Key takeaways:

~This article explains the differences in psychopaths’ brains and the multiple genetic variants linked to psychopathy.

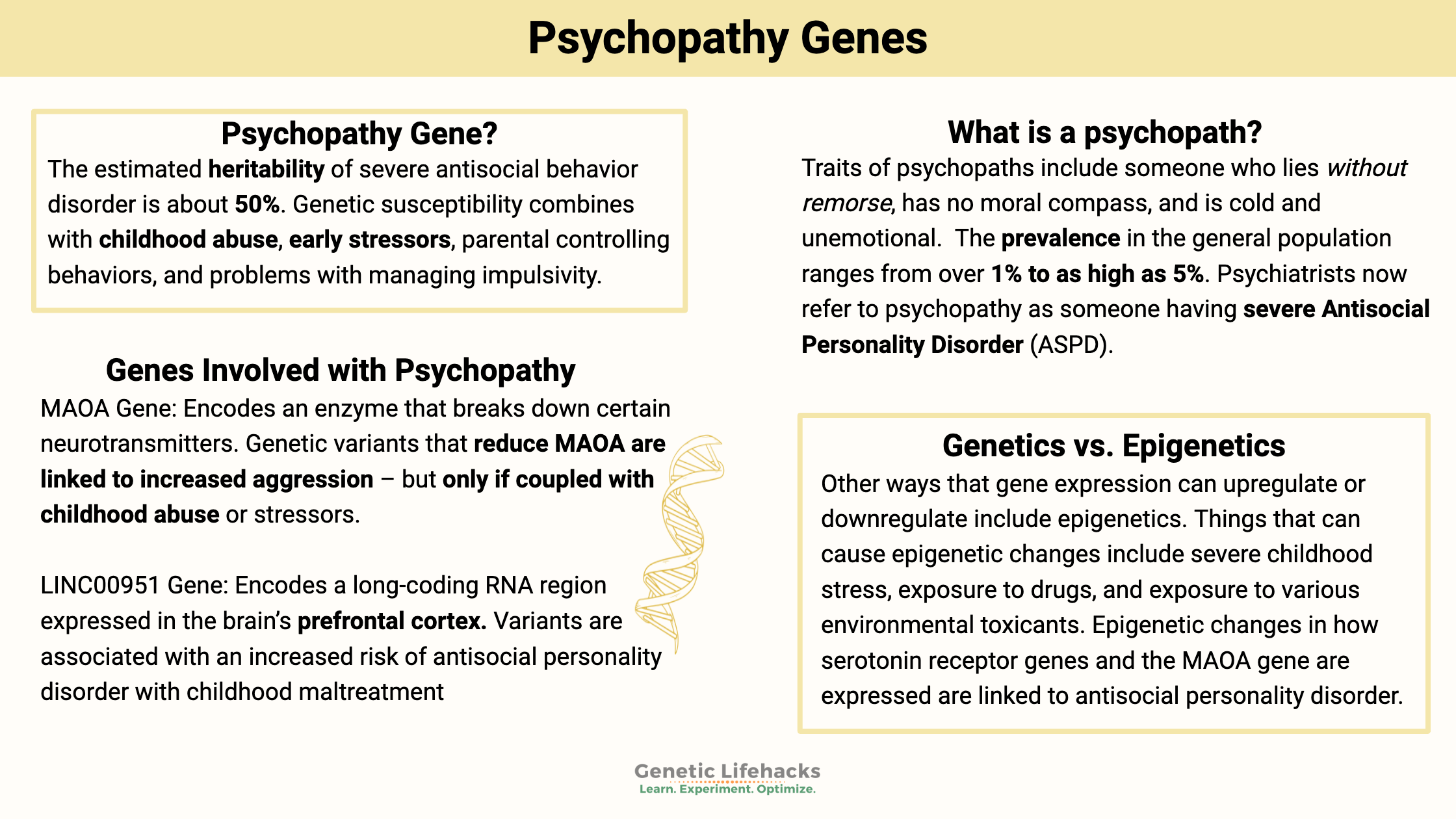

~ The estimated heritability of severe antisocial behavior disorder is about 50%.

~ Genetic susceptibility combines with childhood abuse, early stressors, parental controlling behaviors, and problems with managing impulsivity.

Is there a psychopath gene?

Can you be born a psychopath? The Encyclopedia Britannica explains that “…psychopaths are born, and sociopaths are made.”[ref] Does this mean that if you are born with certain genes, you are destined to be a psychopath?

Pithy sayings, such as ‘psychopaths are born, sociopaths are made’ do hold a kernel of truth… However, they miss the mark in a lot of ways.

Psychopaths are born. Sociopaths are made.

First, there is no single gene variant that causes psychopathy. Instead, a number of common genetic variants are linked to psychopathy and antisocial traits. We all have some ‘psychopath genes’.

Let’s dive into the topic and find out what makes a psychopath tick…

What is a psychopath?

We all have a mental picture of a psychopath – someone who lies without remorse, has no moral compass, and is cold and unemotional. They may be glib, smooth talkers who can lie their way out of a situation. Or they may just come across as emotionless and uncaring.

Depending on how researchers define a psychopath, the prevalence in the general population ranges from over 1% to as high as 5%.[ref]

Psychiatrists now refer to what we traditionally consider a psychopath as someone having severe Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD).

The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for Antisocial Personality Disorder:

“1. A pervasive pattern of disregard for and violation of the rights of others, since age 15 years, as indicated by three (or more) of the following:

-

- Failure to conform to social norms concerning lawful behaviors, such as performing acts that are grounds for arrest.

- Deceitfulness, repeated lying, use of aliases, or conning others for pleasure or personal profit.

- Impulsivity or failure to plan.

- Irritability and aggressiveness, often with physical fights or assaults.

- Reckless disregard for the safety of self or others.

- Consistent irresponsibility, failure to sustain consistent work behavior or honor monetary obligations.

- Lack of remorse, being indifferent to or rationalizing having hurt, mistreated, or stolen from another person.

2. The individual is at least 18 years old.

3. Evidence of conduct disorder typically with onset before age 15 years.

4. The occurrence of antisocial behavior is not exclusively during schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.”[ref]

One study describes antisocial personality disorder as:[ref]

“Antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) is a severe personality disorder characterized by a pervasive pattern of disregarding or violating others’ rights, often without showing interest in the feelings of others “

Is psychopathy really genetic?

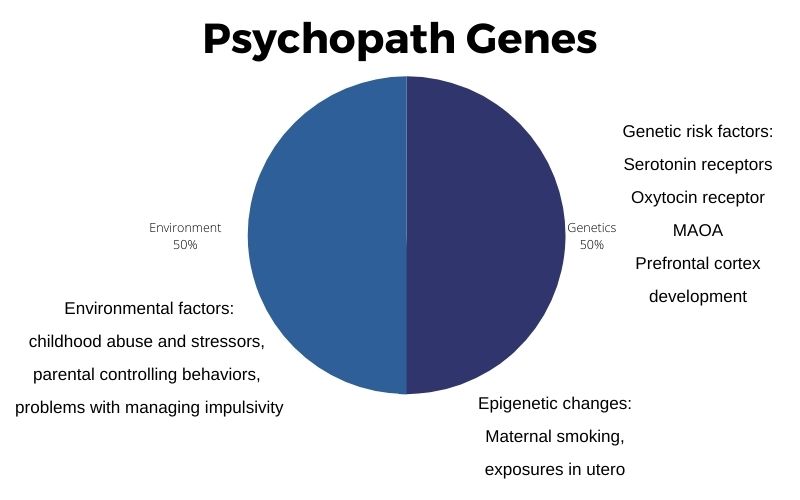

The estimated heritability of severe antisocial behavior disorder is about 50%.[ref]

While psychopathy has a genetic component, your genes don’t predestine you to become a psychopath.

Psychopathy is about half genetic and half other factors.

To clarify: Most of what researchers call ‘heritability’ is the genetic variants or mutations you inherit. However, heritability also includes epigenetics and in utero changes due to exposures before birth.

If heritability is half of psychopathy, what is the rest?

Childhood abuse, early stressors, parental controlling behaviors, and problems with managing impulsivity are intertwined with genetics. Researchers find that all of these can increase the risk in a susceptible individual.[ref]

Environmental factors, such as exposure to cigarette smoke toxins in utero or heavy metal exposure, may also combine with genetic susceptibility.[ref]

Are psychopaths’ brains different?

Intriguingly, studies of psychopathic brains show physical and physiological differences. And these differences may start during brain development.

Starting young:

Researchers have looked at heritability in twin pairs in school-aged children. They found that the traits of being callous and unemotional combined with antisocial behavior are highly heritable. Unsurprisingly, children who were considered callous and unemotional also were much more likely to have conduct problems in school settings.[ref]

Other researchers examined information on study participants in a twins study that had followed the sibling pairs for a couple of decades (birth through young adulthood). They found that showing an early disregard for others in toddlerhood was statistically predictive of specific psychopathy traits in young adults.[ref]

Changes in the brain:

MRI studies on callous, unemotional, antisocial children showed a decrease in white matter and an increase in gray matter in their frontotemporal lobe (the location of emotion processing and moral decision-making). White matter in the brain develops as a person matures into adulthood, with the brain forming interconnections. Children who just exhibited antisocial behavior without being callous and unemotional don’t have the same alterations in white and gray matter in MRI images.[ref]

The latest research points to psychopathy or antisocial personality disorder as having neurodevelopmental disorder features.[ref] In other words, something didn’t develop normally in the brain. Researchers are looking at various regions of the brain during development and finding physical differences.[ref]

Genetics vs. Epigenetics:

Genetic variants can cause an overall increase or decrease in gene expression – in other words, an increase or decrease in how well the gene works.

Other ways that gene expression can upregulate or downregulate include epigenetics.

Epigenetics is often likened to the ‘software’, while genes are the hardware. Essentially, the epigenetic process turns genes on and off for translation into proteins. Things that can cause epigenetic changes include severe childhood stress, exposure to drugs, and exposure to various environmental toxicants.

In recent studies, epigenetic changes in the way that certain genes express themselves show links to antisocial personality disorder. The findings include some of the same genes (below) that have genetic links to psychopathy, such as in MAOA (monoamine oxidase A) and serotonin receptor genes.[ref][ref] Epigenetic changes in how certain genes are expressed are linked to antisocial personality disorder.

Cool study: In a 2019 study, researchers from Finland looked at the protein expression in neurons and astrocytes, comparing psychopaths to non-psychopaths. Interestingly, the researchers did this by testing skin cells from violent prisoners, nonviolent prisoners, and non-incarcerated people. In what almost seems like a bad sci-fi plot, the researchers used the skin cells to create stem cells and then differentiated those stem cells into neurons and astrocytes (brain cell types).

The researchers then looked at which genes were expressed differently in violent offenders’ neurons compared to control subjects. The results showed that ZNF132 was markedly upregulated in the violent offenders, and CDH5 was markedly downregulated. A pseudogene of unknown function called RPL10P9 had a 10-fold upregulation in the violent prisoner’s neurons.[ref] Makes you wonder what RPL10P8 is doing in the brain?

ZNF132, a zinc-finger protein, is found throughout the body, including in the brain’s cerebral cortex.[ref] The gene encodes a protein involved in the transcription of other genes — essentially, it turns on other genes.[ref][ref]

CDH5 encodes vascular endothelial cadherin, an important protein in cell-to-cell adhesion. The protein is important for forming the lining of blood vessels and developing neurons in the brain.[ref]

Research is still ongoing regarding epigenetics, protein expression, and genetics. But the overall picture emerging shows that psychopathy is more than just genetic changes and that DNA alone cannot predict who will be a psychopath.

Psychopathy Genotype Report

Please note: Many of the variants below are fairly common, and you are likely to have some of them. Just because you have a genetic variant that increases the relative risk of psychopathy doesn’t mean you will be a callous, unemotional, immoral criminal. Instead, take this information for what it is — just one small piece of what makes you who you are.

Conclusion

Research on ASPD and psychopathy clearly points to alterations in the brain due to both genetic susceptibility and maltreatment of some sort during brain development.

The rest of this article is for Genetic Lifehacks members only. Consider joining today to see the rest of this article.

Related Articles and Topics:

Is Anxiety Genetic?

This article covers genetic variants related to anxiety disorders. Genetic variants combine with environmental factors (nutrition, sleep, relationships, etc) when it comes to anxiety. There is not a single “anxiety gene”. Instead, there are many genes that can be involved – and many genetic pathways to target for solutions.

The Warrior Gene: Understanding the Role of Monoamine Oxidase Enzymes (MAOA and MAOB)

The MAOA and MAOB genes encode enzymes that break down certain neurotransmitters. People with low MAO may be prone to mood issues in certain circumstances.

Genetics of Seasonal Affective Disorder

Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) is characterized by recurrent depression with a change in the season, usually in fall/winter for most. Scientists think this is possibly due to an aberrant response to light – either not enough brightness to the sunlight or not enough hours of light. Your genes play a big role in this responsiveness to light.

COMT – A gene that affects your neurotransmitter levels

Wondering why your neurotransmitters are out of balance? It could be due to your COMT genetic variants. The COMT gene codes for the enzyme catechol-O-methyltransferase which breaks down (metabolizes) the neurotransmitters dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine.

References:

Basoglu, Cengiz, et al. “Synaptosomal-Associated Protein 25 Gene Polymorphisms and Antisocial Personality Disorder: Association with Temperament and Psychopathy.” Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie, vol. 56, no. 6, June 2011, pp. 341–47. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371105600605.

Beitchman, Joseph H., et al. “Childhood Aggression, Callous-Unemotional Traits and Oxytocin Genes.” European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, vol. 21, no. 3, Mar. 2012, pp. 125–32. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-012-0240-6.

Chang, Hongjuan, et al. “Possible Association between SIRT1 Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms and Predisposition to Antisocial Personality Traits in Chinese Adolescents.” Scientific Reports, vol. 7, no. 1, Apr. 2017, p. 1099. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01208-2.

Checknita, D., et al. “Monoamine Oxidase A Gene Promoter Methylation and Transcriptional Downregulation in an Offender Population with Antisocial Personality Disorder.” The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, vol. 206, no. 3, Mar. 2015, pp. 216–22. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.144964.

Creswell, Kasey G., et al. “OXTR Polymorphism Predicts Social Relationships through Its Effects on Social Temperament.” Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, vol. 10, no. 6, June 2015, pp. 869–76. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsu132.

Dadds, Mark R., et al. “Polymorphisms in the Oxytocin Receptor Gene Are Associated with the Development of Psychopathy.” Development and Psychopathology, vol. 26, no. 1, Feb. 2014, pp. 21–31. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000485.

—. “Polymorphisms in the Oxytocin Receptor Gene Are Associated with the Development of Psychopathy.” Development and Psychopathology, vol. 26, no. 1, Feb. 2014, pp. 21–31. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000485.

De Dreu, Carsten K. W., et al. “Oxytonergic Circuitry Sustains and Enables Creative Cognition in Humans.” Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, vol. 9, no. 8, Aug. 2014, pp. 1159–65. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nst094.

Ducci, F., et al. “Interaction between a Functional MAOA Locus and Childhood Sexual Abuse Predicts Alcoholism and Antisocial Personality Disorder in Adult Women.” Molecular Psychiatry, vol. 13, no. 3, Mar. 2008, pp. 334–47. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.mp.4002034.

Fisher, Kristy A., and Manassa Hany. “Antisocial Personality Disorder.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 2021. PubMed, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546673/.

Fouda, Abdelrahman Y., et al. “Utility of LysM-Cre and Cdh5-Cre Driver Mice in Retinal and Brain Research: An Imaging Study Using TdTomato Reporter Mouse.” Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, vol. 61, no. 3, Mar. 2020, p. 51. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.61.3.51.

Gescher, Dorothee Maria, et al. “Epigenetics in Personality Disorders: Today’s Insights.” Frontiers in Psychiatry, vol. 9, Nov. 2018, p. 579. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00579.

Hamada, Kenichi, et al. “DNA Hypermethylation of the ZNF132 Gene Participates in the Clinicopathological Aggressiveness of ‘Pan-Negative’-Type Lung Adenocarcinomas.” Carcinogenesis, vol. 42, no. 2, Feb. 2021, pp. 169–79. Silverchair, https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgaa115.

Hollerbach, Pia, et al. “Main and Interaction Effects of Childhood Trauma and the MAOA UVNTR Polymorphism on Psychopathy.” Psychoneuroendocrinology, vol. 95, Sept. 2018, pp. 106–12. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.05.022.

—. “Main and Interaction Effects of Childhood Trauma and the MAOA UVNTR Polymorphism on Psychopathy.” Psychoneuroendocrinology, vol. 95, Sept. 2018, pp. 106–12. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.05.022.

Hotamisligil, G. S., and X. O. Breakefield. “Human Monoamine Oxidase A Gene Determines Levels of Enzyme Activity.” American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 49, no. 2, Aug. 1991, pp. 383–92.

Kolla, Nathan J., et al. “Corticostriatal Connectivity in Antisocial Personality Disorder by MAO-A Genotype and Its Relationship to Aggressive Behavior.” The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, vol. 21, no. 8, Aug. 2018, pp. 725–33. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyy035.

Li, Jingguang, et al. “Association of Oxytocin Receptor Gene (OXTR) Rs53576 Polymorphism with Sociality: A Meta-Analysis.” PLoS ONE, vol. 10, no. 6, June 2015, p. e0131820. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0131820.

Liu, Zhao, et al. “Downregulated ZNF132 Predicts Unfavorable Outcomes in Breast Cancer via Hypermethylation Modification.” BMC Cancer, vol. 21, Apr. 2021, p. 367. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08112-z.

Marzilli, Eleonora, et al. “Antisocial Personality Problems in Emerging Adulthood: The Role of Family Functioning, Impulsivity, and Empathy.” Brain Sciences, vol. 11, no. 6, May 2021, p. 687. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11060687.

—. “Antisocial Personality Problems in Emerging Adulthood: The Role of Family Functioning, Impulsivity, and Empathy.” Brain Sciences, vol. 11, no. 6, May 2021, p. 687. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11060687.

Mentis, Alexios-Fotios A., et al. “From Warrior Genes to Translational Solutions: Novel Insights into Monoamine Oxidases (MAOs) and Aggression.” Translational Psychiatry, vol. 11, Feb. 2021, p. 130. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01257-2.

—. “From Warrior Genes to Translational Solutions: Novel Insights into Monoamine Oxidases (MAOs) and Aggression.” Translational Psychiatry, vol. 11, Feb. 2021, p. 130. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01257-2.

Poore, Holly E., and Irwin D. Waldman. “The Association of Oxytocin Receptor Gene (OXTR) Polymorphisms with Antisocial Behavior: A Meta-Analysis.” Behavior Genetics, vol. 50, no. 3, May 2020, pp. 161–73. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-020-09996-6.

—. “The Association of Oxytocin Receptor Gene (OXTR) Polymorphisms with Antisocial Behavior: A Meta-Analysis.” Behavior Genetics, vol. 50, no. 3, May 2020, pp. 161–73. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-020-09996-6.

Raine, Adrian. “Antisocial Personality as a Neurodevelopmental Disorder.” Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, vol. 14, May 2018, pp. 259–89. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050817-084819.

—. “Neurodevelopmental Marker for Limbic Maldevelopment in Antisocial Personality Disorder and Psychopathy.” The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, vol. 197, no. 3, Sept. 2010, pp. 186–92. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.078485.

Rautiainen, M.-R., et al. “Genome-Wide Association Study of Antisocial Personality Disorder.” Translational Psychiatry, vol. 6, no. 9, Sept. 2016, pp. e883–e883. www.nature.com, https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2016.155.

—. “Genome-Wide Association Study of Antisocial Personality Disorder.” Translational Psychiatry, vol. 6, no. 9, Sept. 2016, pp. e883–e883. www.nature.com, https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2016.155.

Rautiainen, M-R, et al. “Genome-Wide Association Study of Antisocial Personality Disorder.” Translational Psychiatry, vol. 6, no. 9, Sept. 2016, p. e883. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2016.155.

—. “Genome-Wide Association Study of Antisocial Personality Disorder.” Translational Psychiatry, vol. 6, no. 9, Sept. 2016, p. e883. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2016.155.

Rhee, Soo Hyun, et al. “The Association Between Toddlerhood Empathy Deficits and Antisocial Personality Disorder Symptoms and Psychopathy in Adulthood.” Development and Psychopathology, vol. 33, no. 1, Feb. 2021, pp. 173–83. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579419001676.

Ruisch, I. Hyun, et al. “Interplay between Genome-Wide Implicated Genetic Variants and Environmental Factors Related to Childhood Antisocial Behavior in the UK ALSPAC Cohort.” European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, vol. 269, no. 6, 2019, pp. 741–52. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-018-0964-5.

Sanz-García, Ana, et al. “Prevalence of Psychopathy in the General Adult Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 12, Aug. 2021, p. 661044. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.661044.

Tiihonen, Jari, et al. “Neurobiological Roots of Psychopathy.” Molecular Psychiatry, vol. 25, no. 12, Dec. 2020, pp. 3432–41. www.nature.com, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0488-z.

—. “Neurobiological Roots of Psychopathy.” Molecular Psychiatry, vol. 25, no. 12, Dec. 2020, pp. 3432–41. www.nature.com, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0488-z.

Tikkanen, R, et al. “Impulsive Alcohol-Related Risk-Behavior and Emotional Dysregulation among Individuals with a Serotonin 2B Receptor Stop Codon.” Translational Psychiatry, vol. 5, no. 11, Nov. 2015, p. e681. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2015.170.

Tikkanen, Roope, et al. “The Effects of a HTR2B Stop Codon and Testosterone on Energy Metabolism and Beta Cell Function among Antisocial Finnish Males.” Journal of Psychiatric Research, vol. 81, Oct. 2016, pp. 79–86. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.06.019.

Tissue Expression of ZNF132 – Summary – The Human Protein Atlas. https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000131849-ZNF132/tissue. Accessed 3 Sept. 2021.

Verona, Edelyn, et al. “Oxytocin-Related Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms, Family Environment, and Psychopathic Traits.” Personality Disorders, vol. 9, no. 6, Nov. 2018, pp. 584–89. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000290.

Vevera, Jan, et al. “Rare Copy Number Variation in Extremely Impulsively Violent Males.” Genes, Brain, and Behavior, vol. 18, no. 6, July 2019, p. e12536. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/gbb.12536.

Viding, Essi, et al. “Antisocial Behaviour in Children with and without Callous-Unemotional Traits.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, vol. 105, no. 5, May 2012, pp. 195–200. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2011.110223.

—. “Antisocial Behaviour in Children with and without Callous-Unemotional Traits.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, vol. 105, no. 5, May 2012, pp. 195–200. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2011.110223.

Waller, Rebecca, et al. “An Oxytocin Receptor Polymorphism Predicts Amygdala Reactivity and Antisocial Behavior in Men.” Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, vol. 11, no. 8, Aug. 2016, pp. 1218–26. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsw042.

“What’s the Difference Between a Psychopath and a Sociopath? And How Do Both Differ from Narcissists?” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/story/whats-the-difference-between-a-psychopath-and-a-sociopath-and-how-do-both-differ-from-narcissists. Accessed 3 Sept. 2021.

Xu, Xiaohui, et al. “Association Study between the Monoamine Oxidase A Gene and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Taiwanese Samples.” BMC Psychiatry, vol. 7, Feb. 2007, p. 10. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-7-10.