Sore muscles after a hard workout is often the first thing that comes to mind when thinking of lactate. The classic view of lactate is that it is a metabolic waste product that accumulates in your muscles. However, this is far from the truth when it comes to this fundamental cellular compound.

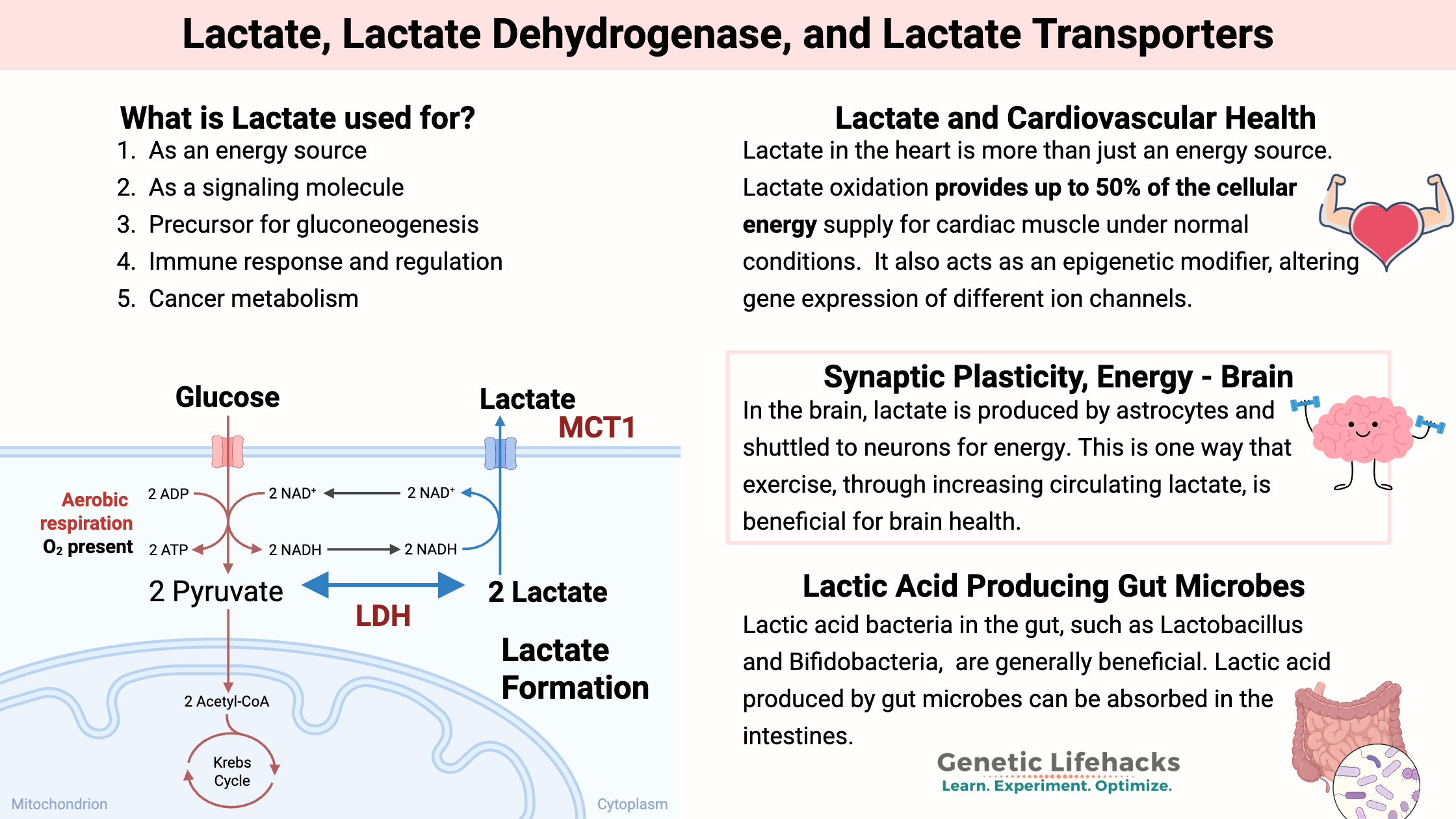

Lactate is formed when cells create ATP from glucose. Rather than being a waste product, lactate is a major source of energy in the body. It is now considered a glucose-sparing molecule that can fuel the brain or muscles.

Let’s dive into the details on what lactate is used for, how lactate is formed, how it moves around in the body, and how your genes may influence cellular energy from lactate.

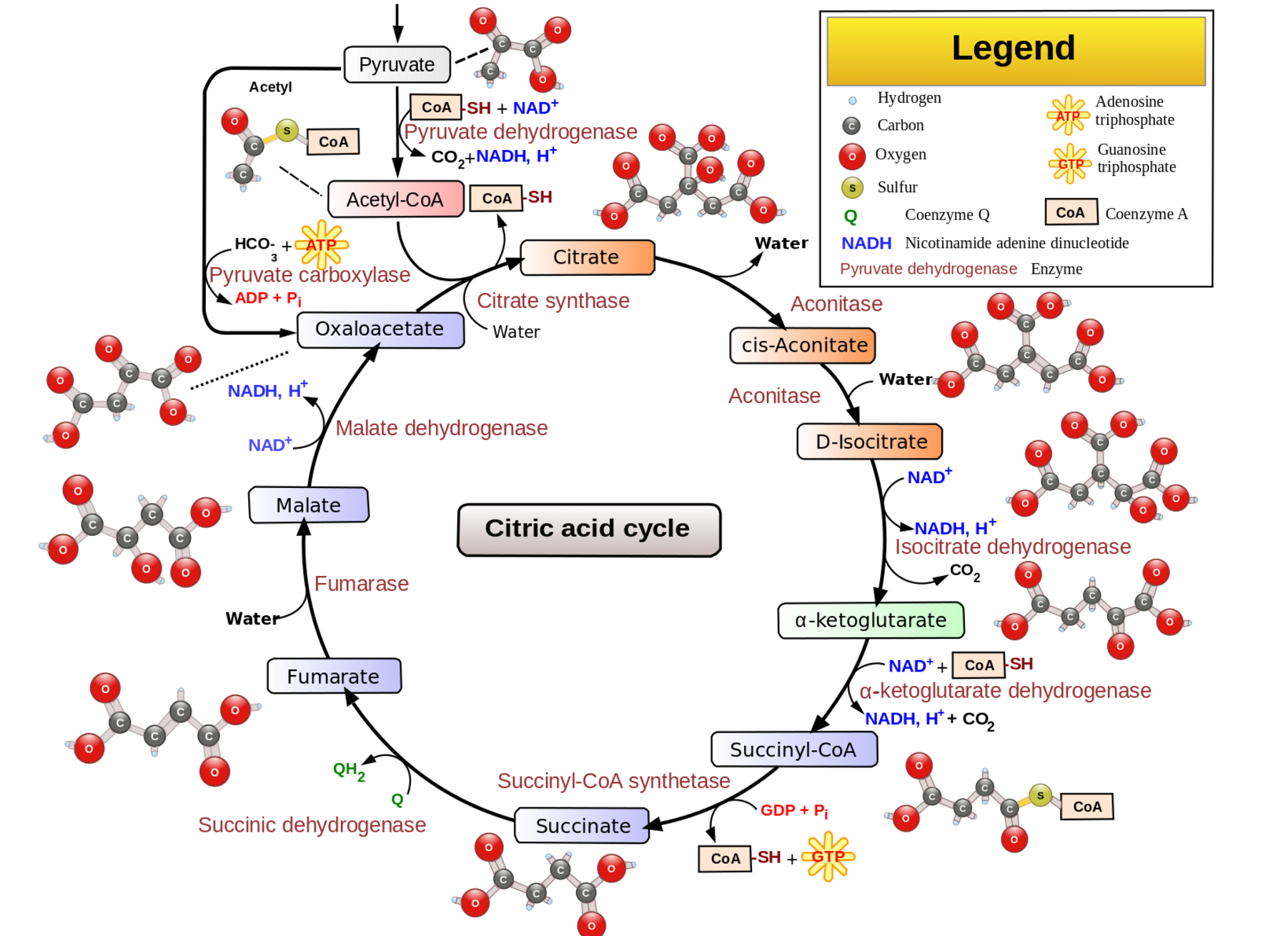

Cells make ATP to store energy for use in many different cellular reactions. In the cytosol, ATP can be generated by breaking down glucose into two molecules of pyruvate and NADH. This process produces two ATP molecules and is called glycolysis.

Cells can also produce a lot of ATP in the mitochondria through the Krebs cycle, also called the citric acid cycle, and through oxidative phosphorylation. The Krebs cycle uses the pyruvate from the cytosolic breakdown of glucose.

Isotope tracing shows that cells balance out the uptake of glucose, its conversion to pyruvate (glycolysis), and then either mitochondrial ATP production or lactate synthesis.

If the mitochondria aren’t able to handle or don’t need pyruvate for the Krebs cycle, it converts to lactate, which can then be transported out of the cell and used elsewhere in the body. When a cell needs more ATP from the mitochondria, lactate can be transported into cells to be converted to pyruvate and then ATP in the mitochondria.[ref]

The interconversion of lactate and pyruvate by LDH is driven by the lactate concentration. There is usually 20X more lactate than pyruvate in the cytosol.

This flux of pyruvate to lactate means that glycolysis can occur in the cytosol when glucose is available, but it doesn’t have to be coupled with mitochondrial ATP production. In other words, without the ability to convert pyruvate to lactate, every pyruvate molecule would need to be converted to ATP in the mitochondria. Lactate allows that to be decoupled.

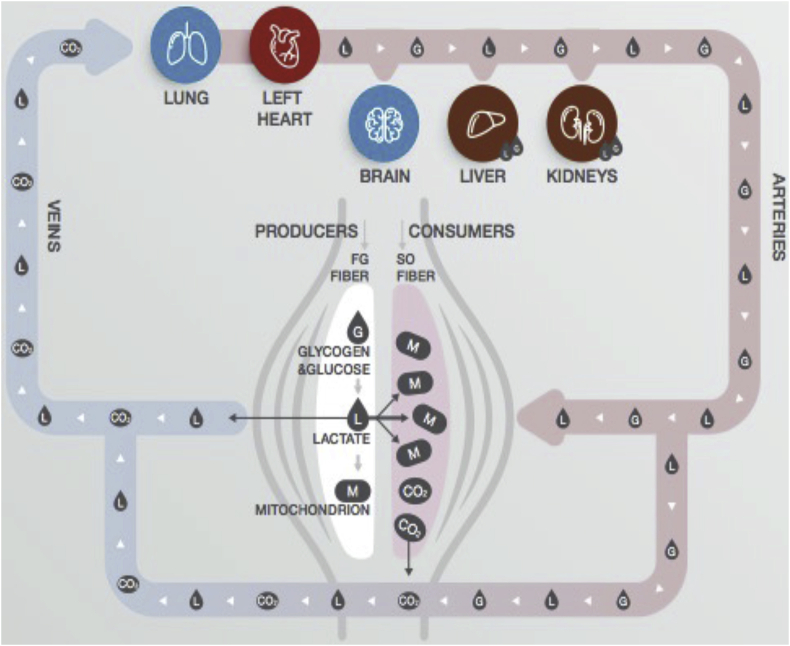

Excess lactate can be transported out of cells and either into nearby cells or it can circulate. For example, in skeletal muscles, lactate is produced when exercising and is exported for use as energy in other muscle cells. There is cell-to-cell shuttling of lactate, and it can also circulate for use in other organs.[ref]

Circulating lactate acts as a signaling molecule in the brain, heart, and adipose tissue. The GPR81 receptor (HCAR1 gene) is stimulated by lactate. It acts as a metabolic sensor to regulate several systems in the body based on energy metabolism.[ref] In adipose tissue, higher lactate levels inhibit lipolysis.[ref][ref]

In the brain, lactate binding with CGRP receptors is believed to play a role in regulating fat metabolism during exercise.[ref] The GPR81 receptor also plays a role in protecting the brain during times of energy deficit, such as during a stroke or brain injury.[ref]

In the heart, lactate acts as an energy molecule, especially during exercise or exertion. Recent research also shows that in heart disease, lactate levels may rise in the heart muscle and accumulate, causing disturbances in the physiology of how the heart contracts.[ref]

Aveseh, Malihe, et al. “Lactate Entrance into the Brain Facilities Adipose Tissue Lipolysis during Exercise via Circulating Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide.” Archives of Physiology and Biochemistry, vol. 130, no. 6, Dec. 2024, pp. 790–99. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1080/13813455.2023.2283684.

Brooks, George A. “Lactate as a Fulcrum of Metabolism.” Redox Biology, vol. 35, Feb. 2020, p. 101454. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2020.101454.

Cascella, Raffaella, et al. “Uncovering Genetic and Non-Genetic Biomarkers Specific for Exudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Significant Association of Twelve Variants.” Oncotarget, vol. 9, no. 8, Dec. 2017, pp. 7812–21. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.23241.

Colucci, Anna Clara Machado, et al. “History and Function of the Lactate Receptor GPR81/HCAR1 in the Brain: A Putative Therapeutic Target for the Treatment of Cerebral Ischemia.” Neuroscience, vol. 526, Aug. 2023, pp. 144–63. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2023.06.022.

Cupeiro, Rocío, Domingo González-Lamuño, et al. “Influence of the MCT1-T1470A Polymorphism (Rs1049434) on Blood Lactate Accumulation during Different Circuit Weight Trainings in Men and Women.” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, vol. 15, no. 6, Nov. 2012, pp. 541–47. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2012.03.009.

Cupeiro, Rocío, Pedro J. Benito, et al. “The Association of SLC16A1 ( MCT1 ) Gene Polymorphism with Body Composition Changes during Weight Loss Interventions: A Randomized Trial with Sex-Dependent Analysis.” Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, vol. 50, Jan. 2025, pp. 1–12. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2024-0246.

Ding, Zhaokun, and Youqing Xu. “Lactic Acid Is Absorbed from the Small Intestine of Sheep.” Journal of Experimental Zoology Part A: Comparative Experimental Biology, vol. 295A, no. 1, Jan. 2003, pp. 29–36. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1002/jez.a.10212.

Eseberri, Itziar, et al. “Effects of Physiological Doses of Resveratrol and Quercetin on Glucose Metabolism in Primary Myotubes.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 22, no. 3, Jan. 2021, p. 1384. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22031384.

Felmlee, Melanie A., et al. “Monocarboxylate Transporters (SLC16): Function, Regulation, and Role in Health and Disease.” Pharmacological Reviews, vol. 72, no. 2, Apr. 2020, pp. 466–85. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.119.018762.

Guo, Xu, et al. “Genetic Variations in Monocarboxylate Transporter Genes as Predictors of Clinical Outcomes in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer.” Tumour Biology: The Journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine, vol. 36, no. 5, May 2015, pp. 3931–39. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13277-014-3036-0.

Heemskerk, Mattijs M., et al. “Reanalysis of mGWAS Results and in Vitro Validation Show That Lactate Dehydrogenase Interacts with Branched-Chain Amino Acid Metabolism.” European Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 24, no. 1, Jan. 2016, pp. 142–45. www.nature.com, https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2015.106.

Heller, M. D., and F. Kern. “Absorption of Lactic Acid from an Isolated Intestinal Segment in the Intact Rat.” Experimental Biology and Medicine, vol. 127, no. 4, Apr. 1968, pp. 1103–06. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.3181/00379727-127-32882.

Hu, Jiun-Ruey, et al. “Effects of Carbohydrate Quality and Amount on Plasma Lactate: Results from the OmniCarb Trial.” BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care, vol. 8, no. 1, Aug. 2020, p. e001457. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-001457.

Łacina, Piotr, et al. “BSG and MCT1 Genetic Variants Influence Survival in Multiple Myeloma Patients.” Genes, vol. 9, no. 5, Apr. 2018, p. 226. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/genes9050226.

LDlink | Home. https://ldlink.nih.gov/?var=rs1049434&pop=CEU&genome_build=grch37&r2_d=r2&window=500000&collapseTranscript=true&annotate=forge&tab=ldproxy. Accessed 13 Jan. 2026.

Lee, Jinu, et al. “The Genetic Variation in Monocarboxylic Acid Transporter 2 (MCT2) Has Functional and Clinical Relevance with Male Infertility.” Asian Journal of Andrology, vol. 16, no. 5, 2014, pp. 694–97. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.4103/1008-682X.124561.

Li, Xiaolu, et al. “Lactate Metabolism in Human Health and Disease.” Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, vol. 7, no. 1, Sept. 2022, p. 305. www.nature.com, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-01151-3.

Liu, Changlu, et al. “Lactate Inhibits Lipolysis in Fat Cells through Activation of an Orphan G-Protein-Coupled Receptor, GPR81*.” Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 284, no. 5, Jan. 2009, pp. 2811–22. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M806409200.

Maculewicz, Ewelina, et al. “The Interactions between Monocarboxylate Transporter Genes MCT1, MCT2, and MCT4 and the Kinetics of Blood Lactate Production and Removal after High-Intensity Efforts in Elite Males: A Cross-Sectional Study.” BMC Genomics, vol. 26, Feb. 2025, p. 133. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-025-11307-4.

Maestro, Antonio, et al. “Genetic Profile in Genes Associated with Muscle Injuries and Injury Etiology in Professional Soccer Players.” Frontiers in Genetics, vol. 13, Nov. 2022. Frontiers, https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.1035899.

Marshall, M. W., et al. “Changes in Lactate Dehydrogenase, LDH Isoenzymes, Lactate, and Pyruvate as a Result of Feeding Low Fat Diets to Healthy Men and Women.” Metabolism, vol. 25, no. 2, Feb. 1976, pp. 169–78. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/0026-0495(76)90047-0.

Marzi, Carola, et al. “Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Two Novel Regions at 11p15.5-P13 and 1p31 with Major Impact on Acute-Phase Serum Amyloid A.” PLoS Genetics, vol. 6, no. 11, Nov. 2010, p. e1001213. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001213.

Massidda, Myosotis, et al. “Influence of the MCT1 Rs1049434 on Indirect Muscle Disorders/Injuries in Elite Football Players.” Sports Medicine – Open, vol. 1, Oct. 2015, p. 33. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-015-0033-9.

McKay, T. B., et al. “Quercetin Attenuates Lactate Production and Extracellular Matrix Secretion in Keratoconus.” Scientific Reports, vol. 5, Mar. 2015, p. 9003. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09003.

Norman, Barbara, et al. “Regulation of Skeletal Muscle ATP Catabolism by AMPD1 Genotype during Sprint Exercise in Asymptomatic Subjects.” Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 91, no. 1, July 2001, pp. 258–64. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.2001.91.1.258.

Pani, Sarita, et al. “Phytocompounds Curcumin, Quercetin, Indole‐3‐carbinol, and Resveratrol Modulate Lactate–Pyruvate Level along with Cytotoxic Activity in HeLa Cervical Cancer Cells.” Biotechnology and Applied Biochemistry, Nov. 2020, p. bab.2061. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1002/bab.2061.

Qu, Yaqian, et al. “The Different Effects of Intramuscularly-Injected Lactate on White and Brown Adipose Tissue in Vivo.” Molecular Biology Reports, vol. 49, no. 9, Sept. 2022, pp. 8507–16. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-022-07672-y.

Rannou, Fabrice, et al. “Effects of AMPD1 Common Mutation on the Metabolic-Chronotropic Relationship: Insights from Patients with Myoadenylate Deaminase Deficiency.” PLOS ONE, vol. 12, no. 11, Nov. 2017, p. e0187266. PLoS Journals, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187266.

Shen, Chenlin, et al. “Intestinal Absorption Mechanisms of MTBH, a Novel Hesperetin Derivative, in Caco-2 Cells, and Potential Involvement of Monocarboxylate Transporter 1 and Multidrug Resistance Protein 2.” European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences: Official Journal of the European Federation for Pharmaceutical Sciences, vol. 78, Oct. 2015, pp. 214–24. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2015.07.022.

Shin, So-Youn, et al. “An Atlas of Genetic Influences on Human Blood Metabolites.” Nature Genetics, vol. 46, no. 6, June 2014, pp. 543–50. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2982.

Tassinari, Isadora D’Ávila, et al. “Lactate Protects Microglia and Neurons from Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation/Reoxygenation.” Neurochemical Research, vol. 49, no. 7, July 2024, pp. 1762–81. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-024-04135-7.

Thevenet, Jonathan, et al. “Medium-Chain Fatty Acids Inhibit Mitochondrial Metabolism in Astrocytes Promoting Astrocyte-Neuron Lactate and Ketone Body Shuttle Systems.” FASEB Journal: Official Publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, vol. 30, no. 5, May 2016, pp. 1913–26. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.201500182.

Tin, A., et al. “GCKR and PPP1R3B Identified as Genome-Wide Significant Loci for Plasma Lactate: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study.” Diabetic Medicine : A Journal of the British Diabetic Association, vol. 33, no. 7, July 2016, pp. 968–75. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12971.

Volk, Christopher, et al. “Inhibition of Lactate Export by Quercetin Acidifies Rat Glial Cells in Vitro.” Neuroscience Letters, vol. 223, no. 2, Feb. 1997, pp. 121–24. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3940(97)13420-6.

Zhang, Han, et al. “Lactate Metabolism and Lactylation in Cardiovascular Disease: Novel Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets.” Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, vol. 11, Nov. 2024. Frontiers, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2024.1489438.