Key takeaways:

~ Folic acid is a synthetic, pre-vitamin form of folate that involves a conversion process to be used in your cells.

~ The DHFR gene is essential in the conversion, and genetic variants in DHFR impact how much folic acid you can convert at one time.

~ Many people have unmetabolized (unconverted) folic acid in their bloodstream, with the effects of this being unknown.

Converting Folic Acid into Methylfolate: DHFR Enzyme is Key

Folate (vitamin B9) is essential for DNA synthesis, cell growth, neurotransmitter synthesis, and red blood cell formation. Supplemental folate can come in the form of folic acid or methylfolate, the active form.

Genetic variants in the DHFR gene can impact your ability to convert folic acid to the active form.

Let’s take a look at how folic acid is used by the body, how your genes interact with folic acid, and how to determine which is the right form for you.

How is folic acid different from natural folate from foods?

Folic acid, a synthetic pre-vitamin form of folate (vitamin B9), remains both temperature and pH-stable, allowing for easy addition to processed foods and multivitamins. The chemical name for folic acid is pteroylmonoglutamic acid or PteGlu.

Natural folates from foods differ a bit from synthetic folic acid. Because natural folates contain more than one glutamic acid, they are called pteroylpolyglutamic acid. They are less heat-stable, and cooking or processing can decrease the amount of natural folate in foods.[ref]

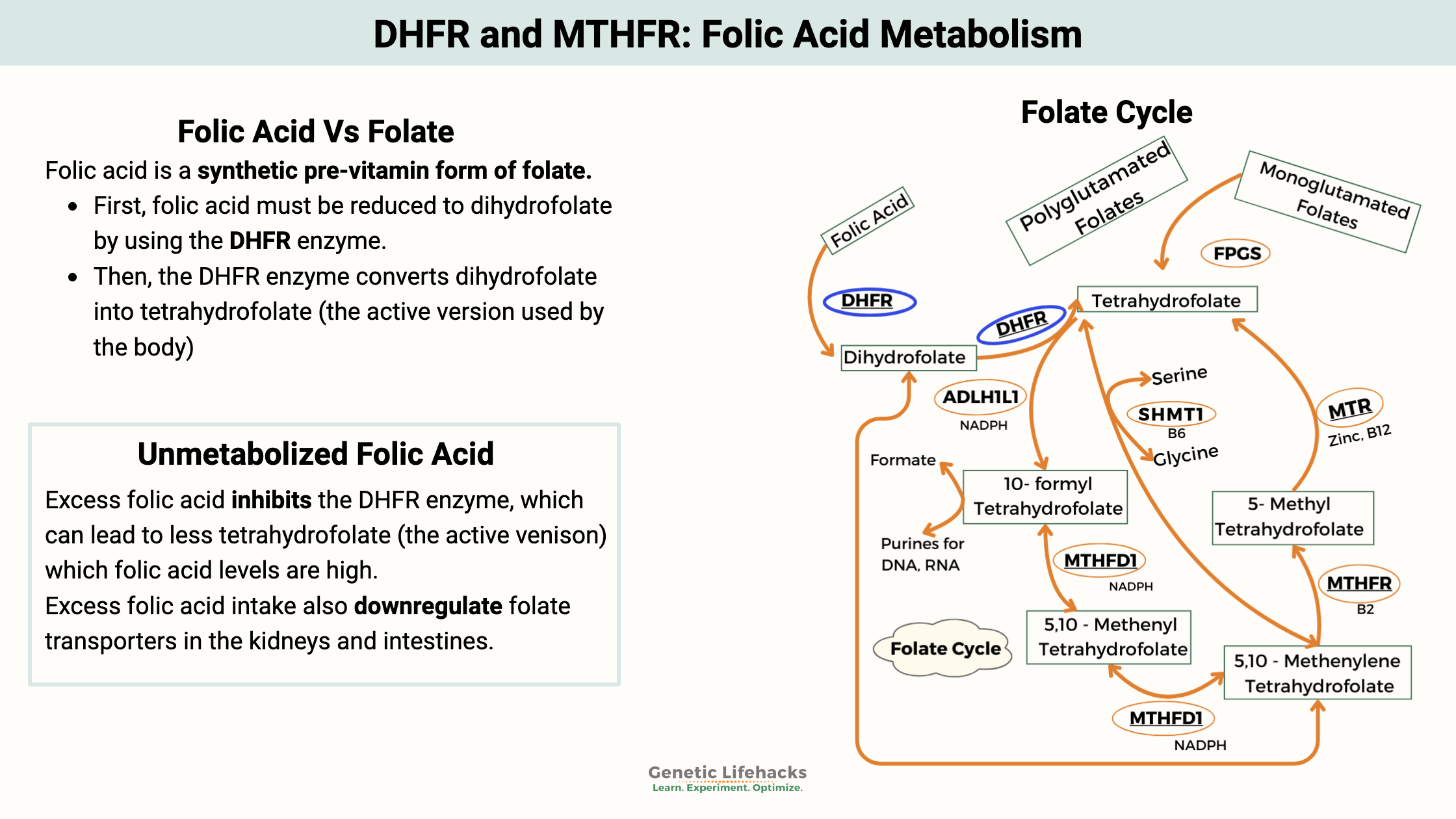

The body converts folates (folic acid and natural folates from plants) into tetrahydrofolate. This conversion process is a little different for natural folate vs. folic acid.

DHFR enzyme in folic acid conversion:

The dihydrofolate reductase enzyme is encoded by the DHFR gene.

- First, folic acid must be reduced to dihydrofolate by using the DHFR enzyme.

- Secondly, the DHFR enzyme converts dihydrofolate into tetrahydrofolate (the active version used by the body).[ref]

Note: The DHFR enzyme is active in two different steps of the conversion process.

MTHFR interaction:

Tetrahydrofolate, along with the MTHFR enzyme, is required in a critical step within the methylation pathway. The methylation pathway is responsible for creating the methyl groups needed in DNA synthesis, detoxification reactions, the creation of certain neurotransmitters, and more.

Forms of folate:

| Form | What it is | Where it’s found | Steps before use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural folate | Reduced folate forms with multiple glutamate residues (pteroylpolyglutamates) | Leafy greens, legumes, liver, other whole foods | Converted to tetrahydrofolate inside cells via folate enzymes |

| Folic acid | Synthetic, oxidized pre‑vitamin (pteroylmonoglutamic acid) used for fortification and many supplements | Fortified flours and grains, many multivitamins and enriched foods | Must be reduced by DHFR to dihydrofolate, then again by DHFR to tetrahydrofolate |

| Methylfolate (L‑5‑MTHF) | Active, methylated folate used directly in methylation cycle | Targeted supplements, some specialized prenatals | Bypasses DHFR and MTHFR steps; higher bioavailability than folic acid in studies |

| Folinic acid (5‑formyl‑THF) | Reduced folate that can be converted to other active forms | Some supplements, medical use with methotrexate | Converted to other tetrahydrofolate forms; Useful when folic acid or MTHFR are problematic |

DFE stands for dietary folate equivalent. For folic acid and methylfolate, the conversion is 0.6 mg folic acid/methylfolate = 1 mg folate from food. It is thought that absorption of folic acid is greater than that of folate from foods. [ref]

Example:

400 mcg folic acid = 680 mcg DFE (folate from food)

What happens to folic acid that isn’t used by the body?

Folic acid is often described as a non-toxic, water-soluble vitamin. This may lead to the assumption that extra folic acid won’t hurt you. However, this may not be correct, with recent research showing that unmetabolized folic acid is associated with several conditions.

Feedback loops: Inhibiting DHFR with excess folic acid

Excess folic acid circulates in the bloodstream as unmetabolized folic acid. This unused folic acid may inhibit the DHFR enzyme from converting dihydrofolate into tetrahydrofolate when the body needs it. Both reactions use the DHFR enzyme, but most of the time, the enzyme is preferentially used for creating the active form (tetrahydrofolate) when needed.

Studies indicate that too much unmetabolized folic acid inhibits DHFR from completing that second reaction. This could leave cells lacking in tetrahydrofolate, even though high levels of folic acid are in circulation.[ref]

There are also concerns that excess folic acid intake could downregulate folate transporters in the kidneys and intestines.[ref]

How much folic acid does it take to get unmetabolized folic acid in the bloodstream?

Studies show varying results, but the range seems to be an excess of 200 to 400 μg/day for most people.

- An excess of 400 μg over the course of the day causes unmetabolized folic acid in the bloodstream for the average adult.[ref]

- Repeated exposures close together of ~200 μg doses show up in the bloodstream.[ref]

- Everyone is unique; there is a large variation in people’s capacity for metabolizing folic acid.[ref]

Most people in the US have unmetabolized folic acid. A study of over 2,700 US children, adolescents, and adults found unmetabolized folic acid in almost all blood samples.[ref]

How much folic acid are people eating?

In the US, flour is fortified at 140 mcg/100g. Here are some examples from commonly eaten foods[ref]:

- A cup and a half of Cheerios provides 40 mcg.[website]

- Two slices of bread for a sandwich give you 70 mcg.

- A bagel contains 119 mcg of folic acid.

- 1 cup of macaroni gives you 179 mcg.

- 1 cup of enriched white rice gives you about 200 mcg, 50% of your daily value for folic acid.

This is just folic acid — keep in mind that foods may contain natural folate as well.

Does folic acid cause cancer?

Folate is needed for cells to reproduce and grow, and cancer cells can use a lot of folate.

Fighting cancer by blocking DHFR:

One commonly used cancer-fighting drug is methotrexate, which blocks the action of an enzyme (DHFR) that is part of the folate pathway. This essentially inhibits the synthesis of DNA, RNA, and more in cancer cells — and healthy cells.

Correlations:

The mandating of folic acid fortification in 1998 correlates with an increase in the number of colon cancer cases in the US. The sharp increase in colon cancers from 1998-2002 came after a long period when colon cancer rates had been declining.[article][ref]

- Recent studies show that folic acid in higher amounts, such as 1mg/day, has links to breast cancer, prostate cancer, and colon cancer.[ref]

- High amounts of unmetabolized folic acid are also associated with decreased natural killer cells (a cytokine that is part of the body’s defense against cancer).[ref]

- People with a higher daily intake of folate (dietary folate, along with some fortified foods with folic acid) have an increased risk of skin cancers.[ref]

Folic acid may be a double-edged sword when it comes to cancer: preventing DNA damage but fueling growth. Here are a few of the studies on cancer and folic acid:

- A study of 848 women with breast cancer and a control group of 28,345 women without cancer found that premenopausal women with higher plasma folate levels were at a higher risk of breast cancer. Researchers noted the results were ‘unexpected’.[ref]

- Women with higher plasma folate levels (top third) were at double the odds of ERβ- breast cancer.[ref]

- A randomized placebo-controlled trial for colorectal adenomas found folic acid supplementation (1 mg/day) more than doubled the risk of prostate cancer.[ref]

- Animal studies show that folic acid affects tumor growth. A study in animals with mammary tumors showed that a diet containing higher amounts of folic acid (2.5 to 5 times the recommended amount) increased tumor size.[ref] Another animal model of breast cancer also found that a high folic acid diet increased tumor volume significantly.[ref]

Positive effects of folate:

Folate in the right amounts has been repeatedly shown to reduce the risk of getting cancer. The key here seems to be that adding folic acid when there is cancer already present will increase the growth of cancer.

Does folic acid cause autism?

This is another controversial topic, and again, with no clear answer or solid evidence. A meta-analysis that combined data from multiple studies showed the overall effect of supplementing with folic acid while pregnant reduces the risk of autism.[ref] Other studies, though, raise some serious questions about folic acid being detrimental on an individual level. A study of 1,391 mothers in Boston found that really high maternal folate and/or B12 levels significantly increased the risk of autism in their children. Overall, though, women using multivitamins were at a lower risk. The researchers did factor in MTHFR genetic variants and found they were not a risk factor.[ref] Animal studies show that high folic acid during pregnancy leads the offspring to have disturbed choline/methyl metabolism, memory impairment, and embryonic growth delays.[ref]

History of how folic acid fortification was mandated in the US:

Widespread folic acid fortification began in the US in 1996 and then became mandatory in 1998. It is currently added to all “enriched bread, flour, cornmeal, rice, pasta, and other grain products”.[ref] This mandate was made to reduce the risk of neural tube defects, which occurred at the rate of 2,500 babies with NTDs/year in the US in 1992.[ref]

The history of the FDA’s decision to mandate fortification with folic acid is interesting to read. A Hungarian study showed a reduced risk of NTDs with 800 mcg/folic acid, and a study called the Werler study in Boston, Toronto, and Philadelphia found 400 mcg/day of folic acid likely reduced NTDs. They also haad studies showing that 250 mcg of dietary folate was protective. Thus, they recommended that everyone of childbearing age have 400 mcg/day with levels not exceeding 1 mg/day (1,000 mcg/day). [ref]

DHFR and BH4 (tetrahydrobiopterin):

The DHFR enzyme is also used in another cellular reaction – regenerating BH4 from BH2. BH4 (tetrahydrobiopterin) is an antioxidant and cofactor in the production of nitric oxide, dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and the metabolism of phenylalanine.

Recycling pathway:

BH4 can be regenerated from BH2, which is the oxidized form. The salvage and recycling pathways involve two enzymes: DHFR and DHPR (also known as QDPR). [ref] The salvage pathway is important not only to produce more BH4, but also to reduce BH2 levels. Excess BH2 or an altered BH2:Bh4 ratio can lead to the generation of superoxide. Superoxide is a powerful oxidant that can cause oxidative stress in a cell.

The salvage pathway uses the DHFR enzyme to reduce (redox reaction) BH2 back to BH4. [ref] Research suggests that one way that folic acid benefits heart health and nitric oxide production is by inducing DHFR enzyme production, thereby increasing the recycling of BH4.[ref][ref] However, some studies indicate that in people with DHFR variants (see the genotype report), excess folic acid intake may feed back and inhibit DHFR capabilities to increase BH4.[ref]

Related Article: BH4: Tetrahydrobiopterin Synthesis, Recycling, and Genetics

Folic Acid Genotype Report:

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks: Folic acid, folate, or methylfolate

Here are some common-sense ways to apply the research on the DHFR SNPs.

Figure out how much folic acid you get in a day:

I think caution is warranted for higher doses of folic acid, especially in older people or anyone at a higher risk for cancer.

Related article: Are you getting too much folate?

The question remains whether a “higher dose” is 200 mcg or 400 mcg, since the studies referenced above showed different answers for the point at which unmetabolized folic acid is found. Genetics likely plays a role, and for anyone with a DHFR variant, the 200 mcg/day levels is likely the sweet spot if you eat a diet that also contains sufficient folate.

Be sure to check the ingredient labels on multivitamins, prepackaged shakes, vitamin drinks, etc., to see how much you are getting.

The European Union and the FDA set the upper limit for folic acid and/or methylfolate at 1,000 mcg (1mg)/day.[ref]

What about prenatal vitamins?

The research is pretty detailed that women trying to conceive need plenty of folate during the first trimester, but this doesn’t mean that folic acid is your only option. There are many options now for prenatal vitamins with methylfolate rather than folic acid. Folinic acid is another option.

A 2025 study showed that methylfolate improves pregnancy outcomes and also decreases the level of unmetabolized folic acid.[ref]

What about MTHFR? Should I limit folic acid due to having MTHFR SNPs?

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

References: