Key takeaways:

~ Mosquitoes are more attracted to some people due to volatile compounds on the skin.

~ The size and itchiness of mosquito bites are due to reactions to the mosquito saliva.

~ Genetic variants affect both attractiveness to mosquitoes and the size of the bite reaction.

Members will see their genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

Why do I always get bitten by mosquitoes?

Perhaps it is in your genes…

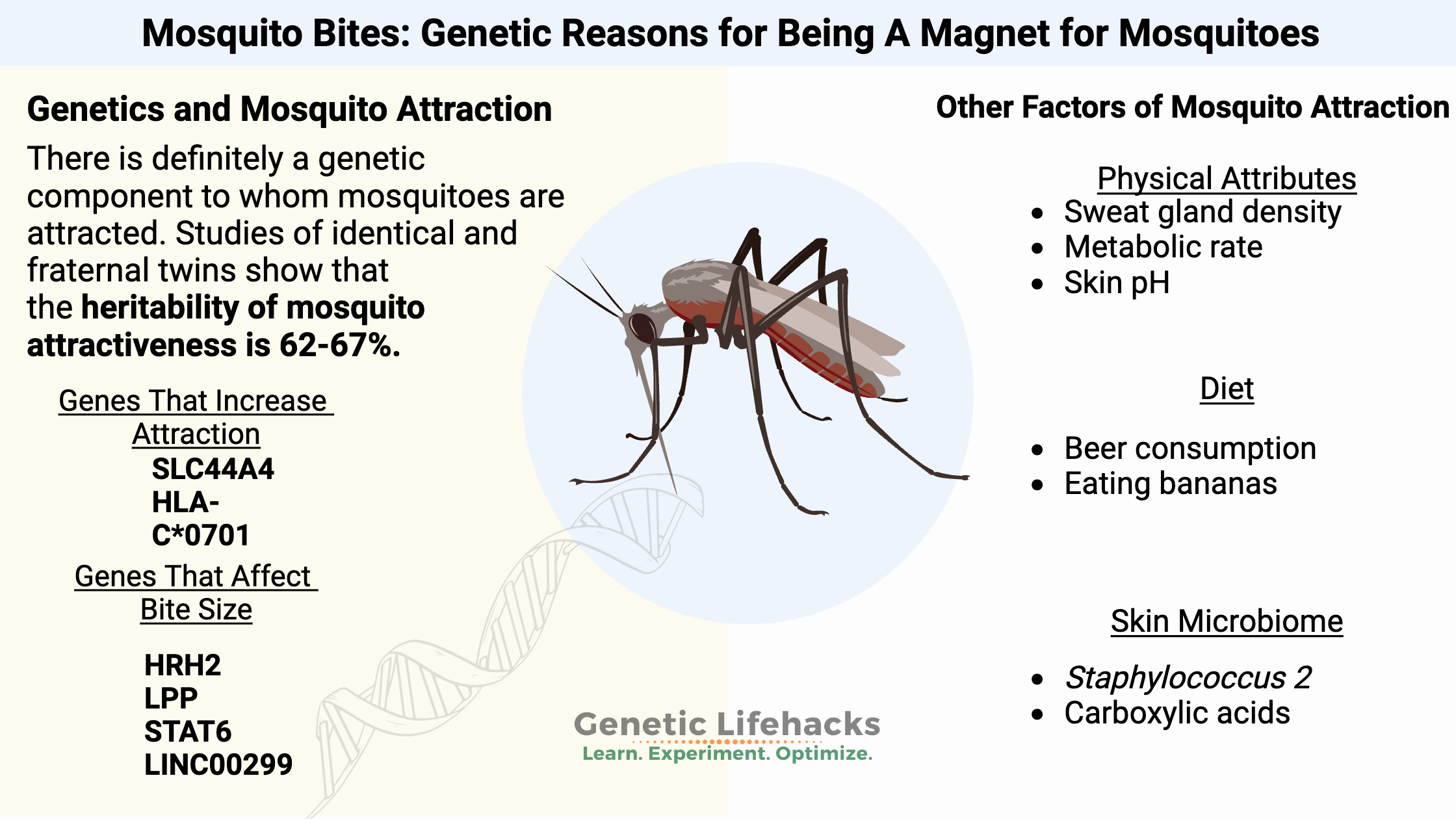

There is definitely a genetic component to whom mosquitoes are attracted. Studies of identical and fraternal twins show that the heritability of mosquito attractiveness is 62-67%. This is similar to the range of heritability for height or IQ![ref]

What makes someone attractive to mosquitoes?

People vary in the production of certain substances that attract mosquitoes. Factors such as sweat gland density, metabolic rate, and skin pH levels can explain why different people produce varying amounts of lactic acid, which attracts mosquitoes.

Additionally, the amount of carbon dioxide, ammonia, and other compounds released by individuals depends on their metabolic rate, body mass, and respiratory activity. These variations are important to consider because they show that the rates at which people release these substances can change depending on the circumstances. Various factors, including pregnancy, malaria infection, skin bacteria, diet, and genetics, contribute to the individual characteristics of mosquito attractants.[ref]

Mosquitoes use various cues, such as humidity, heat, and visual and olfactory cues, to navigate, land, and find food sources. They are attracted to certain chemicals emitted by humans, such as carbon dioxide, lactic acid, acetone, and ammonia. These chemicals, known as “kairomones” or “mosquito attractants,” help mosquitoes distinguish humans from other animals. Kairomones are substances that facilitate interactions between different species, benefiting only the species that receives the chemical signal. However, some mosquito species cannot effectively discriminate between humans and other primate odors.[ref]

Mosquitos and Your Diet:

Have you ever wondered if mosquitoes are attracted to you because of what you eat? Turns out there is some truth to that.

Researchers have found that:[ref][ref]

- Drinking beer increases human attractiveness to mosquitoes.

- Eating bananas also increases human attractiveness to mosquitoes.

Skin Microbiome:

Our skin microbiome – the bacteria and microorganisms on our skin – also plays a role in determining how attractive we are to mosquitoes. These microorganisms contribute to the production of different volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that cause body odor. There are more than 500 VOCs found in our skin secretions, including acids, alcohols, aldehydes, esters, and ketones. The mosquitoes that transmit malaria, called Anopheles mosquitoes, respond to specific VOCs such as heptanal, lactic acid, propanoic acid, and 1-octen-3-one, in both their electrophysiological and behavioral reactions. Researchers have developed synthetic odor blends containing human VOCs for use in mosquito traps, and these have shown some success.

One study found differences in the composition of the skin microbiome between individuals who were poorly and highly attractive to mosquitoes. For example, Staphylococcus 2 species on the skin was four times more abundant in the highly attractive group compared to the poorly attractive group. The skin microbiome species were associated with the VOCs known to be attractive to Anopheles mosquitoes. The study also found that the production of propanoic acid, which is associated with being unattractive to mosquitoes, was more prevalent in the poorly attractive participants compared to the highly attractive ones.[ref]

Researchers have found that knocking out the carboxylic acid receptor in mosquitoes makes them less likely to seek out and bite people. The study examined the role of skin compounds, particularly carboxylic acids, in attractiveness to Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. The researchers found that people with higher levels of these compounds on their skin were more attractive to mosquitoes. They also found that these levels remained stable over time, indicating a potential genetic component in which microbes live on your skin.[ref]

Carboxylic acids are organic acids containing a carboxyl group (COOH). Researchers have found that when carboxylic acids are combined with ammonia and lactic acid on the skin, they are highly attractive to mosquitoes.[ref]

Size of the mosquito bite:

Some people swell up with huge, itchy bites, while others just end up with a small welt that goes away fairly quickly.

Genetic studies have found several different variants that affect bite size. A histamine receptor variant has been implicated in bite size, as have genes related to the allergic response. (See genotype report below)

What happens when you are bitten by a mosquito?

When a mosquito bites you, there is a little bit of tissue damage, along with mosquito saliva injected into the skin. Often, mosquitoes will carry viruses or bacteria in their saliva, which is injected into your skin along with some of your own skin bacteria.

Researchers have cut the salivary gland in mosquitoes, creating a mosquito that can still bite but that doesn’t inject its saliva into the bite. Those mosquito bites that don’t involve saliva also don’t swell up and itch.[ref]

The immediate reaction to the bite – the swelling and itching – is due to mast cell activation. Mast cells are part of the immune system and activation releases histamine and inflammatory mediators.[ref]

Related article: Mast Cell Activation Syndrome

A recent study looked at skin biopsies of mosquito bites at 30 minutes, 4 hours, and 48 hours post-bite. The researchers found that IL-4 and IL-13, which are inflammatory cytokines were upregulated, as were interferon-gamma and IL-10 signaling. Essentially, there is a quick innate immune response to the bite. Neutrophils and macrophages were quickly recruited to the area, with T cells arriving by 48 hours after the bite.[ref]

Related article: IL-13 genetic variants and the Th2 immune shift

Mosquito Bite Genotype Report:

Members: Log in to see your data below.

Not a member? Join here.

Why is this section is now only for members? Here’s why…

Lifehacks:

DEET:

The “gold standard” for mosquito repellant is DEET. While effective, it’s important to know that DEET is absorbed through the skin. After 6 hours, between 9 – 56% is circulating systemically. There are a few case studies published showing seizures are possible in children following DEET being applied on the skin, however, most of those case studies are fairly old.[ref][ref]

Permethrin is another insecticide used to treat bed nets and clothing. You can read about how your body reacts to permethrin and other pyrethroids here: Permethrin – genes involved in metabolism

I’ll let you weigh the pros and cons of DEET versus more natural mosquito repellents that may not work as well…

Natural Mosquito Repellants: Research Studies

Related Articles:

ABCC11 and Body Odor:

Some people have ABCC11 variants that cause them to have no body odor.

ADHD Genes:

Find out how your genetic variants impact the different pathways involved in ADHD.