Key takeaways:

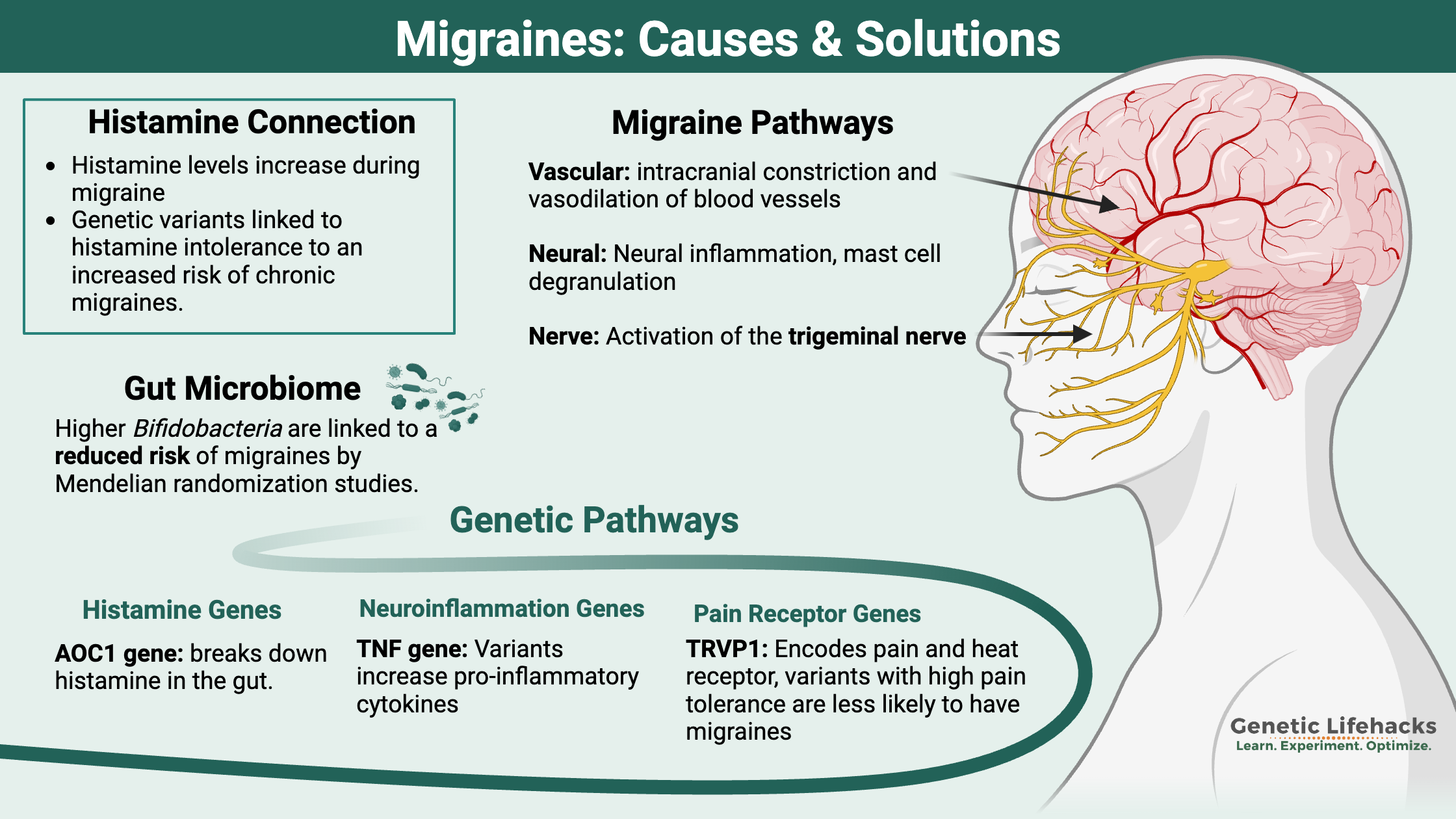

- When looking at the root causes of migraines, three pathways seem to be involved: vascular, neural, and pain/nerve pathways.

- Researchers estimate that migraines are ~50% due to hereditary factors (such as genetic variants), which combine with environmental factors (hormones, high histamine foods) to cause migraines

- Genetic variants in these different pathways may help you pinpoint your triggers of migraines.

- There are natural options backed by research that may help with preventing migraines – or at least decreasing the number of migraine days. Genetics may give you the starting point to figure out which prevention strategies are more likely to work for you.

Members will see their genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

Background science: What happens in the brain with a migraine?

Migraines impact over a billion people globally, and women are three times as likely as men to suffer from them.[ref]

Migraine symptoms generally include:

- Headache, usually lasting 4 to 72 hours

- Sensitivity to light, sounds, and smells

- Nausea or vomiting

- Sensory disturbances, aura (sometimes)

For many, migraines are more than a headache — and, usually, the pain isn’t even the worst part. Instead, it’s the altered ability to think, irritability, nausea, slowed reflexes, and body temperature fluctuations.

There are different types of migraines:

- migraines with aura (about 1/3 of migraineurs get auras)

- migraines without aura

- hemiplegic migraines (rare numbness/tingling on one side of the body)

Some people get prodromal symptoms, which may appear up to a day or two before the migraine. Irritability, fatigue, food cravings, stiff neck, sensitivity to sounds, and yawning are some of the warning signs. On a PET scan, these symptoms accompany an increased blood flow to the hypothalamus.[ref]

Chronic migraines:

Around 2% of the population is affected by chronic migraines, which are usually defined by having 8+ migraine days each month.[ref]

What is going on in your brain when you have a migraine?

Research shows that migraines are complex, with dysfunction occurring in multiple systems rather than a simple, single cause.

Serotonin? In the 1960s, researchers found that people with migraines had higher levels of a serotonin metabolite, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), in their urine. This has prompted a lot of research over the past five decades into the relationship between the serotonergic system and migraines.

Neurovascular changes: More recently, researchers have also investigated how CGRP (calcitonin gene-related peptide), neuroinflammation, and altered ion levels impact migraines.[ref]

Brain electrical storm: Migraines are often described as an excitatory state in the brain – also known as a state of hypersynchrony. Other researchers describe migraines as the brain overresponding to stimuli.[ref]

Migraine research breaks down into three paths:

- vascular causes (intracranial constriction and vasodilation of blood vessels)

- neural events (hyperexcitability and cortical spreading depression)

- nociceptive causes (pain pathways, activation of the trigeminal nerve, neuropeptides)

Vasodilation and migraines:

Part of what happens in your brain during a migraine suggests vasodilation, which is the widening of blood vessels in your brain that decreases blood pressure. The vasodilation reaction follows an initial period of vasoconstriction. The changes in pressure and expansion in the blood vessels are thought to trigger pain receptors in the nerves surrounding the vessels.[ref]

These vascular changes may be due (at least in part) to serotonin signaling. Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HTP) is a neurotransmitter that causes the signal to flow from one neuron to the next. It is found in abundance in both the digestive system and the brain. Brain morphology, the way the neurons in the brain are shaped and formed, is also affected by serotonin.

Serotonin is a signaling molecule, and it needs a receptor to bind to and cause an action. Different types of serotonin receptors are found throughout the brain and intestinal tract, causing diverse effects of serotonin.[ref]

One big link between migraines and serotonin is that triptans, the most commonly used migraine prescription medication, work by amplifying the serotonin signal. Triptans act on the serotonin receptors (5-HT1B) in the blood vessels of the brain, constricting them and inhibiting the release of neuropeptides.[ref]

Genetic studies show a link between migraine susceptibility and a type of genetic variant known as a variable number tandem repeat in a serotonin transporter gene.[ref]

Using PET scans on people who had been migraine-free for at least 48 hours, researchers can study the 5-HT1B (serotonin) receptor in the brain. These scans showed that migraine patients had lower 5-HT1B binding than those without migraines. The results of the study suggest two possibilities:[ref]

- Low numbers of serotonin receptors may either be causal (low serotonin causing migraines)

– or- - Serotonin receptors decrease over time because of repeated exposure to migraines.

In other words, it isn’t determined if low serotonin causes migraines or if migraines cause changes to the expression of serotonin receptors. (Check your serotonin variants in the genotype report below)

Melatonin and migraines:

Researchers also found low melatonin levels in people with chronic migraines when compared to a control population. It is notable, especially because serotonin is needed for the reaction in the pineal gland that produces melatonin.[ref]

tryptophan -> serotonin -> melatonin

One study explains that serotonin levels are low between migraine attacks, but levels increase rapidly at the beginning of a migraine. This initial surge of serotonin causes vasoconstriction and is thought to be part of the aura phase. When serotonin breaks down (which happens pretty quickly), serotonin levels drop, causing vasodilation and headache pain.[ref]

Related article: Serotonin: How your genes affect this neurotransmitter

CGRP in migraines: Neurons + vascular changes

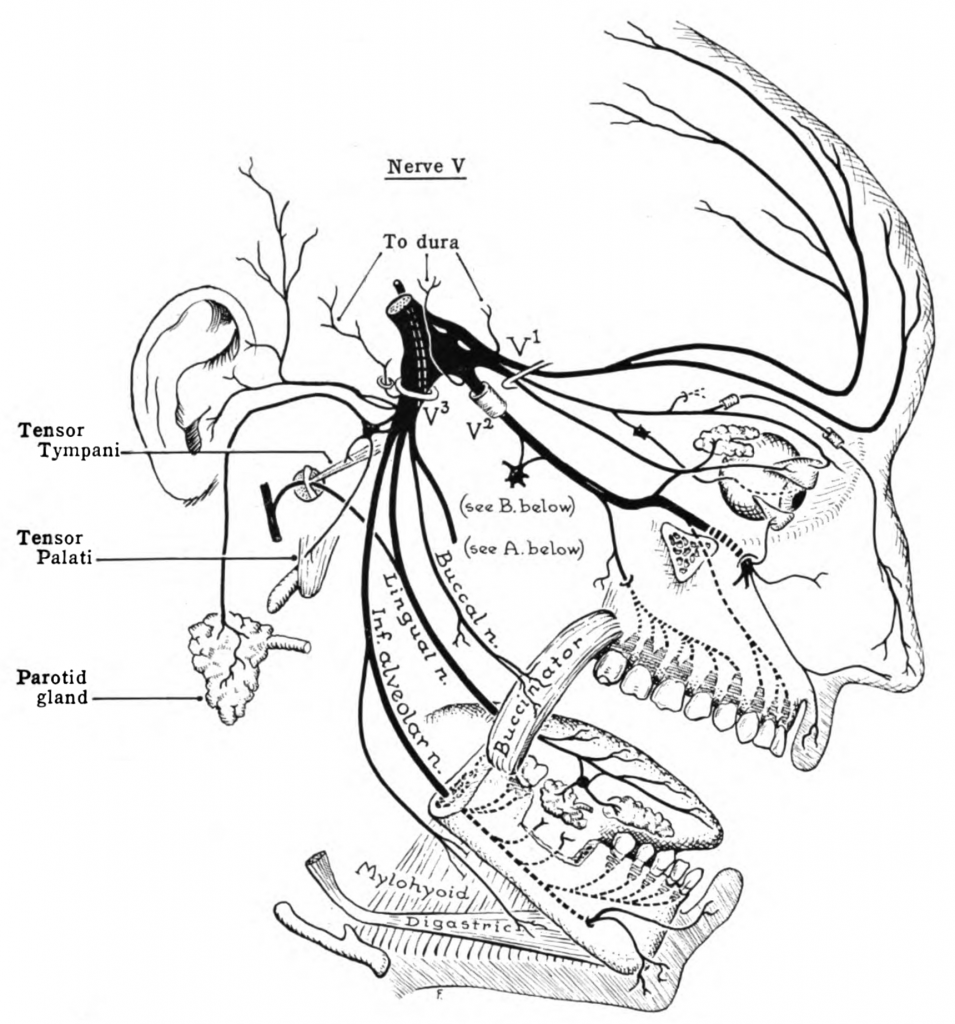

Another key player in migraines is CGRP. CGRP stands for calcitonin gene-related peptide and is released from the trigeminovascular system. The trigeminovascular system includes both the trigeminal nerve neurons and the cerebral blood vessels.

The trigeminal nerve is the largest cranial nerve. It branches from the temple to over the eyebrows, and down to the teeth and jaw. Here’s a graphic showing where the trigeminal nerve is located:

The sensory nerve fibers of the trigeminal nerve can activate the release of neuropeptides, including CGRP, substance P, and neurokinin A.

CGRP is a potent vasodilator, making it important for both migraines and normal blood pressure regulation in the body. It is also thought to influence the pain portion of migraines.[ref][ref]

There are a lot of new migraine drugs being developed that focus on CGRP. However, a CGRP isn’t solely responsible for migraines, and medications that target CGRP only work for a portion of patients.[ref] CGRP can also bind to the amylin 1 receptor in the brain. New research points to this being a possible pathway involved in the way that is involved in causing migraines.[ref]

(Check your CGRP variants in the genotype report below)

Neuroinflammation in migraines:

The release of CGRP activates receptors on several different cell types, including mast cells. Mast cells are part of the body’s immune system and are found in all of our body tissues. They stand ready to release a payload of histamine, serotonin, tryptase, and inflammatory cytokines when activated by a pathogen, allergic reaction, or other signaling molecules (such as CGRP).[ref]

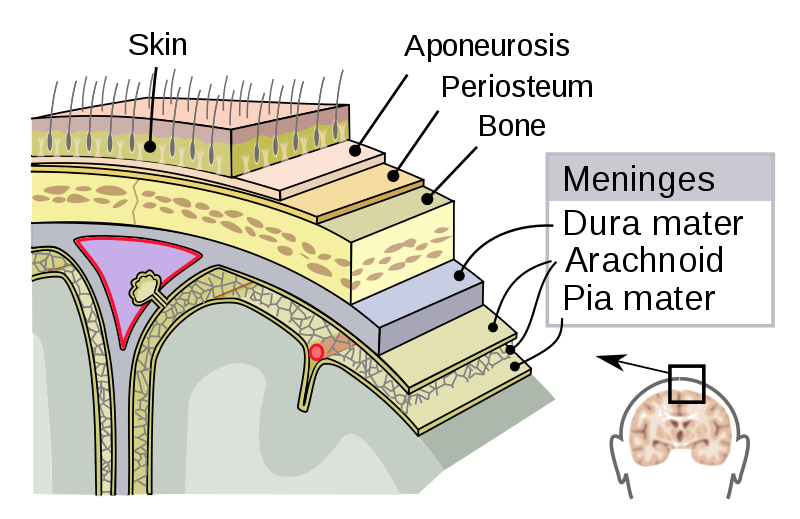

The activated mast cells can degranulate, releasing histamine and pro-inflammatory compounds. This degranulation of mast cells causes a “prolonged state of excitation in meningeal nociceptors”. The meninges line the skull, and nociceptors are pain receptors.[ref][ref]

Here is an image of the meninges, which includes three layers surrounding the brain (dura mater, arachnoid, and pia mater).

The brain itself doesn’t have pain receptors, but there are pain receptors and blood vessels throughout the meninges.

Some researchers theorize that mast cells and neuroinflammation are at the root of migraine pathology. Here are two reasons pointing to mast cell degranulation as a root cause:

- Histamine, released when mast cells degranulate, is elevated during migraine attacks.[ref]

- Tryptase is also released during degranulation and is thought to sensitize pain receptors.[ref]

(Check your histamine variants in the migraine genotype report below)

Other researchers theorize that central sensitization is at the root of migraines. Central sensitization involves enhanced signaling through pain pathways and is caused by overexcited pain receptors and decreased inhibition. This term applies to various pain-related conditions such as peripheral neuropathy, IBS, and migraines.[ref]

Related article: Mast cells: MCAS, genetics, and solutions

Ion levels: Can an electrolyte imbalance cause migraines?

Another observation of researchers is that ion levels are often altered in migraineurs.

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

Histamine Intolerance: Genetic Report, Supplements, and Real Solutions

References:

“Temporalis Trigger Points and Referred Pain Patterns.” Triggerpointselfhelp.Com, 3 Mar. 2019, https://triggerpointselfhelp.com/temporalis-trigger-points-and-referred-pain-patterns/.

Amin, Faisal Mohammad, et al. “The Association between Migraine and Physical Exercise.” The Journal of Headache and Pain, vol. 19, no. 1, Sept. 2018, p. 83. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0902-y.

An, Xing-Kai, et al. “Association of MTHFR C677T Polymorphism with Susceptibility to Migraine in the Chinese Population.” Neuroscience Letters, vol. 549, Aug. 2013, pp. 78–81. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2013.06.028.

Andreeva, Valentina A., et al. “Macronutrient Intake in Relation to Migraine and Non-Migraine Headaches.” Nutrients, vol. 10, no. 9, Sept. 2018, p. 1309. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10091309.

Anttila, Verneri, et al. “Genome-Wide Meta-Analysis Identifies New Susceptibility Loci for Migraine.” Nature Genetics, vol. 45, no. 8, Aug. 2013, pp. 912–17. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2676.

—. “Genome-Wide Meta-Analysis Identifies New Susceptibility Loci for Migraine.” Nature Genetics, vol. 45, no. 8, Aug. 2013, pp. 912–17. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2676.

Baena, Cristina Pellegrino, et al. “The Effectiveness of Aspirin for Migraine Prophylaxis: A Systematic Review.” Sao Paulo Medical Journal = Revista Paulista De Medicina, vol. 135, no. 1, Feb. 2017, pp. 42–49. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-3180.2016.0165050916.

Baj, Tirthraj, and Rohit Seth. “Role of Curcumin in Regulation of TNF-α Mediated Brain Inflammatory Responses.” Recent Patents on Inflammation & Allergy Drug Discovery, vol. 12, no. 1, 2018, pp. 69–77. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.2174/1872213X12666180703163824.

Bayerer, Bettina, et al. “Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms of the Serotonin Transporter Gene in Migraine–an Association Study.” Headache, vol. 50, no. 2, Feb. 2010, pp. 319–22. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01553.x.

Benemei, Silvia, et al. “Triptans and CGRP Blockade – Impact on the Cranial Vasculature.” The Journal of Headache and Pain, vol. 18, no. 1, Oct. 2017, p. 103. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-017-0811-5.

—. “Triptans and CGRP Blockade – Impact on the Cranial Vasculature.” The Journal of Headache and Pain, vol. 18, no. 1, Oct. 2017, p. 103. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-017-0811-5.

—. “Triptans and CGRP Blockade – Impact on the Cranial Vasculature.” The Journal of Headache and Pain, vol. 18, no. 1, Oct. 2017, p. 103. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-017-0811-5.

—. “Triptans and CGRP Blockade – Impact on the Cranial Vasculature.” The Journal of Headache and Pain, vol. 18, no. 1, Oct. 2017, p. 103. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-017-0811-5.

BORAN, H. Evren, and Hayrunnisa BOLAY. “Pathophysiology of Migraine.” Nöro Psikiyatri Arşivi, vol. 50, no. Suppl 1, Aug. 2013, pp. S1–7. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.4274/Npa.y7251.

Buldyrev, Ilya, et al. “Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide Enhances Release of Native Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor from Trigeminal Ganglion Neurons.” Journal of Neurochemistry, vol. 99, no. 5, Dec. 2006, pp. 1338–50. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04161.x.

Cady, Roger, et al. “SumaRT/Nap vs Naproxen Sodium in Treatment and Disease Modification of Migraine: A Pilot Study.” Headache, vol. 54, no. 1, Jan. 2014, pp. 67–79. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12211.

Cameron, Chris, et al. “Triptans in the Acute Treatment of Migraine: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis.” Headache, vol. 55 Suppl 4, Aug. 2015, pp. 221–35. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12601.

Chasman, Daniel I., et al. “Genome-Wide Association Study Reveals Three Susceptibility Loci for Common Migraine in the General Population.” Nature Genetics, vol. 43, no. 7, July 2011, pp. 695–98. www.nature.com, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.856.

—. “Genome-Wide Association Study Reveals Three Susceptibility Loci for Common Migraine in the General Population.” Nature Genetics, vol. 43, no. 7, July 2011, pp. 695–98. www.nature.com, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.856.

Chehl, Navdeep, et al. “Anti-Inflammatory Effects of the Nigella Sativa Seed Extract, Thymoquinone, in Pancreatic Cancer Cells.” HPB : The Official Journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association, vol. 11, no. 5, Aug. 2009, pp. 373–81. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00059.x.

Chiang, Chia-Chun, and Amaal J. Starling. “OnabotulinumtoxinA in the Treatment of Patients with Chronic Migraine: Clinical Evidence and Experience.” Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders, vol. 10, no. 12, Dec. 2017, pp. 397–406. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1177/1756285617731521.

Duan, Chenyang, et al. “Abnormal Neurovascular Coupling Induces Glymphatic Dysfunction in a Mouse Model of Familial Hemiplegic Migraine Type 2.” The Journal of Headache and Pain, vol. 26, no. 1, Nov. 2025, p. 257. Springer Link, https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-025-02194-x.

—. “OnabotulinumtoxinA in the Treatment of Patients with Chronic Migraine: Clinical Evidence and Experience.” Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders, vol. 10, no. 12, Dec. 2017, pp. 397–406. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1177/1756285617731521.

Christ, Pia, et al. “The Circadian Clock Drives Mast Cell Functions in Allergic Reactions.” Frontiers in Immunology, vol. 9, July 2018, p. 1526. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.01526.

Daubert, Elizabeth A., and Barry G. Condron. “Serotonin: A Regulator of Neuronal Morphology and Circuitry.” Trends in Neurosciences, vol. 33, no. 9, Sept. 2010, pp. 424–34. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2010.05.005.

Deen, Marie, et al. “Low 5-HT1B Receptor Binding in the Migraine Brain: A PET Study.” Cephalalgia: An International Journal of Headache, vol. 38, no. 3, Mar. 2018, pp. 519–27. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102417698708.

Demarquay, G., et al. “Olfactory Hypersensitivity in Migraineurs: A H(2)(15)O-PET Study.” Cephalalgia: An International Journal of Headache, vol. 28, no. 10, Oct. 2008, pp. 1069–80. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01672.x.

—. “Olfactory Hypersensitivity in Migraineurs: A H(2)(15)O-PET Study.” Cephalalgia: An International Journal of Headache, vol. 28, no. 10, Oct. 2008, pp. 1069–80. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01672.x.

Di Lorenzo, C., et al. “Migraine Improvement during Short Lasting Ketogenesis: A Proof-of-Concept Study.” European Journal of Neurology, vol. 22, no. 1, Jan. 2015, pp. 170–77. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.12550.

Dodick, David W., et al. “Effect of Fremanezumab Compared With Placebo for Prevention of Episodic Migraine: A Randomized Clinical Trial.” JAMA, vol. 319, no. 19, May 2018, pp. 1999–2008. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.4853.

Drummond, P. D. “Tryptophan Depletion Increases Nausea, Headache and Photophobia in Migraine Sufferers.” Cephalalgia: An International Journal of Headache, vol. 26, no. 10, Oct. 2006, pp. 1225–33. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01212.x.

Durham, Paul L. “Diverse Physiological Roles of Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide in Migraine Pathology: Modulation of Neuronal-Glial-Immune Cells to Promote Peripheral and Central Sensitization.” Current Pain and Headache Reports, vol. 20, no. 8, Aug. 2016, p. 48. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-016-0578-4.

—. “Diverse Physiological Roles of Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide in Migraine Pathology: Modulation of Neuronal-Glial-Immune Cells to Promote Peripheral and Central Sensitization.” Current Pain and Headache Reports, vol. 20, no. 8, Aug. 2016, p. 48. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-016-0578-4.

—. “Diverse Physiological Roles of Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide in Migraine Pathology: Modulation of Neuronal-Glial-Immune Cells to Promote Peripheral and Central Sensitization.” Current Pain and Headache Reports, vol. 20, no. 8, Aug. 2016, p. 48. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-016-0578-4.

Ebrahimi-Monfared, Mohsen, et al. “Use of Melatonin versus Valproic Acid in Prophylaxis of Migraine Patients: A Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial.” Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience, vol. 35, no. 4, 2017, pp. 385–93. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3233/RNN-160704.

Evans, E. Whitney, et al. “Dietary Intake Patterns and Diet Quality in a Nationally Representative Sample of Women with and without Severe Headache or Migraine.” Headache, vol. 55, no. 4, Apr. 2015, pp. 550–61. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12527.

Foods Highest in Tryptophan. https://nutritiondata.self.com/foods-000079000000000000000.html. Accessed 3 Sept. 2021.

García-Martín, Elena, et al. “Diamine Oxidase Rs10156191 and Rs2052129 Variants Are Associated with the Risk for Migraine.” Headache, vol. 55, no. 2, Feb. 2015, pp. 276–86. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12493.

Gasparini, Claudia Francesca, et al. “Genetic and Biochemical Changes of the Serotonergic System in Migraine Pathobiology.” The Journal of Headache and Pain, vol. 18, no. 1, Feb. 2017, p. 20. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-016-0711-0.

—. “Genetic and Biochemical Changes of the Serotonergic System in Migraine Pathobiology.” The Journal of Headache and Pain, vol. 18, no. 1, Feb. 2017, p. 20. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-016-0711-0.

—. “Genetic and Biochemical Changes of the Serotonergic System in Migraine Pathobiology.” The Journal of Headache and Pain, vol. 18, no. 1, Feb. 2017, p. 20. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-016-0711-0.

Goadsby, Peter J., et al. “Pathophysiology of Migraine: A Disorder of Sensory Processing.” Physiological Reviews, vol. 97, no. 2, Apr. 2017, pp. 553–622. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00034.2015.

—. “Pathophysiology of Migraine: A Disorder of Sensory Processing.” Physiological Reviews, vol. 97, no. 2, Apr. 2017, pp. 553–622. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00034.2015.

—. “Pathophysiology of Migraine: A Disorder of Sensory Processing.” Physiological Reviews, vol. 97, no. 2, Apr. 2017, pp. 553–622. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00034.2015.

Gonçalves, Andre Leite, et al. “Randomised Clinical Trial Comparing Melatonin 3 Mg, Amitriptyline 25 Mg and Placebo for Migraine Prevention.” Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, vol. 87, no. 10, Oct. 2016, pp. 1127–32. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2016-313458.

Heatley, R. V., et al. “Increased Plasma Histamine Levels in Migraine Patients.” Clinical Allergy, vol. 12, no. 2, Mar. 1982, pp. 145–49. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.1982.tb01633.x.

John, P. J., et al. “Effectiveness of Yoga Therapy in the Treatment of Migraine without Aura: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Headache, vol. 47, no. 5, May 2007, pp. 654–61. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00789.x.

Karimi, Narges, et al. “The Efficacy of Magnesium Oxide and Sodium Valproate in Prevention of Migraine Headache: A Randomized, Controlled, Double-Blind, Crossover Study.” Acta Neurologica Belgica, vol. 121, no. 1, Feb. 2021, pp. 167–73. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13760-019-01101-x.

Kayama, Yohei, et al. “Functional Interactions between Transient Receptor Potential M8 and Transient Receptor Potential V1 in the Trigeminal System: Relevance to Migraine Pathophysiology.” Cephalalgia, vol. 38, no. 5, Apr. 2018, pp. 833–45. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102417712719.

Key, Felix M., et al. “Human Local Adaptation of the TRPM8 Cold Receptor along a Latitudinal Cline.” PLoS Genetics, vol. 14, no. 5, May 2018, p. e1007298. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1007298.

Kilinc, E., et al. “Effects of Nigella Sativa Seeds and Certain Species of Fungi Extracts on Number and Activation of Dural Mast Cells in Rats.” Physiology International, vol. 104, no. 1, Mar. 2017, pp. 15–24. akjournals.com, https://doi.org/10.1556/2060.104.2017.1.8.

Koyuncu Irmak, Duygu, et al. “Shared Fate of Meningeal Mast Cells and Sensory Neurons in Migraine.” Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, vol. 13, Apr. 2019, p. 136. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2019.00136.

Krueger, J. M., et al. “Sleep. A Physiologic Role for IL-1 Beta and TNF-Alpha.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 856, Sept. 1998, pp. 148–59. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08323.x.

Latremoliere, Alban, and Clifford J. Woolf. “Central Sensitization: A Generator of Pain Hypersensitivity by Central Neural Plasticity.” The Journal of Pain : Official Journal of the American Pain Society, vol. 10, no. 9, Sept. 2009, pp. 895–926. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2009.06.012.

Lin, Qi-Fang, et al. “Association of Genetic Loci for Migraine Susceptibility in the She People of China.” The Journal of Headache and Pain, vol. 16, 2015, p. 553. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-015-0553-1.

Liu, Hua, et al. “Association of 5-HTT Gene Polymorphisms with Migraine: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of the Neurological Sciences, vol. 305, no. 1–2, June 2011, pp. 57–66. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2011.03.016.

Liu, Ruozhuo, et al. “MTHFR C677T Polymorphism and Migraine Risk: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of the Neurological Sciences, vol. 336, no. 1–2, Jan. 2014, pp. 68–73. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2013.10.008.

—. “MTHFR C677T Polymorphism and Migraine Risk: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of the Neurological Sciences, vol. 336, no. 1–2, Jan. 2014, pp. 68–73. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2013.10.008.

Magalhães, Elza, et al. “Botulinum Toxin Type A versus Amitriptyline for the Treatment of Chronic Daily Migraine.” Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery, vol. 112, no. 6, July 2010, pp. 463–66. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.02.004.

Masruha, Marcelo R., et al. “Urinary 6-Sulphatoxymelatonin Levels Are Depressed in Chronic Migraine and Several Comorbidities.” Headache, vol. 50, no. 3, Mar. 2010, pp. 413–19. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01547.x.

McKemy, David D. “TRPM8: The Cold and Menthol Receptor.” TRP Ion Channel Function in Sensory Transduction and Cellular Signaling, edited by Wolfgang B. Liedtke and Stefan Heller, CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, 2007. PubMed, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK5238/.

—. “TRPM8: The Cold and Menthol Receptor.” TRP Ion Channel Function in Sensory Transduction and Cellular Signaling, edited by Wolfgang B. Liedtke and Stefan Heller, CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, 2007. PubMed, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK5238/.

Meyer, Melissa M., et al. “Cerebral Sodium (23Na) Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients with Migraine – a Case-Control Study.” European Radiology, vol. 29, no. 12, Dec. 2019, pp. 7055–62. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-019-06299-1.

Meza-Velázquez, R., et al. “Association of Diamine Oxidase and Histamine N-Methyltransferase Polymorphisms with Presence of Migraine in a Group of Mexican Mothers of Children with Allergies.” Neurología (English Edition), vol. 32, no. 8, Oct. 2017, pp. 500–07. www.elsevier.es, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nrleng.2016.02.012.

“Migraine Aura.” Mayo Clinic, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/migraine-with-aura/multimedia/migraine-aura/vid-20084707. Accessed 3 Sept. 2021.

“Migraine Intensity, Frequency Linked to High Cholesterol.” National Headache Foundation, 21 Oct. 2015, https://headaches.org/2015/10/21/migraine-intensity-frequency-linked-to-high-cholesterol/.

Mulder, Elles J., et al. “Genetic and Environmental Influences on Migraine: A Twin Study Across Six Countries.” Twin Research and Human Genetics, vol. 6, no. 5, Oct. 2003, pp. 422–31. Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1375/twin.6.5.422.

Parohan, Mohammad, et al. “The Synergistic Effects of Nano-Curcumin and Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation in Migraine Prophylaxis: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Trial.” Nutritional Neuroscience, vol. 24, no. 4, Apr. 2021, pp. 317–26. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415X.2019.1627770.

Peatfield, R. C. “Relationships between Food, Wine, and Beer-Precipitated Migrainous Headaches.” Headache, vol. 35, no. 6, June 1995, pp. 355–57. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.1995.hed3506355.x.

—. “Relationships between Food, Wine, and Beer-Precipitated Migrainous Headaches.” Headache, vol. 35, no. 6, June 1995, pp. 355–57. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.1995.hed3506355.x.

Pogoda, Janice M., et al. “Severe Headache or Migraine History Is Inversely Correlated With Dietary Sodium Intake: NHANES 1999-2004.” Headache, vol. 56, no. 4, Apr. 2016, pp. 688–98. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12792.

Ran, Caroline, et al. “Implications for the Migraine SNP Rs1835740 in a Swedish Cluster Headache Population.” The Journal of Headache and Pain, vol. 19, no. 1, Nov. 2018, p. 100. BioMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0937-0.

Rodriguez-Acevedo, Astrid J., et al. “Genetic Association and Gene Expression Studies Suggest That Genetic Variants in the SYNE1 and TNF Genes Are Related to Menstrual Migraine.” The Journal of Headache and Pain, vol. 15, Oct. 2014, p. 62. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1186/1129-2377-15-62.

Savi, LT, et al. “Prophylaxis of Migraine with Aura: A Place for Acetylsalicylic Acid.” The Journal of Headache and Pain, vol. 14, no. 1, Feb. 2013, p. P195. Springer Link, https://doi.org/10.1186/1129-2377-14-S1-P195.

Sazci, Ali, et al. “Nicotinamide-N-Methyltransferase Gene Rs694539 Variant and Migraine Risk.” The Journal of Headache and Pain, vol. 17, no. 1, Oct. 2016, p. 93. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-016-0688-8.

Schoenen, J., et al. “Effectiveness of High-Dose Riboflavin in Migraine Prophylaxis. A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Neurology, vol. 50, no. 2, Feb. 1998, pp. 466–70. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.50.2.466.

Schürks, Markus, et al. “A Candidate Gene Association Study of 77 Polymorphisms in Migraine.” The Journal of Pain, vol. 10, no. 7, July 2009, pp. 759–66. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2009.01.326.

Silva-Néto, R. P., et al. “Odorant Substances That Trigger Headaches in Migraine Patients.” Cephalalgia: An International Journal of Headache, vol. 34, no. 1, Jan. 2014, pp. 14–21. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102413495969.

Sintas, Cèlia, et al. “Replication Study of Previous Migraine Genome-Wide Association Study Findings in a Spanish Sample of Migraine with Aura.” Cephalalgia: An International Journal of Headache, vol. 35, no. 9, Aug. 2015, pp. 776–82. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102414557841.

—. “Replication Study of Previous Migraine Genome-Wide Association Study Findings in a Spanish Sample of Migraine with Aura.” Cephalalgia: An International Journal of Headache, vol. 35, no. 9, Aug. 2015, pp. 776–82. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102414557841.

Stuart, Shani, et al. “The Role of the MTHFR Gene in Migraine.” Headache, vol. 52, no. 3, Mar. 2012, pp. 515–20. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02106.x.

Talebi, Mahnaz, et al. “Relation between Serum Magnesium Level and Migraine Attacks.” Neurosciences (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia), vol. 16, no. 4, Oct. 2011, pp. 320–23.

Terrazzino, Salvatore, et al. “Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Val66Met Gene Polymorphism Impacts on Migraine Susceptibility: A Meta-Analysis of Case–Control Studies.” Frontiers in Neurology, vol. 8, May 2017, p. 159. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2017.00159.

“Treximet Prices, Coupons & Savings Tips.” GoodRx, https://www.goodrx.com/treximet. Accessed 3 Sept. 2021.

van Oosterhout, Wpj, et al. “Chronotypes and Circadian Timing in Migraine.” Cephalalgia: An International Journal of Headache, vol. 38, no. 4, Apr. 2018, pp. 617–25. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102417698953.

von Luckner, Alexander, and Franz Riederer. “Magnesium in Migraine Prophylaxis-Is There an Evidence-Based Rationale? A Systematic Review.” Headache, vol. 58, no. 2, Feb. 2018, pp. 199–209. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13217.

Wells, Rebecca Erwin, et al. “Meditation for Migraines: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial.” Headache, vol. 54, no. 9, Oct. 2014, pp. 1484–95. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12420.

Yılmaz, Ibrahim Arda, et al. “Cytokine Polymorphism in Patients with Migraine: Some Suggestive Clues of Migraine and Inflammation.” Pain Medicine, vol. 11, no. 4, Apr. 2010, pp. 492–97. Silverchair, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00791.x.

—. “Cytokine Polymorphism in Patients with Migraine: Some Suggestive Clues of Migraine and Inflammation.” Pain Medicine, vol. 11, no. 4, Apr. 2010, pp. 492–97. Silverchair, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00791.x.

Zhang, X. C., and D. Levy. “Modulation of Meningeal Nociceptors Mechanosensitivity by Peripheral Proteinase-Activated Receptor-2: The Role of Mast Cells.” Cephalalgia: An International Journal of Headache, vol. 28, no. 3, Mar. 2008, pp. 276–84. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01523.x.

Zhang, Xichun, et al. “Activation of Meningeal Nociceptors by Cortical Spreading Depression: Implications for Migraine with Aura.” The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, vol. 30, no. 26, June 2010, pp. 8807–14. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0511-10.2010.