Key takeaways:

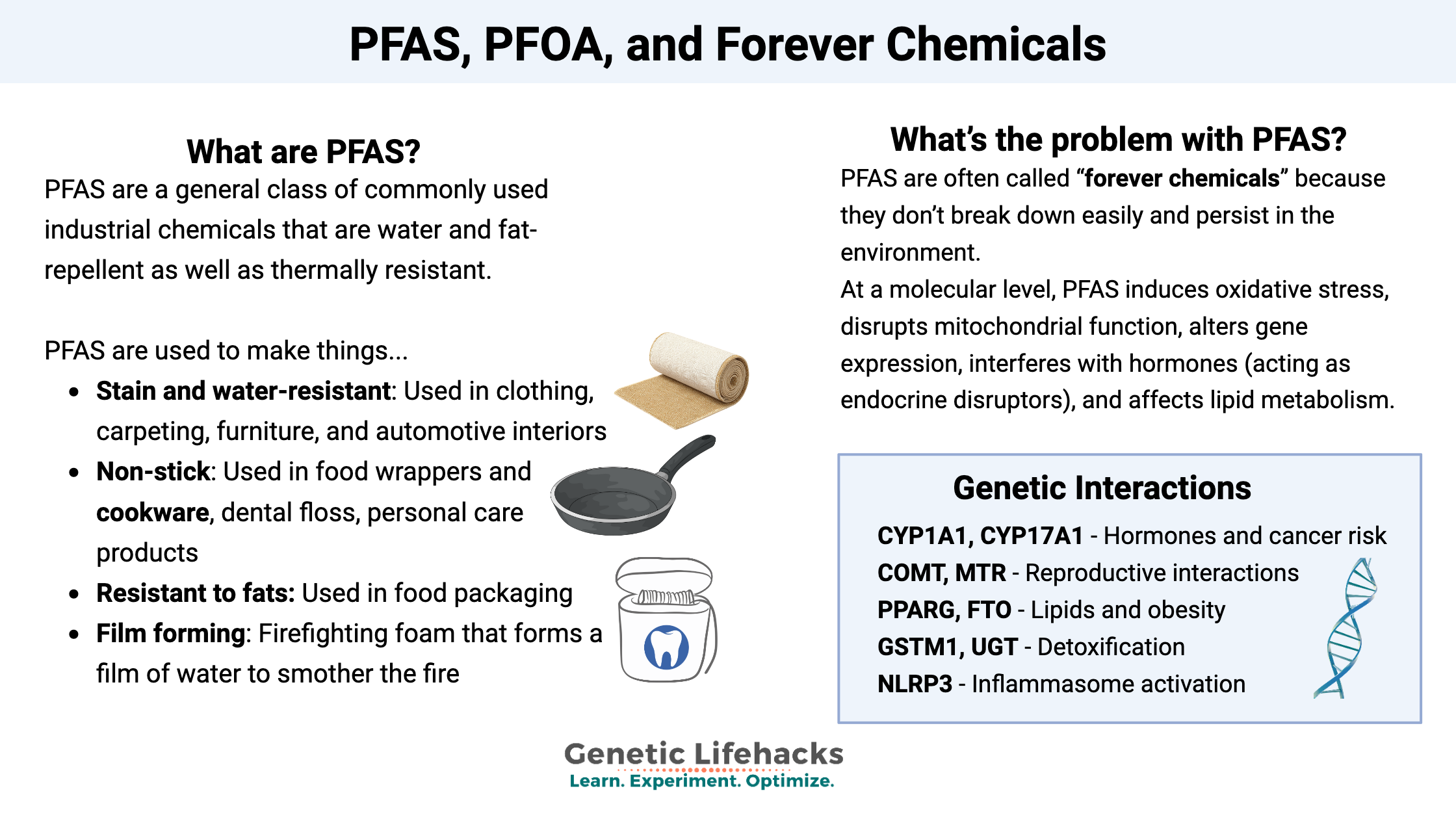

~ PFAS are persistent “forever chemicals” found in everyday products that are used to make products water-resistant, stain-resistant, and non-stick.

~ Research shows PFAS are associated with reproductive issues, immune suppression, thyroid dysfunction, fatty liver disease, asthma, high blood pressure, ADHD, and increased risk of certain cancers.

~At a cell level, PFAS causes oxidative stress, disrupts mitochondrial function, alters gene expression, interferes with hormones (acting as endocrine disruptors), and affects lipid metabolism.

~ Genetic variants can impact your risk of specific harms from PFAS and your ability to eliminate them from the body.

What are perfluorinated substances?

PFAS stands for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), which are a general class of commonly used industrial chemicals. The carbon-fluorine (C-F) bonds cause PFAS to be water and fat-repellent as well as thermally resistant.[ref]

PFAS is incorporated into materials to make them:

- Stain and water-resistant: Used in clothing, carpeting, furniture, and automotive interiors

- Non-stick: Used in food wrappers and cookware, dental floss, and personal care products

- Resistant to fats: Used in food packaging

- Film forming: Firefighting foam that forms a film of water to smother the fire

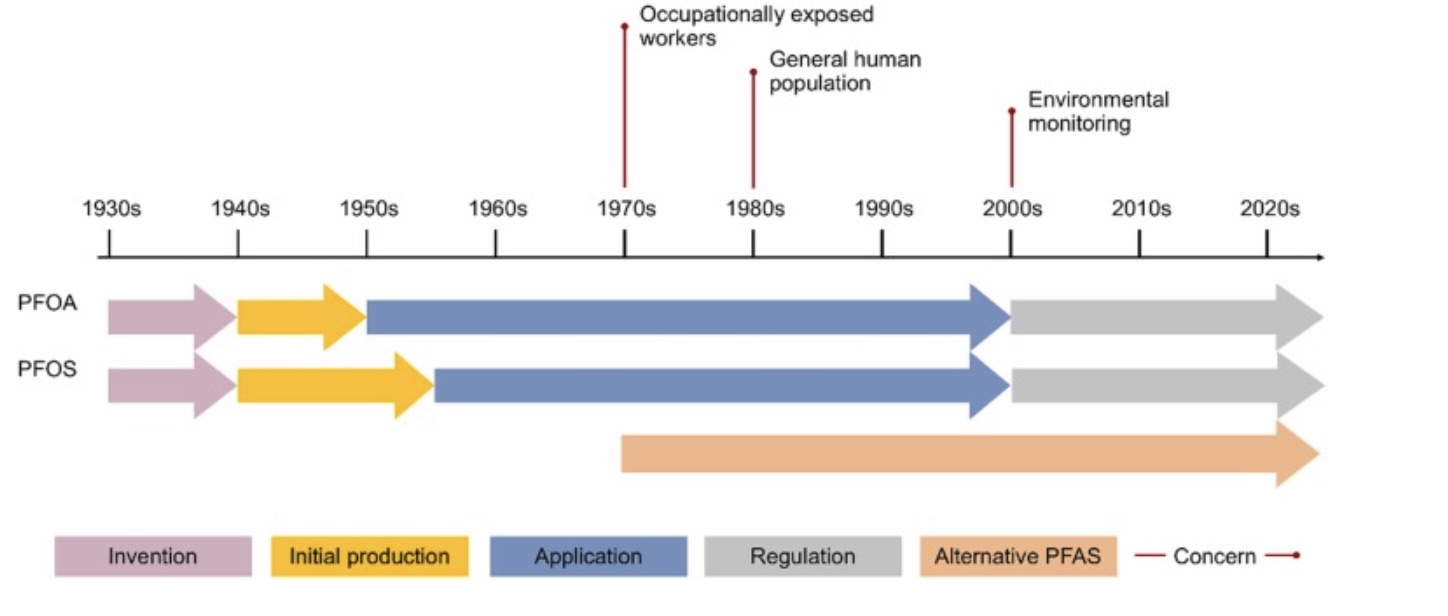

PFAS is an umbrella term that includes PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid), perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS), and other per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

Well-known uses of PFOA and PFOS were Teflon non-stick coatings and Scotchguard to make carpet and clothes stain-resistant. They were also widely used on food wrappers to make them resistant to water and oils. For the most part, PFOA and PFOS production has been phased out in the US due to the negative health effects seen in studies published in the early 2000s – 2010s.[ref]

The legacy PFOA, PFOS, and PFHxS compounds were replaced with shorter-chain or modified PFAS chemicals. Many products have changed to newer or different fluorinated substances over the past 15 years, but they are now being discovered to have many of the same negative health effects. A 2023 study showed that almost all of the replacement compounds directly affect the same biochemical pathways that were a concern with the legacy compounds.[ref]

GenX: One replacement for PFOA that you’ll often see is called GenX. About 15 years ago, in response to concerns about PFOA, DuPont introduced a PFOA-free Teflon coating, which they called GenX (not to be confused with kids in Generation X). A 2019 study from the Netherlands, where PFOA was phased out in 2012, showed that the newer GenX was ubiquitous in the environment (plants, animals, water) in areas near or downstream of a fluoropolymer plant.[ref]

In this article, I’ll refer to PFAS as a general term most of the time, but will get specific with the detoxification and excretion information. I’ll also point out whether a research study was funded by industry (when it is disclosed). Industry-funded studies aren’t necessarily always bad science, but you may want to take a closer look at how the study results are obtained.

What’s the problem with PFAS?

PFAS are usually referred to in news stories as “the forever chemical” because these substances don’t break down easily and persist in the environment. The perfluoroalkyl moiety (CnF2n+1−) is a carbon-fluorine bond in PFAS that makes them very chemically stable and resistant to degradation. The properties that make them very useful as chemicals – water and fat repellent, thermal resistance – also make them hang around for a long time.[ref] While PFOA and PFAS production have been mostly phased out in the US, the persistence in the environment means that in many areas, they are still found in the soil, drinking water, and game animals.[ref]

In addition to persisting in the environment, PFAS has a long half-life in the body. This is a problem because PFAS are linked to a number of potential health effects.

Let’s hit the highlights here. Click on the references to dive deeper into any of these health effects.

Reproductive issues:

A hundred or more studies show that PFOA, PFOS, and other PFAS cause problems with fertility and birth outcomes, increase the risk of PCOS, and premature ovarian failure.[ref] A recent study in women undergoing IVF showed that PFAS is able to cross into the follicular fluid in the ovaries, with 88% of samples showing the newer GenX substance.[ref] Animal studies that differentiate between the original PFOA and PFOS compared to the newer, shorter-chain PFAS indicate that the older PFAS types were likely more of a problem for ovarian follicle cells.[ref]

Lung function:

Epidemiological studies show increased lung problems with higher PFAS levels. A recent study explains why: PFOS and PFOA exposure significantly downregulated surfactant protein B, causing impaired lung function. Specifically, PFOA caused hypermethylation of HSD17B1 (hydroxysteroid 17-beta dehydrogenase 1), which in turn caused a decrease in surfactant protein B, which is a substance that lines the alveoli (tiny air sacs) in the lungs and prevents them from collapsing when you exhale.[ref]

Immune suppression:

A number of studies show that higher levels of PFAS correlate with a reduced immune response to vaccinations, which is a direct way to measure suppressed immune response.[ref]

Thyroid:

Higher levels of PFAS are associated with increased TSH and hypothyroidism.[ref]

Fatty liver (NAFLD, MAFLD):

Studies show that PFAS exposure increases lipids in the liver, leading to fatty liver in some individuals. A recent metabolomics study showed that PFAS downregulated the gene expression of NUDT7, which is a key for lipid regulation in the liver. This gene expression change was found at levels that humans are regularly exposed to.[ref]

Hormones and obesity:

PFAS act as an endocrine disruptor, altering hormone secretions and menstrual cycles in women.[ref] Higher levels are associated with volume of uterine fibroids.[ref]

Asthma:

Studies show that certain types of PFAS are associated with an increased risk of asthma in children. Higher PFAS levels correlate to more asthma attacks as well.[ref][ref]

Gut barrier, fat accumulation:

Another connection between higher PFAS levels, obesity, and insulin resistance is seen in the gut. A 2024 study looked at how PFAS and PFAS in combination with BPA and other common environmental toxins affected the gut microbiome. The researchers found that higher PFAS plus other environmental toxicants cause a shift in the composition of the microbiome in ways that alter secondary bile acids and promote obesity and insulin resistance.[ref]

Neurodegeneration:

PFAS accumulates in the brain, but the newer, shorter-chain versions don’t cross into the brain as effectively as the older PFOA and PFOS types.[ref]

High blood pressure:

A meta-analysis of 14 human studies showed that exposure to general PFAS or PFOS increased the risk of hypertension. [ref]

Neurodevelopmental problems:

PFAS can cross the blood-brain barrier, and animal studies show that it accumulates in the brain at higher levels. Some studies show that higher levels of PFAS are associated with increased risk of ADHD.[ref] However, not all studies agree. A meta-analysis conducted by Chinese researchers found that maternal PFAS exposure was unlikely to cause ADHD in their children.[ref]

A 2025 study looked at PFAS exposure in utero in the first and second trimester. The results showed that higher PFAS exposure doubled the risk of developmental delays at 6 and 12 months of age. However, the risk was mitigated by increased DHA consumption during breastfeeding.[ref]

Animal studies show that certain types of PFAS interact with FOLR2 (folate receptor beta) and cause social deficits.[ref] A 2024 study in Shanghai found that prenatal PFOA exposure increased autistic traits in children at the age of 4 in those with genetic risk factors. The risk was mitigated by higher folate intake.[ref]

Related article: FOLR1 and FOLR2

Mast cell activation:

Animal studies and cell studies show that PFOS, a type of PFAS, causes mast cell activation.[ref] This is likely one of several mechanisms connecting higher PFAS levels and increased asthma risk.

Carcinogenic (Cancer-causing):

Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) was recently classified by the IARC as a Class 1 carcinogen. PFOS is classified as a Class 2B possible carcinogen.[ref]

How big a worry is PFAS for cancer? A large 2025 study in the US looked at levels of PFAS in public water systems compared to county-level cancer incidence. After adjusting for other covariates that also cause cancer, researchers found that higher PFAS levels are associated with an increased relative risk of thyroid cancer, bladder cancer, brain cancer, and leukemia. The researchers estimated up to ~6800 cases of cancer per year were caused by PFAS (not a large number, in the context of the million or so cases of cancer each year in the US).[ref]

Multiple Sclerosis:

A new study found that exposure to PFAS, combined with genetic susceptibility, significantly increased the risk of multiple sclerosis. [ref]

Related article: Multiple Sclerosis: Genetic Factors and Susceptibility to MS

Mechanisms of action: Why is PFAS harmful to health?

While PFAS exposure is linked to numerous health changes, the association studies don’t really explain why it’s a problem. So let’s take a look at the studies on what is going on biochemically from PFAS.

Here are some of the actions that go on at a cellular level:

Oxidative stress:

Recent studies show that PFAS induces oxidative stress by increasing ROS levels, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction. PFOA alters the KEAP-NFE2L2 signaling pathways (Nrf2 pathway). A study in mesenchymal stem cells showed that PFOA accelerates aging and impairs regeneration.[ref] Animal studies show that PFAS downregulates gene expression of antioxidant defense, such as superoxide dismutase, CAT, and glutathione-related detoxification genes. These experiments were done with the newer alternative PFAS substances that replaced the legacy PFOA and PFAS.[ref]

Lipid perturbations:

In mice, PFAS alters fatty acid oxidation genes, lipid transport genes, and bile acid synthesis.[ref] Studies also show that PFAS alters gene expression for PPAR and other lipid-related genes.[ref]

Changes to gene transcription, hormones:

A study using ovarian cells exposed to realistic levels of PFAS found changes to gene expression that caused altered steroid hormone synthesis, including increased FSH and progesterone.[ref]

Specifically, exposure to PFAS causes hypermethylation of 17β-HSD1, which is the enzyme that converts estrone (E1) to estradiol (E2). This is one way that PFAS exposure causes changes to reproduction for women. Hypermethylation causes decreased expression of the 17β-HSD1, which is also involved in testosterone conversion, to a lesser extent than the effect on estrogen in humans. A complete deficiency in 17β-HSD1 during development causes XY (male) individuals to have more female-appearing genitalia at birth, which can change then during puberty. (To be clear – I’m not saying that PFAS hypermethylation of 17β-HSD1 causes males to appear as females at birth. That is just an example of what severe deficiency from genetic mutations in the gene can cause, given here as a way to explain the role of the enzyme in male development.)[ref][ref]

In addition to the methylation changes to hormone-related genes, PFAS exposure has a broader effect on methylation of other genes, including genes related to cardiovascular health, cognitive function, and kidney function. [ref][ref] Changes to gene expression are a more subtle way that an environmental exposure can change susceptibility to health outcomes. Researchers have found that prenatal exposure to PFAS causes increased 5-methylcytosine methylation, which is a type of methylation that decreases gene expression more permanently than other methylation sites. These methylation changes in utero can persist throughout life.[ref]

Active Vitamin A synthesis:

Vitamin A in the active retinol form is important for gene expression during development, immune function, and overall health. Multiple animal studies show that PFAS can interfere with retinol synthesis, transport, and metabolism.[ref]

Genotoxicity:

The epidemiological studies do show that PFAS exposure likely increases the relative risk of certain types of cancers. Genotoxicity studies show that PFOS increases micronuclei formation, which is a marker of errors in cell division.[ref]

Cell proliferation:

PFAS has also been shown to cause gene expression changes that promote cell proliferation and migration.[ref]

Inflammasome (NLRP3) activation:

Studies show that PFOA and PFOS alone or in a mixture will prime and activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. It is thought that this is one factor that increases lung problems from PFAS.[ref]

Related article: NLRP3 inflammasome and genetic susceptibility

Changes to circadian rhythm:

Animal studies also show that PFAS exposure changes gene expression for circadian rhythm genes.[ref]

Exposure routes:

There are multiple ways that we get PFAS into the body, including oral, transdermal, and inhalation.

Oral exposure routes include drinking water containing PFAS as well as eating foods or consuming drinks with PFAS. PFAS can also be inhaled (e.g. dust) or absorbed transdermally through your skin.

A 2024 study in children found that PFAS levels were higher in those who drank tea, ate hot dogs, or ate other processed meats. Another 2023 study in children found that those eating more whole foods, fiber, fruits, and vegetables had lower levels.[ref][ref] Of note, all the participants had detectable PFAS. This is generally true for most studies — pretty much everyone has a little PFAS in them.

One problem is that conventional water treatment methods don’t remove PFAS, and they get recycled into the biosludge.[ref] In the US and a few other countries, biosludge from wastewater treatment plants gets spread on fields. This then contaminates groundwater, plants, livestock, and rivers.

Drinking water limits:

In 2022, the US EPA recommended stricter standards for PFAS with limits of 0.004 ng/L for PFOA and 0.02 ng/L for PFOS. Prior to this, there was a 70 ng/L lifetime drinking water health advisory level set in 2016.[ref]

Elimination of PFAS:

OK – so we have looked at the long-term health effects of PFAS, as well as the mechanisms and pathways affected. Now let’s take a look at how the body gets rid of the forever chemical.

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related articles and topics:

BPA and BPS: How Your Genes Influence Bisphenol Detoxification