Key takeaways:

~ The GST family of genes encodes eight different enzymes that combine with glutathione in the elimination of many different environmental toxins.

~ Genetic variants in the GST genes impact your ability to detoxify specific toxins.

~ Understanding where your genetic susceptibility lies may help you to know which toxicants to avoid.

This article explains how glutathione is utilized to detoxify certain toxicants. I’ll explain the glutathione-S-transferase genes and the impact that genetic variants have on phase II detoxification.

Members will see their genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Join today.

GSTs: phase II detoxification enzymes

Exposure to many different man-made chemical compounds occurs every day, and our exposure to new toxicants well exceeds what our ancestors experienced.

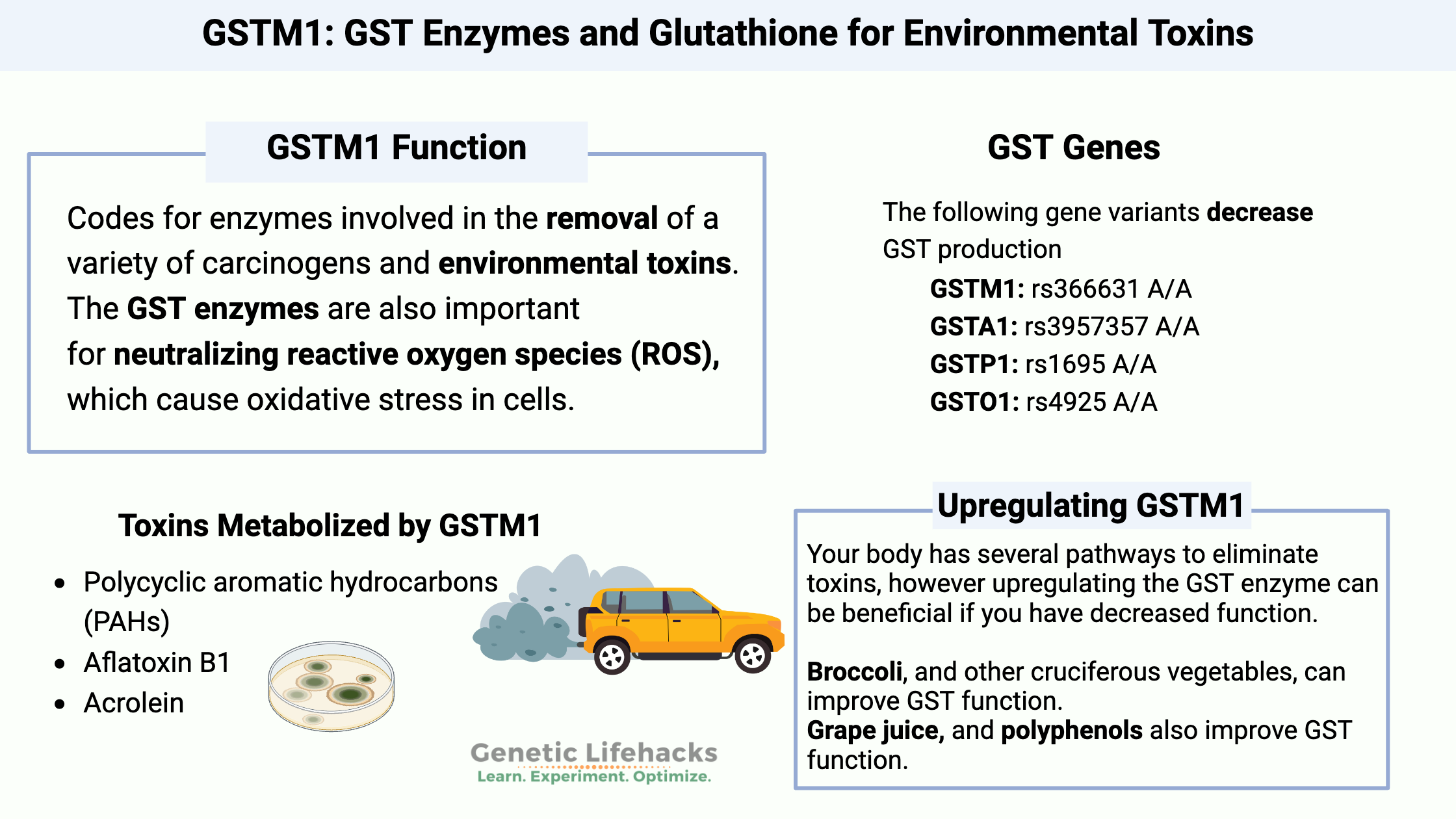

The glutathione S-transferase genes code for enzymes involved in the removal of a variety of carcinogens and environmental toxins.[ref]

These phase II detoxification enzymes combine the metabolites from phase I with molecules that make them less toxic and more easily excreted.

There are eight different enzymes in the GST family of genes identified by Greek letters: alpha, kappa, mu, omega, pi, sigma, theta, and zeta. As such, abbreviations for the classes start with their first letter (i.e., GSTMA for alpha).

The GST enzymes are found in the liver, intestines, and several other tissues. They are responsible for detoxifying a large number of pesticides, herbicides, carcinogens, and chemotherapy drugs.

Glutathione, an endogenous antioxidant

The GST enzymes conjugate (bind) an antioxidant called glutathione to the substance for elimination. Glutathione is considered the master antioxidant for the body.

Related article: Glutathione synthesis and genetic variants

Once a toxic substance has been conjugated with glutathione via the GST-specific enzyme, the body excretes it via bile or urine.

Toxins neutralized by GSTs

The GST enzymes and glutathione conjugation is important in detoxifying hundreds of different environmental toxicants. Here are just a few examples:

- The GST enzymes are essential in detoxifying polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are carcinogenic. Cigarette smoke, diesel exhaust, and grilled meats all contain PAHs.[ref]

- Aflatoxin B1, a fungal component found on grains and peanuts, is detoxified by conjugation with glutathione using GST enzymes.[ref]

- Acrolein is an aldehyde used as a pesticide and a byproduct of tobacco smoke. It also forms when frying foods in oil at high temperatures.[ref]

Reducing oxidative stress:

In addition to their role in removing toxicants, the GST enzymes are also important for neutralizing reactive oxygen species (ROS) which cause oxidative stress in cells.[ref][ref]

Genetic variants that decrease GST enzyme function increase the susceptibility to diseases that are caused by oxidative stress, such as neurodegenerative diseases, cancers, epilepsy, and ataxia.[ref]

What happens when you have reduced GST function?

Several fairly common genetic variants can decrease the function of the GST enzymes, but with several different GST enzymes available, your body usually has a backup route for getting rid of toxicants.

Importantly, environmental factors, such as exposure to toxicants (pollution, cigarette smoke), also play a large role here. It really is a matter of genetic susceptibility along with exposure to toxins and carcinogens.

I’ll cover ways to increase GST function in the Lifehacks section.

GST Genotype Report:

Genetic variants greatly impact the way that your GST genes function, with common variants causing non-functioning genes.

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks: Optimizing diet, supplements, and environment with GST SNPs

There are several dietary ways to naturally increase the amount of GST enzymes the body produces.

Lifestyle factors with GST variants:

Stop smoking and avoid second-hand smoke:

Studies have linked the GSTM1 null genotype with a 46% increase in the risk of lung cancer in smokers.[ref]

Avoid Radon:

People with GSTM1 null genotypes are at a 3-fold increased risk of lung cancer with radon exposure.[ref]

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

BPA and BPS: How Your Genes Influence Bisphenol Detoxification

References: