Key takeaways:

~ Selenium is a trace element, selenium is essential in the right amount and used by selenoproteins.

~ Selenoproteins like glutathione peroxidase protect against oxidative stress.

~ While selenium is essential for immune response and viral resistance, too much or too little selenium increases the risk of metabolic syndrome and prostate cancer.

~ Genetic variants can make someone more susceptible to problems with a selenium-deficient diet.

Selenoproteins: Using selenium in your cells

Selenium is found in certain foods and reflects the amount of selenium found in the soil where the food is grown. Some areas, such as New Zealand, have low-selenium soil and, subsequently, higher levels of selenium deficiency in the population. Other areas, such as certain regions in China, have high selenium levels, which can cause selenium toxicity.[ref]

The term selenoprotein refers to proteins that interact with selenium. The role of these proteins can be broken down as:

- transport of selenium

- antioxidant/redox-related enzymes

- thyroid enzymes

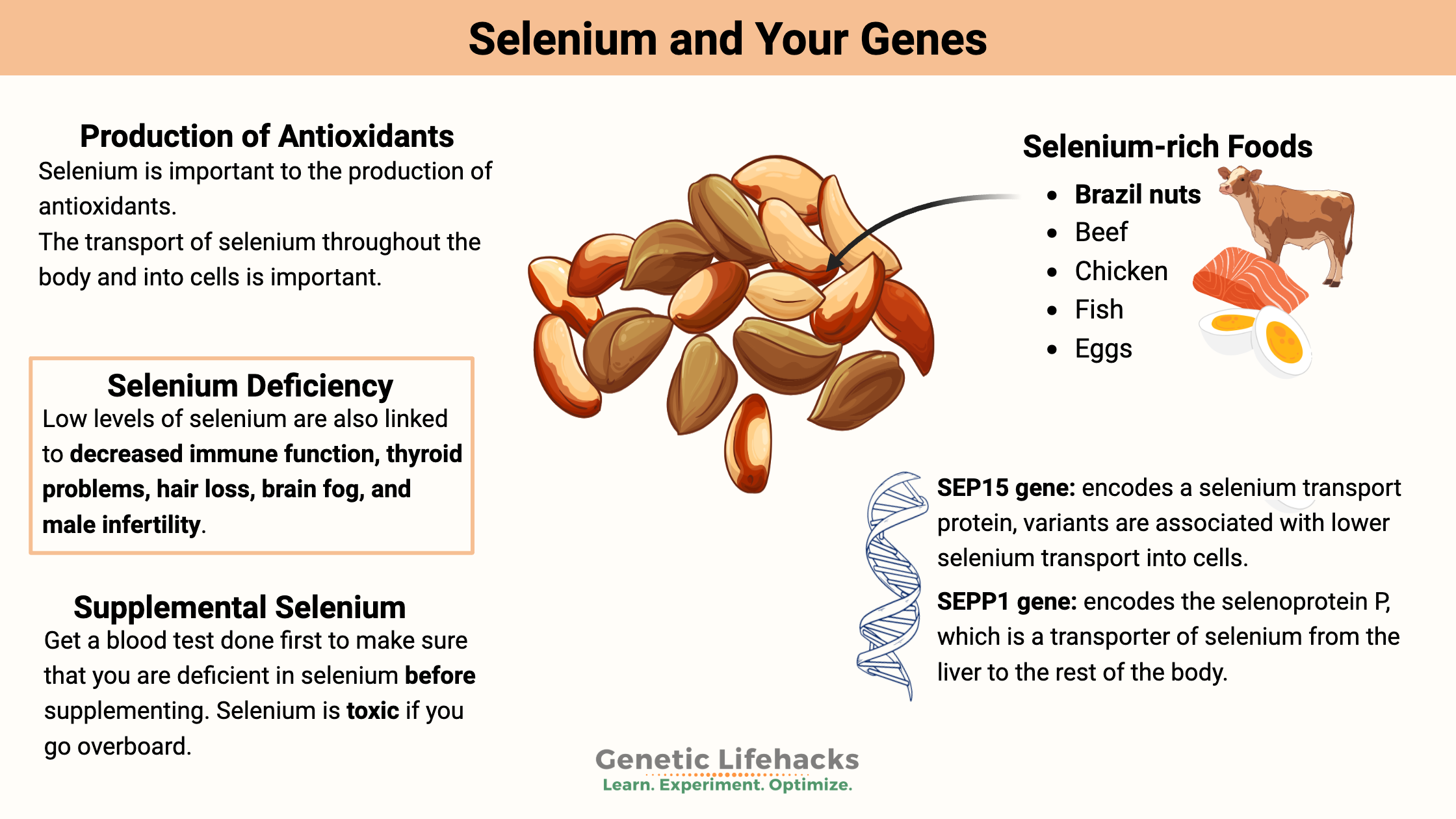

The transport of selenium throughout the body and into cells is important, and it varies a bit due to genetic differences.

The antioxidant usage of selenium is essential for healthy cells. Glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX1) is used in cells to reduce pro-oxidants, such as hydrogen peroxide. Excessive pro-oxidants can cause cell damage or DNA damage.

The glutathione peroxidase 4 (GXP4) protein includes selenium and is essential for reducing lipid oxidation in cells with oxidative stress. This impacts downstream inflammatory processes, including IL-1 and COX2 (cyclooxygenase).[ref]

How much selenium do you need?

The average selenium intake per day in European countries is between 30 – 60 μg/day. The US RDA is 55 μg/day. Other countries have different standards, ranging from 40 – 85μg/day.[ref] Why the wide range? I don’t know…

Getting more than 400 μg/day of selenium can cause toxicity.[ref]

Selenium is essential to the production of antioxidants:

Oxygen is vital to life, but it is also a very reactive molecule. So the body tightly regulates oxidants – producing antioxidant compounds inside your cells to counteract pro-oxidants.

High levels of pro-oxidants, or ROS, cause oxidative stress in cells. This can lead to DNA damage, possibly causing cancerous mutations. It is essential to have the right balance of oxidants in the cell, and selenoproteins are an important part of the balance.[ref]

In general, increasing the intake of selenium has been shown to increase the activity of glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPx1), an important antioxidant.[ref] Don’t go overboard on selenium, though – read the section on toxicity before supplementing.

Selenium deficiency:

Keshan cardiomyopathy is one disease caused by selenium deficiency. This disease causes insufficient cardiac output, resulting in an enlarged heart.[ref]

People with Keshan cardiomyopathy have low selenium concentrations in their blood, causing a lower amount of glutathione peroxidase 1.[ref] Keshan’s disease is named for a region in China where selenium deficiency is very common.

Another disease associated with selenium deficiency is Kashin-Beck disease. The disease causes joint degeneration in children and can cause dwarfism.[ref]

Both of these diseases are thought to result from decreased antioxidants (e.g., glutathione peroxidase) due to low selenium status.

Low levels of selenium are also linked to decreased immune function, thyroid problems, hair loss, brain fog, and male infertility.

Selenium and the immune system:

When the immune system is fighting off a viral infection, a lot of reactive oxygen species (ROS) are formed. ROS is important in fighting off the virus, but when it overwhelms the body’s ability to neutralize it, oxidative stress in the cell results.

Specific viruses that trigger excessive oxidative stress include Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis B, RSV, hepatitis C, Ebola, and HIV.[ref]

More recently, research shows that SARS-CoV-2 also increases ROS and interacts with selenoproteins.[ref] Selenium (along with other vitamins and minerals) is important in the body’s viral response.

Additionally, some viruses interact with the selenoproteins (glutathione peroxidase and thioredoxin reductase), reducing the amount of these proteins. Thus, it can be a double-whammy of needing more antioxidants to deal with ROS and simultaneously having reduced selenoproteins.

Sufficient selenium is also essential for preventing viral replication of certain viruses, such as the coxsackie virus and influenza.[ref]

A recent article in the journal Medical Hypothesis explains that sodium selenite, a specific form of selenium, may help to stop the replication of coronaviruses.[ref]

Selenium and thyroid function:

Thyroid hormones regulate overall metabolism (calories burned), control heartbeat, impact body temperature, increase lung oxygenation, increase the development of muscle fibers, and stimulate bone growth in metabolism.[ref]

While iodine is perhaps the best-known cofactor micronutrient for the thyroid, selenium is also important.

Selenium is essential for creating the DIO1 and DIO2 enzymes, which convert between the active and storage forms of thyroid hormones.[ref]

Additionally, selenium in the antioxidant system, especially GPX1, is important in protecting against oxidative stress in the thyroid itself. Hashimoto’s, an autoimmune cause of hypothyroidism, is linked to low selenium.[ref]

Related article: Genetics and thyroid function.

Obesity and selenium status:

Several studies have shown that low selenium status is often found in people with higher BMI. For example, a study in Spain found that overweight children were likely to have serum selenium levels that are 14% lower than normal-weight children. Not all studies agree, though, and there are likely other factors at play also (such as thyroid function).[ref]

More is not always better!

When it comes to selenium, more is not better. Instead, having selenium levels in the middle of the normal range is usually best.

For example, a study of metabolic syndrome found that people with low and high selenium concentrations were more likely to have metabolic syndrome than those in the middle tiers.[ref]

Similarly, men with low or high selenium levels are at an increased risk of prostate cancer.[ref]

Selenium toxicity: Consuming more than 400 mcg/day of selenium is associated with selenium toxicity. Signs of toxicity include fragile hair, and fingernail problems.

Selenium in food:

The amount of selenium found in foods depends on the type of food and the amount of selenium in the soil. Selenium content of the soil varies worldwide, depending on the pH of the soil, organic matter, soil composition, agricultural activity, and mining.[ref]

Here is the variation in selenium across US states (USGS map):

Plants are the primary source of selenium in foods for humans and animals. Plants bioaccumulate the selenium from the soil as selenium compounds and convert it to organic selenium. For example, plants can convert selenium from the soil into selenocysteine or selenomethionine, which we can absorb and use.

In general, foods that are higher in selenium include Brazil nuts, organ meats such as kidney and liver, cod, salmon, mustard, egg whites, and whole wheat (dependent on soil).[ref]

For animal foods, such as chicken, the selenium content depends on what the animal is eating. For example, selenium is added to poultry feed in some countries.[ref] Judging by the map above, grass-fed beef from the Dakotas or Montana is likely to have more selenium than cattle grazing in New Mexico or Arizona. Most people today eat foods grown in a range of locations, so having a varied diet may help protect them from selenium deficiency.

Selenium Genotype Report

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks for low selenium:

How much selenium do you need?

At a glance:

- RDA: 55 mcg/day (both men and women)

- UL: 400 mcg/day (adults)[ref]

Stop smoking:

Smokers have lower selenium levels because more is needed to counteract the oxidative stress created by cigarette smoke.[ref] Simply put, avoiding cigarette smoke is important if you have low selenium levels. Learn more about breaking down cigarette smoke here.

Eat more selenium-rich foods:[ref]

- Brazil nuts (depending on soil selenium)[ref]

- Beef

- Chicken

- Fish

- Eggs

- Yeast

- Wheat (depending on soil)

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

Thyroid Hormones: Genes, Hypothyroidism, and T4/T3 Conversion

References: