Key takeaways:

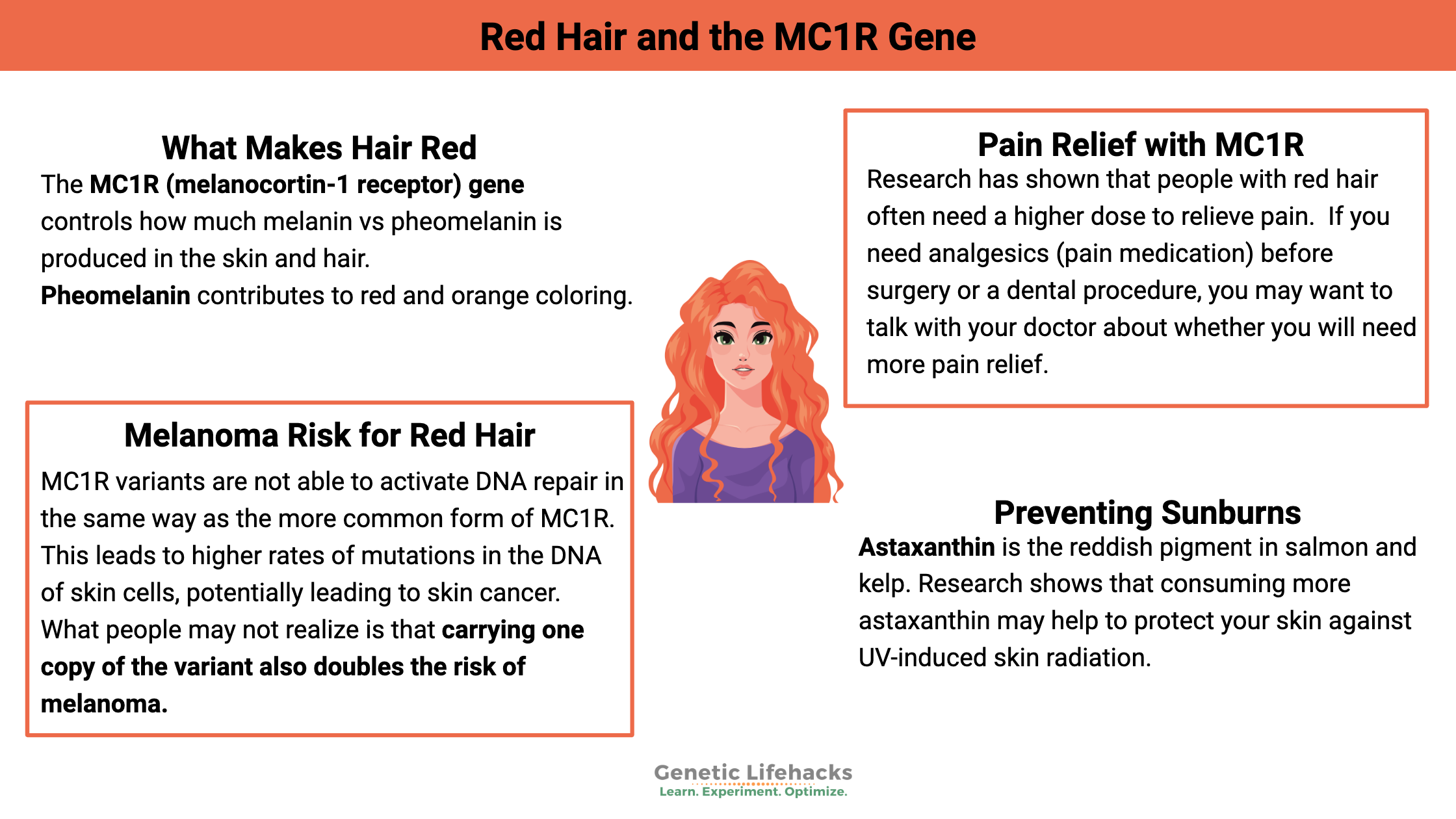

~ Genetic variants in the MC1R gene cause changes in hair pigment, resulting in red hair for people with two copies of the variants.

~ Even without red hair, people with one copy of the MC1R variants are at a higher risk for skin cancer.

Hair Color Genes: What Makes it Red?

I remember learning about Punnet squares in high school; people with dark hair had the dominant hair color gene, and the redhead gene was recessive. Turns out it’s not nearly as simple as having a red hair gene or a brown hair gene. (Nor is there a blue eye gene or a short gene… my high school biology class wasn’t right on several things.) Instead, certain variants in the MC1R gene control red pigmentation in the hair.

The genetic variant that causes red hair also affects other aspects of our health. Carrying the variant can cause an increased risk of melanoma and may also affect the way you respond to certain painkillers.

There are two types of pigments for hair color: eumelanin and pheomelanin.

- Eumelanin comes in either black or brown, with varying amounts responsible for ranges of hair color from blond (low eumelanin) to black (high eumelanin).

- Pheomelanin contributes to red and orange coloring.

- Most people have both eumelanin and pheomelanin, and the varying amounts of each protein contribute to the wide range of hair colors that people naturally have.

The MC1R (melanocortin-1 receptor) gene controls how much melanin vs pheomelanin is produced in the skin and hair. Genetic variants of MC1R produce different amounts of pheomelanin, with increased pheomelanin causing red hair and skin to be more photosensitive.

Melanoma Risk for Red Hair:

It is also believed that the variant forms of MC1R are not able to activate DNA repair in the same way as the more common form of MC1R. This leads to higher rates of mutations in the DNA of skin cells, potentially leading to skin cancer.[ref]

The link to melanoma is well established for the common MC1R variants that cause red hair, but what people may not realize is that carrying one copy of the variant also doubles the risk of melanoma.[ref]

Freckles and moles are also genetic:

The MC1R gene is also linked to freckles and more moles on the skin.[ref] Additionally, one MC1R variant (rs1805008) has also been tied to an increased risk of Parkinson’s disease.[ref]

Analgesics and Pain Relief with MC1R SNPs:

Kappa-opioid analgesics may act differently in women with red hair. If you need analgesics (pain medication) before surgery or a dental procedure, you may want to talk with your doctor about whether you will need more pain relief. Research has shown that people with red hair often need a higher dose to relieve pain – depending on the type of analgesic used.[ref]

A study in 2005 found that lidocaine wasn’t quite as effective for blocking pain, and that redheads were also more sensitive to both cold pain and heat pain. The study, though, was fairly small and only included 30 red-haired people.[ref] More recent and larger studies have failed to replicate the sensitivity to pain and lack of response to analgesics.[ref]

Beyond red hair in people: MC1R function

MC1R isn’t just a human-specific gene; it causes pigmentation variation in animals from chickens to goats to fish. It is also thought to be involved in the browning reaction of cut apples being exposed to air.

Beyond the ‘red hair’ gene, predicting hair color from genetic data can be tricky. Here is a great article on 124 genes that influence hair color.

Additionally, a lot of men who carry one copy of the MC1R variant may notice that their beard hair is reddish, especially in the sunlight. The Irish call this a ‘gingerbeard’.

MC1R & Redhair Genotype Report:

Lifehacks for MCR1:

Common sense dictates watching your sun exposure and avoiding a sunburn if you carry one of the risk variants listed above for melanoma.

While you need a certain amount of sun for vitamin D production, knowing when to cover up or put on sunscreen is important. In other words – avoid staying in the sun to the point that your skin starts to turn pink.