crossover study of 15 mg methylene blue in bipolar patients showed that it improved depression symptoms.[ref]

Methylene blue not only acts as an MAO-A inhibitor, but it also inhibits the GABA-A receptor. GABA is the inhibitory neurotransmitter, and the GABA-A receptor receives the inhibitory signal.[ref][ref] Inhibiting the GABA-A receptor is being researched for alcohol withdrawal symptoms.[ref]

Related article: MAO-A and MAO-B SNPs

In addition, methylene blue MB is a non-selective inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase, which can affect neurotransmitter levels in the brain.[ref] Methylene blue acts on the nitric oxide-cGMP pathway. This is another way that it has potential as an anti-seizure medication as well as implications for bipolar disorder.[ref][ref]

3) Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials involving MB:

Mitochondrial dysfunction is thought to play a role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Methylene blue can reduce the production of free radicals in the brain’s mitochondria, and animal studies show that MB may be helpful in preventing Alzheimer’s disease.[ref][ref]

An initial phase III clinical trial with no benefit:

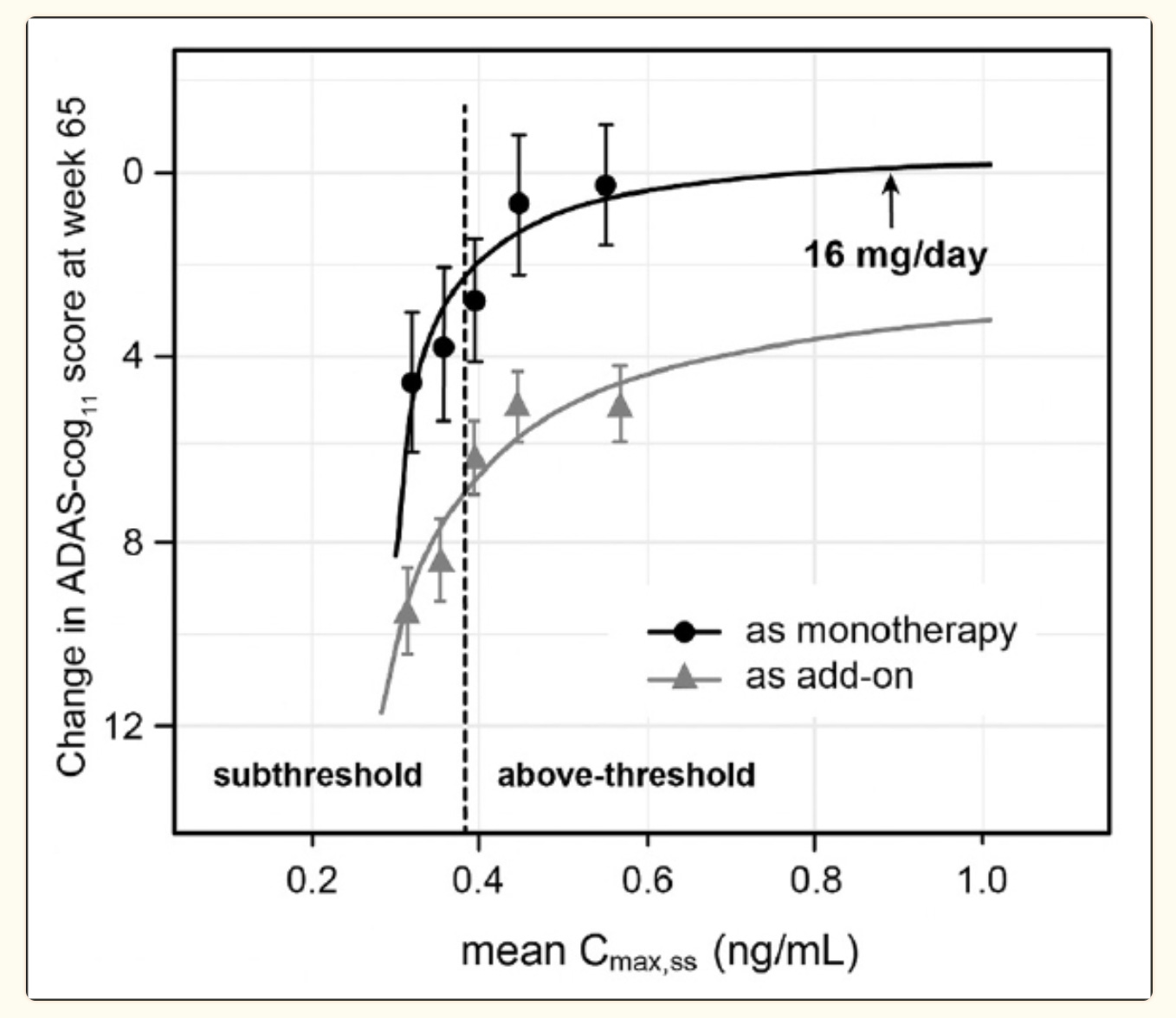

A phase III clinical trial using a stabilized, reduced form of methylene blue tested the benefits in people with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. The participants were divided into three groups: 75mg of MB twice a day, 125 mg twice a day, or a control group taking 4 mg twice a day. The results showed that there were no treatment benefits from 75mg or 125 mg when compared to a control group, which was taking 4mg of methylene blue.[ref]

A revised analysis of the Alzheimer’s trial data found that the 4mg/ twice per day dose that was used as the control group may be beneficial, especially as add-on therapy with other Alzheimer’s drugs.[ref]

The realization that the dose may be key:

Another randomized clinical trial used a 200mg/day MB dose as the active arm and an 8mg/day MB dose for the control group. While no treatment benefit was seen at 200mg/day, there were significant improvements in brain atrophy with the 8mg/day dose showing that it was likely beneficial.[ref] A 2020 analysis found that somewhere between 8- 16mg/day is likely the sweet spot for people who have mild to moderate Alzheimer’s.[ref] Clinical trials are still underway.[ref]

Related article: APOE and Alzheimer’s risk

4) Antimicrobial properties:

Methylene blue has long been known to have some antiviral activity. It corrupts the integrity of viral DNA or RNA, which gives it broad-spectrum antiviral properties. MB combined with light is also used for viral and bacterial inactivation for specific microbes.[ref][ref][ref] It’s also very commonly used as an antifungal in fish aquariums.

- At low concentrations, methylene blue inhibits the replication of H1N1 (flu virus) and SARS-CoV-2.[ref]

- Both in vitro and in vivo studies showed that methylene blue can inhibit viral growth and replication in the Zika virus.[ref]

- When combined with 635nm light, MB can decrease P. aeruginosa, an antibiotic-resistant bacteria, levels significantly.

- Methylene blue was shown early on in the COVID-19 pandemic to stop the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in cell studies.[ref] Further studies show that methylene blue prevents the spike protein on the SARS-CoV-2 virus from binding to the ACE2 receptor.[ref]

- In COVID patients, methylene blue improved blood oxygen levels, decreased hospitalization days, and decreased mortality.[ref][ref]

- For warts (human papillomavirus), a 10% MB topical gel combined with daylight photodynamic therapy (full spectrum light) provides a very good or excellent response in almost 90% of participants.

5) Photobiomodulation

I’ve mentioned several times that methylene blue is used with various forms of light therapy for antimicrobial purposes. In the 1970s, it was discovered that a 0.1% methylene blue topical treatment – along with 20 minutes of sunlight – could significantly reduce herpes outbreaks.[ref]

Methylene blue is used as a photosensitizer. It can absorb light in the red to near-infrared end of the light spectrum (max at 664 nm) and give off ROS. In photodynamic therapy, the combination of methylene blue plus red light in the 630-670 nm range generates singlet oxygen or ROS. Methylene blue tends to accumulate in tumor tissue and inflamed or infected areas. So methylene blue as a photosensitizer is being used in clinical trials to combat periodontal disease and certain types of tumors.[ref]

Light in the red to near-infrared frequencies can increase mitochondrial energy production through the absorption of a photon.

Light therapy with near-infrared light increases cytochrome oxidase, which is important in how mitochondria produce ATP. Researchers think that combining red/near-infrared light (increasing cytochrome oxidase) along with low-dose methylene blue (acting as an electron cycler in the mitochondria) is beneficial.[ref]

Related article: Photobiomodulation

6) Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory

Methylene blue has also been shown to upregulate the Nrf2 antioxidant defense pathways.[ref] The Nrf2 pathway is one way that the body uses to defend against oxidative stress by increasing the production of antioxidants. Nrf2 is a transcription factor that upregulates NQO1 and well as interacting with NLRP3.[ref]

Related article: Nrf2 pathway genes

Research also shows that methylene blue decreases the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and reduces neuroinflammation.[ref] Methylene blue’s neuroprotective effects are, at least in part, via inhibition of NLRP3 activation in the microglia.[ref][ref]

The NLRP3 inflammasome detects danger signals – damaged cells, pathogens, and toxins – and ramps up the inflammatory response. This is necessary and good in the right amount, but excess NLRP3 inflammasome activation can cause excess inflammation and promote chronic inflammatory conditions.

Related article: NLRP3 Inflammasome

Let’s shift gears and look at a few of the genetic interactions (and cautions) with methylene blue.

Methylene Blue: Genotype Report

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks: Dosing, Safety, and Response Curves

If you have any questions about methylene blue – or any supplement – talk with your doctor or pharmacist. There are serious interactions with many different medications, depending on the dose of MB.

Please don’t take this section as a recommendation as to whether you should or should not take MB. Everyone is unique, and I’m assuming that you’re reading this to gather information and make informed decisions.

Response curve

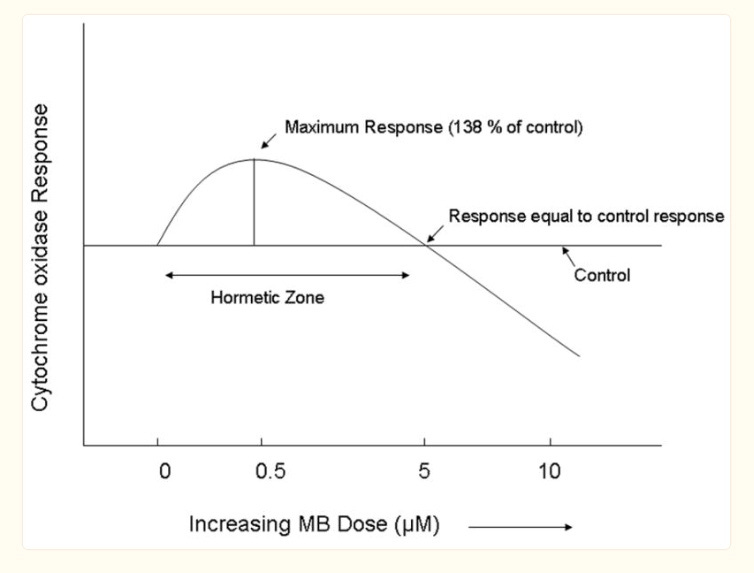

More is not always better. With methylene blue, the dose matters quite a bit. Doses that range from 0.5 – 4 mg/kg seem to have positive benefits in studies, but going above 10mg/kg decreases the biochemical response. At higher doses, methylene blue can take away electrons in the electron transport chain — slightly reducing energy production in the mitochondria.[ref]

Another clinical trial for Alzheimer’s prevention is using 8 and 16mg/day as the intervention, compared to a placebo that doesn’t contain MB.[ref] That study protocol included this graph (below) on the level of MB thought to be needed for positive results.[ref]

Sources of MB:

Methylene blue is available at the pet store to treat fish fungal diseases, but it isn’t guaranteed to be pure and could have heavy metal contamination. Instead, pharmaceutical-grade methylene blue is what to look for. You can buy it at health food or supplement stores or on online (Amazon and other places).

Look for “USP grade” which is made for human consumption. It usually comes in a glass bottle with an eye dropper. A 1% solution will provide 0.5 mg of methylene blue per drop.

Dosing:

Clinical trial dosing covers a wide range.

High dose examples under a doctor’s supervision:

- In a trial of bipolar patients, the placebo group got a 15 mg/day dose, and the active group received 195 mg/day.[ref]

- In the MRI brain study, the participants received a dose of 4mg/kg (average weight of 70 kg = 280mg). This dosage showed improvements in memory tests and changes in the brain fMRIs.[ref]

- A study involving adults with claustrophobia used a dose of 260 mg of methylene blue. The results showed methylene blue helped with the retention of cognitive training.[ref]

Low doses may have different effects:

Alzheimer’s clinical trials are looking at doses of 4 – 16 mg/day.

Online forums and nootropics websites often recommend very low doses in the range of 0.5 mg per day for cognitive benefits.

Low cellular concentrations of methylene blue allow it to be at an equilibrium and move electrons between its oxidized and reduced forms.[ref] It is likely that individual genetic variants, including MAOA and GABA-A, are involved in the right dose for an individual.

Getting Rid of Methylene Blue Stains:

Methylene blue stains anything it touches, so be careful not to stain your countertop or sink. Vitamin C may help to remove the stain. Powdered vitamin C is available on Amazon and at health food stores.

Safety and precautions:

In addition to the caution around G6PD deficiency, at higher doses, methylene blue may inhibit MAOA, which is the enzyme that breaks down neurotransmitters such as serotonin. High levels of serotonin can make you sick and possibly result in death. There are a few case studies of methylene blue being used in hospital settings (IV doses) that resulted in serotonin syndrome.[ref]

The FDA warns that methylene blue may interact with psychiatric medications. Talk with your prescribing physician before using methylene blue if you are on any medication that affects serotonin levels.

Drug interactions:

The Mayo Clinic has a long list of medications that can interact with methylene blue when given by IV. Drugs.com also has a long list of possible medication interactions. Again, please be sure to talk with your doctor and pharmacist if you are on any prescription medications. The drug interactions may be at certain dosages of methylene blue, so be sure to be specific with your questions on drug interactions.

Turning blue:

MB at higher levels will change your urine color to greenish or blue. Long-term usage at high doses (e.g. malaria treatment) can cause urine, skin, and the whites of the eyes to become bluish.[ref]

Related Articles and Topics:

Lithium Orotate and Vitamin B12: Benefits for Mood and Cognitive Support

Resveratrol: Studies, Genetic Interactions, and Bioavailability

References: