Key Takeaways:

~Niacin (nicotinic acid) is a form of vitamin B.

~Niacin is fortified in flour and cereal and prescribed by cardiologists to lower cholesterol.

~A new study shows that people with genetic variants that increase niacin metabolites are at increased cardiovascular risk with higher niacin intake.

Members will see their genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

Is niacin bad for your heart?

A new study in the journal Nature Medicine shows that higher levels of niacin consumption may increase the risk of heart disease, especially in people with certain genetic variants.

Why is this study important?

In the U.S., cereals and most flour-based foods are fortified with niacin. In addition, for decades, cardiologists prescribed high doses of niacin to lower cholesterol. While niacin is no longer recommended for heart disease prevention because large clinical trials showed that it didn’t reduce risk, some people probably still take niacin because they think it’s good for their hearts.[ref][ref]

A little background on niacin:

Tryptophan is an amino acid that is used in the body in several ways, and one of the ways is to make niacin. Niacin (nicotinic acid) is a form of vitamin B, and when taken in large amounts causes the niacin flush. Niacinamide (nicotinamide) is a niacin derivative that is also available as a supplement.

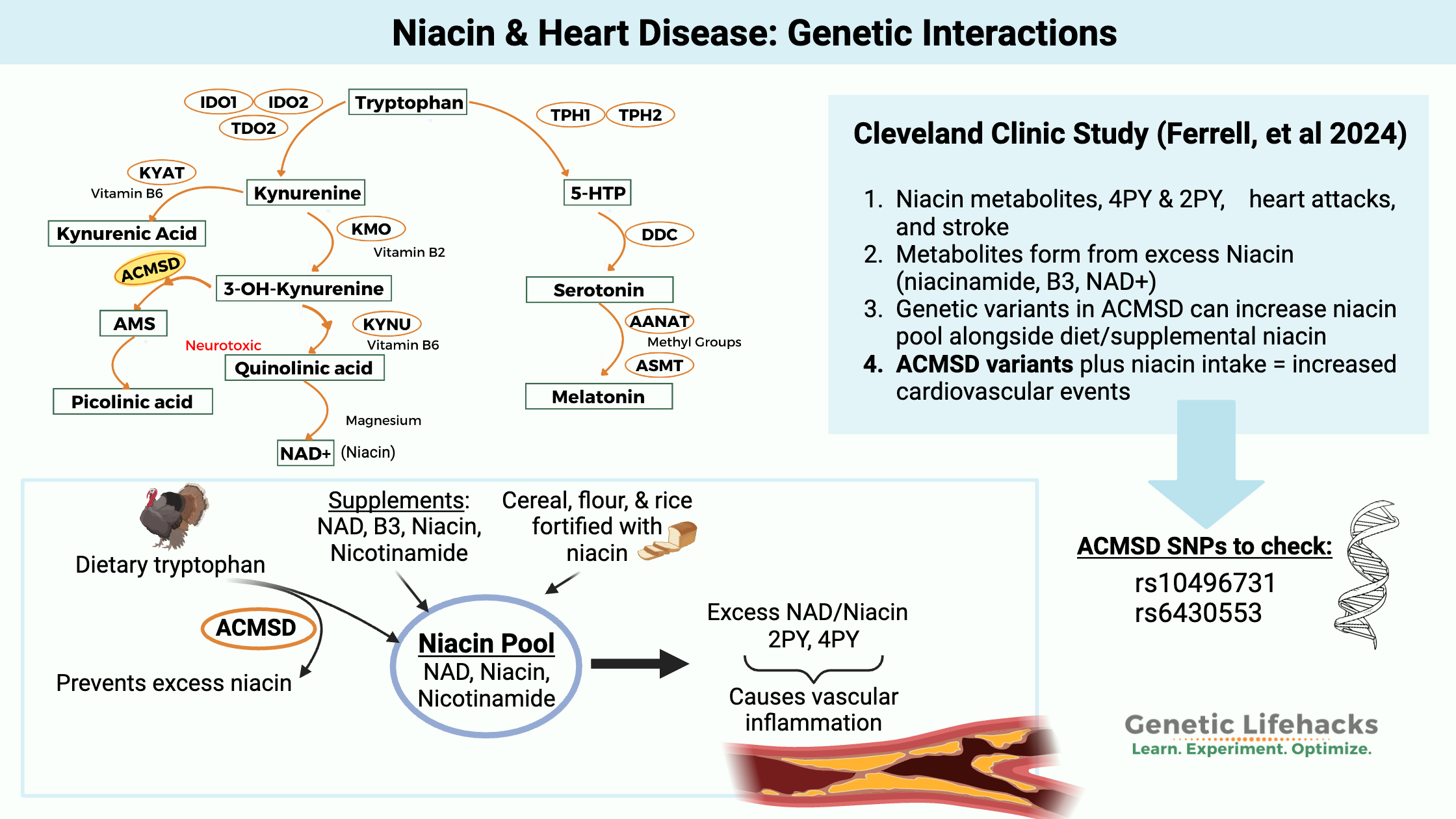

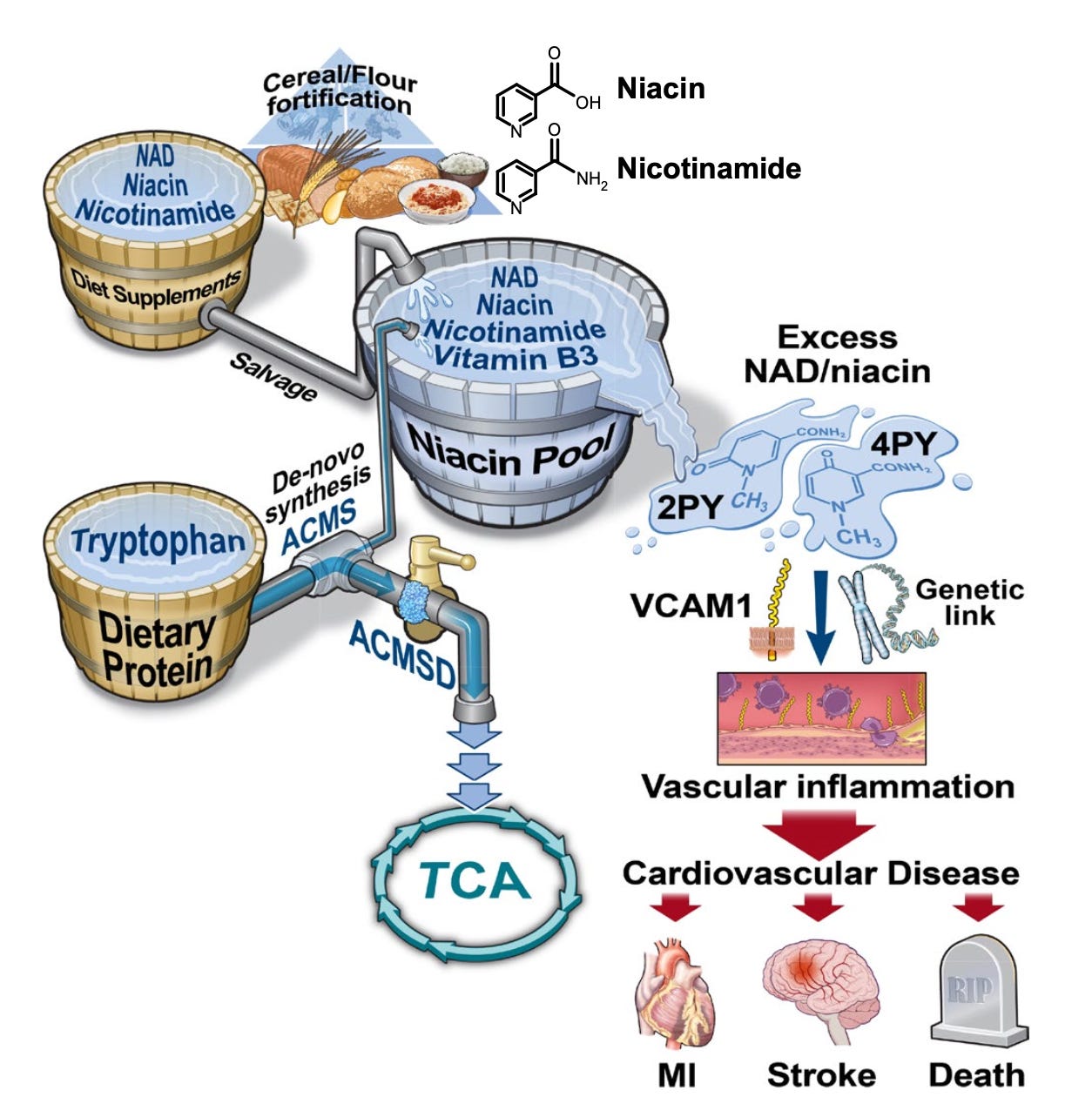

Here’s an image from the study that explains the different inputs from niacin and what happens to them.

A brief overview of the study:

The study was conducted by a team of researchers and physicians at the Cleveland Clinic, which is a top hospital in the US for cardiology.

The study is an untargeted metabalomics study in which the researchers looked at a number of different metabolites in the plasma of stable heart patients to see if there was an association with heart attacks or other cardiovascular events. The study included both US and EU cohorts of several thousand patients.

The researchers found that metabolites related to niacin metabolism were associated with an increased risk of major cardiovascular events (heart attack, stroke, death).

The results showed that circulating levels of 2PY and 4PY, which are metabolites formed from excess niacin, were associated with increased major cardiovascular events. Importantly, some people have genetic variants that increase the niacin metabolites. Thus there is a gene X diet interaction, with high niacin intake combined with genetic susceptibility to increase the risk of major cardiovascular events.

Additionally, the researchers used cell lines and genetically modified animals to determine the causation and mechanism of action.

2PY and 4PY levels:

Niacin is metabolized into several products, including nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), nicotinamide riboside (NR), and methylated forms such as 4PY (N1-methyl-4-pyridone-3-carboxamide) and 2PY (N1-methyl-2-pyridone-5-carboxamide).

Increased Risk of Cardiovascular Events:

Individuals in the highest quartile for circulating levels of 4PY have more than double the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events, but when adjusted for kidney function, the risk increase for 4PY was reduced to about a 65% increase.

Genetic Interaction and Enzyme Involvement:

The ACMSD genetic variants rs10496731 and rs6430553 were identified as being significantly associated with 2PY and 4PY levels. The identified variants are common, with more than half of the population carrying them. Animal studies show that reduction of the ACMSD enzyme leads to increased levels of 2PY and 4PY.[ref] Therefore, it makes sense that variants that reduce ACMSD levels would make more niacin available to be added to the pool that is converted to metabolites such as 2PY and 4PY.

Mendelian Randomization Study Shows No Association:

The researchers also conducted a Mendelian randomization study to see if they could prove causation between the ACMSD gene and heart disease risk. The results showed no direct association.

Inflammatory Mechanisms:

The research suggests that 4PY, but not 2PY, promotes vascular inflammation, which makes sense for the association with cardiovascular events. The study also included both cell and animal research to see what 4PY does to the vascular endothelium (lining of the blood vessels). Increased 4PY was shown to increase the expression of VCAM-1, which promotes the adhesion of white blood cells to the walls of blood vessels, causing inflammation.

Considerations for Niacin Fortification:

Niacin has been included in fortified wheat and rice products for decades. The study authors argue for a reevaluation of niacin fortification policies in light of its potential negative effects on heart disease.

Other studies showing higher intake of niacin is a problem:

A 2024 study in older men divided them up by quartiles of niacin intake and looked at benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Those in the upper 25% of niacin intake had a more than doubled risk of BPH compared to the lowest 25% of niacin intake.[ref]

My thoughts:

I was initially skeptical that a water-soluble B vitamin at levels used for fortifying cereal and flour could increase heart disease mortality. However, this study seems to be really well done. The study included the initial metabolomics patient group, and then the results were tested and replicated in several validation cohorts. Genetic analysis was done to determine that some people were probably more at risk than others, and then animal and cell studies were used to figure out the mechanism of action for the genetic link.

Genotype report: ACMSD Gene and Niacin

The study in Nature Medicine shows a clear association between variants in the ACMSD gene and higher 4PY levels. The results of the study indicate that the genetic variants along with a higher intake of niacin may cause endothelial inflammation, leading to a greater risk of major cardiovascular events.

Lifehacks:

Is niacin a problem for you?

The US RDA is 35 mg/day of niacin for adults. Niacin is included in cereals and enriched flour products, including pasta and bread. Niacin is also found abundantly in beef liver, for which a 3 oz serving will meet your RDA of niacin for the day.

To know your current niacin intake, you can track your niacin intake for a few days to see how much you eat. Cronometer.com is an online food-tracking tool. It includes tons of foods, including common restaurant items, and takes into account the niacin in fortified, packaged foods (cereal, bread, pizza, crackers, etc.). This would give you a good idea of how your current niacin intake compares to the RDA.

Studies on dietary niacin show that higher niacin intake is generally associated with better markers for cardiovascular health. However, those studies aren’t necessarily long-term or looking at genetic interactions.[ref]

The question remains, how much is too much? Hopefully, future studies will give us the answer.

Check your supplements:

If you’re taking a niacin or nicotinamide supplement, check to see how much you’re taking each day. Also, check the label if you’re taking a B complex or multivitamin. Add this to your dietary intake to see how much you are getting in a day.

Linoleic acid:

A study in rats showed that high linoleic acid intake suppressed ACMSD expression.[ref] Linoleic acid is an omega-6 fatty acid found in seed oils such as soybean, safflower, sunflower, and canola. Suppression of ACMSD would allow more tryptophan to convert to niacin, increasing the niacin pool.

Considerations for supplementing with NR or NMN

Related articles: