Key takeaways:

~ The ABCB1 gene encodes P-glycoprotein, which transports toxins and drugs out of cells.

~ Changes in ABCB1 gene expression or genetic variations cause some people to need more or less of the medications that are moved out of cells by this transporter.

~ Genetic variants can interact with medications, natural supplements, and even some foods to change the efficacy of drugs.

What does ABCB1 do?

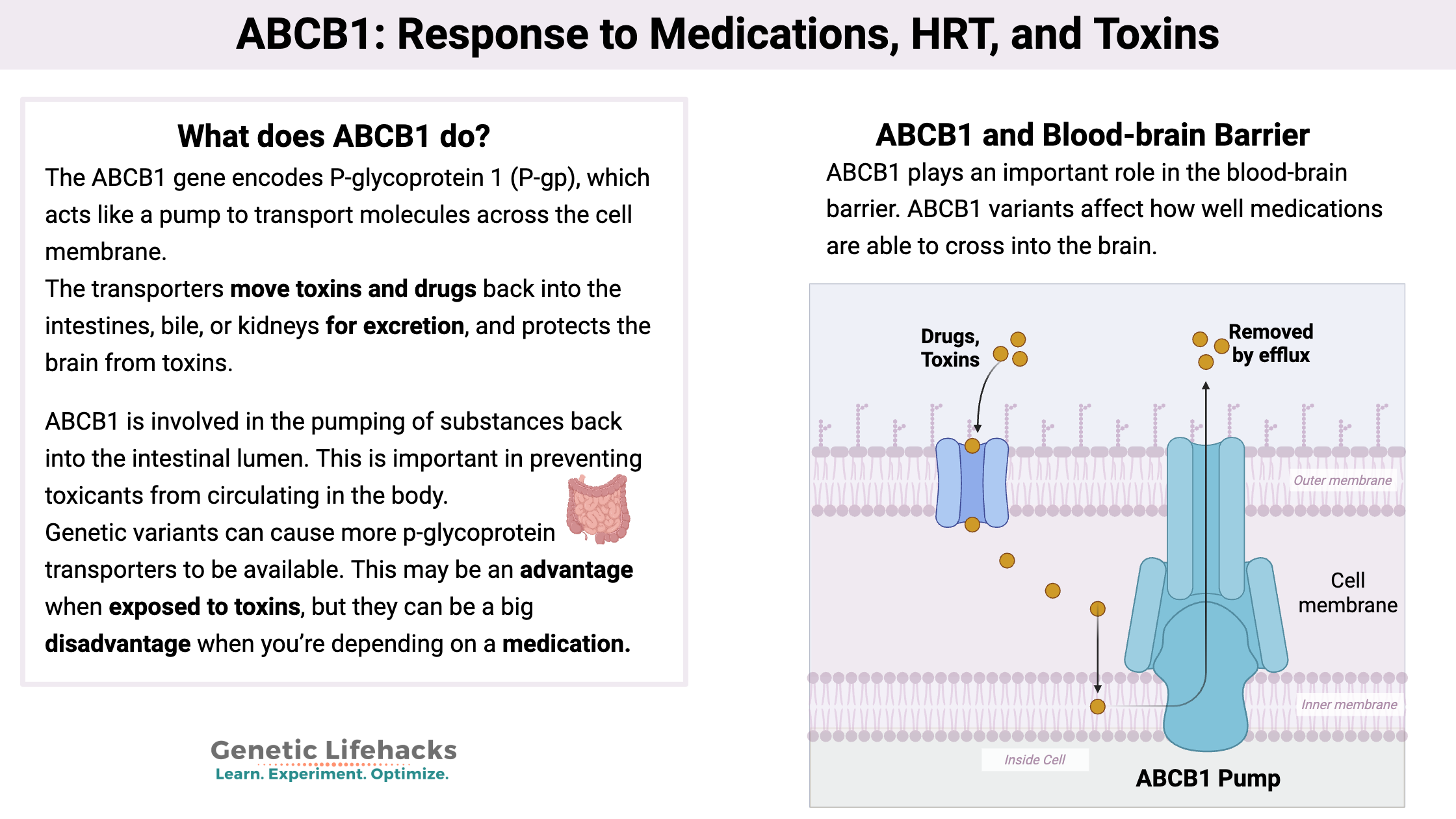

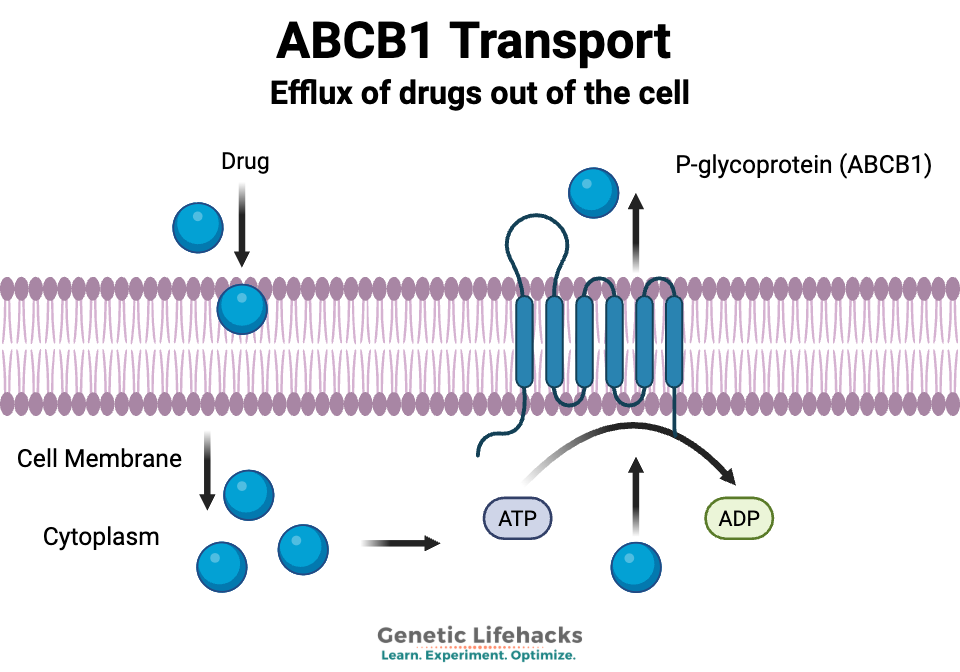

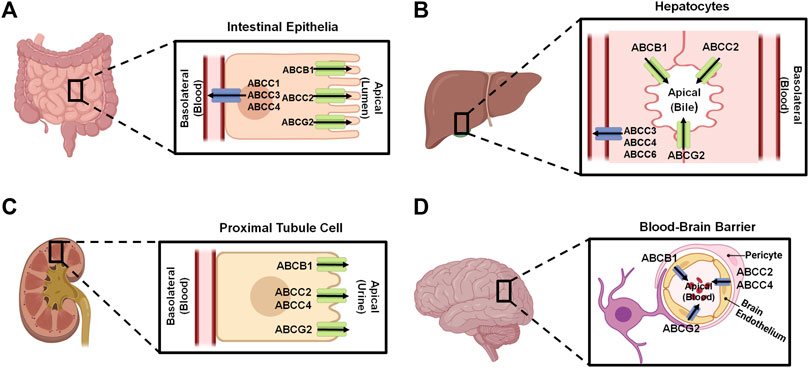

The ABCB1 gene encodes P-glycoprotein 1 (P-gp), which acts as a pump to transport molecules across the cell membrane. It is found primarily in the lining of the intestines, kidneys, skin, placenta, and the blood-brain barrier, helping to keep toxins out of important organs and the brain.[ref][ref]

Certain medications and toxins are transported back out of cells by this ATP-Binding Cassette transporter protein, ABCB1.

You’ll also see it referred to in older studies as MDR1, because it was first identified as a multi-drug resistance gene. Genetic variants in ABCB1 cause resistance to certain cancer medications, which are transported out of cells as toxins.

Where is ABCB1 found?

ABCB1 transporters are primarily active in the intestines, liver, kidneys, placenta, and blood-brain barrier. The transporters move toxins and drugs back into the intestines, bile, or kidneys for excretion, and they protect the brain and fetus from toxins.

Let’s take a look at some of these systems in more detail.

ABCB1 in the intestines:

In the epithelial cells lining your intestines, ABCB1 (P-glycoprotein) is involved in the pumping of substances back into the intestinal lumen. This is important in preventing toxicants in food or water from circulating in the body.

Excreting toxins (and drugs):

The P-glycoprotein transporter also plays a role in moving substances made in the body to the intestines for excretion. This is a great system for eliminating toxins and substances that need to be excreted, but the problem with the system is that it affects medications, especially chemotherapy. Imagine swallowing a medication: it dissolves, gets absorbed, and then part of that gets pumped back into the intestines to be eliminated.

Genetic connection:

Genetic variants in ABCB1 can cause more P-glycoprotein transporters to be available to pump medications back out of the body. The variants may be an advantage when exposed to specific toxins, but they can be a big disadvantage when you’re depending on a medication, such as an antidepressant or chemotherapy drug, to work.

Bacterial components:

Recent research shows that ABCB1 also plays a direct role in “exporting inflammatory bacterial products from host epithelia.” Small molecules produced by the gut bacteria can cross into the epithelial cells lining the intestines. Some of the molecules are inflammatory or toxic, and the ABCB1 transporter moves them back into the intestinal lumen for excretion. Mice that have the ABCB1 transporter knocked out in the intestines will spontaneously develop inflammatory bowel disease.[ref][ref]

Related article: Gut Mucosal Barrier: Foundational and Underappreciated

ABCB1 (p-glycoprotein) also plays a role in preventing bacteria from attaching to the intestinal epithelial barrier. Decreased ABCB1 levels allow more bacteria to attach to the lining of the intestines, which then increases intestinal inflammation. It is thought that ABCB1 secretions are changing the local environment to one that is inhospitable to bacterial adhesion.[ref]

ABCB1 and the blood-brain barrier:

In the 1990s, experiments and accidental lab findings showed that ABCB1 plays an important role in the blood-brain barrier.

There’s an interesting story on how this was discovered. One of the drugs that ABCB1 transports out of cells is ivermectin. A mouse model that had the ABCB1 gene knocked out had been bred at a lab, and then there was an outbreak of mites. The standard treatment was ivermectin, which was well tolerated by the wild-type mice but actually caused neurotoxicity in the ABCB1 knockout mice at the same dose. The researchers discovered that without the ABCB1 gene, the mice had a 90-fold higher accumulation of ivermectin in their brains.[ref]

ABCB1’s role in the blood-brain barrier is to protect the brain from toxic substances. Many medications are also affected by ABCB1, and variants play a role in whether the medication is able to cross into the brain at a sufficient concentration.[ref]

Alzheimer’s connection:

One endogenous substance that ABCB1 transports across the blood-brain barrier is amyloid-beta. This makes ABCB1 expression important in the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease, and substances that upregulate ABCB1 may help to prevent the accumulation of amyloid-beta plaque in the brain.[ref] There isn’t a straightforward association, though, between genetic variants and amyloid-beta accumulation. There are a lot of interactions to take into consideration with ABCB1.[ref] Gene-gene interaction studies do identify ABCB1 as influencing Alzheimer’s pathology.[ref]

Related article: How to Find Your APOE Type in Your Genetic Data

Parkinson’s connection:

A study involving French farmers showed that ABCB1 gene expression plays a role in the risk of Parkinson’s from organochlorine pesticides. Those farmers with genetic variants that decreased ABCB1 expression had a much higher risk of Parkinson’s disease.[ref]

Related article: Parkinson’s Disease: Genetics plus Environmental Factors

ABCB1 in the skin barrier function:

ABCB1 is also found in skin cells and plays a role in the barrier that the skin provides us, keeping toxins out and also affecting the response to topical medications. Expression of ABCB1 is highest in hair follicles and sweat glands, which means that ABCB1 likely plays a role in exporting toxins through sweat.

ABCB1 genetic variants affect the response to topical steroids, topical antihistamines, ivermectin, tetracycline, antifungals, and retinoid acids.[ref]

Gene expression and ABCB1:

Genetic variants impact your natural baseline ABCB1 levels, but this transporter is also affected by a number of other factors in the body. Gene expression is the process by which a gene is transcribed into mRNA and then translated into its protein.

There are multiple ways that gene expression can be changed for ABCB1. Let’s look at a few of them.

MicroRNAs and ABCB1:

MicroRNAs are short strands of RNA that can bind to an mRNA and prevent it from being translated into its protein. There are microRNAs that bind to the ABCB1 translated mRNA and prevent it from being transcribed into the transporter protein.

In this way, specific microRNAs can reduce the number of ABCB1 transporters, which then increases the amount of a drug that stays in a cell. (Alternatively, this would also mean more of a toxin would remain in a cell.)

For ABCB1, researchers have found that miR-451, miR-27a, and miR-331-5p reduce the expression of the transporter.[ref] Mir-451 is involved in modulating the immune response.[ref]

Atorvastatin reduces ABCB1 transporters. Researchers have recently discovered that microRNAs likely play a role in the interaction of atorvastatin and ABCB1. They found miR-491-3p expression is upregulated by atorvastatin, which then decreases ABCB1 in liver cells.[ref]

Hormones impact ABCB1 levels:

Studies show that both progesterone and several forms of estrogen increase the number of ABCB1 transporters. This means that supplemental hormones are upregulating ABCB1, which could impact an individual’s response to medications. Genetic variants matter here also. Some variants, such as rs2229109 G1199A (below in genotype report), have about twice the upregulation of ABCB1 in response to exogenous hormones applied topically. [ref]

Keep in mind that increased ABCB1 may be beneficial for excreting toxins from the body. A study in women trying to get pregnant found that having been on hormonal birth control may help to reduce the negative effects of persistent organic pollutants when it comes to getting pregnant.[ref]

Diet and the gut microbiome also affect ABCB1 levels:

Foods that you eat can also affect ABCB1. For example, grapefruit juice affects ABCB1, and genistein from soy milk and miso is an inhibitor of ABCB1. Splenda, a commonly used sugar alternative, increases P-glycoprotein in rats.[ref][ref] More in the lifehacks section on natural vitamins and polyphenol supplements that affect ABCB1.

Two-way street: P-glycoprotein levels affect the gut microbiome, but certain bacteria in the gut can also affect P-glycoprotein levels. A recent study showed that the gut bacteria the the Eggerthella family increase drug absorption by secreting a molecule that post-translationally inhibits P-glycoprotein.[ref]

Genetic variants and ABCB1:

Genetic variants in ABCB1 affect how much of the substance stays in the cell compared to how much gets excreted back out of the cell.

In general, it is a good thing for the body to get rid of a substance that it thinks might be toxic. But when it comes to medications, this can create problems and variations in how well they work and their effectiveness at a given dosage.

Genetic variants are found at different frequencies depending on ancestry. Thus, some medications may frequently be needed in different amounts, depending on the population group. Understanding your specific genetic variants can help dial in your likely response; however, please keep in mind that genetic research may not be as applicable if the participants of the study were of a different population background.[ref]

ABCB1 Genotype Report:

This section covers many, but not all, of the ABCB1 genetic variants. Thus, you can’t determine with certainty what your ABCB1 response will be — this only shows if you have variants, but you can’t rule anything out with it.

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks:

Understanding your genetic variants is only part of the picture here. Quite a few supplements and medications also interact with ABCB1 – either inducing it to be expressed at higher levels or blocking it from working.

Please be sure to talk with your doctor or pharmacist if you have any questions about a medication or interactions with supplements.

Inhibitors of ABCB1 (P-glycoprotein):

Keep in mind that inhibiting ABCB1 may be beneficial if you are trying to keep a specific medication in the cells. It is a technique used with chemotherapy. However, in general, inhibiting ABCB1 may not be good in the long term, as it may allow toxins to enter the cell that can damage it.

ABCB1 inhibitors include (partial list):[ref][ref – long list here][ref]

- Cyclosporine

- Certain antihistamines

- Atorvastatin

- Amitryptyline

- Clarithriomycin

- Disulfiram

- Erythromycin

- Tamoxifen

- Tacrolimus

- Sirolimus

- Simvastatin

- Quinine

- Omeprazole

- Fluoxetine

- Carvedilol

- Apixaban

- Dabigatran

Natural supplements that inhibit ABCB1:[ref]

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related articles and topics:

DPYD (Dihydropyridine Dehydrogenase) and 5-fluorouracil Reactions

References: