Key takeaways:

~ GLP-1 receptor agonists (e.g., semaglutide, liraglutide) are now approved for weight loss for teens and adults.

~ These medications work by binding to the GLP-1 receptor and reducing appetite.

~ Genetic variants can affect the response to GLP-1 agonists for weight loss.

Losing weight can be challenging for most people. It is easy to become frustrated and lose motivation for a specific diet or exercise program. Cravings can torpedo your best-laid eating plans. The GLP-1 agonists seem to be effective because they don’t rely on willpower or require a specific diet – instead, the weekly injections just make you feel full.

Members will see their genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

GLP-1 agonists: Who do they work for?

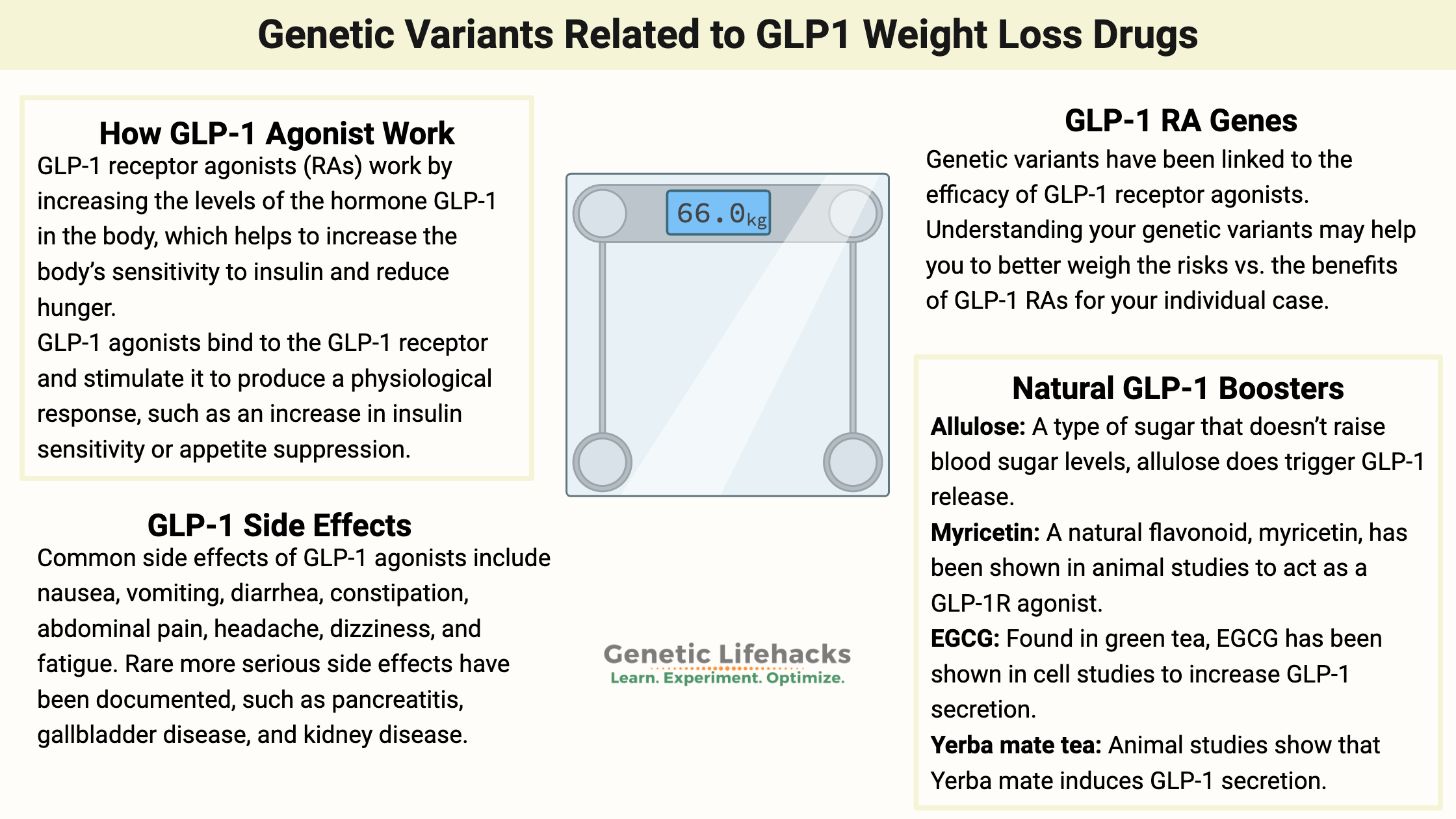

GLP-1 receptor agonists work by increasing the levels of the hormone GLP-1 in the body, which helps to increase the body’s sensitivity to insulin and reduce hunger.

An agonist is a type of drug or other agent that binds to a receptor on a cell and triggers a physiological response. Agonists stimulate receptors to produce an action, while antagonists block or inhibit the action of agonists.

GLP-1 agonists bind to the GLP-1 receptor and stimulate it to produce a physiological response, such as an increase in insulin sensitivity or appetite suppression.

Two GLP-1 receptor agonists (RAs) currently approved for weight loss are liraglutide and semaglutide. These drugs are typically prescribed to adults, and now teens, who are obese (BMI above 30).

Interestingly, GLP-1 RAs work better for weight loss in people without diabetes. Clinical trials show that semaglutide works a little bit better than liraglutide for most people in promoting weight loss.[ref]

What do GLP-1 receptor agonists do?

GLP-1RAs work by increasing the levels of the hormone glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) in the body.

GLP-1 increases the body’s sensitivity to insulin, the hormone responsible for controlling blood sugar levels. GLP 1 agonists can also help reduce hunger and slow down the rate of food digestion, making them an important tool in weight management.

GLP-1 is released in response to food intake. When you eat carbohydrates or certain proteins, the stomach releases the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) hormone, which triggers the release of insulin from the pancreas. This helps to regulate blood sugar levels in the body. GLP-1 also helps to suppress appetite and slow down the rate of food digestion, which can lead to weight loss.

The receptor for GLP-1 is the GLP-1 receptor (GLP1R), a G-protein coupled receptor. The GLP-1 receptor is a type of cell surface receptor that binds to GLP-1, triggering a signaling cascade that leads to various effects, including the stimulation of insulin secretion, the inhibition of gastric emptying, and the promotion of satiety.

How does a GLP-1 agonist work for weight loss

By binding to the GLP-1 receptor, GLP-1 RAs mimic the effects of having eaten and released GLP1. In other words, you’ll feel full and won’t be driven to eat as much.

GLP-1 receptors are located in the brain, and GLP1 is created in the brain in preproglucagon neurons. Researchers have found that these preproglucagon neurons are naturally activated, specifically after large meals. But, a recent mouse study showed that semaglutide doesn’t really target these preproglucagon neurons and instead acts more on the peripheral systems.[ref]

GLP-1 receptors are also found on pancreatic beta cells, triggering insulin release. It also targets other cells in the pancreas to stop the glucagon signal for generating glucose in the liver.[ref]

In clinical trials, GLP-1 RAs improved lipid profiles, increased satiety and slower gastric emptying, reduced inflammation, and had neuroprotective effects.[ref] The slowing of gastric emptying and reducing inflammation may also play a role in weight loss – along with the decrease in appetite.

Which GLP-1 Agonists are Approved for Weight Loss?

There are currently two GLP-1 receptor agonists approved for weight loss: liraglutide and semaglutide.

Liraglutide is an injectable drug taken once a day, while semaglutide is an injectable drug taken once a week.

Who is Eligible for GLP-1 Agonists for Weight Loss?

GLP-1 agonists are typically prescribed to adults over the age of 18 who are overweight or obese with a body mass index (BMI) above 30. However, these drugs may also be prescribed to adults with a BMI of 27 or higher if they have other health conditions such as type 2 diabetes or high cholesterol.

Talk to your doctor to see if you are eligible and whether it is the best option for you.

The FDA also just approved semaglutide for adolescents (ages 12 and up) with an initial BMI at or above the 95th percentile for their age and sex.[ref]

Clinical trial in adolescents:

A recent clinical trial showed that teens who were overweight or obese also lost weight on semaglutide. The trial ran for a little over a year and showed an average decrease in BMI of 16% (compared to 0.6% for placebo). To put that into perspective, if starting BMI was 32, a 16% reduction would bring it down to 27. Gastrointestinal adverse events were reported in 62% of the group taking semaglutide, compared to 42% in the placebo group.[ref]

GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Genotype Report:

Members: Log in to see your data below.

Not a member? Join here.

Why is this section is now only for members? Here’s why…

Lifehacks:

The GLP-1 receptor agonists are prescription medications. Talk with your doctor and see what your insurance will cover. The out-of-pocket cost without insurance is listed as around $1600/month, so this is definitely something you want to investigate thoroughly and make sure your insurance will cover it.

If you don’t have a GP, several online telemedicine websites now offer GLP-1 agonists for weight loss. There is a cost for the initial online exam, where you’ll video chat with a medical professional, and then some charge a monthly fee for follow-ups and for the prescription.

What about safety? Are GLP-1 agonists safe for everyone?

Although this type of medication is FDA-approved, that doesn’t mean it is safe for everyone

Side effects associated with GLP-1 agonists include:

Common side effects of GLP-1 agonists include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain, headache, dizziness, and fatigue. Most gastrointestinal side effects occur during the first month. In rare cases, GLP-1 agonists may cause serious side effects, including allergic reactions, pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, and kidney disease.[ref][ref]

Obviously, talk with your doctor about the risks vs. benefits of GLP-1RAs for your specific situation.

No impact on bone fractures:

If osteoporosis is a concern, the GLP-1 receptor agonists were shown not to increase fracture rates.[ref]

Benefits for CVD:

In a huge cardiovascular disease study, GLP-1 RAs were shown to be associated with a lower risk of heart attacks and strokes.[ref]

Works best with Exercise:

A randomized clinical trial found that GLP-1 RAs work best for weight loss when combined with exercise. They compared exercise alone, exercise plus liraglutide, or liraglutide alone in people without diabetes.[ref]

9 Natural supplements and diet changes that increase GLP-1

Related Articles and Topics:

Histamine intolerance and alcohol:

Learn why drinking alcohol can exacerbate histamine intolerance or mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS).

Hacking BDNF for weight loss

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a fascinating growth hormone that performs many functions in our brain. Its involvement helps to support neurons and neuronal growth. In addition, it plays a role in long-term memory — and it also is important in obesity.

Which type of choline works best with your genes?

Choline is an often neglected nutrient essential to a healthy diet. Your genes are important in how much and which types of choline you need.

Genetic Links to High Uric Acid and Gout

High uric acid levels can cause the pain and inflammation seen in gout. Find out how your genetic variants influence your uric acid levels and gout risk.

References:

Brierley, Daniel I., et al. “Central and Peripheral GLP-1 Systems Independently Suppress Eating.” Nature Metabolism, vol. 3, no. 2, Feb. 2021, pp. 258–73. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-021-00344-4.

Chedid, V., et al. “Allelic Variant in the Glucagon-like Peptide 1 Receptor Gene Associated with Greater Effect of Liraglutide and Exenatide on Gastric Emptying: A Pilot Pharmacogenetics Study.” Neurogastroenterology and Motility: The Official Journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society, vol. 30, no. 7, July 2018, p. e13313. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13313.

de Graaf, Chris, et al. “Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 and Its Class B G Protein–Coupled Receptors: A Long March to Therapeutic Successes.” Pharmacological Reviews, vol. 68, no. 4, Oct. 2016, pp. 954–1013. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.115.011395.

de Luis, Daniel Antonio, Gonzalo Diaz Soto, et al. “Evaluation of Weight Loss and Metabolic Changes in Diabetic Patients Treated with Liraglutide, Effect of RS 6923761 Gene Variant of Glucagon-like Peptide 1 Receptor.” Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications, vol. 29, no. 4, 2015, pp. 595–98. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.02.010.

de Luis, Daniel Antonio, Hilda F. Ovalle, et al. “Role of Genetic Variation in the Cannabinoid Receptor Gene (CNR1) (G1359A Polymorphism) on Weight Loss and Cardiovascular Risk Factors after Liraglutide Treatment in Obese Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Type 2.” Journal of Investigative Medicine: The Official Publication of the American Federation for Clinical Research, vol. 62, no. 2, Feb. 2014, pp. 324–27. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.2310/JIM.0000000000000032.

Ding, Weiyue, et al. “Meta-Analysis of Association between TCF7L2 Polymorphism Rs7903146 and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.” BMC Medical Genetics, vol. 19, Mar. 2018, p. 38. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-018-0553-5.

Dong, Shichao, and Chuan Sun. “Can Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists Cause Acute Kidney Injury? An Analytical Study Based on Post-Marketing Approval Pharmacovigilance Data.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 13, 2022, p. 1032199. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1032199.

Florez, Jose C., et al. “TCF7L2 Polymorphisms and Progression to Diabetes in the Diabetes Prevention Program.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 355, no. 3, July 2006, pp. 241–50. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa062418.

Geraedts, Maartje C. P., et al. “Direct Induction of CCK and GLP-1 Release from Murine Endocrine Cells by Intact Dietary Proteins.” Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, vol. 55, no. 3, Mar. 2011, pp. 476–84. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201000142.

Hidayat, K., et al. “Risk of Fracture with Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitors, Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists, or Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors in Real-World Use: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies.” Osteoporosis International: A Journal Established as Result of Cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA, vol. 30, no. 10, Oct. 2019, pp. 1923–40. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-019-04968-x.

Hira, Tohru, et al. “Improvement of Glucose Tolerance by Food Factors Having Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Releasing Activity.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 22, no. 12, June 2021, p. 6623. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22126623.

Jensterle, Mojca, Manfredi Rizzo, et al. “Efficacy of GLP-1 RA Approved for Weight Management in Patients With or Without Diabetes: A Narrative Review.” Advances in Therapy, vol. 39, no. 6, 2022, pp. 2452–67. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-022-02153-x.

Jensterle, Mojca, Boštjan Pirš, et al. “Genetic Variability in GLP-1 Receptor Is Associated with Inter-Individual Differences in Weight Lowering Potential of Liraglutide in Obese Women with PCOS: A Pilot Study.” European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, vol. 71, no. 7, July 2015, pp. 817–24. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-015-1868-1.

Kadrić, Selma Imamović, et al. “Pharmacogenetics of New Classes of Antidiabetic Drugs.” Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences, vol. 21, no. 6, Dec. 2021, pp. 659–71. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.17305/bjbms.2021.5646.

Li, Ying, et al. “Myricetin: A Potent Approach for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes as a Natural Class B GPCR Agonist.” The FASEB Journal, vol. 31, no. 6, June 2017, pp. 2603–11. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.201601339R.

Lin, Donna Shu-Han, et al. “The Efficacy and Safety of Novel Classes of Glucose-Lowering Drugs for Cardiovascular Outcomes: A Network Meta-Analysis of Randomised Clinical Trials.” Diabetologia, vol. 64, no. 12, Dec. 2021, pp. 2676–86. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-021-05529-w.

Liu, Lulu, et al. “Association between Different GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and Gastrointestinal Adverse Reactions: A Real-World Disproportionality Study Based on FDA Adverse Event Reporting System Database.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 13, 2022, p. 1043789. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1043789.

Lundgren, Julie R., et al. “Healthy Weight Loss Maintenance with Exercise, Liraglutide, or Both Combined.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 384, no. 18, May 2021, pp. 1719–30. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2028198.

Maselli, Daniel, et al. “Effects of Liraglutide on Gastrointestinal Functions and Weight in Obesity: A Randomized Clinical and Pharmacogenomic Trial.” Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), vol. 30, no. 8, Aug. 2022, pp. 1608–20. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23481.

Pham, Hung, et al. “A Bitter Pill for Type 2 Diabetes? The Activation of Bitter Taste Receptor TAS2R38 Can Stimulate GLP-1 Release from Enteroendocrine L-Cells.” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, vol. 475, no. 3, July 2016, pp. 295–300. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.04.149.

Stolerman, E. S., et al. “TCF7L2 Variants Are Associated with Increased Proinsulin/Insulin Ratios but Not Obesity Traits in the Framingham Heart Study.” Diabetologia, vol. 52, no. 4, Apr. 2009, pp. 614–20. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-009-1266-2.

Sun, Siyu, et al. “Oral Berberine Ameliorates High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity by Activating TAS2Rs in Tuft and Endocrine Cells in the Gut.” Life Sciences, vol. 311, no. Pt A, Dec. 2022, p. 121141. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2022.121141.

van der Kroef, Sabrina, et al. “Association between the Rs7903146 Polymorphism in the TCF7L2 Gene and Parameters Derived with Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Individuals without Diabetes.” PLoS ONE, vol. 11, no. 2, Feb. 2016, p. e0149992. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0149992.

Weghuber, Daniel, et al. “Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adolescents with Obesity.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 387, no. 24, Dec. 2022, pp. 2245–57. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2208601.

Wegovy OK’d for Teens With Obesity. 29 Dec. 2022, https://www.medpagetoday.com/pediatrics/obesity/102430.

Wessel, Jennifer, et al. “Low-Frequency and Rare Exome Chip Variants Associate with Fasting Glucose and Type 2 Diabetes Susceptibility.” Nature Communications, vol. 6, Jan. 2015, p. 5897. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6897.

Yue, Xiao, et al. “Berberine Activates Bitter Taste Responses of Enteroendocrine STC-1 Cells.” Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, vol. 447, no. 1–2, Oct. 2018, pp. 21–32. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-018-3290-3.