Key takeaways:

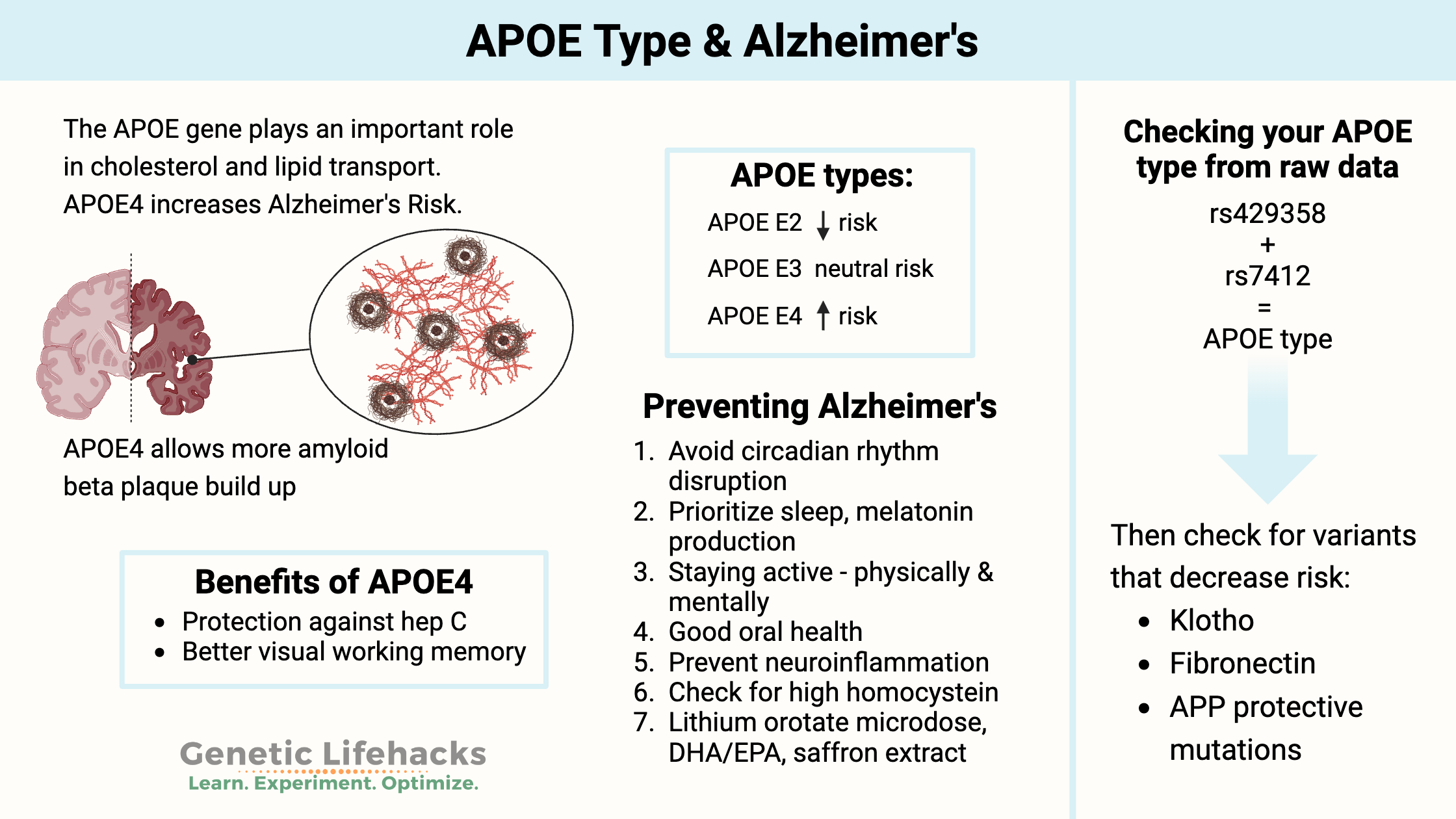

~ The APOE alleles are important in understanding your Alzheimer’s risk, and the data is found in your 23andMe raw data file (if you want to know).

~ APOE is involved in carrying cholesterol and other fats in your bloodstream, and a common variant of the gene is strongly linked to a higher risk of Alzheimer’s.[ref]

~ Alzheimer’s risk is influenced both by genes and environmental factors. Genes are only one part of the equation for Alzheimer’s.

~ Knowing your risk can help you prioritize lifestyle changes for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease.

APOE Gene Variants:

Your APOE type is defined as a combination of three different alleles (ε2, ε3, or ε4), and you will have one APOE allele from each parent.

The NIH website explains:

- APOE ε2 is not very common and is associated with a decreased risk of Alzheimer’s.

- APOE ε3 is the most common allele and neither increases nor decreases the risk of Alzheimer’s.

- APOE ε4 is found in about 15% of the population and increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. About 40% of people with Alzheimer’s carry this allele.

What does APOE do?

APOE plays a critical role in the metabolism and transport of cholesterol and other fats in the body, particularly in the central nervous system.

The APOE protein is primarily involved in the transport and metabolism of lipids in the blood, where it helps to carry cholesterol and other lipids to and from cells, and in the brain, where it helps to transport lipids across the blood-brain barrier.

In the brain, APOE helps to regulate the clearance of beta-amyloid protein, which is a key component of the plaques that form in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease. APOE is also involved in many other processes in the body, such as inflammation, immune function, and repair of tissues after injury.

In people with Alzheimer’s disease, there is reduced blood glucose uptake and energy (ATP) creation in the brain. Glucose enters the brain through glucose transporters in the blood-brain barrier. Brain glucose is tightly regulated.[ref]

The different APOE genotypes (E2, E3, E4) result in different-sized APOE molecules. Additionally, the different APOE types are associated with the level of plasma APOE.

The APOE E2 allele is linked to higher plasma APOE levels, while the APOE E4 allele is linked to lower plasma APOE levels. One study explained that “Low plasma levels of apoE are associated with increased risk of future Alzheimer’s disease and all dementia in the general population…”[ref]

Genotype report: Finding your APOE type from 23andMe

To determine your APOE type from your 23 and Me data or another source, you will need to look at the following two rs IDs: rs429358 and rs7412.

NOTE: AncestryDNA data should not be used for determining APOE type. There is a known error in the APOE gene data for certain years of their raw data files.[ref]

Other data files that work with Genetic Lifehacks membership, such as 23andMe, selfdecode, sequencing.com, or MyHeritage should work fine, although rare errors are always possible.

| APOE Allele | rs429358

Members: |

rs7412

Members: |

Risk of Alzheimer’s |

| ε2/ε2 | T/T | T/T | lower risk |

| ε2/ε3 | T/T | C/T | lower risk |

| ε2/ε4 | C/T | C/T | just slightly higher risk than normal |

| ε3/ε3 | T/T | C/C | normal risk |

| ε3/ε4 | C/T | C/C | higher than normal risk |

| ε4/ε4 | C/C | C/C | highest risk[ref] |

Video explanation of how to read the chart

APOE types:

You inherit one APOE allele from your mother and one from your father. Thus, you will have two APOE allele types. There are six possible combinations (listed above): E2/E2, E2/E3, E3/E3, E3/E4, E4/E4.

The APOE E3 type is the normal and most common type. For people with two copies of APOE E3, they will have what is considered the typical risk allele for Alzheimer’s disease. For people with an APOE E4 or E2 allele, the increase or decrease in risk from other APOE types is relative to the E3 allele.

What does APOE E4 mean?

APOE E4 elevates the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease compared to the more common version of the gene, APOE3. The APOE4 allele also increases the risk of developing the disease at a slightly younger age.

APOE2, on the other hand, can be protective against Alzheimer’s disease.

In addition to Alzheimer’s disease, APOE4 has also been linked to other brain conditions, including Lewy body dementia and TDP-43 pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Additionally, APOE E4 carriers are at a slightly increased relative risk of stroke and cardiovascular disease.[ref][ref]

Other factors involved in Alzheimer’s:

Again, your APOE gene isn’t the only factor involved in getting Alzheimer’s Disease.

- A minority of people with the E4/E4 alleles don’t end up with Alzheimer’s, but since some do not end up with Alzheimer’s, APOE is not completely penetrant.

- Environmental and lifestyle factors play a big role in who gets Alzheimer’s. (Covered in the Lifehacks for Alzheimer’s Prevention section below)

- Other genes could add to or decrease your risk.

- Check out my article on genetic mutations that decrease the risk of Alzheimer’s.

- Variants in the KLOTHO gene can decrease the APOE E4 elevated risk.

- A new research study found fibronectin variants are protective against Alzheimer’s in APOE4 individuals.

Thus, your APOE type isn’t the complete picture, but research does show it to be the most significant common genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease.

APOE E4 benefits:

For almost every genetic variant with a negative, there is also a tradeoff or benefit. This holds true even for the APOE E4 allele.

Parasite protection:

Studies in the Amazon show that older adults with the APOE E4 allele along with high parasite burdens were cognitively better off than those with the E3 or E2 alleles. Viral hepatitis C, Giardia, and cryptosporidium were cleared more easily.[ref]

Protective against age-related macular degeneration:

The APOE E4 allele has been shown in several studies to protect against macular degeneration.[ref]

Visual working memory benefits at age 70:

“ε4-carriers also recalled locations more precisely, with a greater advantage at higher β-amyloid burden. These results provide evidence of superior visual working memory in ε4-carriers, showing that some benefits of this genotype are demonstrable in older age, even in the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease.”[ref]

Infectious disease protection:

The APOE E4 allele is linked to a decreased risk of chronic hepatitis C and a lower risk of liver problems in people who have hepatitis C. [ref]

Obesity Paradox for APOE and Dementia:

People who are obese have been shown in studies to be at a greater risk of dementia, but not all studies show this result. It turns out that the APOE allele may be the difference.

A recent study showed that people with APOE E2 and APOE E3 alleles are at a greater risk of cognitive decline or dementia if they are obese. However, obesity was protective against dementia and Alzheimer’s when combined with the APOE E4 allele.[ref]

Lifehacks: Alzheimer’s Prevention

If you are at an increased risk for Alzheimer’s, the key is to use this knowledge to do all that you can to decrease your risk.

Download my free eBook on Alzheimer’s prevention

Research on Alzheimer’s prevention:

Circadian rhythm and Melatonin:

Number one on my list for preventing Alzheimer’s is blocking blue light at night to boost melatonin and help with circadian rhythm.

There is a ton of research showing a strong connection between circadian rhythm disruption, melatonin production, insulin regulation, and healthy brain aging.[ref][ref][ref][ref]

Our natural circadian rhythm causes melatonin to rise in the evening and stay elevated until morning. Light in the shorter, blue wavelengths signals through receptors in our eyes to turn off melatonin production in the morning.

However, our modern environment with electric lights at night, especially TVs and phones, disrupts our natural circadian rhythm.

You can either block blue light with 100% blue-light-blocking glasses or simply avoid electronics and bright overhead light for a couple of hours before sleep. Blue-blocking glasses, worn in the evening for several hours before bed, increase natural melatonin production by about 50% in just two weeks.[ref]

Read more about Light at Night and Alzheimer’s Risk. (in-depth on all the research on circadian rhythm)

What about supplemental melatonin?

Clinical trials are also evaluating the use of melatonin supplements for Alzheimer’s.[ref] Additionally, melatonin has been shown to positively reduce any increase in cardiovascular disease risk associated with the APOE E4 allele.[ref]

Read more about Supplemental Melatonin research studies and dosage details.

Brain energy and neurodegenerative diseases:

Alzheimer’s has been dubbed as “type 3 diabetes” by some researchers due to the changes in the way glucose is used in the brain. In addition to the decreased energy in the brain cells, an increase in inflammation is seen in Alzheimer’s and dementia patients.

A study in mice investigated the changes in metabolism in brain cells linked to Alzheimer’s and cognitive decline in aging. In this study, the researchers showed that energy production is reduced in microglia and macrophages in response to increased prostaglandin E2, an inflammatory signal. Specifically, prostaglandin E2 caused glucose to be stored as glycogen rather than being used for cellular energy production.

Most importantly, the study showed that inhibiting the EP2 receptor for prostaglandin E2 in myeloid cells was sufficient to increase cellular energetics. Blocking that prostaglandin EP2 receptor reversed cognitive aging in mice.[ref]

Saffron Extract:

Related Articles and Topics:

Genetic Mutations that Protect Against Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease is a scary possibility that faces many of us today — whether for ourselves or aging parents and grandparents. Currently, 10% of people aged 65 or older have Alzheimer’s disease (AD). It is a disease for which prevention needs to start decades before the symptoms appear.

Alzheimer’s and Light at Night: Taking action to prevent this disease

With the advent of consumer genetic testing from 23andMe, AncestryDNA, etc., it is now easy to know if you are at a higher risk of getting Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). Those with APOE-ε3 are at normal risk for Alzheimer’s, and those who carry an APOE-ε4 allele (or two) are at an increased risk.

TREM2 and Alzheimer’s Disease Risk:

Another important gene to check for Alzheimer’s risk is TREM2. Uncommon variants in this gene affect your brain’s immune response.

Serotonin 2A receptor variants: psychedelics, brain aging, and Alzheimer’s disease

Learn how new research on brain aging and dementia connects the serotonin 2A receptor with psychedelics, brain aging, and Alzheimer’s.

References:

“Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics Fact Sheet.” National Institute on Aging, https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-disease-genetics-fact-sheet. Accessed 29 Apr. 2022.

APOE – SNPedia. https://www.snpedia.com/index.php/APOE. Accessed 29 Apr. 2022.

Bessone, Fernando. “Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs: What Is the Actual Risk of Liver Damage?” World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG, vol. 16, no. 45, Dec. 2010, pp. 5651–61. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i45.5651.

Downer, Brian, et al. “The Relationship between Midlife and Late Life Alcohol Consumption, APOE E4 and the Decline in Learning and Memory among Older Adults.” Alcohol and Alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire), vol. 49, no. 1, Feb. 2014, pp. 17–22. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agt144.

Farrer, L. A., et al. “Effects of Age, Sex, and Ethnicity on the Association between Apolipoprotein E Genotype and Alzheimer Disease. A Meta-Analysis. APOE and Alzheimer Disease Meta Analysis Consortium.” JAMA, vol. 278, no. 16, Oct. 1997, pp. 1349–56.

in ’t Veld, Bas A., et al. “Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs and the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 345, no. 21, Nov. 2001, pp. 1515–21. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa010178.

Jenwitheesuk, Anorut, et al. “Melatonin Regulates Aging and Neurodegeneration through Energy Metabolism, Epigenetics, Autophagy and Circadian Rhythm Pathways.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 15, no. 9, Sept. 2014, pp. 16848–84. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms150916848.

Kim, Mari, et al. “Short-Term Exposure to Dim Light at Night Disrupts Rhythmic Behaviors and Causes Neurodegeneration in Fly Models of Tauopathy and Alzheimer’s Disease.” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, vol. 495, no. 2, Jan. 2018, pp. 1722–29. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.12.021.

Metformin | Cognitive Vitality | Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation. http://www.alzdiscovery.org/cognitive-vitality/condition/lithium-drug-treatments. Accessed 29 Apr. 2022.

Nunes, Marielza Andrade, et al. “Microdose Lithium Treatment Stabilized Cognitive Impairment in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease.” Current Alzheimer Research, vol. 10, no. 1, Jan. 2013, pp. 104–07. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.2174/1567205011310010014.

Paterniti, Irene, et al. “Neuroprotection by Association of Palmitoylethanolamide with Luteolin in Experimental Alzheimer’s Disease Models: The Control of Neuroinflammation.” CNS & Neurological Disorders Drug Targets, vol. 13, no. 9, 2014, pp. 1530–41. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.2174/1871527313666140806124322.

Rovio, Suvi, et al. “Leisure-Time Physical Activity at Midlife and the Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease.” The Lancet Neurology, vol. 4, no. 11, Nov. 2005, pp. 705–11. www.thelancet.com, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70198-8.

Seshadri, Sudha, et al. “Plasma Homocysteine as a Risk Factor for Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 346, no. 7, Feb. 2002, pp. 476–83. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa011613.

Shechter, Ari, et al. “Blocking Nocturnal Blue Light for Insomnia: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Journal of Psychiatric Research, vol. 96, Jan. 2018, pp. 196–202. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.10.015.

Shi, Le, et al. “Sleep Disturbances Increase the Risk of Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Sleep Medicine Reviews, vol. 40, Aug. 2018, pp. 4–16. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2017.06.010.

Shukla, Mayuri, et al. “Mechanisms of Melatonin in Alleviating Alzheimer’s Disease.” Current Neuropharmacology, vol. 15, no. 7, 2017, pp. 1010–31. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X15666170313123454.

Wang, Jun, et al. “Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease: JAD, vol. 44, no. 2, 2015, pp. 385–96. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-141506.

Zisapel, Nava. “New Perspectives on the Role of Melatonin in Human Sleep, Circadian Rhythms and Their Regulation.” British Journal of Pharmacology, vol. 175, no. 16, Aug. 2018, pp. 3190–99. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.14116.