Key takeaways:

~ Trigger points are hyperirritated knots in the muscle and fascia that can refer pain to a nearby region of the body.

~ New research involving biopsy of trigger points shows that COL1A1, a protein from type I collagen, triggers PDGFR-α receptors, causing a cascade of events that results in sustained muscle contraction at that spot and pain.

~ Genetic research on trigger points is scant, but there are common variants in COL1A1 and PDGFRA that could play a role.

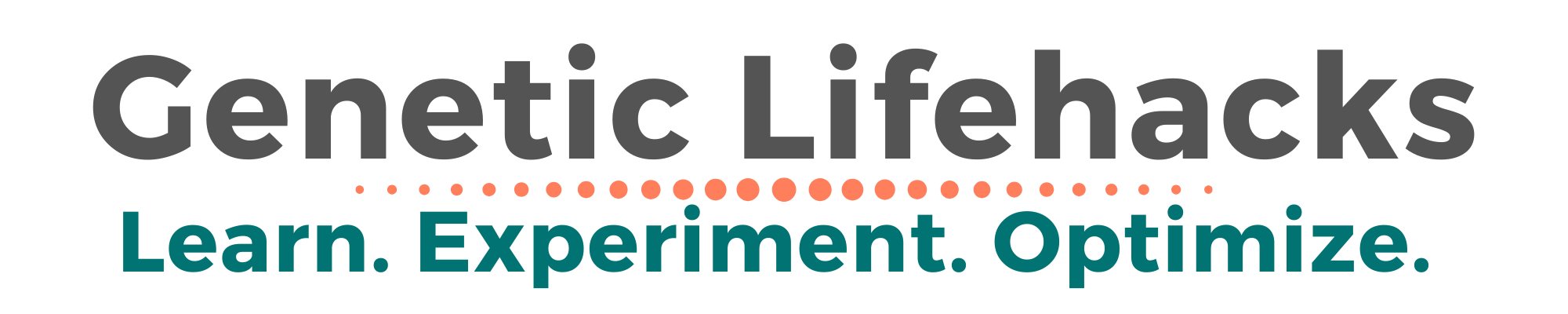

Myofascial trigger points and pain

The myofascia is the connective tissue that surrounds and supports your muscles, vessels, and organs. It’s a thin layer that makes up a network of connective tissue that helps support the body’s structure. Trigger points within the fascia can cause referred, localized muscle pain.

There are many different ways that researchers, doctors, and physiotherapists define and discuss trigger points and myofascial pain. It’s not well defined, or at least not consistent in the terminology. I’m going to include some of the more common ways it is talked about, and then go into the genetic connections and what is going on in the fascia.

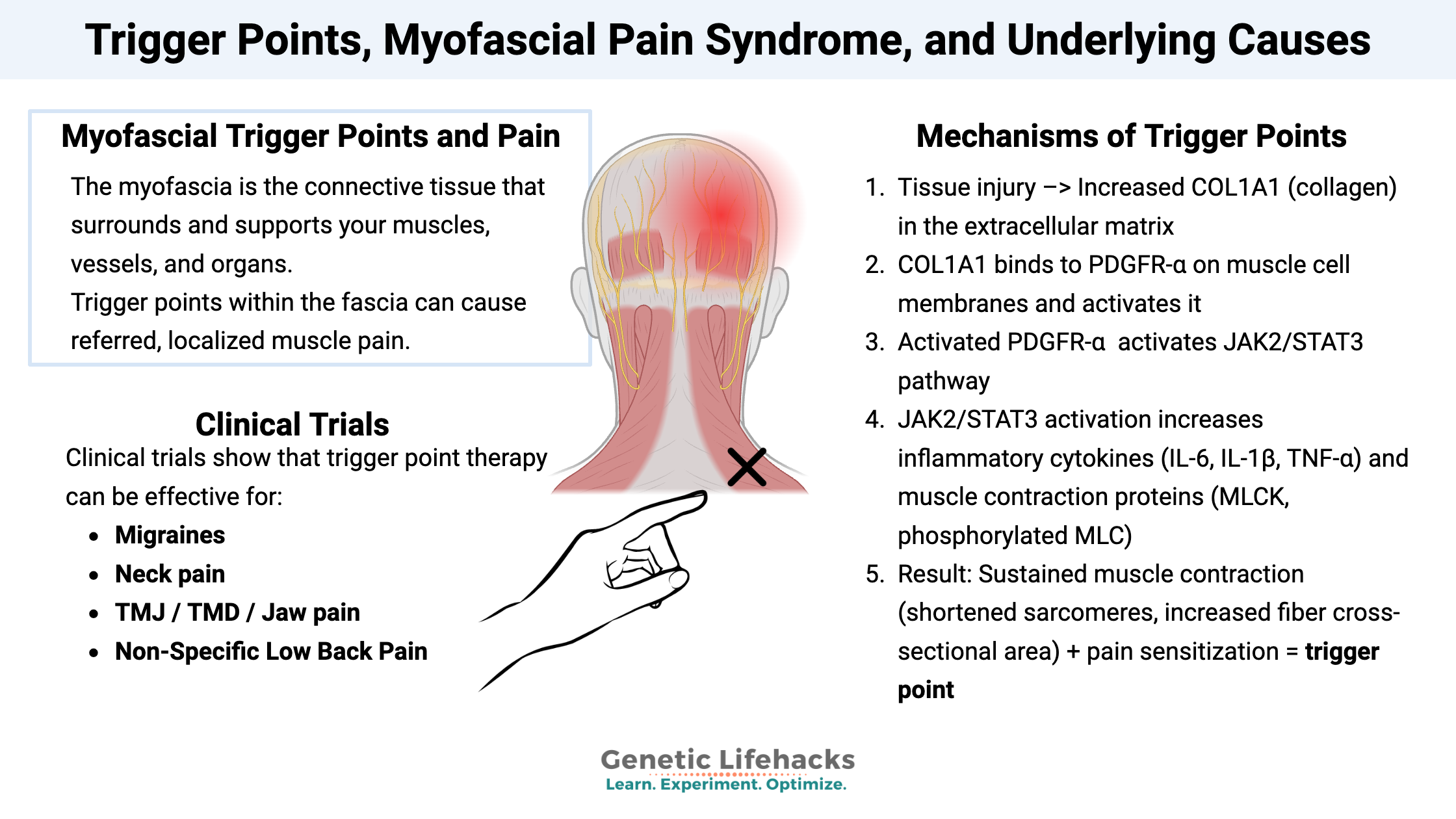

Disruption in the organization of the fascia covering muscles and organs can cause pain, referred pain, or even latent problems that flare up later. Trigger points are small knots in the fascia that are usually sharply painful when you push on them, but unnoticeable when you aren’t pushing on them. However, trigger points can be associated with referred pain — essentially, the tiny knot under the skin in one area may cause aching pain further away. For example, if your thumb joint hurts, you may have a tiny trigger point up toward your elbow that both hurts to push on, but relieves the thumb pain.

Myofascial pain syndrome (MPS) is like trigger points on steroids — frequent or chronic localized muscle pain caused by tight muscle bands with multiple trigger points. It’s considered the most common cause of pain in the clinical setting.[ref]

Trigger points can be classified as either active or latent. Active trigger points are accompanied by pain, often at a distance from the trigger point. Latent trigger points are irritable knots in the fascia that may cause some pain when pushed on, but they don’t cause referred pain.

According to Physiopedia, myofascial trigger points (active or latent) characteristics include:[ref]

- Pushing on the trigger point causes local pain and/or referred pain (e.g. pain in a muscle or joint that had existing pain).

- Compressing the muscle fibers at the trigger point rapidly may cause a twitch response – a quick contraction of the muscle fibers nearby.

- Muscle tightness around the trigger point – a taut band of muscle fibers.

- Some weakness in the muscle with the trigger point.

- Localized autonomic issues such as vasoconstriction, goose bumps, or sweating.

Initiating Causes: Triggering pain

Strains or microtears in the fascia tissue can happen for a number of reasons, big and small. In general, myofascial pain is caused by:[ref]

| Cause | Details/Summary |

|---|---|

| Trauma or muscle injury | Direct tissue damage |

| Overuse / repetitive motions | Poor posture, small repetitive movement |

| Structural problems | Arthritis, scoliosis, spondylosis—changes muscle use |

| Biochemical/Metabolic factors | Hypothyroidism, vitamin D deficiency, iron deficiency |

| Behavioral | Jaw chewing, clenching (bruxism/TMJ/TMD) |

Think about how your muscles feel when you’ve been hunched over a keyboard, working at a repetitive mechanical task, or even doing a handicraft, like sewing or knitting. Repetitive strain, often coupled with poor posture, is a big cause of myofascial pain and trigger points. Similarly, changing the way you use your muscles due to arthritis or another structural issue is another common cause of myofascial pain. Then there’s pickleball…

Another common cause of myofascial pain is from chewing or clenching the jaw. Masticatory myofacial pain is an overarching term for jaw pain from chewing or bruxism. TMJ and TMD are other terms used here.[ref]

I always find it interesting to look at how researchers create animal models of a condition. For myofascial trigger points and pain, they use a blunt strike to the muscle combined with long-term repeated eccentric exercise.[ref]

What’s going on in the muscle and fascia to cause trigger points:

A 2024 study identified the specific molecular pathway from tissue damage to trigger point formation. It went beyond just pain sensitivity and surface-level explanations to the actual mechanism creating the muscle knots. This study seems to be a breakthrough in understanding what is actually going on in trigger points.

Biopsy of trigger point tissues showed increased activation of PDGFR-α, which is a type of receptor tyrosine kinase. Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are a family of transmembrane receptors that are involved in pain transmission, and the biopsy showed significantly increased levels of several RTKs. The researchers focused on the RTK called PDGFR-α, which was highly elevated. PDGFR-α is involved in sending signals for muscle contraction and for pain. So the elevated PDGFR-α in the trigger point biopsy likely was signaling for that knot of muscle to be contracted and to be painful when compressed. The researchers then created an animal model of trigger points using a substance to increase PDGFR-α, and they were able to get rid of the trigger points by blocking PDGFR-α. The activated PDGFR-α then triggers the JAK2/STAT3 pathway, which is a signaling cascade involved in chronic pain and inflammation.[ref] PDGFR-α is encoded by the PDGFRA gene (see genotype report section below). Genetic variants in the gene are associated with the response to platelet-rich plasma therapy for elbow tendinitis.[ref]

So what activates PDGFR-α? Collagen type I α 1 (COL1A1) binds to PDGFR-α and activates it, starting the cascade of events. COL1A1 is one of the proteins that make up type I collagen, the most common type of collagen in the connective tissue, skin, and tendons. In animals, overexpression of COL1A1 causes knots of muscle contractions and pain – e.g. trigger points. The opposite was seen when COL1A1 expression was restricted.[ref]

So we have the fascia made up of connective tissue and collagen, and excess COL1A1 activates a cascade of inflammatory events. The inflammation activates a specific response in the muscles, involving TPM4 and muscle contractions, forming small knots.[ref]

Recap: Molecular mechanism[ref]

- Tissue injury causes increased COL1A1 (collagen) in the extracellular matrix

- COL1A1 binds to PDGFR-α on muscle cell membranes and activates it

- Activated PDGFR-α –> activates JAK2/STAT3 pathway

- JAK2/STAT3 activation increases inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α) and muscle contraction proteins.

- Result: Sustained muscle contraction + pain sensitization –> trigger point

Circling back to the initiation of the trigger point / myofascial pain:

COL1A1 is upregulated in injured or damaged tissue. It is also upregulated due to higher TGFβ expression, especially in relation to fibrosis.[ref][ref]

If COL1A1 sounds familiar, it is also involved in hypermobility syndromes, such as Ehlers-Danlos. Rare mutations in the COL1A1 gene (or other collagen genes) can cause the classic form of EDS with laxity in the joints. Excess COL1A1 is involved in lung fibrosis as well. Interestingly and likely important here – COL1A1 is the key to the organization of fibrils in the extracellular matrix. [ref]

Other factors that can upregulate COL1A1 include BPS (plasticizers), nicotine, and hypoxia or lack of oxygen to the tissue.[ref][ref]

Studies on cellular or biochemical processes:

The above explanation of how COL1A1 triggers the muscle knot contraction through a cascade of events that starts with PDGFR-α gives the details, but at a systems or whole body level, there are interactions with the immune system, pain transmission, and mitochondrial function.

- Vitamin D:

Vitamin D deficiency is thought to play a role in myofascial trigger points. A clinical trial found that for patients with myofascial jaw pain who also had vitamin D deficiency, correcting the vitamin D deficiency was as effective for relieving the pain as giving strong NSAIDs.[ref] - Estrogen receptors:

One study in women with myofascial pain looked at the expression of different receptors in the fascia and noted that estrogen receptor alpha was found there. The authors noted that this may be a reason for the increase in myofascial pain syndrome in women.[ref] - Depth -> pain:

A 2024 study used ultrasound imaging techniques to look at trigger points. The study found that in patients with pain, trigger points were smaller, stiffer, and deeper in the muscle tissue.[ref] - Mitochondrial function:

An animal model of myofascial pain syndrome showed decreased ATP production and mitochondrial dysfunction in muscle.[ref]

Clinical trials that apply trigger point therapy

| Condition | Intervention | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Migraines | Trigger point therapy (neck/shoulders) | Fewer, shorter migraines |

| Asthma cough | Trigger point injections vs standard therapy | Higher efficacy in coughing |

| Jaw pain (TMJ/TMD) | Manual release | Mixed results in trials |

| Neck pain | Dry needling/manual release/wet injection | Short-term benefit (dry needling was best) |

| Low back pain | Dry needling vs compression (gluteus medius) | Both are effective; compression less painful |

| Shoulder pain | Manual trigger point compression | More effective than a sham therapy |

Let’s look at the details on these trials:

Migraines:

A clinical trial involving 53 migraine patients showed that myofascial trigger point therapy on their neck and shoulders resulted in statistically fewer and shorter migraines after seven sessions. Interestingly, the researchers also tested calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) concentrations and didn’t find that trigger point therapy changed CGRP levels, even though it reduced migraines.[ref]

Note that other studies show that trigger points are only found in some migraine patients. Additionally, manual compression of the trigger points can sometimes trigger a migraine attack.[ref]

Asthma cough, chronic coughing:

Cough variant asthma is a type of asthma that involves chronic coughing with minimal wheezing. It is thought to be caused by hypersensitivity of the cough reflex. A controlled clinical trial looked at the efficacy of trigger point injections in the neck and chest muscles to eliminate the hypersensitive coughing. They compared the trigger point therapy to standard asthma treatment (budesonide-formoterol plus montelukast) and found that the trigger point therapy was quite a bit more likely to be effective. This is a study worth sharing if you know anyone with cough-variant asthma.[ref]

TMJ / TMD / Jaw pain:

Clinical studies of manual release of trigger points for myofascial jaw pain show mixed results. Some studies show that it works to relieve pain in some people, while other studies fail to show a statistically significant result.[ref]

Neck pain:

A meta-analysis of clinical trials on dry needling or manual release of trigger points for neck pain showed that both are likely to give short-term relief. Dry needling results were superior to manual trigger point release.[ref] Trigger point injections (wet needling) also work, but a meta-analysis showed that they are likely not superior to dry needling.[ref]

Non-Specific Low Back Pain:

A clinical trial compared dry needling to compression of trigger points in the gluteus medius for low back pain. Both worked to reduce back pain, but compression of trigger points was judged to be less painful.[ref] Note that this study was just comparing trigger point techniques in people who were already checked for other causes of back pain. Trigger point therapy may not be a miracle cure for all back issues…

Shoulder pain:

A small randomized controlled trial compared manual trigger point compression to sham therapy for shoulder pain due to myofascial pain syndrome. The results showed trigger point therapy to be significantly more effective than sham.[ref]

Now, let’s take a look at a few of the genetic variants in PDGFRA or COL1A1 that could interact with trigger points, and then we will take a look at the Lifehacks (solutions) for trigger points.

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related articles and topics:

References: