Key takeaways:

~ Exposure to childhood trauma, such as abuse, violence, cancer, or repeated stress, can have a long-lasting effect.

~ On average, adults who were exposed to childhood trauma have higher rates of depression, PTSD, suicide, and anxiety disorders.

~ Genetics is a big part of resilience to childhood trauma. For some, childhood trauma causes physiological changes that last a lifetime. For others, childhood trauma doesn’t cause physiological changes.

Cortisol, corticotropin-releasing hormone, and childhood trauma:

Childhood trauma, abuse, or long-term illness can cause lasting physiological effects that persist into adulthood – for some people.

Let’s take a look at the HPA axis, cortisol release, and how genetic variants shape our response to traumas.

The HPA axis:

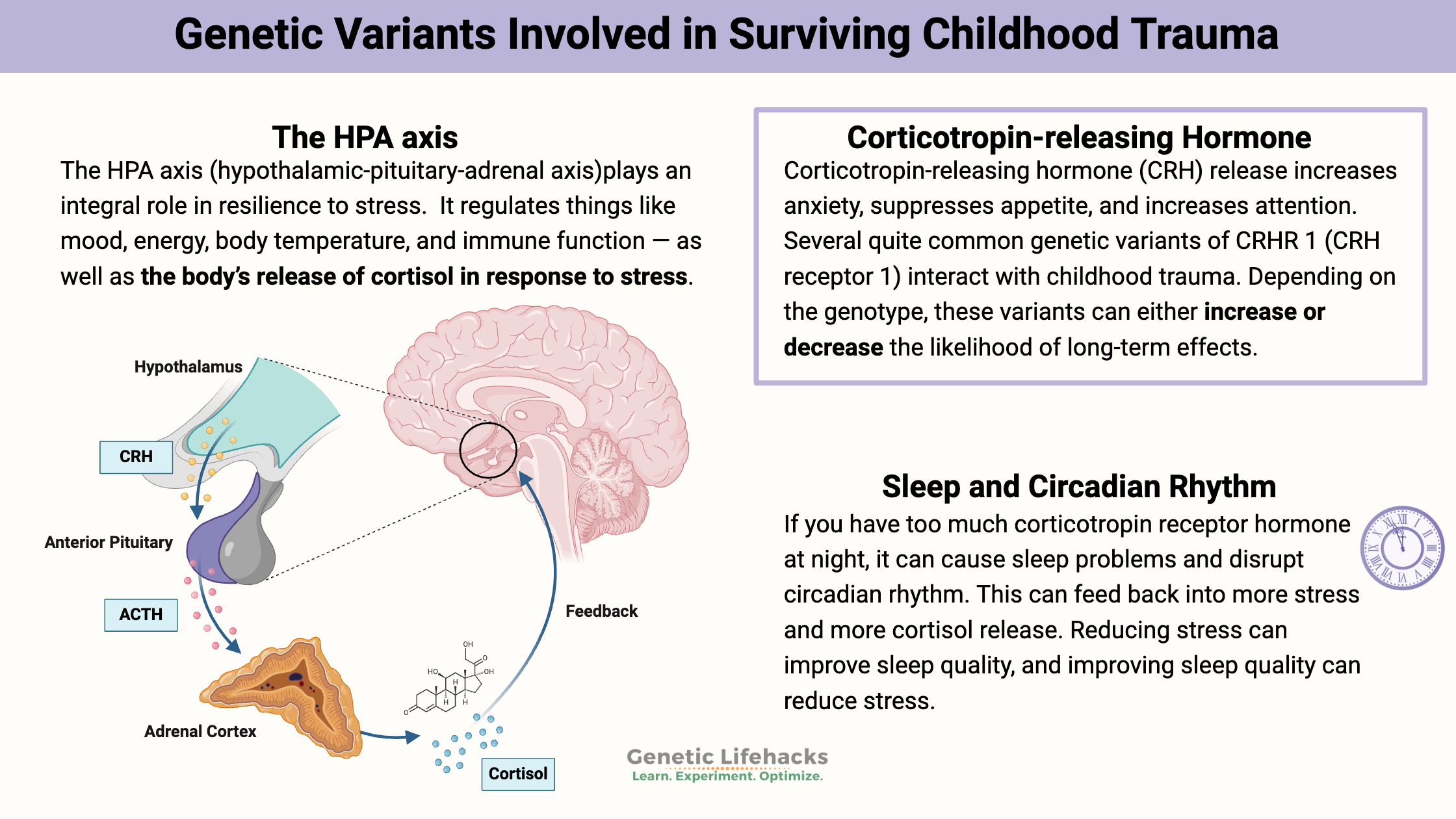

The HPA axis (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis) may play an integral role in resilience to stress. Several studies have investigated the role of the HPA axis, childhood adversity, and adult depression or anxiety.[ref] One study concluded, “A history of childhood trauma has long-standing effects on adulthood cortisol responses to stress, particularly in that depressed individuals with a history of childhood trauma show blunted cortisol responses”.[ref]

The HPA axis involves the interactions and feedback loops between the brain (hypothalamus), the pituitary gland, and the adrenal glands. It regulates things like mood, energy, body temperature, and immune function — as well as the body’s release of cortisol in response to stress.

Related Article: HPA Axis Dysfunction and Genetics

Corticotropin-releasing hormone:

Corticotropin-releasing hormone regulates the HPA axis in response to stress.

- Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is a peptide hormone that is produced mainly in the hypothalamus.

- CRH, in turn, activates ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone) in the pituitary.

- ACTH then controls the synthesis of cortisol (adrenals), mineralocorticoids, and DHEA.

This is a pathway that starts in the brain and ends with the release of hormones, such as cortisol, from the adrenal glands.

CRH release increases anxiety, suppresses appetite, and increases attention – exactly what you need when a tiger is chasing you, but not good when it is chronically a little elevated.

Cortisol and circadian rhythm:

Cortisol levels naturally rise and fall over the course of the day in rhythm with your body’s circadian clock. There can be a cascade of chronic effects if this cortisol rhythm is either out of phase or dampened.

Chronic cortisol:

The release of cortisol has a feedback loop effect on the brain, which shuts off the stress response after the threat has passed. When that feedback loop is impaired, a long-term change in cortisol levels can occur. Persistent elevation of cortisol rewires the brain in the areas that are important in emotional regulation, memory, and executive function.

CRH receptor:

CRH acts by binding to and activating the corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor CRHR1. Several quite common genetic variants of CRHR1 interact with childhood trauma. Depending on the genotype, these variants can either increase or decrease the likelihood of long-term effects from stressful events in childhood.

These genetic differences explain why some adults have lasting problems with altered cortisol levels if exposed to traumatic events in childhood or had chronic stress in their childhood.

Or, to put it the opposite way, these variants are why some adults are more resilient and have no long-term problems from childhood trauma.

Maternal stress:

Cortisol can also be passed through the placenta to a baby. A study investigating the effects of excessive maternal stress on their children found that the CRHR1 genetic variants also play a role, along with other genes, in the risk of depression in children whose mothers experienced a lot of stress during pregnancy.[ref]

A study on children in China who survived a stressful earthquake either while in the womb or as an infant showed that the CRHR1 variant (below) was associated with worsened visual-spatial memory in childhood for the variant carriers exposed as a fetus to the stress.[ref]

Resilience Genotype Report:

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks:

Talk to your doctor:

If you carry the risk variants and deal with depression or anxiety, talk with your doctor about getting your cortisol levels tested to see if your levels are lower than normal or chronically high. Ask about testing at multiple times during the day to see how your cortisol level rises and falls.

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

Cortisol and HPA Axis Dysfunction

Cortisol is a hormone produced by the adrenal glands in times of stress, and it also plays many roles in your normal bodily functions. It is a multi-purpose hormone that needs to be in the right amount (not too high, not too low) and at the right time. Your genes play a big role in how likely you are to have problems with cortisol.

Is inflammation causing your depression or anxiety?

Research over the past two decades clearly shows a causal link between increased inflammatory markers and depression. Genetic variants in the inflammatory-related genes can increase the risk of depression and anxiety.

Lithium Orotate + B12: Boosting mood and decreasing anxiety, for some people…

For some people, low-dose, supplemental lithium orotate is a game-changer for mood issues when combined with vitamin B12. But other people may have little to no response. The difference may be in your genes.

References:

Gannon, Robert L., and Mark J. Millan. “The Corticotropin-Releasing Factor (CRF)(1) Receptor Antagonists CP154,526 and DMP695 Inhibit Light-Induced Phase Advances of Hamster Circadian Activity Rhythms.” Brain Research, vol. 1083, no. 1, Apr. 2006, pp. 96–102. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.017.

Gillespie, Charles F., et al. “Risk and Resilience: Genetic and Environmental Influences on Development of the Stress Response.” Depression and Anxiety, vol. 26, no. 11, 2009, pp. 984–92. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20605.

Heim, Christine, et al. “The Link between Childhood Trauma and Depression: Insights from HPA Axis Studies in Humans.” Psychoneuroendocrinology, vol. 33, no. 6, July 2008, pp. 693–710. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.008.

Jothie Richard, Edwin, et al. “Anti-Stress Activity of Ocimum Sanctum: Possible Effects on Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis.” Phytotherapy Research: PTR, vol. 30, no. 5, May 2016, pp. 805–14. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.5584.

Panossian, Alexander, et al. “Novel Molecular Mechanisms for the Adaptogenic Effects of Herbal Extracts on Isolated Brain Cells Using Systems Biology.” Phytomedicine, vol. 50, Nov. 2018, pp. 257–84. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2018.09.204.

Suzuki, Akiko, et al. “Long Term Effects of Childhood Trauma on Cortisol Stress Reactivity in Adulthood and Relationship to the Occurrence of Depression.” Psychoneuroendocrinology, vol. 50, Dec. 2014, pp. 289–99. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.09.007.

Tyrka, Audrey R., et al. “Interaction of Childhood Maltreatment with the Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptor Gene: Effects on HPA Axis Reactivity.” Biological Psychiatry, vol. 66, no. 7, Oct. 2009, pp. 681–85. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.05.012.