Key takeaways:

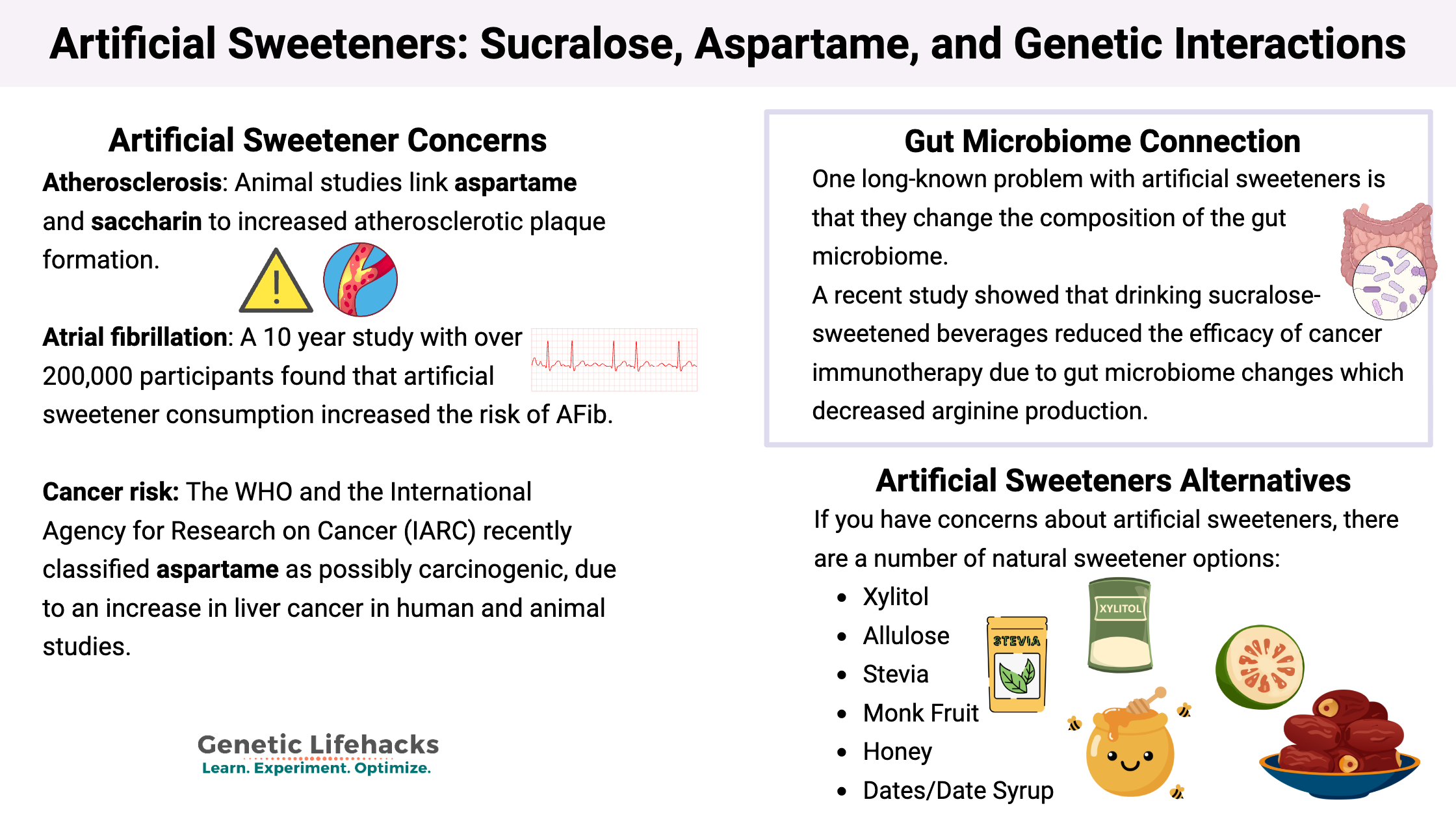

- Artificial sweeteners have been shown to increase atherosclerosis and the risk of AFib. They also change the gut microbiome and alter insulin sensitivity.

- Genetic susceptibility likely interacts with the risk seen in research studies.

- Understanding your genes can help you make decisions on whether risks outweigh the benefits for specific artificial sweeteners.

- Natural alternatives like allulose, monk fruit, and stevia are options that offer sweetness without glycemic impact.

Artificial sweeteners, genetic interactions, and long-term effects

Artificial sweeteners are a popular alternative to sugar-sweetened drinks and foods. Diet sodas hit the market in the 1980s, and their popularity has grown dramatically over the last two decades, with the determined push to reduce the consumption of sugar. Sugar consumption actually peaked in the late 90s.

Most of the initial toxicology studies on artificial sweeteners were done with animals, often using high doses, to see if there were gross observable negative effects, like death or tumors.[ref][ref]

Which artificial sweeteners are popular in different countries?

In the US, saccharin, aspartame, acesulfame potassium (Ace-K), sucralose, neotame, and advantame are FDA-approved, while in the EU, there are 19 different artificial sweeteners, with the most common being acesulfame K, aspartame, cyclamate, and sucralose. Stevia and monk fruit are given approval in the US as GRAS (generally recognized as safe).[ref]

Typical amounts consumed:

- Aspartame: One 12-oz diet soda ≈ 180-200 mg (diet Coke)

- Sucralose: One packet ≈ 12 mg (yellow packets)

- Saccharin: One packet ≈ 36 mg (pink packet)

- Ace-K: One diet soda ≈ 40 mg (Coke Zero, diet Pepsi)

The maximum recommended daily intake of aspartame is 40 mg/kg bodyweight in Europe and 50 mg/kg bodyweight in the United States.[ref]

Health Effects from Artificial Sweeteners

A number of studies have come out in the past couple of years that show serious negative long-term consequences from the various types of artificial sweeteners. Some studies lump the artificial sweeteners together, while others take a deeper dive into the individual types of sweeteners.

| Outcome / system | Sweetener(s) involved | Key finding (relative risk / effect size) | Study type / population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atherosclerosis | Aspartame | 0.05–0.15% aspartame increased insulin, driving endothelial inflammation and plaque formation in mice/monkeys. | Animal models (mice, monkeys) |

| Atherosclerosis + TMAO | Saccharin | 0.1 mg/mL saccharin for 3 months aggravated plaque and elevated circulating TMAO; gut barrier and endothelial dysfunction. | Animal atherosclerosis model |

| Atrial fibrillation | Mixed artificial sweeteners (beverages) | >2 L/week artificially sweetened drinks → ~20% higher AFib risk; sugar-sweetened drinks ~10% higher; real juice ~8% lower risk. | Prospective cohort, >200,000 adults |

| Atrial fibrillation (genetic) | Mixed artificial sweeteners | In high genetic-risk participants, artificially sweetened drinks associated with >250% higher AFib risk; in diabetes, 1/day → 21% higher risk. | Large cohort analyses (general and diabetic) |

| Stroke | Mixed artificial sweeteners | ≥2 artificially sweetened drinks/day → ~23% higher stroke risk in older women; similar findings in another large cohort. | Prospective cohorts (e.g., WHI) |

| Stroke pathways | Aspartame | 2025 analysis implicates upregulated inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF) as a mechanistic link to stroke. | Mechanistic/integrative analysis |

| Insulin sensitivity | Sucralose | ~30% ADI for 30 days caused ~20% decrease in insulin sensitivity with higher BCAA and inflammatory markers. | RCT in healthy, lean adults |

| Gut dysbiosis & insulin | Sucralose | 10 weeks of sucralose-sweetened beverages: ~3-fold ↑ Blautia coccoides, 0.66-fold ↓ L. acidophilus, ↑ serum insulin. | Human clinical trial |

| Gene expression / inflammation | Sucralose + Ace-K | Diet soda (sucralose + Ace-K) 3×/day for 8 weeks in non-users: 828 genes altered; upregulation of TNF and other inflammatory regulators. | Small human intervention study |

| Cancer (aspirational summary) | Aspartame | Classified “possibly carcinogenic”; recent work details a pathway linking aspartame to increased liver cancer risk. | IARC assessment + mechanistic studies |

| Cancer (multiple sites) | Grouped artificial sweeteners | Integrated analyses link higher intake to increased relative risk of kidney, low-grade glioma, breast, and prostate cancers. | Network toxicology + observational data |

| Neurotoxicity | Aspartame + metabolites | 271.7 µM aspartame or metabolites caused oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage, and reduced cardiolipin in neuronal cells. | In vitro neuronal cell study |

| Immunotherapy response | Sucralose | Sucralose-sweetened beverages reduced cancer immunotherapy efficacy via gut microbiome changes and loss of arginine-producing microbes. | Human and/or translational oncology study |

Let’s dive into the details on all of these studies and look at possible genetic connections:

Atherosclerosis:

Atherosclerosis is caused by inflammation and the buildup of plaque in the arteries.

- Atherosclerosis and aspartame: A new 2025 study published in Cell Metabolism showed that aspartame consumption (0.05 – 0.15%) markedly increased insulin secretion in mice and monkeys. This insulin elevation increased atherosclerotic plaque formation through an insulin-dependent mechanism that triggers inflammation in the lining of the arteries.[ref]

- Saccharin and atherosclerosis: Another 2025 study found that saccharin supplementation (0.1 mg/mL in drinking water for 3 months) significantly aggravated atherosclerotic plaque formation in an animal model of atherosclerosis. The researchers also found that saccharin elevated circulating TMAO (trimethylamine oxide) levels, caused gut mucosal barrier dysfunction, and endothelial dysfunction.[ref]

Atrial fibrillation:

A 2024 study using over 200,000 participants followed for 9 years showed that drinking artificially sweetened beverages (>2L/week) increased the relative risk of atrial fibrillation by 20%. In comparison, drinking >2L/week of sugar-sweetened beverages increased the risk of AFib by 10%. Drinking real juice decreased AFib risk by 8%. Importantly, the people who were at a genetically increased risk of atrial fibrillation who drank artificially sweetened beverages were at a more than 250% increased relative risk of AFib.[ref] In people with diabetes, drinking just one artificially sweetened beverage a day increased the risk of AFib by 21%.[ref]

Here are some of the genetic risk factors for AFib. If you have variants here, please read the full article on atrial fibrillation.

| Gene | RS ID | Your Genotype | Effect Allele | Effect Allele Frequency | Notes About Effect Allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PITX2 | rs2200733 | -- | T | 0.14 | increased relative risk of atrial fibrillation |

| PITX2 | rs10033464 | -- | T | 0.1 | increased relative risk of atrial fibrillation |

| PITX2 | rs13143308 | -- | T | 0.24 | increased relative risk of atrial fibrillation |

| PITX2 | rs3853445 | -- | C | 0.26 | decreased relative risk of atrial fibrillation |

| ZFHX3 | rs2106261 | -- | T | 0.17 | increased relative risk of atrial fibrillation |

| CAV1 | rs11773845 | -- | C | 0.42 | increased relative risk of atrial fibrillation |

| CAV1 | rs3807989 | -- | A | 0.4 | decreased relative risk of atrial fibrillation |

| SCN5A | rs6599230 | -- | T | 0.2 | decreased relative risk of atrial fibrillation due to non-pulmonary vein triggers |

| SCN5A | rs6843082 | -- | G | 0.25 | decreased relative risk of atrial fibrillation due to non-pulmonary vein triggers |

| SCN10A | rs6801957 | -- | T | 0.39 | lower SCN5 expression, slowed conduction, slightly decreased risk of AF |

| KCNN3 | rs13376333 | -- | T | 0.28 | increased risk of lone AFib |

| HCN4 | rs7164883 | -- | G | 0.16 | increased relative risk of atrial fibrillation |

| PRRX1 | rs3903239 | -- | G | 0.42 | increased relative risk of atrial fibrillation |

Gene expression changes, TNF upregulation:

A small study in adults who normally didn’t consume artificial sweeteners looked at the effect of drinking a 12-oz can of diet soda containing sucralose and acesulfame-potassium (Ace-K) three times a day for 8 weeks. The researchers looked at gene expression and found that 828 genes were differentially expressed. Of note, several key regulators of inflammation, including increased TNF-alpha, were found.[ref]

Some people naturally have increased TNF levels due to genetic variants. If you have variants highlighted below (especially the first SNP), please read the full article on TNF.

| Gene | RS ID | Your Genotype | Effect Allele | Effect Allele Frequency | Notes About Effect Allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF | rs1800629 | -- | A | 0.15 | Increased TNF alpha, increased risk of many chronic inflammatory diseases |

| TNF | rs361525 | -- | A | 0.05 | Increased TNF alpha, increased risk of many chronic inflammatory diseases |

| TNF | rs1799964 | -- | C | 0.21 | Increased TNF alpha, increased risk of many chronic inflammatory diseases |

| TNF | rs1799724 | -- | T | 0.12 | Increased TNF alpha, increased risk of many chronic inflammatory diseases |

| TNFRSF1A | rs1800693 | -- | C | 0.39 | Increased risk of multiple sclerosis; increased NF-kB signaling |

| TNFRSF1A | rs767455 | -- | C | 0.42 | Increased risk of inflammatory diseases. |

| TNFRSF1B | rs1061622 | -- | G | 0.23 | Increased risk of psoriasis, lupus |

| TNF | rs1800610 | -- | A | 0.08 | Lower TNF; less inflammation but more susceptible to infectious diseases |

Stroke risk:

A study involving more than 80,000 older women found that participants consuming two or more artificially sweetened beverages a day had a 23% increased relative risk of stroke. Another large study found a similar result with increased risk of stroke in adults drinking more than one artificially sweetened beverage per day.[ref][ref] A 2025 analysis looked at pathways that were upregulated by aspartame as a possible reason for stroke. The study found that several inflammatory cytokines were likely involved, including IL-1β and TNF.[ref]

Changes in insulin sensitivity, sucralose:

A recent study in healthy, lean adults found that sucralose consumption for 30 days caused a 20% decrease in insulin sensitivity. This was accompanied by (or caused by?) changes in the gut microbiome as well as an increase in BCAA levels. [ref]

The link to increased BCAAs is also found in genetic studies on the cause of insulin resistance. See your genotypes below and read the full article on insulin resistance here.

| Gene | RS ID | Your Genotype | Effect Allele | Effect Allele Frequency | Notes About Effect Allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPM1K | rs1440581 | -- | C | 0.54 | C/C: On average, higher BCAA levels compared to TT. For people on a reduced-calorie diet, a low-fat diet worked better for reducing insulin resistance. |

| PPM1K | rs9637599 | -- | C | 0.5 | On average, higher BCAA levels; Increased risk of insulin resistance and diabetes with high BCAA intake |

| BCAT1 | rs2242400 | -- | G | 0.11 | increased BCAAs, increased risk of diabetes |

| GPRC6A | rs2274911 | -- | G | 0.26 | G/G: decreased risk of insulin resistance (amino acid receptor) |

| IRS1 | rs1801278 | -- | T | 0.06 | impaired IRS1 signaling, increased risk of insulin resistance and diabetes (insulin receptor) |

| ENPP1 | rs1044498 | -- | C | 0.17 | increased risk of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome (helped by exercise)) |

| PCK1 | rs2179706 | -- | C | 0.54 | C/C: When consuming higher omega-3 PUFA, individuals had lower insulin resistance levels on average |

| IGF1 | rs35767 | -- | G | 0.8 | lower insulin sensitivity, increased risk of insulin resistance |

| NAT2 | rs1208 | -- | G | 0.42 | decreased risk of insulin resistance |

| IRS1 | rs2943641 | -- | C | 0.65 | C/C: increased risk of insulin resistance; C/T: typical risk; T/T: lower risk of type 2 diabetes in people with high vitamin D levels[ |

Artificial sweeteners and cancer risk:

- Aspartame: The WHO and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) recently classified aspartame as possibly carcinogenic. This was primarily based on the increased risk of liver cancer seen in human and animal studies.[ref] A 2025 study elucidated the pathway by which aspartame increases the risk of liver cancer.[ref]

- Integrated data study: A thorough study that used network toxicology, molecular dynamics, machine learning, and integrated data mining along with clinical samples, found that artificial sweeteners (grouped data) increase the relative risk of kidney cancer, low-grade glioma, breast cancer, and prostate cancer.[ref] While the study was extensive and looked at how and why artificial sweeteners statistically increase the risk of certain cancers, it is important to keep the risk in perspective. There are a lot of things that increase cancer risk a little bit, just as there are many lifestyle factors that can decrease cancer risk a little bit. The negative effects of artificial sweeteners on the arteries, brain, and gut microbiome are likely more impactful than the cancer risk.

Gut Microbiome and TMAO Connection

One long-known problem with artificial sweeteners is that they change the composition of the gut microbiome.[ref][ref] To some extent, a lot of sugar will also change the gut microbiome, so it is a complex topic to sort out.

- Shift in composition: In a gut microbiome study, participants drank sucralose-sweetened beverages for 10 weeks. The results showed a 3-fold increase in Blautia coccoides and a 0.66-fold decrease in Lactobacillus acidophilus. The participants also had increased serum insulin compared to water.[ref]

- The TMAO Pathway: TMAO – trimethylamine oxide – is thought to have a causal adverse effect on atherosclerosis. Several studies have identified that artificial sweeteners can affect atherosclerosis through gut microbiome alterations and TMAO production. In animal studies, saccharin consumption causes a marked elevation in circulating TMAO levels and atherosclerosis.[ref]

Related article: FMO3, TMAO

Sucralose, immunotherapy, and gut microbiome changes:

A recent study showed that drinking sucralose-sweetened beverages reduced the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy by quite a lot. The researchers found that the changes to the gut microbiome were such that the microbes that produce arginine were depleted. Under normal circumstances, this wasn’t a problem because arginine can be synthesized in the body in other ways. However, T cells rely on arginine, and in immunotherapy for cancer, the T cell exhaustion occurred more quickly in people drinking sucrolose due to the altered gut microbiome not producing arginine.[ref]

If you’re undergoing immunotherapy or have long Covid or a chronic viral infection, you can check your T cell exhaustion genes and read more here.

| Gene | RS ID | Your Genotype | Effect Allele | Effect Allele Frequency | Notes About Effect Allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIM3 | rs13170556 | -- | C | 0.14 | increased susceptibility to T cell exhaustion, which increases risk of chronic lung infections |

| PDCD1 | rs2227981 | -- | A | 0.42 | Lower PDCD1 expression, theoretically less likely to have T cell exhaustion; reduced cancer risk |

| PDCD1 | rs10204525 | -- | T | 0.15 | Likely higher PDCD1 expression, more likely to have T cell exhaustion; increased cancer risk |

| CTLA4 | rs231775 | -- | G | 0.38 | decreased risk of T cell exhaustion in cancer therapy (greater survival rates); increased risk of autoimmune disease |

| LAG3 | rs3782735 | -- | G | 0.39 | increased survival in gastric cancer (likely lower LAG3, less T cell exhaustion) |

| LRRC8C | rs10493829 | -- | C | 0.41 | elevated LRRC8C, improved survival in certain cancers |

| HLA-DRB1 | rs660895 | -- | G | 0.21 | lower risk of T cell exhaustion; higher risk of rheumatoid arthritis (~6-fold) and autoimmune diseases (tag for HLA-DRB1*0401) |

| PDCD1 | rs2227982 | -- | A | 0.03 | higher PDCD1 expression; more likely to be a non-responder to chemotherapy for cervical cancer |

| CTLA4 | rs3087243 | -- | A | 0.43 | higher CTLA4 levels; more likely to be a non-responder to chemotherapy for cervical cancer |

Neurotoxicity of aspartame:

A 2023 study demonstrated that aspartame and its metabolites cause oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage in neuronal cells. The study found that treatment with aspartame (271.7 µM) or its metabolites resulted in elevated oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage, and reduced cardiolipin levels. This raises concerns about neurotoxicity even at recommended doses.[ref]

Metabolism and Excretion of Artificial Sweeteners

Each artificial sweetener is absorbed, metabolized, and excreted in different ways.

Aspartame:

Aspartame is rapidly and completely hydrolyzed in the small intestine into three metabolites:[ref]

- Phenylalanine (50% by weight) – an essential amino acid

- Aspartic acid (40% by weight) – a non-essential amino acid

- Methanol (10% by weight) – a simple alcohol

These three metabolites are then absorbed into the bloodstream and used or excreted in specific ways:

- Aspartic acid: Enters the citric acid cycle and amino acid pools

- Methanol: Metabolized by alcohol dehydrogenase to formaldehyde, then to formic acid

- Phenylalanine: Normally converted to tyrosine, but can be a problem for someone with a phenylketonuria mutation

Check to see if you carry a rare mutation related to phenylketonuria below. If anything is highlighted, read the full article here.

| Gene | RS ID | Your Genotype | Effect Allele | Effect Allele Frequency | Notes About Effect Allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAH | rs5030861 | -- | T | 0.001 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | rs5030858 | -- | A | 0.001 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | rs5030857 | -- | A | 0.0009 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | rs5030855 | -- | T | 0.0003 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | rs5030853 | -- | A | 0.0007 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | rs5030852 | -- | A | 0 | Phenylketonuria *mutation may be either A or T |

| PAH | rs5030849 | -- | T | 0.0002 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | rs5030841 | -- | G | 0.0001 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | rs28934899 | -- | G | 0 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | rs62508588 | -- | T | 0.00006 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | i4000479 | -- | C | 0 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | i4000478 | -- | T | 0 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | rs62514953 | -- | A | 0 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | rs62516092 | -- | C | 0.0002 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | rs62642933 | -- | C | 0.0001 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | rs62642932 | -- | T | 0 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | rs76296470 | -- | A | 0.0005 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | rs75193786 | -- | G | 0.0005 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | i4000470 | -- | C | 0 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | i4000467 | -- | A | 0 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | rs5030860 | -- | C | 0.0004 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | rs5030856 | -- | C | 0.0002 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | i3003401 | -- | A | 0 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | i4000472 | -- | G | 0 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | i4000473 | -- | A | 0 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | i3003397 | -- | T | 0 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | i4000481 | -- | T | 0 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | i3003398 | -- | A | 0 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | i3003399 | -- | A | 0 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | i3003400 | -- | A | 0 | Phenylketonuria |

| PAH | i4000476 | -- | C | 0 | Phenylketonuria |

Sucralose:

Sucralose is a chlorinated derivative of sucrose (1,6-dichloro-1,6-dideoxy-β-D-fructofuranosyl-4-chloro-4-deoxy-α-D-galactopyranoside).

Sucralose is essentially biologically inert – it passes through the body largely unchanged because human digestive enzymes cannot break the modified sugar bonds. Only 15% is absorbed, with the rest being excreted in the feces. Of the absorbed portion, most of that is excreted in the urine. A minor portion is metabolized using glucuronidation and hydrolysis.[ref]

Interesting point: Sucralose is structurally similar to chlorinated compounds such as perfluoralkyl substances (PFAS). Similar to PFAS, sucralose persists in the environment and isn’t broken down. This could be an environmental problem for aquatic organisms, and the presence of sucralose shifts the environmental microbiota composition. [ref]

Saccharine:

Saccharine is almost completely absorbed into the bloodstream and then is excreted in the urine within 24-48 hours.[ref]

Acesulfame Potassium (Ace-K):

Similarly, Acesulfame Potassium (Ace-K) is rapidly and completely absorbed from the intestines and then is excreted unchanged in the urine in about 24 hours.

Lifehacks: Alternatives to Artificial Sweeteners

If you have concerns about artificial sweeteners, there are a number of natural sweetener options:

Xylitol:

A sugar alcohol derived from birch bark, xylitol is equal in sweetness to table sugar with about 40% fewer calories. It also has a lower glycemic index than sugar. One drawback is that it can cause gastrointestinal stress to some people. It is also toxic to pets.[ref]

Allulose:

Allulose is a rare type of sugar found in wheat, figs, and raisins. It is about 70% as sweet as sugar, with only about 10% of the calories. It also has a very low glycemic index (doesn’t raise blood sugar). It’s not a sugar alcohol, and thus usually doesn’t cause gastrointestinal side effects.[ref]

Stevia:

Derived from the leaves of the Stevia rebaudiana plant, stevia is about 200X sweeter than sugar with zero calories. It does not raise blood glucose levels. Some people, though, can taste the bitter aftertaste for stevia. (Check your stevia taste receptor variants here.)

Monk Fruit (Luo Han Guo):

Monk fruit sweeteners are 150-200X sweeter than sugar with zero calories and no blood glucose elevation. One thing to note is that it is often combined with erythritol, which is a sugar alcohol that may cause gastrointestinal problems for some people.

Honey:

Honey is actually about 1.5X sweeter than sugar, so you can use less of it. It also has less of an impact on blood sugar levels due to the high fructose content. However, it may not be a good option in high quantities for someone who is concerned about the liver effects of fructose.

Maple Syrup:

Similar to sugar in sweetness, it has a lower glycemic index than sugar.

Coconut sugar:

Tastes more like brown sugar in flavor, but with a lower glycemic index than sugar.

Related articles and topics:

T Cell Exhaustion in Long COVID, ME/CFS, and Cancer: Mechanisms and Solutions

Coronary Artery Disease: Genetic Susceptibility to Heart Disease

References: