Key takeaways:

~This article looks at the role of cannabinoid receptors in the body, focusing on the role that endocannabinoids (cannabinoids produced in the body) and their receptors play in metabolism, inflammation, and obesity.

~Genetic variants in your cannabinoid genes can increase the risk of obesity.

~ Hacking your endocannabinoid system may be a good option for weight loss for people with specific variants.

Endocannabinoids: Driving Food Consumption

What drives us to eat? We spend a lot of time working to make money to buy food, prepare food, and consume food. It is a basic need of all animals, and without an innate drive to seek out food, we would perish. This is where our endocannabinoid system comes into play.

Cannabis may be the first thing that comes to mind when learning about the body’s cannabinoid receptors. And yes, cannabis acts upon the cannabinoid receptors, activating them and causing pleasant effects on mood, decreased pain, as well as an increase in appetite. But our endocannabinoid system is not just there for producing pleasure when smoking weed. It has one very basic biological action of rewarding food consumption.

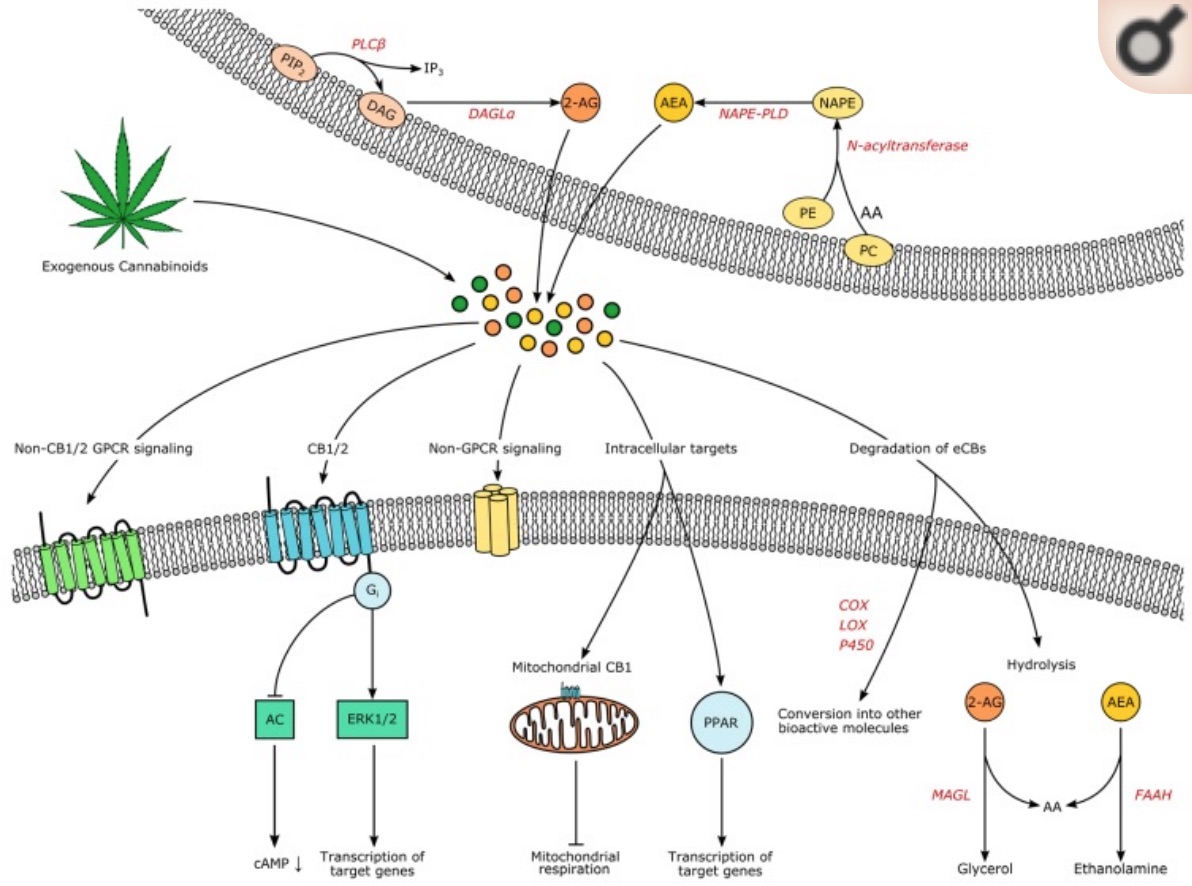

The body’s endocannabinoid system consists of two parts:

- the receptors for cannabinoids

- the substances that bind to those receptors (the agonists)

Activating the cannabinoid receptors causes the passing of signals that control different systems in the body.

Think of this as a general pathway of activating things (rather than a system for getting high).

The endocannabinoid system involves a variety of your body’s processes, including:

- regulating appetite, food intake, and eating behavior

- modulating immune system functions

- managing pain

A hyperactive endocannabinoid system has been shown to be one cause of obesity by many researchers.[ref][ref]

Researchers divide the causes of obesity into several categories: appetite regulation, creation of fat cells, and energy balance. The endocannabinoid system seems to impact appetite regulation by increasing the dopamine reward from food.[ref]

Understanding your genetic susceptibility to gaining weight lies can help you target the right system for weight loss. Genetic variants in the endocannabinoid system are strongly linked to an increased risk of obesity. For people who carry these variants, targeting this system may be very effective for weight loss.

Background info on the cannabinoid receptors:

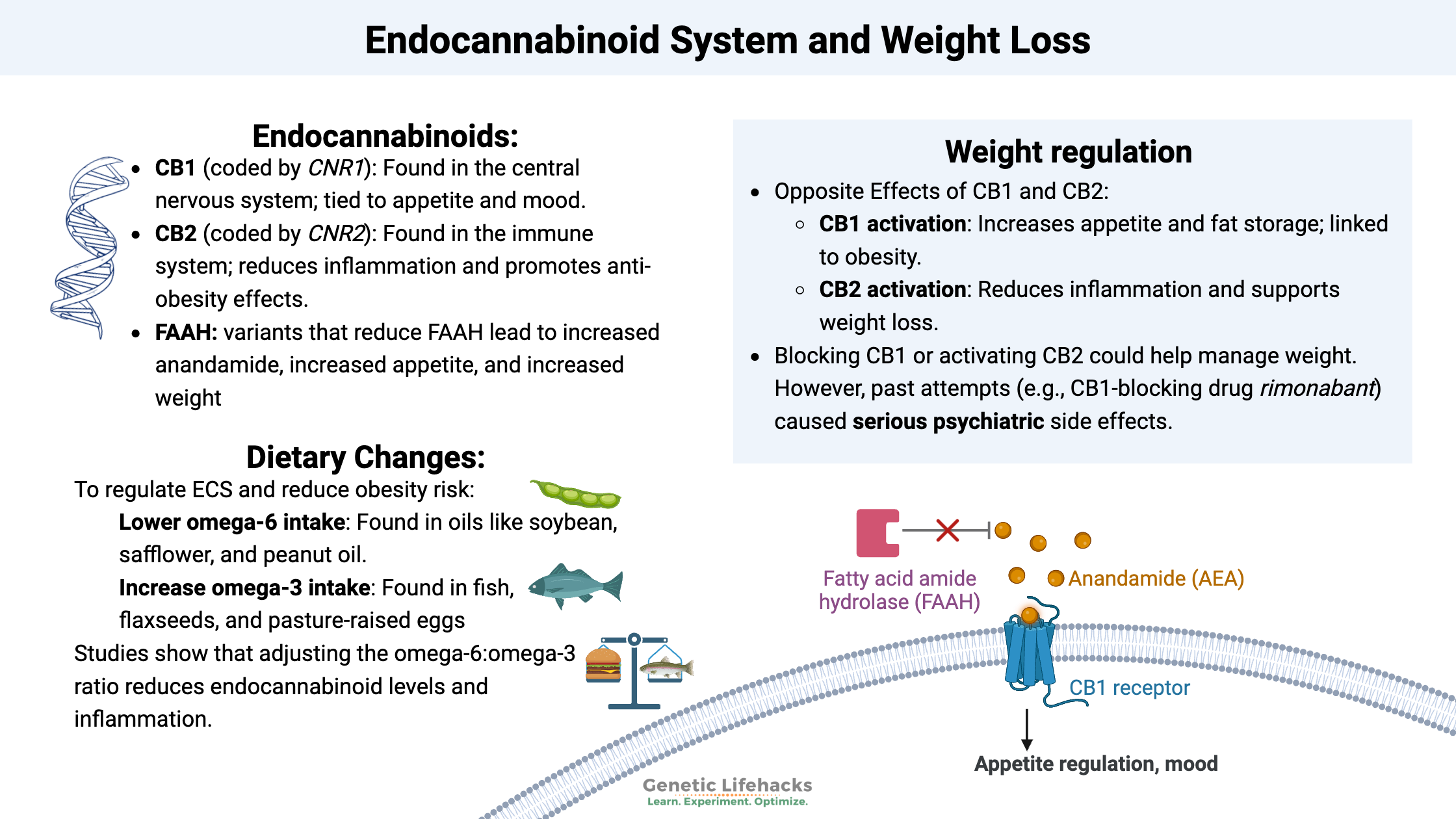

The two main cannabinoid receptors in humans are cannabinoid receptors 1 and 2 – CB1 and CB2.

CB1 (cannabinoid receptor 1) is coded for by the gene CNR1, and CB2 is coded for by CNR2. There are several common genetic variants that alter a person’s cannabinoid receptor levels. Yes, this drives a person’s response to marijuana, but it also makes us unique in our response to pain, appetite, and immune function.

The CB1 receptor is abundantly found in the central nervous system, where it acts on the nerve endings in the GABAnergic system.[ref]

The peripheral receptor for cannabinoids is the CB2 receptor. Its role is mainly in modulating the immune system and controlling inflammation.[ref]

The endocannabinoids that bind to the CB1 and CB2 receptors:

The CB1 and CB2 receptors have endogenous agonists, which is to say that they are substances made in the body that activate receptors.

Anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) are the two main agonists produced by the body.

Anandamide, a fatty-acid neurotransmitter, is made from arachidonic acid, which we get in our diet from omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA).

- Anandamide acts on the CB1 receptors in the central nervous system and on the CB2 receptors, mainly in the peripheral nervous system.

- It is also important for implantation of an embryo, and levels of anandamide rise at ovulation.

- When injected into the lab animals’ brains, anandamide gives more pleasure from sweet things.[ref]

The body synthesizes anandamide from arachidonic acid through a variety of pathways. Anandamide doesn’t hang around long, though, and is quickly broken down by the fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) enzyme.

The FAAH enzyme is encoded by the FAAH gene, which, of course, has genetic variants that impact an individual’s levels. Researchers are looking at these variants in conjunction with obesity and drug use.

Slowing the breakdown of anandamide by drugs that inhibit FAAH is something that is being researched for PTSD, chronic pain, anxiety, and other diseases.

It makes sense that increasing the time that anandamide hangs around in the body would mimic some of the positive effects found in medical uses of cannabis. However, none of the human studies looked at the effect on metabolism or weight gain.

Animal studies, though, show what happens when FAAH is inhibited. Mice bred to have decreased FAAH showed increased body weight with the same amount of food as normal mice on a standard diet. The weight increase was even more dramatic on a high-fat diet.[ref][ref]

2-AG (2-arachidonoylglycerol) is the second main agonist for the CB1 and CB2 receptors. It is also formed from arachidonic acid.

Finally, two related compounds, N-oleoylethanolamide (OEA) and N-palmitoylethanolamide (PEA), may also activate the cannabinoid receptors. They are produced at lower levels from the same precursor lipid molecules that anandamide is derived from.[ref]

Opposite effects of CB1 and CB2 on obesity:

A 2008 study in the Journal of Neuroendocrinology nicely summed up the role of the CB1 receptors. It states that the endocannabinoid system is integrated into the control of appetite and food intake. It goes on to explain that visceral obesity (fat around your organs) “seems to be a condition in which an overactivation of the endocannabinoid system occurs”.[ref]

A 2011 study reiterates that the endocannabinoid system regulates appetite, energy expenditure, insulin sensitivity, glucose metabolism, and lipid metabolism. Obesity is tied to either the overproduction of endocannabinoids -OR- the upregulation of the receptor CB1. The study also looks at inflammation in fat cells when stimulated by lipopolysaccharides (endotoxin) and the effects of a CB1 antagonist on reducing the inflammatory response.[ref]

Mice that are bred to have a CB1 receptor deficiency remain lean even when fed a high-fat diet that makes normal mice fat.

How does the CB2 receptor come into this equation? It is thought that stimulating the CB2 receptor “limits inflammation and promotes anti-obesity effects by reducing food intake and weight gain.” The opposite happens when you block the CB2 receptor. Animal studies show that eliminating the CB2 receptor causes fat mass to increase.[ref]

Two types of fat tissues: Brown and white fat

Fat, or adipose tissue, comes in a couple of different types.

White adipose tissue is what we traditionally think of as fat — the white fat accumulation due to overconsumption of calories (e.g., that donut going straight to my thighs).

Brown fat, on the other hand, is a good kind of fat that is thermogenic and active burning fuel. Brown adipose tissue contains a lot more mitochondria, those powerhouses that are using up calories and cranking out the heat.

The third type of fat is beige adipose tissue. This is the intermediate type found when white adipose tissue converts into brown adipose tissue.

People who are naturally lean tend to have more brown fat, and people who are overweight tend to have little or no brown adipose tissue.[ref] (See the UCP1 article for more on genetics here.)

While rimonabant (the discontinued CB1 antagonist drug) caused decreased body temperature and less movement, newer CB1 antagonists that only target peripheral CB1 receptors have been shown to cause white adipose tissue to shift to beige. Similarly, research shows that CB2 agonists can increase beige fat by increasing UCP1.[ref]

Additionally, the chronic elevation of inflammatory cytokines from white adipose tissue causes many of the health issues linked to obesity.[ref] Activating the CB2 receptor may help to decrease the inflammatory response.

Block the CB1 receptor for weight loss?

Blocking the CB1 receptor works well for weight loss, especially for people with CB1 receptor variants. The drug rimonabant blocks the CB1 receptor. It was approved in the EU in 2006 as a prescription diet medication. But, it was never approved by the FDA — and has since been discontinued in the EU.

Side effects with rimonabant were a serious problem for a subset of patients. Negative effects included an increased risk of psychiatric disorders and increased risk of suicide. Not good. Clinical trials for rimonabant showed that it decreased the reward mechanism of food in the brain – but that it also led to anxiety and depression for some people.[ref]

The endocannabinoid system is also involved in the gastrointestinal system. Activation of the CB1 receptors reduces nausea. Additionally, CB1 receptor activation works by inhibiting relaxation of the LES (lower esophageal sphincter) and inhibiting gastric acid secretion.[ref] The opposite side of this is that blocking the CB1 receptors can cause nausea and possibly heartburn.

What about anandamide and 2-AG levels?

OK – so we know that blocking the CB1 receptor or activating the CB2 receptor peripherally may influence appetite, metabolism, and weight.

Does the endogenous production of endocannabinoids, anandamide, and 2-AG make a difference? Some people naturally produce more anandamide and 2-AG than others (yep, genetics).

The answer here seems to be a definite ‘Yes’.

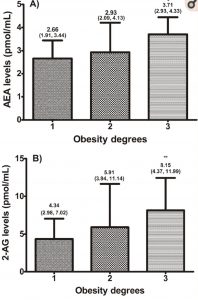

Higher anandamide levels are linked to increased weight. This is also true for 2-AG levels. Not only do anandamide and 2-AG levels increase with obesity (see chart), but the same trend continues with insulin, leptin, and hsCRP, which is a measure of inflammation.[ref]

The fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) enzyme breaks down anandamide and in this way, regulates the levels of anandamide. People with genetic variants that decrease FAAH are, on average, more likely to be overweight or obese.[ref]

The dietary precursor to anandamide comes from linoleic acid, which is an omega-6 fatty acid that is abundant in most people’s diets today. Linoleic acid is very efficiently converted into arachidonic acid, especially with a high ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids in the diet. Arachidonic acid is the precursor for both anandamide and 2-AG.[ref]

Digging a little deeper:

FAAH and anandamide interact with leptin, the hormone that tells the brain to stop eating. Animal studies show that a lack of leptin increases FAAH levels and that giving those animals leptin would reduce FAAH activity.[ref]

In addition to FAAH, the monoglyceride lipase (MGLL) enzyme also can inactivate and break down the endocannabinoids. Monoglyceride lipase mainly acts to control 2-AG levels. The monoglyceride lipase enzyme is encoded by the MGLL gene. Additionally, MGLL is important in triglyceride and cholesterol levels.[ref][ref] (View your MGLL variant in the genetics section)

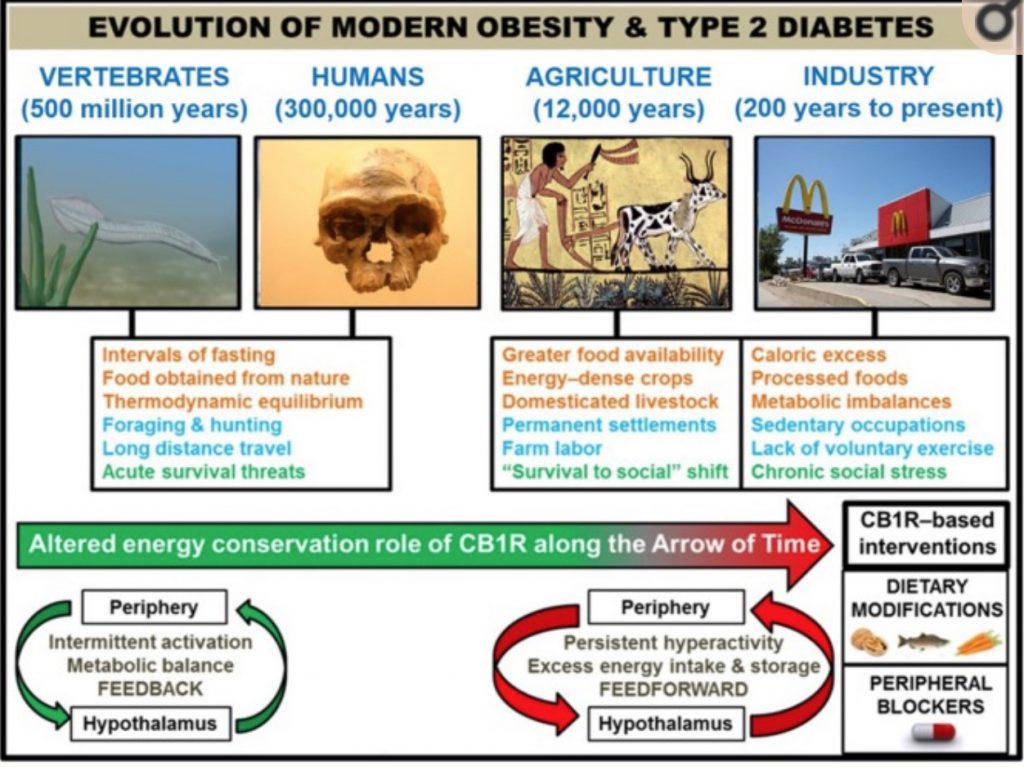

Getting theoretical: Ancestral CB1 was necessary

Some scientists theorize that the CB1 receptor and our endocannabinoids (anandamide and 2-AG) were essential for our ancient ancestors to survive and thrive in a time when food was both scarce and unpalatable. In our modern world with plentiful, hyper-palatable food, the CB1 system driving appetite and energy metabolism is no longer needed.

When you check your genetic variants below, keep in mind that if you carry the variants that increase the risk of obesity, these variants may have been the key to the survival of your ancestors. While you may complain about higher appetite and increased fat mass, those traits drove your ancestors to eat organ meats and fiber-rich vegetables.

Naturally chill, with the munchies…

Imaging stacking together genetic variants that increase the cannabinoid receptors along with higher endocannabinoid levels. This situation is true for a portion of our population, and it impacts both stress resilience and appetite.[ref]

You could almost make an analogy that having higher anandamide levels and more active CB1 receptors leads to someone always being a little bit high with the munchies. The image of a ‘fat and happy’ baby comes to mind as well. While this may not hold true for each individual with this combo of genetic variants, looking at the genetic variants on a population level shows that changes to the endocannabinoid system definitely drive appetite and weight gain for some.

Cannabinoid Genotype Report:

Lifehacks:

Targeting the endocannabinoid system holds a lot of promise for weight loss, but be careful of unintended side effects. As seen by the anti-obesity drug rimonabant, antagonizing the CB1 receptor is effective for decreasing food intake and regulating weight. Keep in mind, though, that the side effects for some people were very serious with respect to increased psychiatric problems and suicide. So take into account your genetics (above) and be aware that CB1 antagonists may affect mood. If you are under the care of a doctor for a mood disorder, please talk with your doctor before making changes that could affect your endocannabinoid system.

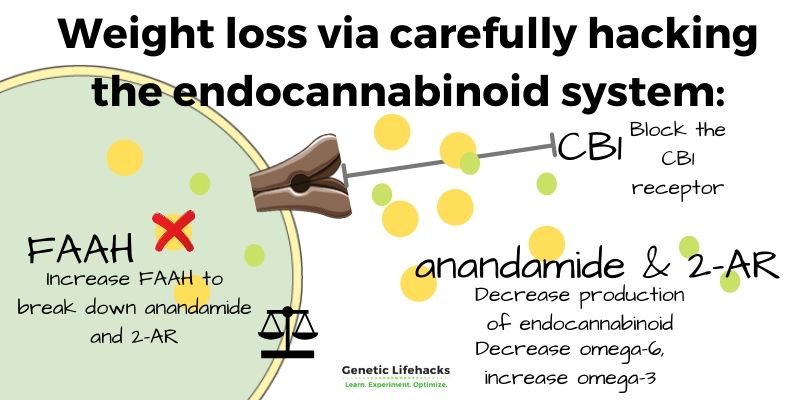

Quick recap:

- appetite and weight theoretically should decrease through blocking the CB1 receptor or through reduced production of the receptor

- decreasing anandamide or 2-AG may also decrease appetite and increase weight loss

- increasing FAAH should decrease anandamide

Dietary changes for altering anandamide & 2-AR:

Related Articles and Topics: