Key takeaways:

~ The thyroid is a master regulator that controls many of your body’s systems including metabolism, body temperature, heart rate, breathing, and body weight.[ref]

~ There are two major forms of thyroid hormone: T4 and T3. T4 is the pro-hormone and T3 is the active hormone that turns on and off other genes throughout the body.

~ Your thyroid-related genes impact how your body converts T4 to T3, regulates TSH levels, and your susceptibility to autoimmune thyroid problems.

Members will see their genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

Thyroid Hormones: Genetic variants, hypothyroidism, and conversion of thyroid hormones

Thyroid hormone levels play a vital role in your overall health and well-being. While people often associate the thyroid with metabolism and weight management, thyroid hormones affect a wide range of bodily functions, including body temperature, gut health, muscle energy, heart rate, skin, bones, and the immune system.

This is important because hypothyroidism is really common. In the U.S., one of the most commonly prescribed drugs is thyroid medication (levothyroxine, Synthroid), with 84 million people taking the drug.[ref] Yet, not everyone has a resolution of symptoms when taking T4-only medications, leaving millions still not feeling their best. And not everyone is properly testing for thyroid issues, leaving many unsure of how well their thyroid is functioning.

Genetic factors account for up to 65% of the differences in thyroid hormone production between healthy individuals, with environmental factors accounting for the rest of the difference.[ref] If you have thyroid problems, learning which genetic variants you carry may shed light on the root cause of your thyroid dysfunction. Understanding your genetic variants can help you — along with your doctor if needed – figure out the best way to solve the problem.

Thyroid hormones influence almost every system in the body, from metabolism and growth to vital functions like body temperature regulation. To fully understand this, let’s lay out some basic definitions and background science about how the thyroid works.

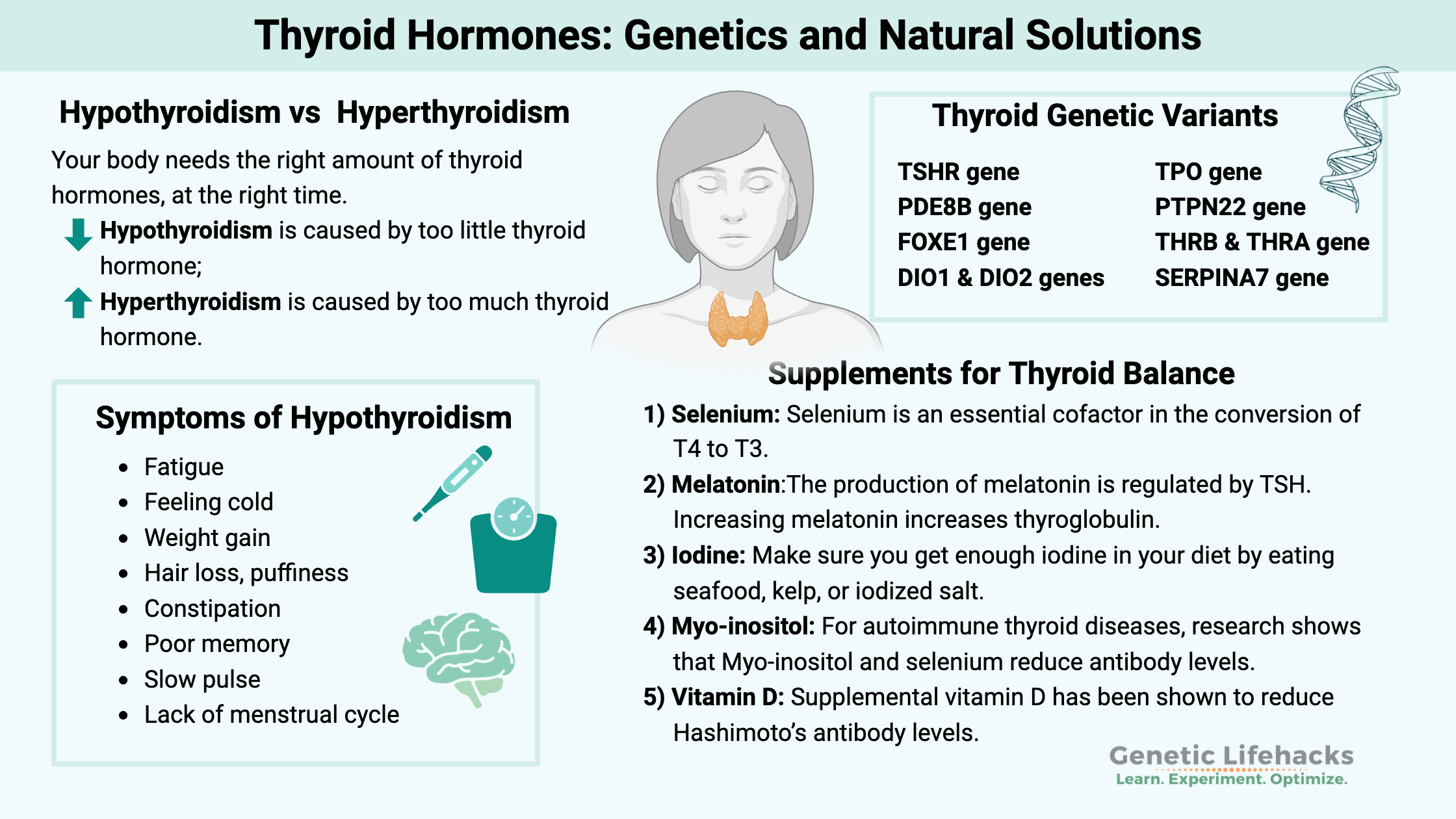

Hypothyroidism vs hyperthyroidism: The need for balance

Your body needs the right amount of thyroid hormones at the right time. Both too much and too little can cause systemic issues. High TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone) levels generally indicate hypothyroidism, while low TSH suggests hyperthyroidism.[ref] (More on better tests in the Lifehacks section.)

| Condition | Cause | Common Symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothyroidism | Too little thyroid | Fatigue, cold intolerance, weight gain, hair loss, constipation, slow pulse |

| Hyperthyroidism | Too much thyroid | Fast heartbeat, heat intolerance, weight loss, nervousness, sweating, insomnia[ref] |

How are thyroid hormones produced?

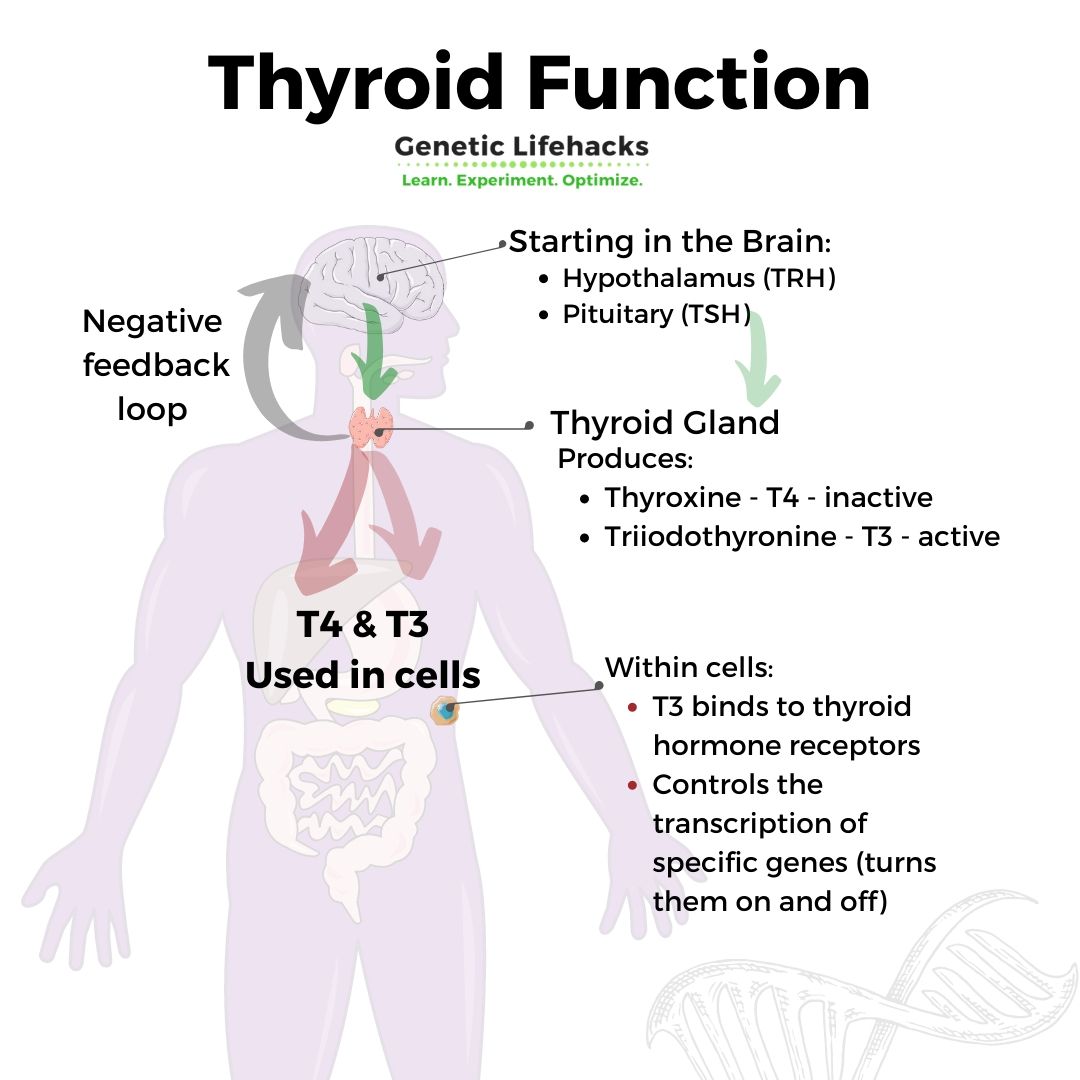

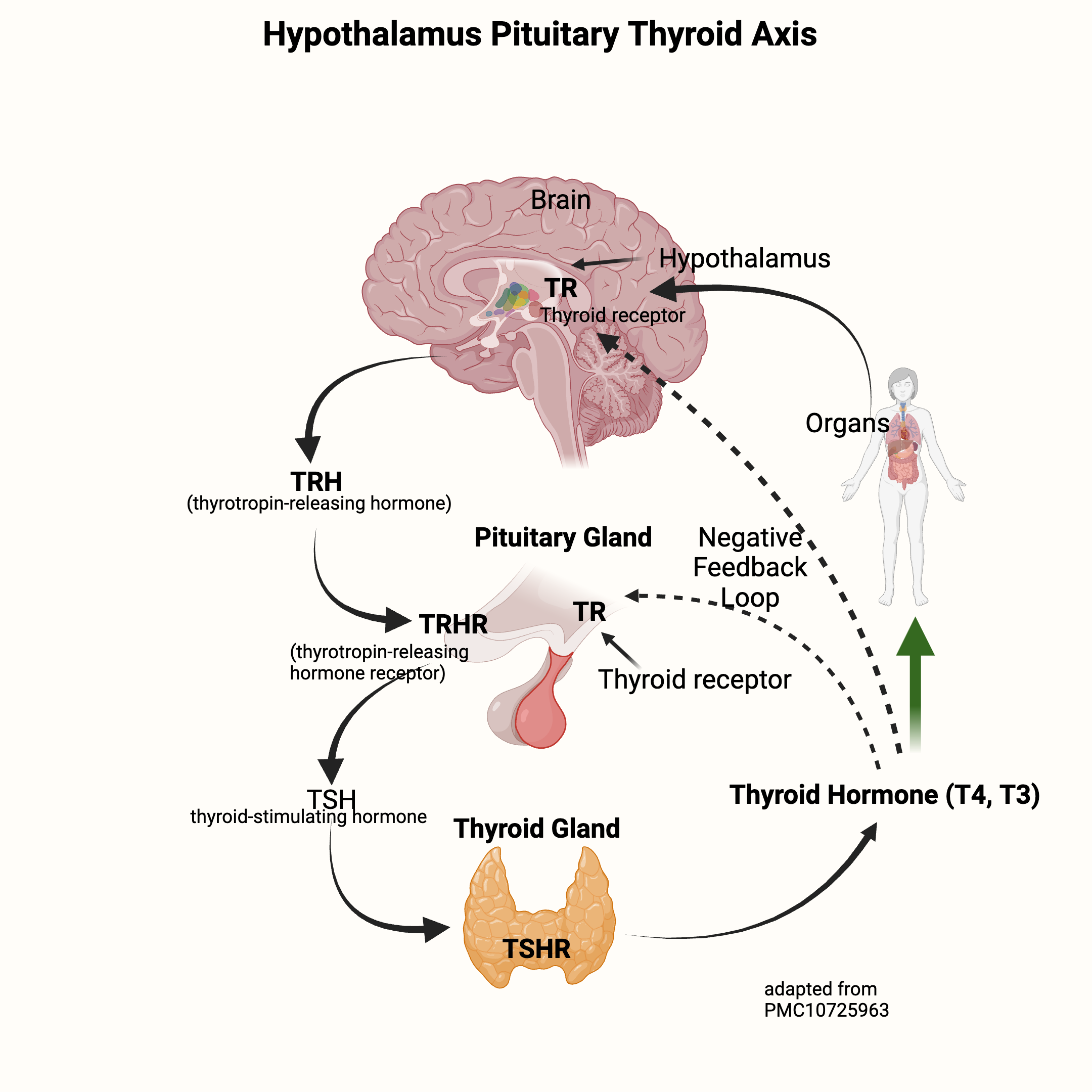

Thyroid hormone production is controlled by the HPT axis (hypothalamus, pituitary, thyroid), a complex feedback loop that regulates and controls the amount of active and inactive thyroid hormone.

The hypothalamus, a region in the brain, and the pituitary gland control the thyroid gland’s rate of producing and releasing thyroid hormone.

- The hypothalamus releases thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), which signals to the pituitary gland.

- The pituitary then creates and releases thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).

- TSH then travels to the thyroid gland to signal for the production of thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3).

T4 and T3 are the two thyroid hormones, with T4 being an inactive form that can be converted to T3. Think of T4 as a stepping stone to T3, which is the star of the show that does all the work.

The circulating T4 and T3 levels are detected by the brain and the pituitary gland, which then work together to increase or decrease TSH to signal for more (or less) thyroid hormone production.

| Hormone | Role | Activity | Where Produced/Converted |

|---|---|---|---|

| T4 | Pro-hormone | Inactive | Thyroid gland |

| T3 | Active hormone | Active | Converted from T4 in liver, thyroid, kidneys, muscles |

What does thyroid hormone do inside a cell?

Essentially, thyroid hormone turns on genes.

Once inside a cell, the thyroid hormone crosses into the nucleus and binds to a thyroid hormone receptor, triggering the transcription of certain genes. These receptors in the cell nucleus are responsible for turning on specific genes so the proteins coded by those genes can be made.[ref]

When thyroid hormone is absent, markers on the nuclear DNA prevent the genes from being transcribed.[ref]

In different cell types, the thyroid hormone receptors (THR) will control the production of different proteins.

- For example, T3 can enter the cell nucleus and bind to the thyroid hormone receptor that controls the liver’s transcription and production of fatty acids, called de novo lipogenesis.

- Thyroid hormone receptors also regulate the creation of mitochondria and the transcription of some genes within the mitochondria.[ref] Mitochondria are responsible for energy production in your cells, so thyroid hormone levels affect cellular energy.[ref]

Going a little deeper:

The thyroid hormone receptors (THR) in the cell nucleus don’t act alone. They often pair with retinoic acid receptors (activated by vitamin A) and rely on adequate levels of zinc for proper binding to DNA. This makes it important to have adequate vitamin A and zinc levels, along with producing enough thyroid hormone.[ref]

There are two different thyroid hormone receptors: THR-alpha and THR-beta. While both are located in most types of cells, THR-beta (THRB gene) is the primary form in the liver, and THR-alpha (THRA gene) is the major form in the heart cells and the bones.[ref] All of these genes are included in the genotype report below.

Genetic variants that impact thyroid hormone levels:

Genetic variants can affect:

- TSH levels

- T4-to-T3 conversion (DIO1, DIO2, DIO3 genes)

- Susceptibility to autoimmune thyroid diseases

- Balancing T4 and T3: The Conversion Process

Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) variants:

TSH is released from the pituitary gland and signals the thyroid gland to make T4 and T3. The basic thyroid test most doctors run is to check the TSH level. According to the Cleveland Clinic, normal TSH levels for adults are 0.27 – 4.2 uIU/mL. Higher TSH levels indicate hypothyroidism, while very low TSH levels can indicate hyperthyroidism.

Genetic variants in the TSH-related genes are responsible for approximately 50 – 90% of thyroid hormone variability, meaning some people have naturally higher or lower TSH levels. This may influence TSH test results.[ref] Of note here, measuring TSH levels gives a general sense of how much of a signal is being sent to the thyroid gland, but it isn’t actually measuring how much T4 or T3 is being produced.

T4 and T3:

The thyroid gland produces and releases about 4x more T4 (inactive form) than T3 (active form). T4 gets converted to T3 when it is needed in your cells.

The balance of T4 and T3 is extremely important, and there are multiple systems in place to regulate it.

T4 and T3 circulate either bound to proteins (>99%) or in a free state (less than 0.05%). T4 is the primary circulating thyroid hormone (about 80% is T4), and it is an inactive form of thyroid hormone. T4 can be activated into the active T3 hormone by enzymes (DIO1, DIO2) made in the liver, thyroid, kidneys, or muscles. About 80% of T3 is produced from T4 using the DIO enzymes.[ref]

The circulating T3 level then controls the release of more TSH from the hypothalamus and pituitary. This is a negative feedback loop that is highly sensitive to changes in thyroid hormone levels. If T4 levels drop, there is an immediate increase in the secretion of TRH and TSH. As T3 levels increase, the secretion of TRH stops.[ref]

Here’s a graphic to explain the release of TRH (thyrotropin-releasing hormone) from the brain, which stimulates TSH to be released from the pituitary. TSH then travels to the thyroid gland to stimulate T4 and T3 production — which feeds back to the brain to shut off TRH and TSH production.

Variants in the deiodinase genes (DIO1, DIO2, and DIO3) affect how well T4 converts to T3.

Converting T4 to T3: Genetic variants impact active thyroid levels

Thyroid hormone levels are an intricate balance between the production of T4, conversion to T3, inactivation to rT3, balance of TSH levels, and the feedback loops controlling TRH and TSH. For example, T3 levels are strongly regulated by a feedback loop. Too much active T3 in cells will cause enzymes to inactivate the T3 into reverse T3 (rT3).[ref]

The deiodinase enzymes, DIO1-3, catalyze the conversion of thyroid hormone. Understanding your genetic variants in DIO1 and DIO2 can be very helpful for people who don’t respond well to T4-only medications like levothyroxine.

| Enzyme | Gene | Function | Main Sites of Action | Cofactors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIO1 | DIO1 | Converts T4 to T3, degrades T3/T4 | Liver, kidney, thyroid, pituitary | Iodine, selenium |

| DIO2 | DIO2 | Converts T4 to T3 | Muscles, CNS, pituitary, thyroid, heart | Selenium |

| DIO3 | DIO3 | Inactivates T4/T3 (to rT4/rT3) | Skin, brain, heart |

DIO1:

The deiodinase 1 (DIO1) gene encodes a protein that converts T4 (inactive pro-hormone) to T3 (active hormone). The enzyme is involved in the degradation of both T3 and T4 in the liver, kidney, thyroid, and pituitary gland, which control overall hormone levels. Both iodine and selenium are cofactors in these reactions.[ref]

DIO2:

DIO2 (deiodinase 2) is also involved in converting T4 to T3, mainly in the skeletal muscles, central nervous system, pituitary, thyroid, heart, and brown adipose tissue.[ref]

Researchers think that hypothyroid individuals with DIO2 polymorphisms may benefit from a combination of T4 and T3 hormone medications.[ref] More on this in the Lifehacks section.

DIO3:

The third deiodinase enzyme is DIO3, which inactivates both T4 and T3. DIO3 converts T4 to rT4 (reverse T4) and T3 to rT3 (reverse T3). This is an important regulatory mechanism to prevent too much T3 activity.

DIO3 is active primarily in the skin and in the prefrontal cortex region of the brain. Recent research also points to DIO3 playing a role in the functioning of the heart. The heart muscle uses a lot of energy, and thyroid hormone is important in the way cardiomyocytes produce energy. When DIO3 activity increases in the heart, it reduces the availability of T3, which can negatively impact heart function. [ref]

DIO3 also plays an essential role during the development of the nervous system of a fetus. In adults, DIO3 is still found in certain regions of the brain and regulates thyroid hormone activity there. The DIO3 gene is very sensitive to epigenetic factors, such as exposure to environmental endocrine disruptors.[ref]

Iodine plays an essential role in thyroid hormone:

Iodine molecules are an essential part of the T4 and T3 hormones. The “4” in T4 represents four iodine molecules, and “3” in T3 indicates three iodine molecules. The thyroid gland has specific transporters to move iodide into cells, where the T3 and T4 are produced. More on these transporters in the genetics section below.

Thyroid and other hormones: Interactions with progesterone, estrogen, and cortisol

T4 and T3 hormone levels are influenced by and interact with other hormones, including estrogen, testosterone, and progesterone.

| Factor | Effect on Thyroid Function |

|---|---|

| Estrogen | Increases T4/T3 in hyperthyroidism, decreases in hypothyroidism |

| Progesterone | Can elevate free T4, decrease free T3 |

| Cortisol | High levels increase TSH, decrease thyroid hormone |

| Environmental | Endocrine disruptors can bind thyroid hormone proteins |

Estrogen:

In women who are hypothyroid, there is generally a decrease in E2 (estradiol) levels, and in hyperthyroidism, there is an increase in E2. Cell studies show that T3 enhances the proliferative effect of E2 (estradiol) in breast cancer cells. In healthy women, the fluctuating estrogen levels during the menstrual cycle also naturally influence T4 and T3 levels. E2 is thought to directly act on thyroid cell levels and influence thyroid hormone production. One study notes that the use of estrogen in hormone replacement therapy increases the body’s demand for levothyroxine (synthetic T4) in women who are hypothyroid. [ref]

Progesterone:

Progesterone has been shown to interact with thyroid hormone in multiple ways. Progesterone drugs, which are used for contraception, pregnancy maintenance, or hormone replacement therapy, have been shown to elevate free T4 levels and decrease free T3 levels by suppression of DIO1 and DIO2. [ref]

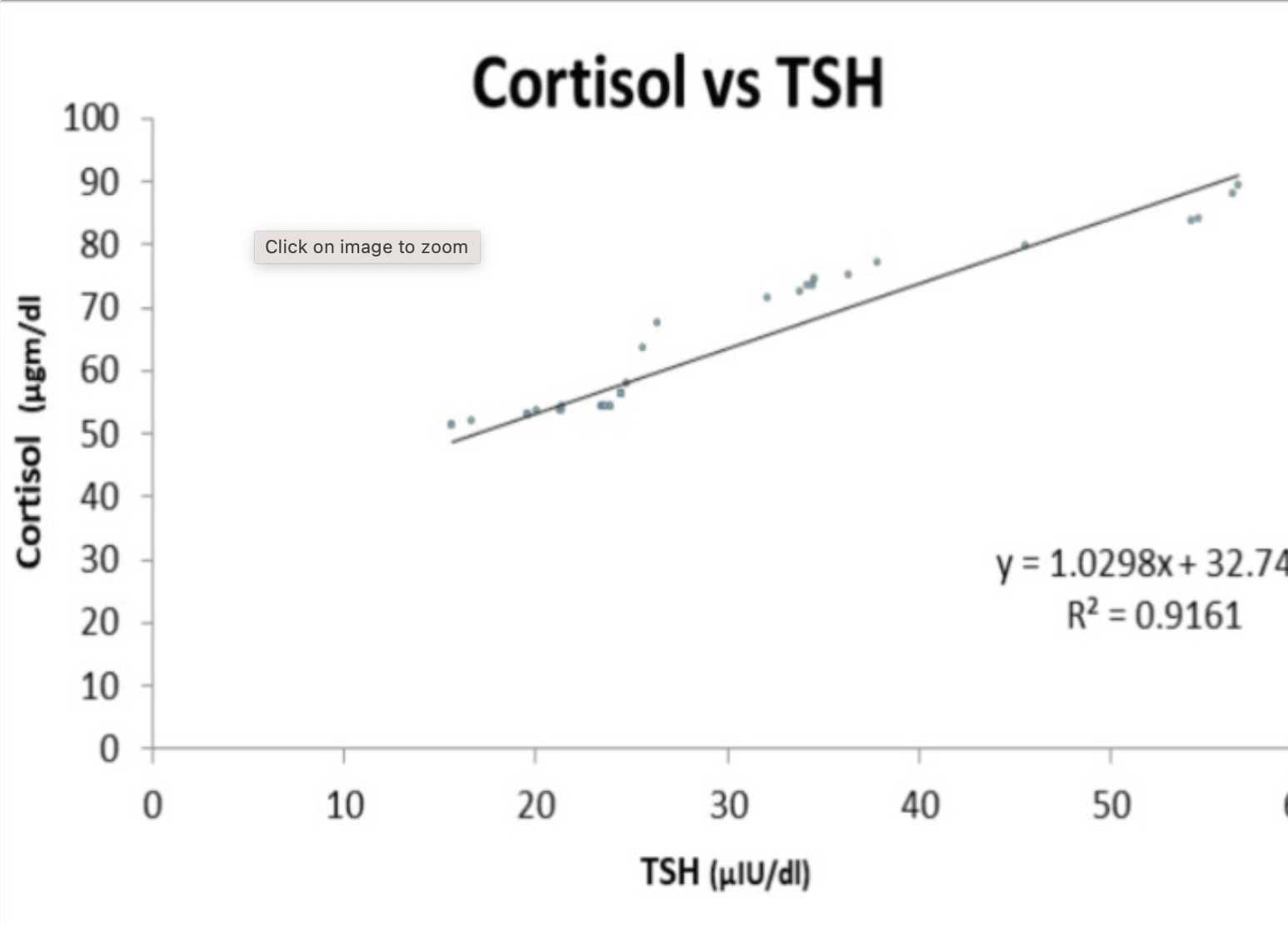

Cortisol:

Cortisol is a stress hormone released by the adrenal glands. In general, high cortisol causes decreased thyroid hormone levels. A study in adults showed that there was a significant correlation between cortisol levels and thyroid hormone levels. The results showed that as cortisol levels go up, TSH levels rise. Patients with severe hypothyroidism had higher cortisol concentrations. Research points to this possibly being bidirectional – higher TSH increasing cortisol and/or higher cortisol increasing TSH.[ref]

Here’s the linear relationship seen in the study:

Relationship of thyroid hormone to cholesterol:

Cholesterol is used by the body to make steroid hormones, including progesterone, estrogen, and testosterone. Hypothyroidism is associated with an increased risk of elevated LDL cholesterol.

Rare mutations in one of the thyroid hormone receptors, THRB, are linked to resistance to thyroid hormone. While thyroid hormone levels are normal or high, the signal isn’t received due to the mutation in the thyroid hormone receptor beta. This presents in some cases as hypercholesterolemia, often with goiter and tachycardia.[ref]

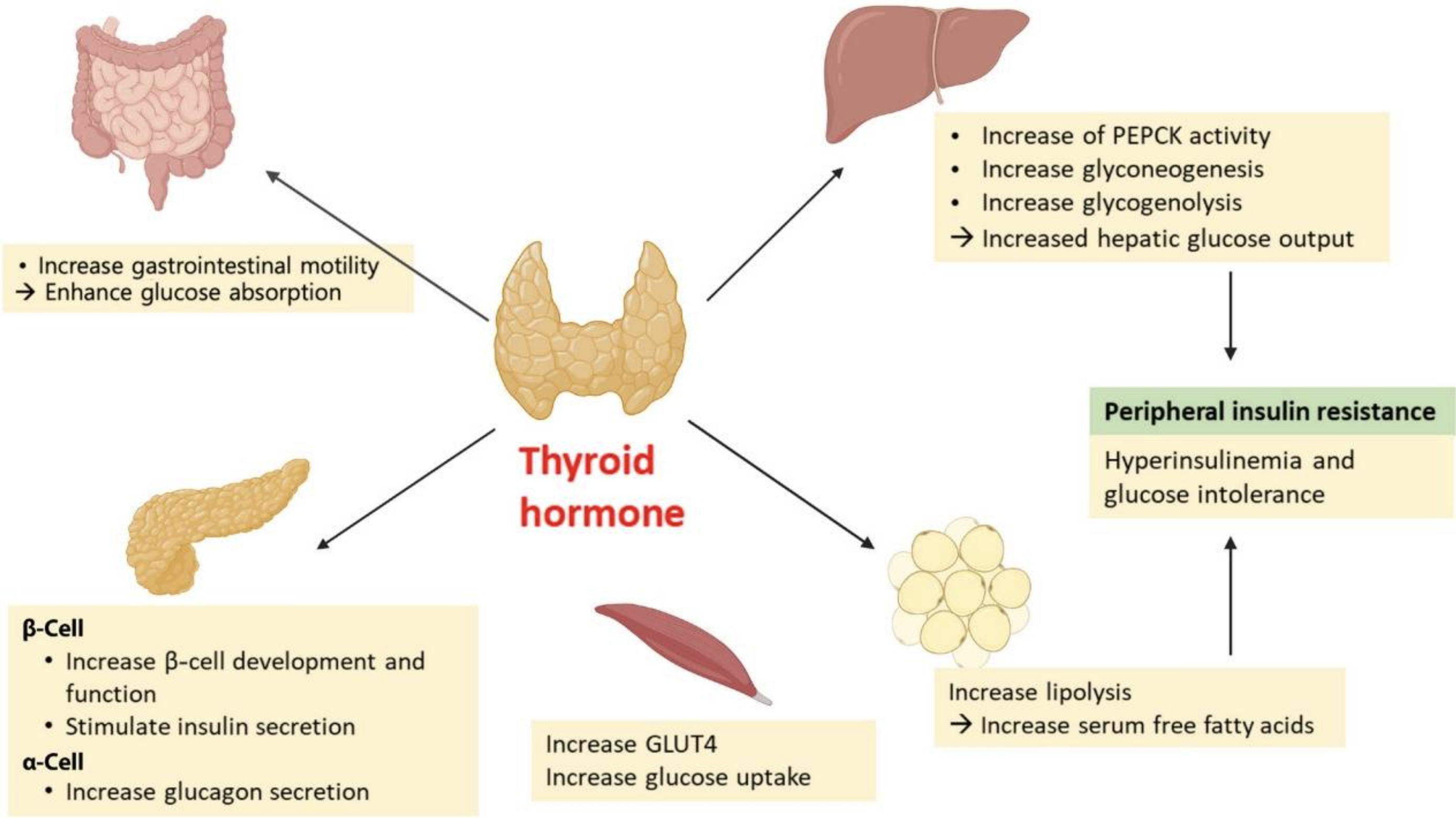

Glucose metabolism and thyroid hormone

Blood glucose levels are tightly regulated by the uptake of glucose into cells. Insulin is the pancreatic hormone that facilitates glucose moving into cells, as well as promoting the storage of glucose as glycogen in the liver.

Thyroid hormone levels have long been known to interact with glucose metabolism and overall metabolic health. T3 interacts with pancreatic beta-cells to promote survival and proper function. T3 also acts in the gastrointestinal tract to enhance glucose absorption and increase gastrointestinal mobility, and in the liver, it promotes gluconeogenesis by increasing the transcription of the GLUT2 (glucose) transporter. [ref]

In type 1 diabetes, there is destruction of the pancreatic beta cells by the immune system. Up to 30% of people with type 1 diabetes also have autoimmune thyroid disorders (Hashimoto’s or Graves’ disease), but the symptoms are sometimes hard to differentiate from the effects of diabetes.[ref]

In the liver, Liver X receptors are activated by thyroid hormone and control the activation of fat tissue. With less liver X receptor beta activation, more T3 remains in the system and drives the browning of white adipose tissue. Brown adipose tissue is more metabolically active, producing heat, and is linked with being less likely to be obese. [ref]

Environmental Influences: Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals and Thyroid Function

I mentioned above that more than 99% of the T4 and T3 that circulate in the plasma are bound to proteins, which are called thyroid hormone binding proteins.

Thyroid hormone binding proteins in the blood include thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG), transthyretin (TTR), and albumin.

The protein-bound T4 and T3 act as a buffer. They are quickly available when more thyroid hormone is needed, and thyroid binding proteins are always available to bind thyroid hormone if it is too high.

Environmental chemicals that are generally classified as endocrine disruptors have structures similar to thyroid hormone, which allows them to bind to the thyroid hormone binding proteins in the plasma. Specifically, research shows that polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dibenzo-p-dioxins, dibenzofurans, and brominated flame retardants such as polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), pentabromophenol (PBP), and tetrabromobisphenol A can all disrupt and interfere with thyroid hormone binding proteins.

While in vitro research studies show that these endocrine-disrupting chemicals could significantly change thyroid hormone levels, in vivo studies show that most people have enough thyroid hormone binding proteins to handle typical environmental exposures to these chemicals.[ref]

Phthalates and BPA are found in plastics, vinyls, processed foods, artificial fragrances, shampoo, lotions, etc.[ref]

- Higher phthalate exposure is associated with lower free T3 and higher TBG.

- BPA levels are associated with decreased total T3 and increased total T4.

Causes of hypothyroidism:

I mentioned above that Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is an autoimmune cause of hypothyroidism, but that is just one reason for reduced thyroid function.

| Cause | Notes |

|---|---|

| Hashimoto’s thyroiditis | Autoimmune, most common in US |

| Viral/postpartum thyroiditis | Often transient |

| Medications (e.g., amiodarone) | Can reduce thyroid hormone production |

| Dietary factors (e.g. iodine deficiency) | Affects hormone synthesis |

| Environmental factors (phthalates, BPA, bromines) | Affects T3 and T4 levels |

Hypothyroidism is most often caused by inflammation of the thyroid gland, called thyroiditis. This can be a transient inflammation, such as due to a viral infection, or it can be more permanent. Postpartum thyroiditis can occur after having a baby when antibodies formed against fetal thyroid cells accumulate and cause an immune response in the mother’s thyroid gland.[ref]

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is the most common cause of hypothyroidism in the US, and it is driven by autoantibodies against thyroid cells. Most research points towards a viral infection, such as a cold or other respiratory infection, as the key trigger of Hashimoto’s. The immune system then causes chronic inflammation in the thyroid gland. Herpes simplex virus, HHV-6, and Epstein-Barr virus are likely causes of Hashimoto’s.[ref][ref][ref][ref]

Prescription drugs can also cause hypothyroidism. Amiodarone is a medication for heart arrhythmia that has a common side effect of hypothyroidism. High-dose lithium carbonate, often prescribed for bipolar disorder, decreases the secretion of thyroid hormone. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors are another class of drugs that can cause hypothyroidism.[ref] If you’re on medications, check for hypothyroidism as a possible side effect.

Let’s switch gears and look at how specific genetic variants could affect YOUR thyroid levels.

Thyroid Hormone Level Genotype Report:

Genetic variants influence your natural thyroid hormone levels as well as your susceptibility to autoimmune thyroid diseases. Here we will look at the genetic variants for the TSH receptor, TSH production, T4 to T3 conversion, the thyroid hormone receptors, and autoimmune susceptibility.

Lifehacks for thyroid problems:

Thyroid hormone testing:

Testing is the only way to know what is really going on with your thyroid hormone levels.

| TSH | Pituitary signal to thyroid | High = hypothyroid, Low = hyperthyroid |

| T4/T3 | Total circulating hormone | Low T4 + high TSH = hypothyroid |

| Free T4/T3 | Unbound, active hormone | High free T3 = hyperthyroidism |

| rT3/rT4 | Inactive forms (reverse T3/T4) | High rT3 may indicate conversion issue |

| Antibody | Autoimmune activity (Hashimoto’s/Graves) | Positive = autoimmune thyroid disease TPO antibodies – Hashimoto’s |

TSH:

The most common test offered by doctors for thyroid function is a TSH test. This test will measure your TSH levels – the signal being sent from the pituitary to the thyroid to increase T4 production. High TSH can indicate hypothyroidism, while low TSH can indicate hyperthyroidism.[ref]

T4:

You can also get a T4 and T3 test, which measures the circulating levels of T4 and T3. This doesn’t tell you a whole lot, though, since they are bound to proteins and not active. A low T4, along with high TSH, is often used to determine hypothyroidism.

Free T4 (fT4) and free T3 (fT3):

Testing free T4 and free T3 gives you the amount of unbound thyroid hormones available in your serum. A high free T3 level is often used to determine hyperthyroidism.

Reverse T4 and reverse T3:

Also available are rT3 and rT4 tests, which can show if you have too much of your free T3 being converted to reverse T3 (inactivated). This may show where the problem lies if you don’t feel better with T4-only medications.

Thyroid antibodies test:

Antibody tests are also available for determining autoimmune thyroid disorders. TPO antibodies can indicate Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. For Graves’, doctors will look at antibodies to the thyroid hormone receptors.

There’s a long list of testing options with normal and optimal values on the Stop the Thyroid Madness website. If your doctor won’t order the tests that you need, in most states in the U.S., you can order your own blood tests.

Thyroid hormone medication options: Genetic Interactions

For people with clinical or subclinical hypothyroidism, there are several medication options available. Talk with your doctor about prescription options for T4 medications (levothyroxine, Synthroid) or the combination therapy of T4 plus T3 (levothyroxine and liothyronine).

Traditionally, T4-only medications are prescribed when TSH levels are high. Newer research, though, shows that this doesn’t always reduce the symptoms of hypothyroidism for everyone, with up to 20% of people not converting the T4 to T3 appropriately. For these individuals, a combination therapy of T4 plus T3 (either synthetic or natural desiccated thyroid) may work better. [ref — good source to read and discuss with your doctor]

Let me explain a little further: So T4 is converted to T3 in certain tissues, including the brain, by the DIO2 enzyme. In some people with hypothyroidism on T4 only (levothyroxine monotherapy), they will still have symptoms such as impaired cognitive function – brain fog – and feeling tired. This is likely due to the T4 not being converted to T3 in the brain. Research studies show that people with DIO2 genetic variants may still struggle with symptoms of hypothyroidism when using T4 only.[ref]

Talk with your doctor if you have questions about what is right for your individual case, and know that there are options available if you still feel symptoms of hypothyroidism when taking levothyroxine alone.

~ Most people are prescribed T4-only (levothyroxine).

~ Up to 20% may not convert T4 to T3 efficiently due to DIO2 variants.

~ Combination therapy (T4 + T3) may help those with persistent symptoms.

Dietary interactions with thyroid function:

The foods you eat can impact your thyroid function, either increasing or decreasing it. In general, consuming these foods in low amounts isn’t harmful to thyroid function, however, negative thyroid effects may be noticed when consuming large amounts on a regular basis.

| Food/Factor | Effect on Thyroid Function |

|---|---|

| Soy | Isoflavones may inhibit hormone production |

| Brassica veggies | Can reduce iodine uptake in low-iodine diets |

| Cassava | Reduces iodine uptake (risk in high-consumption) |

| Seaweed | Excess iodine can cause hyperthyroidism |

| Sucralose | May increase inactive rT3 |

| Gluten | May affect 5% of people with Hashimoto’s |

| Kaempferol | (Fruits/veggies) Induces DIO2, boosts T3 |

Soy:

Soy has isoflavones that inhibit TPO, which is the enzyme needed for the production of thyroid hormone. Most studies show that high levels of soy hurt thyroid hormone production, but the effect is usually mild and doesn’t cause goiters (enlarged thyroid). However, there may be more of a negative effect in people with hypothyroidism or other thyroid disorders.[ref] Consider how much soy you consume if you have TPO gene variants, and experiment with cutting back on soy to see if there is a positive effect on your thyroid function.

Brassica vegetables:

Brassica vegetables – broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, rutabaga, bok choy, and turnips – also contain compounds that can reduce the uptake of iodine and thus negatively affect thyroid function in people with low iodine consumption.[ref] If you have low iodine intake and subclinical or overt hypothyroidism, consider limiting brassica vegetables until the deficiency is resolved.

Cassava:

In tropical areas where cassava (also called yuca) is a staple food, low thyroid function and goiters are common. This is because cassava also contains compounds that reduce iodine uptake.[ref]

Seaweeds:

Common in some Asian cuisines, the excess consumption of seaweed can cause high iodine levels, which may result in hyperthyroidism. [ref]

Avoiding sucralose with low thyroid function:

Sucralose alters thyroid hormone levels by increasing reverse T3 (inactive) in animal studies.[ref][ref] A case study showed that cutting out sucralose helped restore normal thyroid function in a patient with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.[ref]

Eat your fruits and veggies:

The dietary flavonoid kaempferol, found in apples, onions, leeks, grapes, and other fruits and vegetables, induces DIO2, increasing conversion to T3.[ref]

Gluten may be a problem for some people:

Gluten is often pointed to as a culprit in autoimmune thyroid diseases (Graves and Hashimoto’s). However, a 2003 study showed that only about 5% of patients with autoimmune thyroiditis also had immune reactions to gluten.[ref] While that isn’t a huge percentage, it may be worth trialing a gluten-free diet if you have an autoimmune thyroid disease.

Supplements for thyroid health:

Related Articles and Topics:

Is Inflammation Causing Your Depression and Anxiety? The Science Behind the Link

Oxalates, Kidney Stones, & Joint Pain: Genetic Reasons to Avoid Oxalates

References:

Akçay, Müfide Nuran, and Güngör Akçay. “The Presence of the Antigliadin Antibodies in Autoimmune Thyroid Diseases.” Hepato-Gastroenterology, vol. 50 Suppl 2, Dec. 2003, p. cclxxix–cclxxx.

Ballesteros, Virginia, et al. “Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Thyroid Function in Pregnant Women and Children: A Systematic Review of Epidemiologic Studies.” Environment International, vol. 99, Feb. 2017, pp. 15–28. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.10.015.

Bunevicius, Adomas, et al. “Common Genetic Variations of Deiodinase Genes and Prognosis of Brain Tumor Patients.” Endocrine, vol. 66, no. 3, Dec. 2019, pp. 563–72. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-019-02016-6.

Cao, Xinyuan, et al. “Exposure of Pregnant Mice to Triclosan Impairs Placental Development and Nutrient Transport.” Scientific Reports, vol. 7, Mar. 2017, p. 44803. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44803.

da-Silva, Wagner S., et al. “The Small Polyphenolic Molecule Kaempferol Increases Cellular Energy Expenditure and Thyroid Hormone Activation.” Diabetes, vol. 56, no. 3, Mar. 2007, pp. 767–76. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.2337/db06-1488.

Eriksson, Nicholas, et al. “Novel Associations for Hypothyroidism Include Known Autoimmune Risk Loci.” PLoS ONE, vol. 7, no. 4, Apr. 2012, p. e34442. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0034442.

Fernández, Lara P., et al. “New Insights into FoxE1 Functions: Identification of Direct FoxE1 Targets in Thyroid Cells.” PLoS ONE, vol. 8, no. 5, May 2013, p. e62849. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0062849.

Garcia-Marin, R., et al. “Melatonin in the Thyroid Gland: Regulation by Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone and Role in Thyroglobulin Gene Expression.” Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology: An Official Journal of the Polish Physiological Society, vol. 66, no. 5, Oct. 2015, pp. 643–52.

Gudmundsson, Julius, et al. “Common Variants on 9q22.33 and 14q13.3 Predispose to Thyroid Cancer in European Populations.” Nature Genetics, vol. 41, no. 4, Apr. 2009, pp. 460–64. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.339.

Inoue, Naoya, et al. “Functional Polymorphisms of the Type 1 and Type 2 Iodothyronine Deiodinase Genes in Autoimmune Thyroid Diseases.” Immunological Investigations, vol. 47, no. 5, July 2018, pp. 534–42. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1080/08820139.2018.1458861.

Jorde, Rolf, et al. “The Phosphodiesterase 8B Gene Rs4704397 Is Associated with Thyroid Function, Risk of Myocardial Infarction, and Body Height: The Tromsø Study.” Thyroid: Official Journal of the American Thyroid Association, vol. 24, no. 2, Feb. 2014, pp. 215–22. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2013.0177.

Kampf-Lassin, August, and Brian J. Prendergast. “Photoperiod History-Dependent Responses to Intermediate Day Lengths Engage Hypothalamic Iodothyronine Deiodinase Type III MRNA Expression.” American Journal of Physiology – Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, vol. 304, no. 8, Apr. 2013, pp. R628–35. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00577.2012.

Llop, Sabrina, et al. “Association between Exposure to Organochlorine Compounds and Maternal Thyroid Status: Role of the Iodothyronine Deiodinase 1 Gene.” Environment International, vol. 104, July 2017, pp. 83–90. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.12.013.

—. “Association between Exposure to Organochlorine Compounds and Maternal Thyroid Status: Role of the Iodothyronine Deiodinase 1 Gene.” Environment International, vol. 104, July 2017, pp. 83–90. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.12.013.

—. “Association between Exposure to Organochlorine Compounds and Maternal Thyroid Status: Role of the Iodothyronine Deiodinase 1 Gene.” Environment International, vol. 104, July 2017, pp. 83–90. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.12.013.

—. “Association between Exposure to Organochlorine Compounds and Maternal Thyroid Status: Role of the Iodothyronine Deiodinase 1 Gene.” Environment International, vol. 104, July 2017, pp. 83–90. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.12.013.

Malinowski, Jennifer R., et al. “Genetic Variants Associated with Serum Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) Levels in European Americans and African Americans from the EMERGE Network.” PloS One, vol. 9, no. 12, 2014, p. e111301. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0111301.

NM_001128177.1(THRB):C.1357C>A (p.Pro453Thr) AND Thyroid Hormone Resistance, Generalized, Autosomal Dominant – ClinVar – NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/RCV000013377.22/. Accessed 10 Nov. 2021.

Nordio, Maurizio, and Sabrina Basciani. “Treatment with Myo-Inositol and Selenium Ensures Euthyroidism in Patients with Autoimmune Thyroiditis.” International Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 2017, 2017, p. 2549491. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/2549491.

Pałkowska-Goździk, Ewelina, et al. “Type of Sweet Flavour Carrier Affects Thyroid Axis Activity in Male Rats.” European Journal of Nutrition, vol. 57, no. 2, Mar. 2018, pp. 773–82. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-016-1367-x.

Panicker, Vijay. “Genetics of Thyroid Function and Disease.” The Clinical Biochemist Reviews, vol. 32, no. 4, Nov. 2011, pp. 165–75.

Park, Choonghee, et al. “Associations between Urinary Phthalate Metabolites and Bisphenol A Levels, and Serum Thyroid Hormones among the Korean Adult Population – Korean National Environmental Health Survey (KoNEHS) 2012-2014.” The Science of the Total Environment, vol. 584–585, Apr. 2017, pp. 950–57. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.144.

Płoski, Rafał, et al. “Thyroid Stimulating Hormone Receptor (TSHR) Intron 1 Variants Are Major Risk Factors for Graves’ Disease in Three European Caucasian Cohorts.” PLOS ONE, vol. 5, no. 11, Nov. 2010, p. e15512. PLoS Journals, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0015512.

Qian, Wei, et al. “Association between TSHR Gene Polymorphism and the Risk of Graves’ Disease: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Biomedical Research, vol. 30, no. 6, Nov. 2016, pp. 466–75. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.7555/JBR.30.20140144.

Roef, Greet, et al. “Heredity and Lifestyle in the Determination of Between-Subject Variation in Thyroid Hormone Levels in Euthyroid Men.” European Journal of Endocrinology, vol. 169, no. 6, Dec. 2013, pp. 835–44. eje.bioscientifica.com, https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-13-0265.

Sachmechi, Issac, et al. “Autoimmune Thyroiditis with Hypothyroidism Induced by Sugar Substitutes.” Cureus, vol. 10, no. 9, Sept. 2018. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.3268.

Sinha, Rohit, and Paul M. Yen. “Cellular Action of Thyroid Hormone.” Endotext, edited by Kenneth R. Feingold et al., MDText.com, Inc., 2000. PubMed, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK285568/.

Thyroid Hormone Receptors. http://www.vivo.colostate.edu/hbooks/pathphys/endocrine/thyroid/receptors.html. Accessed 10 Nov. 2021.

“Top-Selling, Top-Prescribed Drugs for 2016.” Medscape, http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/886404. Accessed 10 Nov. 2021.

VCV000009790.1 – ClinVar – NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/9790/. Accessed 10 Nov. 2021.

Wright, Caroline F., et al. “Assessing the Pathogenicity, Penetrance, and Expressivity of Putative Disease-Causing Variants in a Population Setting.” American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 104, no. 2, Feb. 2019, pp. 275–86. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.12.015.