Key takeaways:

~Skin cancer is the most common type of cancer, with 1 million cases being diagnosed in the United States each year.[ref]

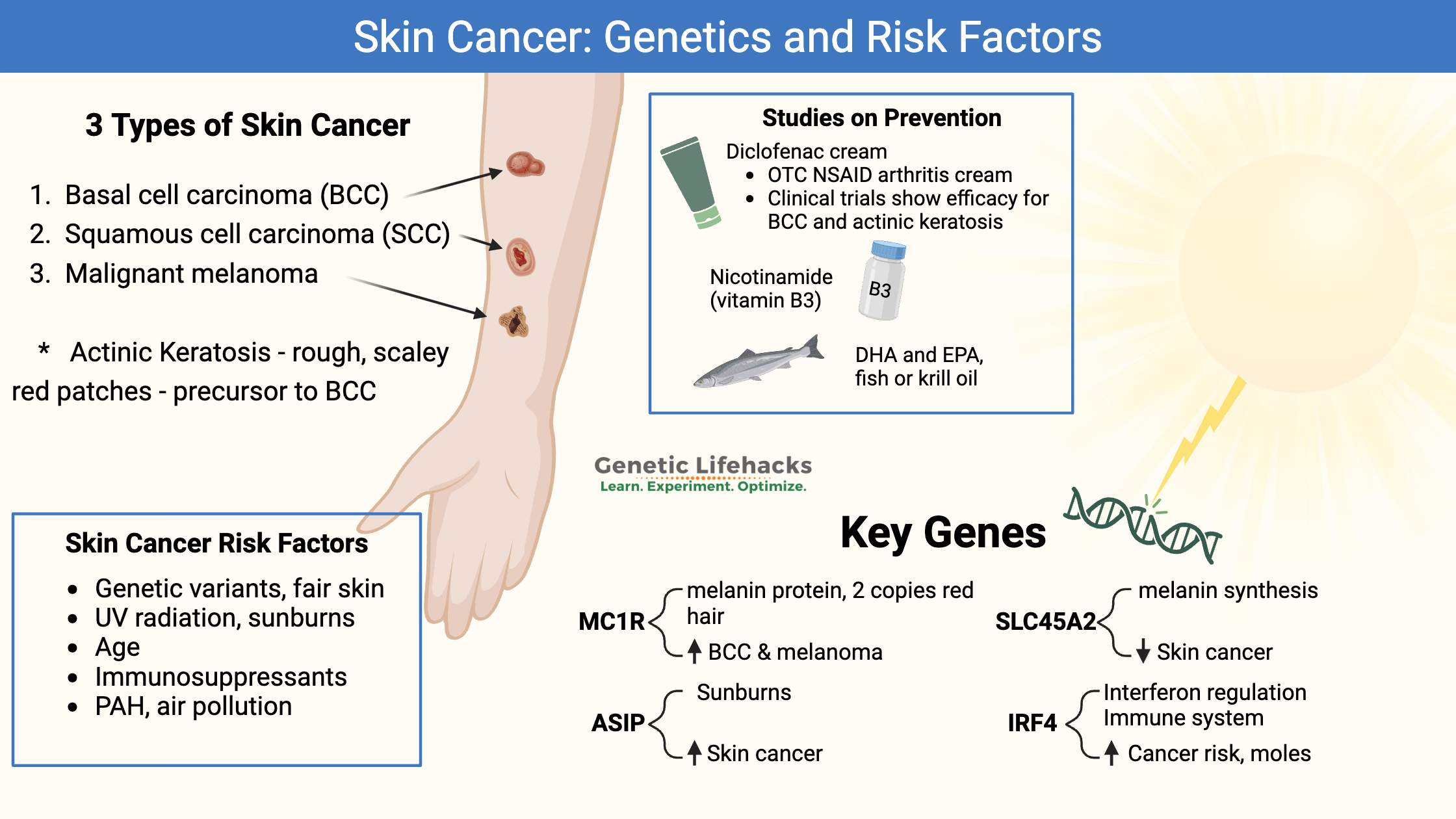

~ The three main types of skin cancer, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma, each has its own set of risks and preventative measures.

~ Sun exposure, genetic variants, age, and fair skin are all risk factors for skin cancer.

Members will see their genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

Skin Cancer Types, Genetics, and Risk Factors:

The Skin Cancer Foundation estimates that about 1 in 5 people in the US will get skin cancer by the age of 70.[ref] Other regions around the world vary in skin cancer risk based on sun exposure and the typical skin color of the population.

There are three different types of skin cancer:[ref]

- basal cell carcinoma

- squamous cell carcinoma

- melanoma

Basal Cell Carcinoma:

The most frequent type of skin cancer is basal cell carcinoma (BBC), which seldom metastasizes or spreads. This form of skin cancer is the least deadly and is easily surgically removed, especially in the early stages. Sun exposure can cause this type of skin cancer. Click here for images of the different types of BCC.

Squamous cell carcinoma:

Squamous cell carcinomas are the second most common type of skin cancer. It is curable if caught early, but there is a risk of metastasis to the lymph nodes, so it must be treated as soon as possible. These are often sun (or UV) induced cancers.

Malignant Melanoma:

Melanomas are dark, irregularly shaped skin cancers. These are the least common but most dangerous types of skin cancer because they can metastasize rapidly. They can arise from a mole (nevus) or a thickened patch of sun-damaged skin (solar elastosis).[ref]

Actinic keratosis: precursor

Actinic keratosis is a red, scaley, and dry patch of skin that can be pre-cancerous. Actinic keratosis is fairly common in older, fair-skinned people in skin areas that are exposed to a lot of sun and sunburns. [ref]

How does UV radiation cause skin cancer?

Cancer arises through DNA mutations in tumor suppressor genes or oncogenes. UV-B radiation can cause breaks in the nuclear DNA, and when the cells divide, this can cause a change (mutation) in a tumor suppressor or oncogene that then allows cancer to arise.

Up to 95% of the time, skin cancer mutations include UV-radiation-induced changes to the TP53 gene, which codes for a tumor suppressor.[ref] In melanoma, a common mutation that arises in the tumor cells is in the CDKN2A gene, which encodes a tumor suppressor gene. Very rare inherited mutations in the gene can also increase the risk for melanoma.[ref][ref]

What are the risk factors for skin cancer?

Genetics:

Genetic variants increase the risk of skin cancer (covered in detail below). But genes alone don’t cause skin cancer. Instead, it is the combination of genetic variants along with lifestyle and environmental risk factors for skin cancer.[ref]

UV radiation:

We need sun exposure on our skin to produce vitamin D, but this is a double-edged sword… the UV radiation from the sun also increases the risk of skin cancer. Avoid getting sunburned, and instead, be sure to cover up after getting a reasonable amount of sun exposure.

PAH (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons ) exposure:

People exposed to higher amounts of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are at a higher risk for skin cancer. Occupations such as iron and steel production, roofing, road paving, chimney sweeping, and aluminum production can increase exposure to PAHs. Air pollution is another source of PAH exposure.[ref]

Tattoos:

A large study involving Danish twins clearly shows that tattoos increase the risk of skin cancer (and lymphoma). Small tattoos increase skin cancer relative risk by 34% while tattoos larger than the palm of the hand increase the relative risk of skin cancer by 137%.[ref]

Age:

As we age, the ability of the body to detect and fight off cancer decreases. Thus, like other cancers, the risk of skin cancer increases with age.

Fair skin:

People with genetic variants (below) that cause a fairer skin color are at an increased risk of skin cancer.

Immunosuppressant Drugs:

Organ transplant patients are at a 100-fold increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.[ref] Immunosuppressants increase the risk of skin cancer due to increasing susceptibility to viral infections, such as HPV and herpes virus, which trigger the changes that cause skin cancer.[ref]

Skin Cancer Genotype Report:

Lifehacks:

If you have questions about an odd-looking skin patch, get it checked out by your doctor or a dermatologist.

The earlier skin cancer is detected, the more likely you will have a good outcome.

ABCD skin cancer rule:

Do you wonder what ‘odd-looking’ means when it comes to a mole? The ABCD rule for skin cancer determines if a mole or irregular dark spot is possibly a melanoma.

- Asymmetry – the mole is asymmetric

- Border irregularity – mole border is not smooth

- Color – different colors in the pigmented area

- Diameter – if the spot is larger than 6 mm in diameter

Prevention before BCC or SCC occurs:

Actinic keratosis is rough, scaley patches of skin in areas exposed to the sun. It often occurs in older people and can be a precursor to basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma.[ref]

Clearing up actinic keratosis with topical ointments may help to prevent SCC. Obviously, you’ll want to consult your doctor or a dermatologist before trying a topical option to make sure the actinic keratosis isn’t already cancerous.

Diclofenac (NSAID cream):

Multiple studies have shown that diclofenac sodium 3% gel can help some people clear actinic keratosis. One study found that 58% of the participants cleared the actinic keratosis in a month with daily application of diclofenac sodium, while another study found 45% clearance at three months. A clinical trial showed 58% clearance after 120 days.[ref][ref][ref]

Diclofenac is available over-the-counter as an arthritis cream (1% gel). Talk with your doctor if you have any questions on whether any medication is right for you. There is a possibility of rare heart-related side effects with diclofenac at prescription doses.[ref]

Ingenol mebutate is another topical option that has been used in clinical trials to clear up actinic keratosis. It is an Rx cream in the US that is derived from the sap of Euphorbia peplus (milkweed, petty spurge).[ref][ref] There are also topical Euphorbia peplus (milkweed) creams available without a prescription, but I didn’t find clinical trials on anything other than the specific ingenol mebutate cream.

Topical rapamycin:

A Genetic Lifehacks member alerted me to the research on topical rapamycin for preventing actinic keratosis. Rapamycin is an mTOR inhibitor that is also used as a senolytic. Cell studies show that mTOR is upregulated in actinic keratosis and SCC as well as in basal cell carcinomas. Rapamycin is effective in blocking mTOR upregulation.[ref][ref] Oral rapamycin has been used in clinical trials as part of the treatment of SCC.[ref]

Clinical trials for topical skin cancer:

For BCC, surgery to remove the skin is usually the safest option, especially for high-risk tumors. Low-risk or early BCC may have other options, such as topical treatments.[ref]

Your dermatologist can give you more information that is relevant to your specific case. However, here is information on some of the clinical trials for topical treatments for educational purposes.

Diclofenac is readily available in an over-the-counter NSAID arthritis cream. Studies show that diclofenac causes apoptosis in carcinoma cells.[ref][ref] A phase II clinical trial investigated 3% diclofenac cream, applied twice a day, to basal cell carcinoma (under a doctor’s continuing observation). The trial included 64 people with superficial BCC and 64 people with nodular BCC. After 8 weeks, there was a reduction in proliferation and 64% of the participants had complete clearance of the superficial BCC. However, the nodular BCC did not regress.[ref] This is something to talk with your dermatologist about and not something to undertake without medical advice.

Other topical treatments have also been studied for their efficacy in non-melanoma skin cancer. Your dermatologist may offer prescription options for topical creams that prevent or treat BCC, such as imiquimod, piroxicam, or 5-FU with salicylic acid. All of these have efficacy for BCC.[ref][ref][ref][ref]

Cell line studies show that zinc sulfate inhibits melanoma cell proliferation, survival, and migration by inhibiting HIF1a. [ref]

Research on Natural Supplements for Skin Cancer Protection:

Related Articles and Topics:

References:

Berman, Brian, et al. “Polypodium Leucotomos – An Overview of Basic Investigative Findings.” Journal of Drugs in Dermatology : JDD, vol. 15, no. 2, Feb. 2016, pp. 224–28. PubMed Central, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5189711/.

Binstock, M., et al. “Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms in Pigment Genes and Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer Predisposition: A Systematic Review.” The British Journal of Dermatology, vol. 171, no. 4, Oct. 2014, pp. 713–21. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.13283.

Boffetta, P., et al. “Cancer Risk from Occupational and Environmental Exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons.” Cancer Causes & Control: CCC, vol. 8, no. 3, May 1997, pp. 444–72. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1018465507029.

Chen, Andrew C., et al. “A Phase 3 Randomized Trial of Nicotinamide for Skin-Cancer Chemoprevention.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 373, no. 17, Oct. 2015, pp. 1618–26. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1506197.

Corchado-Cobos, Roberto, et al. “Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma: From Biology to Therapy.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 21, no. 8, Apr. 2020, p. 2956. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21082956.

Denny, Joshua C., et al. “Systematic Comparison of Phenome-Wide Association Study of Electronic Medical Record Data and Genome-Wide Association Study Data.” Nature Biotechnology, vol. 31, no. 12, Dec. 2013, pp. 1102–10. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2749.

Gibbs, David C., et al. “Association of Interferon Regulatory Factor-4 Polymorphism Rs12203592 With Divergent Melanoma Pathways.” JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 108, no. 7, Feb. 2016, p. djw004. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djw004.

Kvaskoff, Marina, et al. “Polymorphisms in Nevus-Associated Genes MTAP, PLA2G6, and IRF4 and the Risk of Invasive Cutaneous Melanoma.” Twin Research and Human Genetics: The Official Journal of the International Society for Twin Studies, vol. 14, no. 5, Oct. 2011, pp. 422–32. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1375/twin.14.5.422.

Lindelöf, B., et al. “Incidence of Skin Cancer in 5356 Patients Following Organ Transplantation.” The British Journal of Dermatology, vol. 143, no. 3, Sept. 2000, pp. 513–19.

Maccioni, Livia, et al. “Variants at Chromosome 20 (ASIP Locus) and Melanoma Risk.” International Journal of Cancer, vol. 132, no. 1, Jan. 2013, pp. 42–54. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.27648.

Moon, Debbie. “Genetics of Red Hair.” Genetic Lifehacks, 18 Apr. 2020, https://www.geneticlifehacks.com/the-redhead-gene/.

Morgan, Michael D., et al. “Genome-Wide Study of Hair Colour in UK Biobank Explains Most of the SNP Heritability.” Nature Communications, vol. 9, no. 1, Dec. 2018, p. 5271. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07691-z.

Nan, Hongmei, et al. “Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Novel Alleles Associated with Risk of Cutaneous Basal Cell Carcinoma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma.” Human Molecular Genetics, vol. 20, no. 18, Sept. 2011, pp. 3718–24. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddr287.

Nazarali, S., and P. Kuzel. “Vitamin B Derivative (Nicotinamide)Appears to Reduce Skin Cancer Risk.” Skin Therapy Letter, vol. 22, no. 5, Sept. 2017, pp. 1–4.

Scatozza, Francesca, et al. “Nicotinamide Inhibits Melanoma in Vitro and in Vivo.” Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research: CR, vol. 39, no. 1, Oct. 2020, p. 211. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-020-01719-3.

Siewierska-Górska, A., et al. “Association of Five SNPs with Human Hair Colour in the Polish Population.” Homo: Internationale Zeitschrift Fur Die Vergleichende Forschung Am Menschen, vol. 68, no. 2, Mar. 2017, pp. 134–44. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchb.2017.02.002.

Singh, Madhulika, et al. “New Enlightenment of Skin Cancer Chemoprevention through Phytochemicals: In Vitro and In Vivo Studies and the Underlying Mechanisms.” BioMed Research International, vol. 2014, 2014, p. 243452. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/243452.

“Skin Cancer Facts & Statistics.” The Skin Cancer Foundation, https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/skin-cancer-facts/. Accessed 14 May 2022.

Stacey, Simon N., et al. “Common Variants on 1p36 and 1q42 Are Associated with Cutaneous Basal Cell Carcinoma but Not with Melanoma or Pigmentation Traits.” Nature Genetics, vol. 40, no. 11, Nov. 2008, pp. 1313–18. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.234.

Stefanaki, Irene, et al. “Replication and Predictive Value of SNPs Associated with Melanoma and Pigmentation Traits in a Southern European Case-Control Study.” PloS One, vol. 8, no. 2, 2013, p. e55712. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055712.

Sulem, Patrick, et al. “Two Newly Identified Genetic Determinants of Pigmentation in Europeans.” Nature Genetics, vol. 40, no. 7, July 2008, pp. 835–37. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.160.

Tagliabue, E., et al. “MC1R Gene Variants and Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer: A Pooled-Analysis from the M-SKIP Project.” British Journal of Cancer, vol. 113, no. 2, July 2015, pp. 354–63. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.231.

—. “MC1R Gene Variants and Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer: A Pooled-Analysis from the M-SKIP Project.” British Journal of Cancer, vol. 113, no. 2, July 2015, pp. 354–63. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.231.

Tell-Marti, Gemma, et al. “The MC1R Melanoma Risk Variant p.R160W Is Associated with Parkinson Disease.” Annals of Neurology, vol. 77, no. 5, May 2015, pp. 889–94. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.24373.

Zaorska, Katarzyna, et al. “Prediction of Skin Color, Tanning and Freckling from DNA in Polish Population: Linear Regression, Random Forest and Neural Network Approaches.” Human Genetics, vol. 138, no. 6, 2019, pp. 635–47. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-019-02012-w.