Key takeaways:

- ApoB is a protein found in LDL, VLDL, Lp(a), and chylomicrons, with one ApoB per particle.

- ApoB is a better predictor of heart disease risk than LDL-C or total cholesterol.

- Genetic variants can increase or decrease ApoB levels. Understanding your genetic variants can help you to prioritize diet and lifestyle factors, which also play a strong role in ApoB levels.

Members will see their genotype report below and the solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.What is ApoB?

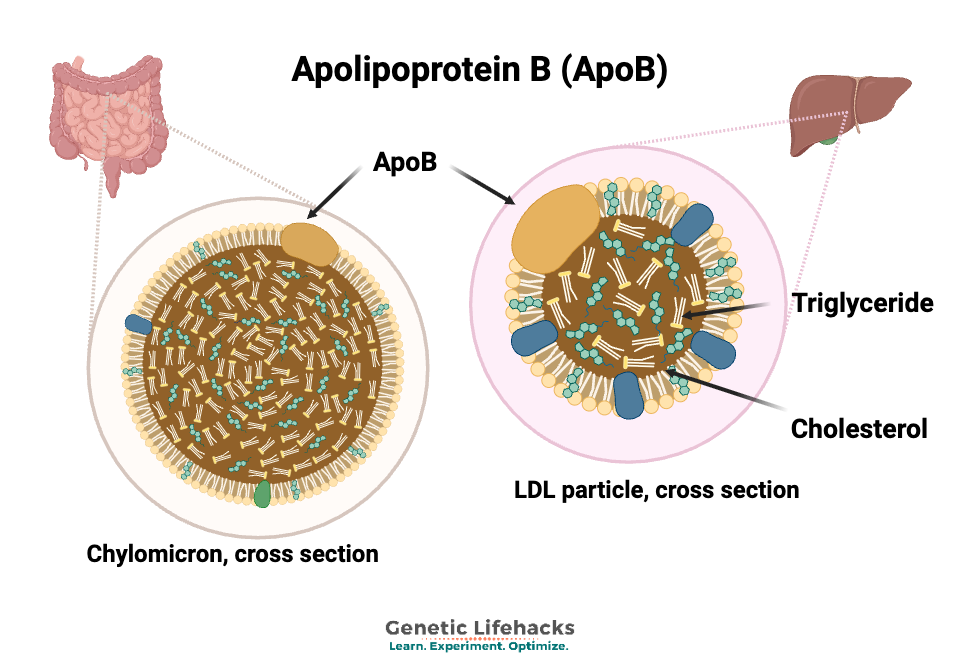

Lipids, such as cholesterol, are packaged up into lipoproteins in order to be transported through the body and delivered to their target tissues.

ApoB (Apolipoprotein B) is a component of:

- LDL (low-density lipoprotein)

- VLDL (very-low-density lipoproten)

- Lipoprotein (a) – Lp(a)

- Chylomicrons

There is one ApoB particle per lipoprotein, meaning there is one in each LDL particle and in each Lp(a). This makes it a direct marker of the number of lipoprotein particles in circulation.[ref][ref]

ApoB enables the various-sized LDL particles to bind to LDL receptors on cells, which then facilitates the clearance of cholesterol from the bloodstream.

Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) in chylomicron and LDL particles. Why is ApoB important?

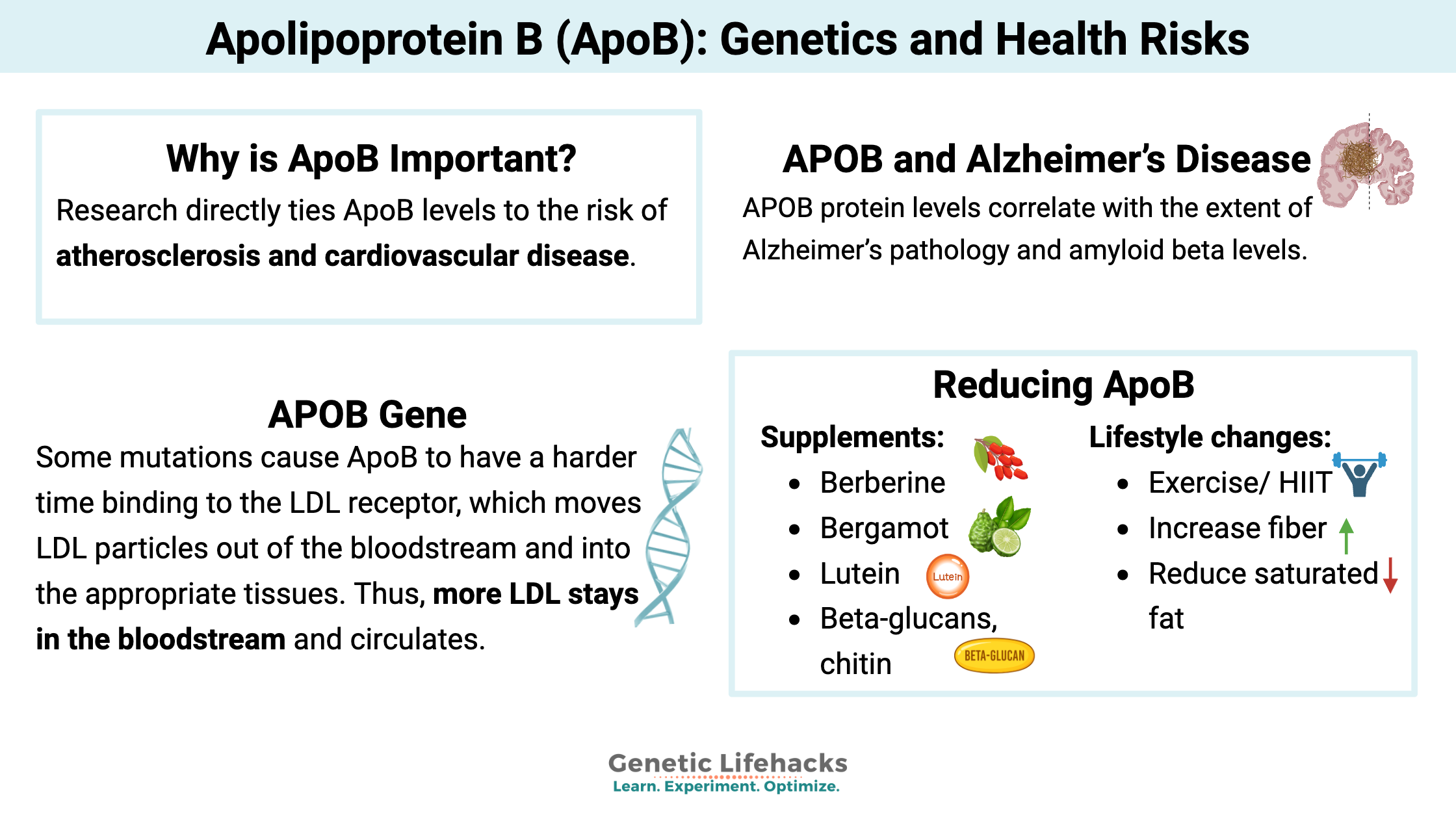

Newer research directly ties ApoB numbers to the risk of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. Research shows that it is a better marker than LDL, VLDL, triglycerides, or total cholesterol for understanding your risk of heart disease.[ref]

The mass of cholesterol within ApoB particles is variable, but in the walls of the artery, the number of ApoB particles is thought to equally contribute to atherosclerosis. Thus, many cardiologists now look at ApoB levels as a simple and unified measure of cardiovascular risk.[ref]

While LDL-C and ApoB levels are often concordant for people, sometimes the levels don’t line up — some people have higher ApoB without elevated LDL. In these cases, the high ApoB is a better predictor of the risk of heart disease. Thus, many cardiologists are moving toward measuring ApoB to better understand risk.

What is a normal ApoB level?

While a normal ApoB level is generally considered >100 mg/dL, the expert consensus of the National Lipid Association sets target ApoB levels to be lower than that if you have other risk factors for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. The target for borderline to intermediate risk is ApoB of 90 mg/dL or less, while those at a higher risk (high cholesterol or type 2 diabetes) have a target ApoB of below 70 mg/dL.[ref]

ASCVD Risk Level Target ApoB (mg/dL) Low/General <100 Borderline/Intermediate ≤90 High risk (CVD, T2D) <70 A meta-analysis of 25 drug trials found that “each 10-mg/dl decrease in apoB was associated with a 9% decrease in coronary heart disease”.[ref]

Does everyone with high ApoB have plaque in their arteries? Well, no. However, in someone who initially has some plaque, an elevation in ApoB, such as seen in some people on a ketogenic diet (LMHRs), can increase plaque scores.[ref] This is where a doctor can help with getting the appropriate tests done, such as a coronary artery calcium score, to determine your individual risk.

APOB gene and forms of ApoB:

A single APOB gene encodes two forms of ApoB – a longer one called ApoB-100 and a shorter version called ApoB-48.[ref] ApoB-100 is synthesized in the liver and incorporated into each lipoprotein particle. ApoB-100 acts as a ligand to bind to the LDL receptor. ApoB-48 is synthesized in the intestines and incorporated into chylomicrons, which transport triglycerides and cholesterol from food to the rest of your body (muscle, liver, adipose tissue, etc).

Form Synthesis Site Lipoprotein Association Function ApoB-100 Liver LDL, VLDL, Lp(a) Binds LDL receptor, clears cholesterol from the bloodstream ApoB-48 Intestine Chylomicrons Transports dietary fat, triglycerides, and cholesterol from the gut Genetic variants in APOB alter your levels:

Mutations and polymorphisms in the APOB gene can affect its function in multiple ways. The common polymorphisms alter ApoB and LDL levels a little bit, while rare mutations have a large effect size, either increasing or decreasing ApoB and LDL levels significantly.[ref]

Studies in twins show that genetics accounts for 50-60% of ApoB levels, while diet and lifestyle account for the rest.[ref]

High cholesterol (hypercholesterolemia) APOB mutations

Some mutations cause ApoB to have a harder time binding to the LDL receptor, which moves LDL particles out of the bloodstream and into the appropriate tissues. Thus, more LDL stays in the bloodstream and circulates. This causes a type of familial hypercholesterolemia, or high cholesterol, that can result in atherosclerosis and xanthomas.[ref]

Low cholesterol (hypobetalipoproteinemia) mutations:

Other mutations cause low levels of ApoB to be produced. This causes familial hypobetalipoproteinemia. The defective synthesis and export of ApoB then causes very low LDL cholesterol test levels, but it can also lead to the accumulation of triglycerides in the liver. People with hypobetalipoproteinemia are at a significantly higher risk of developing fatty liver disease. [ref]

Individuals who carry one copy of an APOB hypobetalipoproteinemia mutation often show levels of ApoB to be about a third to half of normal. Even with just one copy of an APOB mutation and low ApoB, there is still an increased risk of developing fatty liver disease.[ref]

APOB and CYP27A1: Reverse Cholesterol Transport

Early genetic studies on ApoB levels identified that CYP27A1 polymorphisms affected ApoB. CYP27A1 encodes sterol 27-hydroxylase, an enzyme that converts cholesterol to 27-hydroxycholesterol, which is used primarily for the synthesis of bile acids.

APOB and Alzheimer’s Disease:

While ApoE has long been known to play a role in Alzheimer’s disease, recently, several studies have linked lifelong higher levels of ApoB to an increased relative risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Animal models show that excess ApoB throughout life increases amyloid beta levels in the brain.[ref]

In the brains of people who died at different stages of Alzheimer’s, APOB protein levels correlate with the extent of Alzheimer’s pathology and amyloid beta levels. Interestingly, the mRNA levels of APOB didn’t correlate, and the researchers think there is a link between blood-brain barrier dysfunction and the excess of APOB protein. Essentially, circulating levels of ApoB add to the problems in Alzheimer’s at later stages of the disease.[ref]

A Mendelian randomization study was used to determine whether ApoB levels are likely to play a causal role. A multivariable Mendelian randomization showed that high ApoB, rather than LDL, is likely to play a causal role in decreasing healthspan and possibly increasing Alzheimer’s risk.[ref]

ApoB interacts with diabetes and heart disease:

Insulin is released by the pancreas to promote the uptake of glucose into cells. Diabetes involves insulin resistance – cells are less responsive to insulin’s signals, so more insulin is released.

Insulin normally promotes the degradation of ApoB in the liver and decreases ApoB secretion. In insulin resistance, the insulin signaling is impaired, resulting in a decreased clearance of ApoB.[ref]

In people with diabetes, ApoB levels are significantly higher on average. This may be why cardiovascular disease is more often a problem in people with diabetes.[ref]

Genotype Report: APOB

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics

Statins and Brain Fog: Exploring how statins impact memory and cognitive function

References

Aceves-Ramírez, Maricela, et al. “Analysis of the APOB Gene and Apolipoprotein B Serum Levels in a Mexican Population with Acute Coronary Syndrome: Association with the Single Nucleotide Variants Rs1469513, Rs673548, Rs676210, and Rs1042034.” Genetics Research, vol. 2022, Mar. 2022, p. 4901090. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4901090.

Au, Anthony, et al. “The Impact of APOA5, APOB, APOC3 and ABCA1 Gene Polymorphisms on Ischemic Stroke: Evidence from a Meta-Analysis.” Atherosclerosis, vol. 265, Oct. 2017, pp. 60–70. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.08.003.

—. “The Impact of APOA5, APOB, APOC3 and ABCA1 Gene Polymorphisms on Ischemic Stroke: Evidence from a Meta-Analysis.” Atherosclerosis, vol. 265, Oct. 2017, pp. 60–70. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.08.003.

Aumont-Rodrigue, Gabriel, et al. “Apolipoprotein B Gene Expression and Regulation in Relation to Alzheimer’s Disease Pathophysiology.” Journal of Lipid Research, vol. 65, no. 11, Nov. 2024, p. 100667. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlr.2024.100667.

—. “Apolipoprotein B Gene Expression and Regulation in Relation to Alzheimer’s Disease Pathophysiology.” Journal of Lipid Research, vol. 65, no. 11, Oct. 2024, p. 100667. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlr.2024.100667.

Behbodikhah, Jennifer, et al. “Apolipoprotein B and Cardiovascular Disease: Biomarker and Potential Therapeutic Target.” Metabolites, vol. 11, no. 10, Oct. 2021, p. 690. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo11100690.

Beheshti, Sabina, et al. “Relationship of Familial Hypercholesterolemia and High Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol to Ischemic Stroke: Copenhagen General Population Study.” Circulation, vol. 138, no. 6, Aug. 2018, pp. 578–89. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.033470.

Benn, Marianne. “Apolipoprotein B Levels, APOB Alleles, and Risk of Ischemic Cardiovascular Disease in the General Population, a Review.” Atherosclerosis, vol. 206, no. 1, Sep. 2009, pp. 17–30. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.01.004.

Bergeron, Nathalie, et al. “Effects of Red Meat, White Meat, and Nonmeat Protein Sources on Atherogenic Lipoprotein Measures in the Context of Low Compared with High Saturated Fat Intake: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 110, no. 1, Jul. 2019, pp. 24–33. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqz035.

Calandra, Sebastiano, et al. “Mechanisms and Genetic Determinants Regulating Sterol Absorption, Circulating LDL Levels, and Sterol Elimination: Implications for Classification and Disease Risk.” Journal of Lipid Research, vol. 52, no. 11, Nov. 2011, pp. 1885–926. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R017855.

Chen, Yeda, et al. “Association Between Apolipoprotein B XbaI Polymorphism and Coronary Heart Disease in Han Chinese Population: A Meta-Analysis.” Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers, vol. 20, no. 6, Jun. 2016, pp. 304–11. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1089/gtmb.2015.0126.

Cicero, Arrigo F. G., et al. “Eulipidemic Effects of Berberine Administered Alone or in Combination with Other Natural Cholesterol-Lowering Agents. A Single-Blind Clinical Investigation.” Arzneimittel-Forschung, vol. 57, no. 1, 2007, pp. 26–30. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1296582.

Coto, Eliecer, et al. “The APOB Polymorphism Rs1801701 A/G (p.R3638Q) Is an Independent Risk Factor for Early-Onset Coronary Artery Disease: Data from a Spanish Cohort.” Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Diseases: NMCD, vol. 31, no. 5, May 2021, pp. 1564–68. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2021.02.010.

—. “The APOB Polymorphism Rs1801701 A/G (p.R3638Q) Is an Independent Risk Factor for Early-Onset Coronary Artery Disease: Data from a Spanish Cohort.” Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Diseases: NMCD, vol. 31, no. 5, May 2021, pp. 1564–68. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2021.02.010.

Devaraj, Sridevi, et al. “Biochemistry, Apolipoprotein B.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 2025. PubMed, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538139/.

Ghavami, Abed, et al. “Soluble Fiber Supplementation and Serum Lipid Profile: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.” Advances in Nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), vol. 14, no. 3, May 2023, pp. 465–74. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advnut.2023.01.005.

Haas, Blake E., et al. “Evidence of Mechanism How Rs7575840 Influences Apolipoprotein B Containing Lipid Particles.” Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, vol. 31, no. 5, May 2011, pp. 1201–07. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.224139.

Hart, Tricia L., et al. “Pecan Intake Improves Lipoprotein Particle Concentrations Compared with Usual Intake in Adults at Increased Risk of Cardiometabolic Diseases: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” The Journal of Nutrition, vol. 155, no. 5, May 2025, pp. 1459–65. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjnut.2025.03.014.

Hayat, Mahtaab, et al. “Genetic Associations between Serum Low LDL-Cholesterol Levels and Variants in LDLR, APOB, PCSK9 and LDLRAP1 in African Populations.” PLoS ONE, vol. 15, no. 2, Feb. 2020, p. e0229098. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229098.

Heeks, Liesl V., et al. “Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis-Related Cirrhosis in a Patient with APOB L343V Familial Hypobetalipoproteinaemia.” Clinica Chimica Acta, vol. 421, Jun. 2013, pp. 121–25. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2013.03.004.

Hubacek, J. A., et al. “Polygenic Hypercholesterolemia: Examples of GWAS Results and Their Replication in the Czech-Slavonic Population.” Physiological Research, vol. 66, no. Suppl 1, Apr. 2017, pp. S101–11. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.33549/physiolres.933580.

Jang, Shih-Jung, et al. “Pleiotropic Effects of APOB Variants on Lipid Profiles, Metabolic Syndrome, and the Risk of Diabetes Mellitus.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 23, no. 23, Nov. 2022, p. 14963. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232314963.

Li, Juan, et al. “Identification of the Flavonoid Luteolin as a Repressor of the Transcription Factor Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4α.” The Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 290, no. 39, Sep. 2015, pp. 24021–35. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M115.645200.

Lim, Younghyup, et al. “Apolipoprotein B Is Related to Metabolic Syndrome Independently of Low Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes.” Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 30, no. 2, 2015, p. 208. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2015.30.2.208.

Löffler, Tina, et al. “Impact of ApoB-100 Expression on Cognition and Brain Pathology in Wild-Type and hAPPsl Mice.” Neurobiology of Aging, vol. 34, no. 10, Oct. 2013, pp. 2379–88. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.04.008.

Niu, Caiqin, et al. “Associations of the APOB Rs693 and Rs17240441 Polymorphisms with Plasma APOB and Lipid Levels: A Meta-Analysis.” Lipids in Health and Disease, vol. 16, no. 1, Sep. 2017, p. 166. BioMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-017-0558-7.

Nuinoon, Manit, et al. “Association of CELSR2, APOB100, ABCG5/8, LDLR, and APOE Polymorphisms and Their Genetic Risks with Lipids among the Thai Subjects.” Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, vol. 30, no. 2, Feb. 2023, p. 103554. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2022.103554.

Pierdomenico, Maria, et al. “Effect of Citrus Bergamia Extract on Lipid Profile: A Combined in Vitro and Human Study.” Phytotherapy Research: PTR, vol. 37, no. 9, Sep. 2023, pp. 4185–95. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.7897.

Robinson, Jennifer G., et al. “Meta-Analysis of Comparison of Effectiveness of Lowering Apolipoprotein B versus Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Nonhigh-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in Randomized Trials.” The American Journal of Cardiology, vol. 110, no. 10, Nov. 2012, pp. 1468–76. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.07.007.

Rondanelli, M., et al. “Berberine Phospholipid Exerts a Positive Effect on the Glycemic Profile of Overweight Subjects with Impaired Fasting Blood Glucose (IFG): A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial.” European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, vol. 27, no. 14, Jul. 2023, pp. 6718–27. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202307_33142.

Sabatti, Chiara, et al. “Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Metabolic Traits in a Birth Cohort from a Founder Population.” Nature Genetics, vol. 41, no. 1, Jan. 2009, pp. 35–46. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.271.

Sun, Yan V., et al. “Effects of Genetic Variants Associated with Familial

Hypercholesterolemia on Low-Density Lipoprotein-Cholesterol Levels and

Cardiovascular Outcomes in the Million Veteran Program.” Circulation. Genomic and Precision Medicine, vol. 11, no. 12, Dec. 2018, p. e002192. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCGEN.118.002192.Yee, Jeong, et al. “APOB Gene Polymorphisms May Affect the Risk of Minor or Minimal Bleeding Complications in Patients on Warfarin Maintaining Therapeutic INR.” European Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 27, no. 10, Oct. 2019, pp. 1542–49. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0450-1.

Zheng, Chunyu, et al. “Food Intake Suppresses ApoB Secretion and Fractional Catabolic Rates in Humans.” Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, vol. 44, no. 2, Feb. 2024, pp. 435–51. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.123.319769.

Zhou, Juan, et al. “Effect of Lutein Supplementation on Blood Lipids and Advanced Glycation End Products in Adults with Central Obesity: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial.” Food & Function, vol. 16, no. 5, Mar. 2025, pp. 2096–107. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1039/d4fo05578k.

About the Author:

Debbie Moon is a biologist, engineer, author, and the founder of Genetic Lifehacks where she has helped thousands of members understand how to apply genetics to their diet, lifestyle, and health decisions. With more than 10 years of experience translating complex genetic research into practical health strategies, Debbie holds a BS in engineering from Colorado School of Mines and an MSc in biological sciences from Clemson University. She combines an engineering mindset with a biological systems approach to explain how genetic differences impact your optimal health.