Key takeaways:

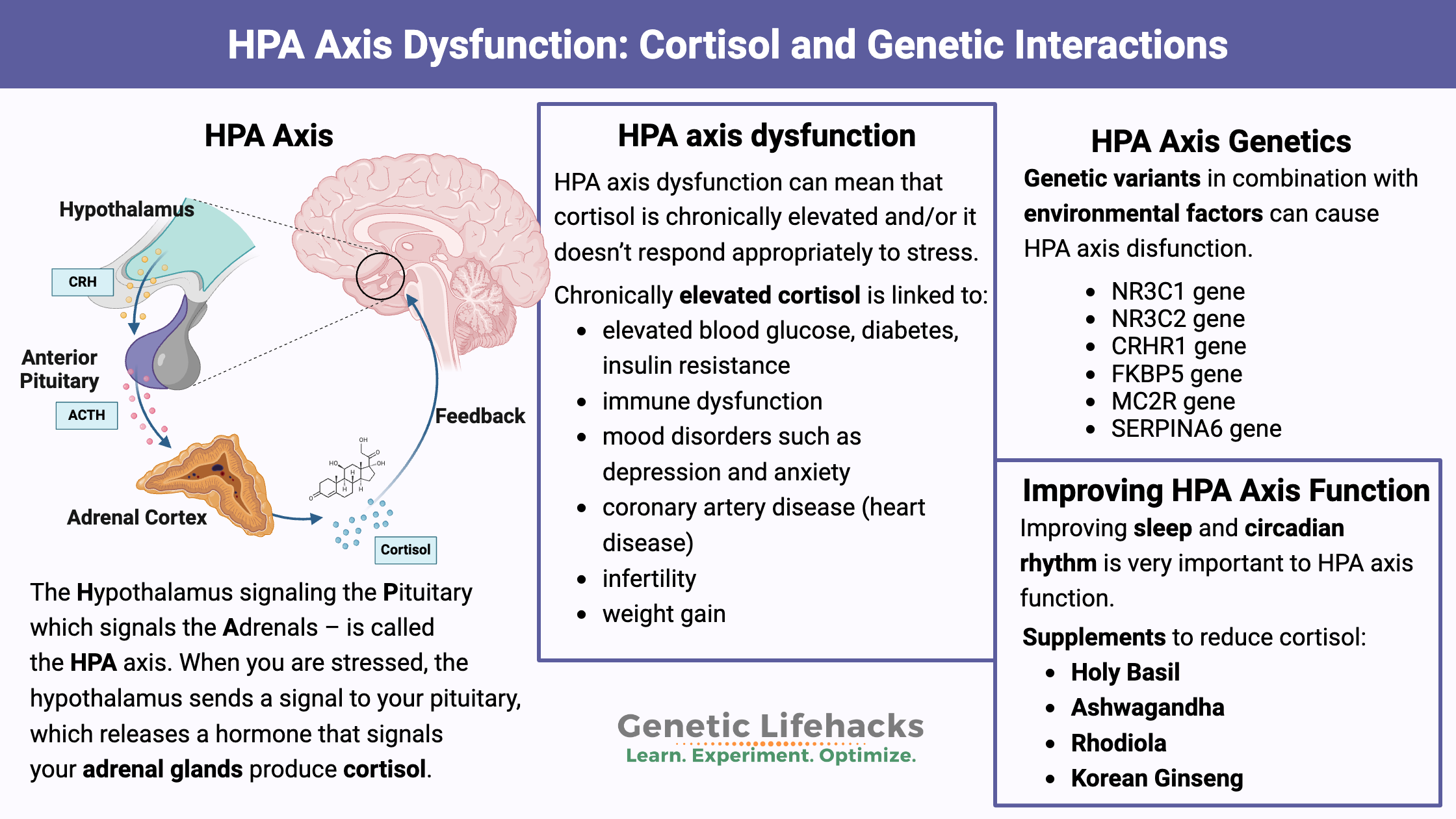

~ The HPA axis controls cortisol levels.

~ Cortisol is a hormone produced by the adrenal glands in times of stress, and it also plays many roles in your normal bodily functions.

~ Genetic variants can impact how cortisol is produced and used.

~ Stress, childhood trauma, and circadian rhythm all interact with genetics in HPA axis dysfunction.

Members will see their genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

What is the HPA Axis?

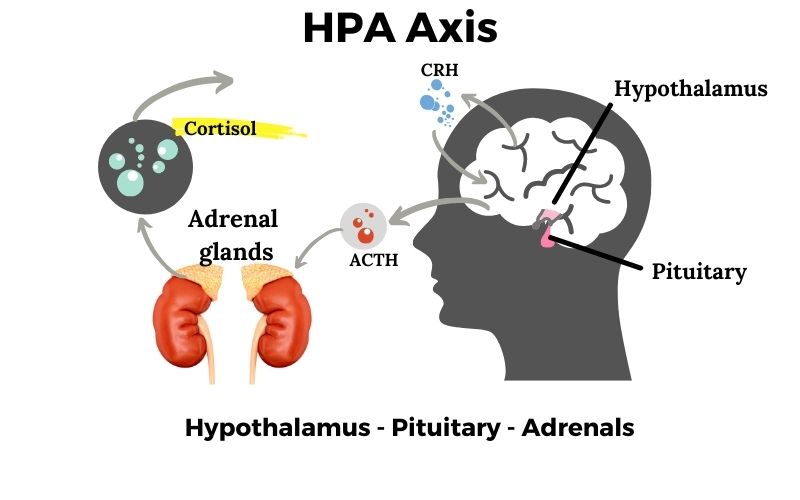

When you are stressed, your adrenal glands produce cortisol. This applies to both physical stress, like running away from a tiger, or emotional stress, such as when you mess something up at work.

Your brain controls the release of cortisol from the adrenal glands.

Specifically, a region of the brain called the hypothalamus sends a signal, called corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH), to the pituitary gland. The pituitary then releases adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which increases the production of cortisol in the adrenal cortex.[ref]

All of this together – the Hypothalamus signaling the Pituitary which signals the Adrenals – is called the HPA axis.

Getting a little more detailed: The hypothalamus releases corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH). The higher levels of CRH cause the pituitary gland, also located in the brain region, to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).

When the ACTH signal reaches the adrenal glands, it stimulates the melanocortin 2 receptor, which initiates the synthesis and release of cortisol.

It takes about 3-5 minutes for all of this to happen and for cortisol levels to rise.[ref]

What is cortisol?

Your adrenal glands produce cortisol as a way to let your whole body know what is going on in your environment. It is a signal that a stressful situation is occurring. Stress can take many forms, from physical pain to mental worry to even something you might enjoy, like exercise.[ref]

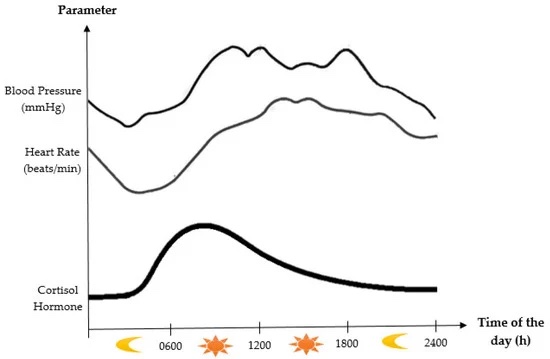

At lower levels, cortisol is secreted all the time. It has a ‘diurnal’ rhythm, which means it goes up and down over a 24-hour day in a predictable pattern.

Cortisol is a ‘steroid hormone’ which is synthesized in the adrenals from cholesterol. The signal sent by the pituitary gland for creating cortisol causes an increase in the enzyme for converting cholesterol into pregnenolone, which is the rate limiting step in creating cortisol.[ref]

Most of the time, a cortisol precursor is circulating in an inactive form, which can quickly be activated by an enzyme called hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1.

What does cortisol do in the body?

Cortisol has many functions:[ref]

- mediating the stress response

- regulating metabolism (weight gain…)

- tamping down the immune response

I’ll go into these in more detail in just a minute…

Cortisol signals for actions to take play by binding to two different receptors: mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors.

These receptors allow for the different functions of cortisol during normal vs. stress situations:[ref]

- Mineralocorticoid receptors (MR) – activated by low circulating levels of cortisol. The MR regulates a bunch of normal functions in the body.

- Glucocorticoid receptors (GR) – only activated with high levels of cortisol (stress situation). GR activates the flight-or-fight response.

Let me give you an example:

When a tiger is chasing you, cortisol is elevated to a high level. It activates the GR receptors, which kick you into high gear. While you’re escaping with your life, your body doesn’t need to waste energy on things like reproduction or even most of the immune system. Those functions can be tamped down, put aside, until the crisis has passed, and your energy can be devoted to survival for the time being.

Cortisol levels can ramp up quickly (within minutes) in times of stress, but the half-life of cortisol is also pretty quick. Within 15 minutes, half of the cortisol is metabolized into a form that is excreted in the urine.

What happens when cortisol levels are too high or too low?

The problems with cortisol come when levels are chronically elevated – or – when the response to a new stress is exaggerated and out of proportion.[ref]

There are two defined diseases for extreme cortisol dysregulation:

- Cushing’s syndrome

- Addison’s disease

Cushing’s syndrome is due to too much cortisol, either from glucocorticoid medications or too much cortisol produced by the adrenals due to a pituitary tumor. Symptoms of Cushing’s include high blood pressure, abdominal weight gain, round face, stretch marks, thin skin, and, in women, facial hair, and menstrual irregularities.

Addison’s is due to too little cortisol production. Symptoms include weight loss, muscle weakness, nausea, and mood changes.

While Cushing’s and Addison’s show the extremes of cortisol disorders, milder manifestations plague many of us.

Symptoms of HPA axis dysfunction:

HPA axis dysfunction can mean that cortisol is chronically elevated and/or it doesn’t respond appropriately to stress. It can also be due to a disrupted circadian rhythm of cortisol production over the course of the day.

HPA axis dysfunction can mean:

- chronically elevated cortisol

- inappropriate stress response

- the rhythm of cortisol is out of sync

Chronically elevated cortisol can be due to repeated stress (physical or mental), genetic susceptibility (below), and traumatic childhood events (epigenetic trigger).[ref]

Chronically elevated cortisol is linked to:

Another aspect of HPA axis dysfunction is that repeated stress and high cortisol cause ‘habituation’, essentially a downregulation of the cortisol receptors and decreased acute stress response.[ref] While this could seem like a good thing, the acute stress response is needed in times of, well, acute stress -like running from a tiger. Plus, the downregulation can also apply to normal cortisol function during times of non-stress as well.

Let’s dig into the negative effects of HPA axis dysfunction in more detail:

1) Immune dysfunction:

Chronic stress can also lead to an increase in autoimmune diseases and a decrease in normal immune responses.[ref][ref]

When acute stress occurs, the body cannot mount a normal stress response because of decreased GR receptors. It can lead to an increased susceptibility to infections, including colds.[ref]

2) Depression due to HPA axis dysfunction:

Reduced glucocorticoid receptor function along with altered cortisol circadian rhythm is found in women who have depression.[ref]

Several other studies show that higher basal levels of cortisol along with altered cortisol circadian rhythm is associated with major depressive disorder. It seems to be a two-way street — treating depression can reduce elevated cortisol levels.[ref][ref]

3) Metabolic syndrome, weight gain, and cortisol:

Hypertension, insulin resistance, and high cholesterol add up to metabolic syndrome. And obesity goes hand-in-hand here…All together, a problem that many of us face.

So what does research show about obesity and cortisol?

Activating the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) can increase blood glucose levels by stimulating the liver to create more glucose (gluconeogenesis).[ref]

Hair cortisol levels, which give an average cortisol reading for the past few months, were tested in a group of British adults. The cortisol levels in hair were higher in those who were obese (BMI >30) and with larger waist circumferences. Higher hair cortisol levels are also correlated to being overweight for a longer period of time (>4 years).[ref]

This doesn’t mean that weight gain is due to high cortisol levels for everyone, but it could be part of the problem for many of us.

4) Infertility from stress:

Constant activation of the HPA axis can cause problems when trying to conceive. It is due to cortisol shifting the ratio of follicle stimulation hormone to luteinizing hormone (FSH:LH).

The altered hormone ratio causes decreased egg quality and an increased risk of infertility.[ref][ref] Read more details here.

Additionally, chronic and unpredictable mild stress can alter menstrual cycles and decrease estradiol levels.[ref]

5) Childhood trauma alters cortisol levels in adults:

I mentioned above that cortisol levels are controlled by three factors: genetics, chronic stress, and childhood trauma.

There is quite a bit of scientific evidence showing childhood trauma can cause persistent changes in the HPA axis. One study describes it as the brain becoming sensitized, thus allowing episodes of depression to occur more frequently.[ref]

Childhood trauma can be mental or physical – from child abuse to a parent dying to having childhood leukemia. Genetics interacts with this, and some people are more resilient to childhood trauma than others. Certain genetic variants cause a higher basal cortisol level with a blunted response to actual, acute stress. It increases the risk of depression, anxiety, and PTSD.[ref]

Is adrenal fatigue real?

I wanted to quickly address adrenal fatigue because many people may confuse it with HPA axis dysfunction. It isn’t really the same thing.

Adrenal fatigue is an idea promulgated by alternative medicine practitioners. The idea is chronic stress causes the adrenals to wear out – become exhausted – and not produce enough cortisol. It is thought to cause overall fatigue, depression, weight gain, brain fog, etc. Examples of alternative health sites writing about adrenal fatigue: Dr. Northrup’s adrenal fatigue article, Dave Asprey chiming in on the adrenal fatigue idea. These are just a handful of examples, and all the big alternative health websites used to be on the adrenal fatigue band-wagon.

Most endocrinologists don’t think that ‘adrenal fatigue’ is real. And research studies back up the idea that the adrenal glands aren’t worn out, exhausted, or not producing enough cortisol.[ref][ref]

In fact, some alternative medicine practitioners seem to be revamping how they talk about adrenal fatigue and are now morphing their articles to talk about HPA axis dysfunction.[article][article]

HPA Axis Genotype Report

Lifehacks for HPA axis dysfunction:

Most of these ‘lifehacks’ involve reducing chronically high cortisol levels. If you have genetic variants tied to lower cortisol, skip down to the adaptogens info.

Changing your body’s cortisol response is going to take some time. If your cortisol receptors are downregulated because of chronic high cortisol, it may take a while to see the effects of reducing cortisol levels.

The rest of this article covers supplements and diet. It is for Genetic Lifehacks members only. Consider joining today to see the rest of this article.

Related Articles and Genes:

Uterine fibroids

Uterine fibroids are a problem for a lot of women, especially after age 30. Fibroids are benign tumors that grow in the muscle cells of the uterus. This article will dig into the causes of fibroids, explain how your genetic variants can add to the susceptibility, and offer solutions that are backed by research.

Thyroid Hormone Levels and Your Genes

The thyroid is a master regulator of many of your body’s systems. It is integrally involved in metabolism and helps maintain body temperature, heart rate, breathing, and body weight. Your genes play a big role in how well your thyroid works and how your body produces and converts the different forms of thyroid hormone.

Is Anxiety Genetic?

This article covers genetic variants related to anxiety disorders. Genetic variants combine with environmental factors (nutrition, sleep, relationships, etc) when it comes to anxiety. There is not a single “anxiety gene”. Instead, there are many genes that can be involved – and many genetic pathways to target for solutions.

Metabolic Health Topic Summary Report

Metabolic health is important for your overall well-being. From high triglycerides to high blood sugar, poor metabolic health is a risk factor for many chronic diseases. Check out the full articles for details, lifehacks, and references.

References:

Abelson, James L., et al. “HPA Axis Activity in Patients with Panic Disorder: Review and Synthesis of Four Studies.” Depression and Anxiety, vol. 24, no. 1, 2007, pp. 66–76. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20220.

Belleau, Emily L., et al. “The Impact of Stress and Major Depressive Disorder on Hippocampal and Medial Prefrontal Cortex Morphology.” Biological Psychiatry, vol. 85, no. 6, Mar. 2019, pp. 443–53. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.09.031.

Cadegiani, Flavio A., and Claudio E. Kater. “Adrenal Fatigue Does Not Exist: A Systematic Review.” BMC Endocrine Disorders, vol. 16, no. 1, Aug. 2016, p. 48. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-016-0128-4.

Chu, Lanling, et al. “Increased Cortisol and Cortisone Levels in Overweight Children.” Medical Science Monitor Basic Research, vol. 23, Feb. 2017, pp. 25–30. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.12659/msmbr.902707.

da Silva, Bruna S., et al. “Effects of Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptor 1 SNPs on Major Depressive Disorder Are Influenced by Sex and Smoking Status.” Journal of Affective Disorders, vol. 205, Nov. 2016, pp. 282–88. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.008.

Du, Xin, and Terence Y. Pang. “Is Dysregulation of the HPA-Axis a Core Pathophysiology Mediating Co-Morbid Depression in Neurodegenerative Diseases?” Frontiers in Psychiatry, vol. 6, 2015. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00032.

Garabedian, Michael J., et al. “Glucocorticoid Receptor Action in Metabolic and Neuronal Function.” F1000Research, vol. 6, 2017. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.11375.1.

—. “Glucocorticoid Receptor Action in Metabolic and Neuronal Function.” F1000Research, vol. 6, 2017. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.11375.1.

Grissom, Nicola, and Seema Bhatnagar. “Habituation to Repeated Stress: Get Used to It.” Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, vol. 92, no. 2, Sept. 2009, p. 215. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2008.07.001.

Hacimusalar, Yunus, and Ertuğrul Eşel. “Suggested Biomarkers for Major Depressive Disorder.” Archives of Neuropsychiatry, vol. 55, no. 3, May 2018, pp. 280–90. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.5152/npa.2017.19482.

“Home.” Bulletproof, https://www.bulletproof.com/. Accessed 22 Nov. 2021.

“Is Adrenal Fatigue Real?” Dr. Jolene Brighten, 12 Mar. 2016, https://drbrighten.com/adrenal-fatigue-isnt-real/.

Is Adrenal Fatigue “Real”? – Harvard Health. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/is-adrenal-fatigue-real-2018022813344. Accessed 22 Nov. 2021.

Jackson, Sarah E., et al. “Hair Cortisol and Adiposity in a Population‐based Sample of 2,527 Men and Women Aged 54 to 87 Years.” Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), vol. 25, no. 3, Mar. 2017, pp. 539–44. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21733.

Jarcho, Michael R., et al. “Dysregulated Diurnal Cortisol Pattern Is Associated with Glucocorticoid Resistance in Women with Major Depressive Disorder.” Biological Psychology, vol. 93, no. 1, Apr. 2013, pp. 150–58. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.01.018.

Joseph, Dana N., and Shannon Whirledge. “Stress and the HPA Axis: Balancing Homeostasis and Fertility.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 18, no. 10, Oct. 2017, p. 2224. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18102224.

Joseph, Joshua J., et al. “Diurnal Salivary Cortisol, Glycemia and Insulin Resistance: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.” Psychoneuroendocrinology, vol. 62, Dec. 2015, pp. 327–35. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.08.021.

Joseph, Joshua J., and Sherita H. Golden. “Cortisol Dysregulation: The Bidirectional Link between Stress, Depression, and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 1391, no. 1, Mar. 2017, pp. 20–34. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13217.

Juruena, Mario F. “Early-Life Stress and HPA Axis Trigger Recurrent Adulthood Depression.” Epilepsy & Behavior: E&B, vol. 38, Sept. 2014, pp. 148–59. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.10.020.

Leventhal, Stacey M., et al. “Uncovering a Multitude of Human Glucocorticoid Receptor Variants: An Expansive Survey of a Single Gene.” BMC Genetics, vol. 20, 2019. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12863-019-0718-z.

Lin, Ruby C. Y., et al. “Association of Obesity, but Not Diabetes or Hypertension, with Glucocorticoid Receptor N363S Variant.” Obesity Research, vol. 11, no. 6, June 2003, pp. 802–08. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2003.111.

Majer-Łobodzińska, Agnieszka, and Joanna Adamiec-Mroczek. “Glucocorticoid Receptor Polymorphism in Obesity and Glucose Homeostasis.” Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine: Official Organ Wroclaw Medical University, vol. 26, no. 1, Feb. 2017, pp. 143–48. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.17219/acem/41231.

McLachlan, Kaitlyn, et al. “Dysregulation of the Cortisol Diurnal Rhythm Following Prenatal Alcohol Exposure and Early Life Adversity.” Alcohol (Fayetteville, N.Y.), vol. 53, June 2016, pp. 9–18. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcohol.2016.03.003.

Nezi, Markella, et al. “Corticotropin Releasing Hormone And The Immune/Inflammatory Response.” Endotext, edited by Kenneth R. Feingold et al., MDText.com, Inc., 2000. PubMed, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279017/.

—. “Corticotropin Releasing Hormone And The Immune/Inflammatory Response.” Endotext, edited by Kenneth R. Feingold et al., MDText.com, Inc., 2000. PubMed, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279017/.

NM_000176.3(NR3C1):C.66G>A (p.Glu22=) AND Glucocorticoid Resistance, Relative – ClinVar – NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/RCV000017536.30/. Accessed 22 Nov. 2021.

Northrup, Christiane and M.D. “Do You Have Adrenal Fatigue?” Christiane Northrup, M.D., 7 Apr. 2020, https://www.drnorthrup.com/adrenal-fatigue/.

Ortega, Van A., et al. “Evolutionary Significance of the Neuroendocrine Stress Axis on Vertebrate Immunity and the Influence of the Microbiome on Early-Life Stress Regulation and Health Outcomes.” Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 12, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.634539.

Pagliaccio, David, et al. “Stress-System Genes and Life Stress Predict Cortisol Levels and Amygdala and Hippocampal Volumes in Children.” Neuropsychopharmacology, vol. 39, no. 5, Apr. 2014, pp. 1245–53. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2013.327.

—. “Stress-System Genes and Life Stress Predict Cortisol Levels and Amygdala and Hippocampal Volumes in Children.” Neuropsychopharmacology, vol. 39, no. 5, Apr. 2014, pp. 1245–53. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2013.327.

Schalinski, Inga, et al. “The Cortisol Paradox of Trauma-Related Disorders: Lower Phasic Responses but Higher Tonic Levels of Cortisol Are Associated with Sexual Abuse in Childhood.” PLoS ONE, vol. 10, no. 8, Aug. 2015, p. e0136921. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136921.

Spencer, Robert L., and Terrence Deak. “A USERS GUIDE TO HPA AXIS RESEARCH.” Physiology & Behavior, vol. 178, Sept. 2017, p. 43. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.11.014.

Stetler, Cinnamon, and Gregory E. Miller. “Depression and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Activation: A Quantitative Summary of Four Decades of Research.” Psychosomatic Medicine, vol. 73, no. 2, Mar. 2011, pp. 114–26. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820ad12b.

—. “Depression and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Activation: A Quantitative Summary of Four Decades of Research.” Psychosomatic Medicine, vol. 73, no. 2, Mar. 2011, pp. 114–26. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820ad12b.

Szczepankiewicz, Aleksandra, et al. “Glucocorticoid Receptor Polymorphism Is Associated with Major Depression and Predominance of Depression in the Course of Bipolar Disorder.” Journal of Affective Disorders, vol. 134, no. 1–3, Nov. 2011, pp. 138–44. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.020.

Thau, Lauren, et al. “Physiology, Cortisol.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 2021. PubMed, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538239/.

—. “Physiology, Cortisol.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 2021. PubMed, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538239/.

Valkenburg, O., et al. “Genetic Polymorphisms of the Glucocorticoid Receptor May Affect the Phenotype of Women with Anovulatory Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), vol. 26, no. 10, Oct. 2011, pp. 2902–11. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/der222.

—. “Genetic Polymorphisms of the Glucocorticoid Receptor May Affect the Phenotype of Women with Anovulatory Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.” Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), vol. 26, no. 10, Oct. 2011, pp. 2902–11. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/der222.

van Rossum, E. F. C., and E. L. T. van den Akker. “Glucocorticoid Resistance.” Endocrine Development, vol. 20, 2011, pp. 127–36. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1159/000321234.

—. “Glucocorticoid Resistance.” Endocrine Development, vol. 20, 2011, pp. 127–36. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1159/000321234.