Key takeaways:

~ The CYP2C8 gene encodes an enzyme that metabolizes several common medications.

~ Variants in CYP2C8 can impact your risk for GI bleeding from NSAIDs.

~ Understanding your genetic variants can help you understand your reaction to medications.

CYP2C8: From omega-6 fatty acids to ibuprofen

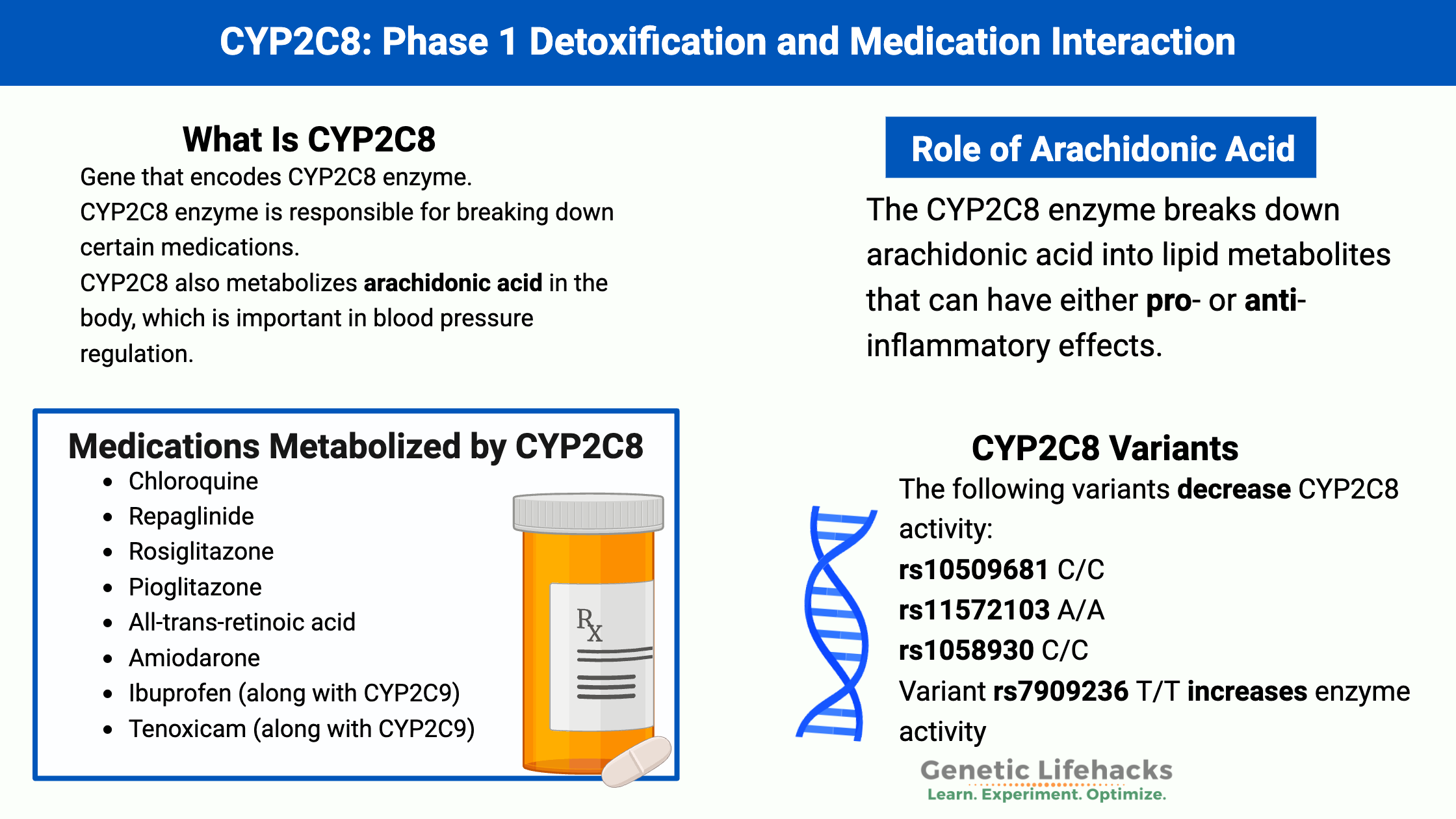

The CYP (cytochrome) family of genes codes for multiple enzymes that interact with prescription medications, hormones, toxins, and fatty acids. This family of enzymes is important in breaking down medications in a process known as phase I detoxification. Genetic variants that alter how these enzymes work are responsible for varied individual responses to medications.

Let’s take a look first at the role CYP2C8 plays in breaking down polyunsaturated fats and then go into the medications and toxicants impacted by the gene.

CYP2C8 and PUFAs:

The CYP2C8 enzyme breaks down arachidonic acid into lipid metabolites that can have either pro- or anti-inflammatory effects.[ref] Arachidonic acid is an omega-6 fatty acid that we can get from certain foods or convert from linoleic acid (from soybean oil, corn oil, safflower oil, etc). Arachidonic acid and other polyunsaturated fatty acids can be converted in cells into bioactive molecules that signal for inflammation or for the resolution of inflammation.[ref]

CYP2C8, CYP2C9, and CYP2J2 are all involved in forming epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) from arachidonic acid. The EETs can be anti-inflammatory and help blood vessels to relax. However, they are short-lived and are broken down into pro-inflammatory molecules when overproduced.[ref] CYP2C8 can also form hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs) primarily in the lungs.[ref]

The metabolism of arachidonic acid by CYP2C8 is also important in eye health in aging. Hypoxia, or low oxygen, increases CYP2C8, which in turn causes more of the conversion of arachidonic acid into epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs). The increased EETs then promote abnormal vascular development in the retina of the eye.

Additionally, the increased CYP2C8 interacted with omega-3 fatty acids, promoting abnormal vascular development with higher levels of DHA in low oxygen conditions.[ref]

Inhibiting CYP2C8 has been shown in studies to decrease the pathological effects in the eye from increased vascular development. This could be important in age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy.[ref] Please keep in mind that you don’t want to inhibit CYP2C8 if you are on a prescription medication that relies on the enzyme.

Medications metabolized by CYP2C8:

The CYP2C8 gene is essential in the metabolism of several chemotherapy drugs and plays a role in the metabolism of NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen.

Medications that are mainly metabolized by CYP2C8 include[ref]:

- Chloroquine

- Repaglinide

- Rosiglitazone

- Pioglitazone

- All-trans-retinoic acid

- Amiodarone

- Ibuprofen (along with CYP2C9)

- Tenoxicam (along with CYP2C9)

For people with genetic variants in CYP2C8 that decrease the function of the enzyme, a medication may remain in their system longer and could build up to a toxic amount. Your doctor or pharmacist should be able to help in dialing in the right dosage.

Keep in mind that some medications can be metabolized using more than one CYP enzyme, so a decrease in CYP2C8 function may interact with other CYP variants in determining your reaction to medications.

The ClinPGx database is a good source of information on pharmacological and genetic interactions. It has information on the CYP2C8 variants and response to tacrolimus, montelukast, rosiglitazone, and pioglitazone.

Natural supplements that interact with CYP2C8:

Natural supplements that you take can also interact with the CYP450 enzymes.

- quercetin (inhibitor of CYP2C8)[ref]

- pterostilbene and trans-resveratrol (inhibitor)[ref]

- luteolin (inhibitor)[ref]

- diosmetin (inhibitor)[ref]

CYP2C8 Genotype Report:

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks: What to avoid with CYP2C8 variants

If you have the CYP2C8*3 variant and regularly take NSAIDs, you should talk with your doctor about the increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Check to see if you also have CYP2C9 variants:

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

Nrf2 Pathway: Increasing the Body’s Ability to Get Rid of Toxins

References: