Key takeaways:

~ Myalgic encephalomyelitis, also known as chronic fatigue syndrome or ME/CFS, is a debilitating condition

~ Viral and bacterial infections can cause long-term changes to the way that cells produce energy.

~ There are multiple theories on the cause(s) of ME/CFS including post-infectious viral changes, mitochondrial dysfunction, and immune system dysregulation.

~ Genetic studies show that inflammatory pathways and interferon are likely causal factors.

Chronic fatigue syndrome / myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME/CFS): Causes and Research

ME/CFS is a multi-systemic disease affecting somewhere between 0.1% and 2.5% of the population.[ref] In the US, around 1% of the population is diagnosed with ME/CFS.[ref]

In some parts of the world, it is commonly referred to as myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), while in other areas, such as the US, it is often called chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). I’m going to go with ME/CFS here just for consistency.

The symptoms of ME/CFS include:

- chronic exhaustion (more than tired – difficulty staying upright, feeling ill)

- post-exertional malaise, PEM (inability to recover from activity)

- pain and flu-like symptoms

- cognitive dysfunction (brain fog+)

- a general reduction in the overall quality of life, such as being unable to keep a job or regularly attend school

The majority of people with ME/CFS are unable to work, and about 25% are homebound or bedridden.[ref]

History overview:

You would think that there would be a lot more research and better answers for something that has been defined and talked about since at least the 1930s. At least we’ve moved beyond calling it a psychiatric issue that is just all in the patient’s head… like it was referred to in the ’80s and ’90s.

Interestingly, ME/CFS was known as ‘chronic Epstein-Barr virus syndrome’ in the ’80s, pointing towards one of many possible viral causes.[ref] ME/CFS was derisively called the ‘yuppie flu’ at one point.[ref][ref] Dr. Anthony Fauci, as the head of the NIAID, was strongly criticized for the lack of research focus and funding for ME/CFS for over two decades.[ref]

Links between ME/CFS and viral infections:

For many patients, ME/CFS seems to be triggered by an acute infection, usually viral. One study found that almost two-thirds of ME/CFS patients reported an infection-related onset.[ref]

Not all ME/CFS cases can be traced to an infection, though. An autoimmune component likely exists for some ME/CFS patients. Research shows genetic variants with links to autoimmune diseases also have links to ME/CFS in patients with an initial viral cause.[ref]

Other recent studies point to latent or reactivated Epstein-Barr virus being implicated in a portion of ME/CFS patients. One study found that 24% of chronic fatigue patients had DNA from the Epstein-Barr virus in their plasma, in comparison with only 4% of the control group.[ref] Other studies point to a variety of other possible viral triggers for ME/CFS, including herpes simplex or cytomegalovirus, but not all studies agree.[ref]

Researchers examined brain and spinal cord postmortem tissue samples from ME/CFS patients. They found that HHV-6 (human herpesvirus 6) miRNA was abundant in these tissues. This was in stark contrast to control tissue samples. Additionally, the researchers found active EBV infection in the ME/CFS tissue. Like all herpesviruses, HHV-6 is a latent virus that remains in the body throughout life. HHV-6 integrates into the telomeres of host cell chromosomes.[ref]

Alterations in immune response and cellular energy:

Let’s dive into the studies on how the immune response is altered in ME/CFS patients.

Natural killer cells and impaired calcium channels in ME/CFS:

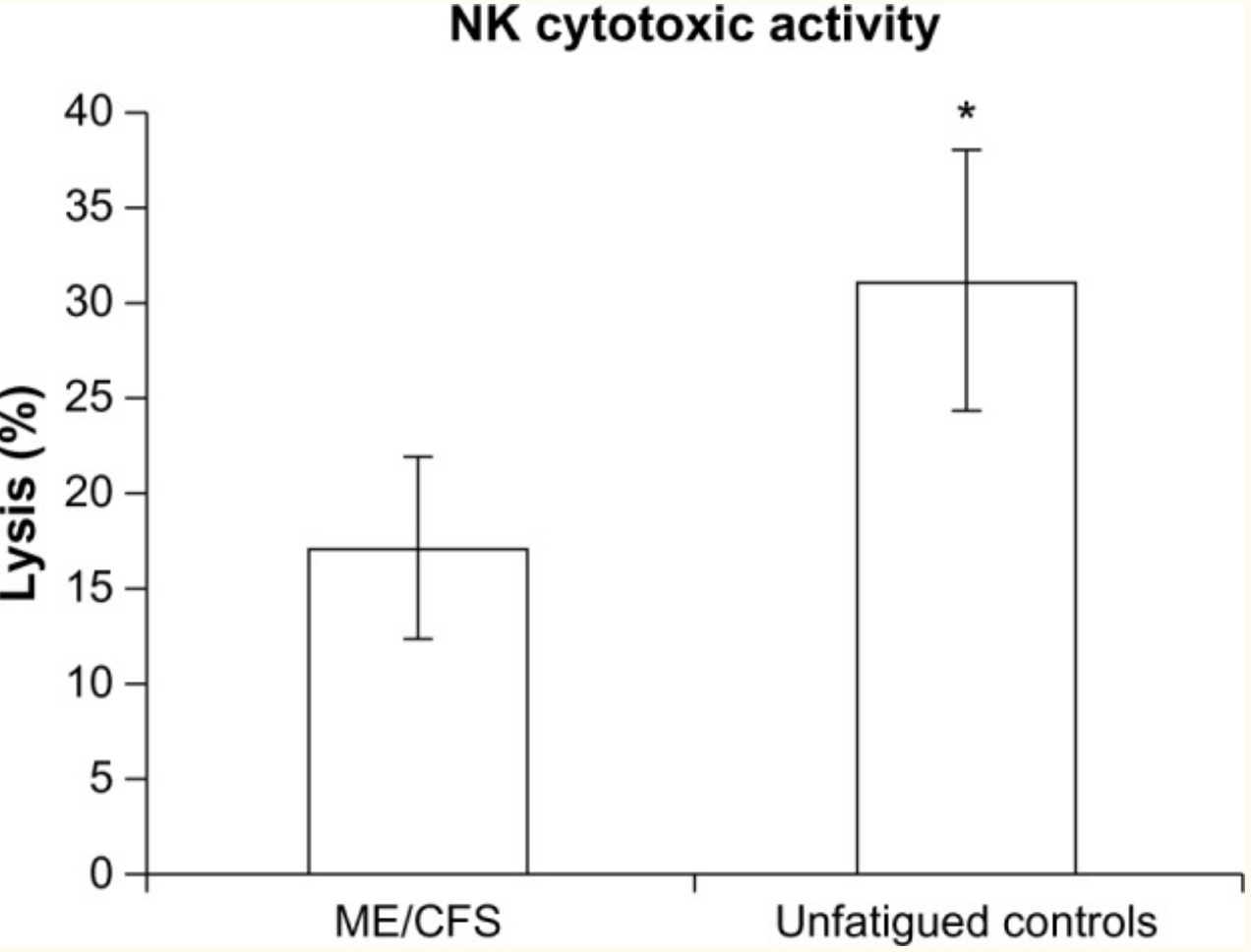

One fairly consistent finding for ME/CFS patients is a reduction in natural killer cells. A type of white blood cell, natural killer (NK) cells are part of the innate immune response. They target tumor cells for destruction and are also vital for responding to viral infections by destroying infected cells.[ref]

Calcium ions play numerous roles in the activation of different cellular processes. Researchers have found that patients with ME/CFS are likely to have impaired calcium ion channel function via the TRPM3 channel. They link this to reduced TRMP3 function on natural killer cells in people with ME/CFS compared to healthy controls. Several variants in the TRPM3 gene are more often found in people with ME/CFS.[ref]

NLRP3 and fatigue:

Another innate immune system component, the NLRP3 inflammasome, is also implemented in fatigue syndromes, including ME/CFS and MS.[ref][ref]

NLRP3 is a linchpin at the start of the immune cascade. Essentially, when NLRP3 activates, it causes caspase-1 activation, which in turn activates interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-18 (IL-18). IL-1β and IL-18 are proinflammatory cytokines that cause rapid cell death (pyroptosis) as well as initiating other inflammatory responses. IL-1B also alters the integrity of the blood-brain barrier.[ref]

NLRP3 activation can develop due to microbes (including coronaviruses) as well as ethanol, amyloid-beta (Alzheimer’s), and alpha-synuclein (Parkinson’s).

Researchers often use animal models in chronic fatigue research, and animal studies point to the continued activation of NLRP3.

Using a mouse model with the NLRP3 gene inactivated, the researchers showed that the mice had reduced fatigue behavior after forced exercise. The knock-out model also showed decreased IL-1β. On the other hand, mice with NLRP3 intact had increased fatigue behavior and increased IL-1β after repeated forced exercise.[ref]

In addition to NLRP3 being activated by viral pathogens, it can also be triggered by mitochondrial dysfunction.[ref] This brings us to the next topic of mitochondrial dysfunction in chronic fatigue…

Mitochondria, cellular energy, and interferon:

Mitochondria are the organelles responsible for the majority of cellular energy — the ‘powerhouse’ of the cell.

When you learn about mitochondria, the Krebs cycle, and the electron transport chain in biology class, a dimensional picture forms of a cellular battery cranking out energy in the form of ATP.

Cellular energy is, of course, vital to well-being. Your muscles and brain can’t work well when lacking energy. So a mitochondrial connection to fatigue is common sense. But why would the fatigue continue after an illness resolves?

The role of mitochondria in the cell goes beyond just generating energy. Mitochondria are constantly changing – fusing together and splitting into two. When a mitochondrion is no longer functioning correctly, it degrades and recycles via a process called mitophagy (autophagy of mitochondria).

In addition to activating the NLRP3 inflammasome cascade (IL-1β and IL-18), damaged mitochondria can trigger interferons and other pro-inflammatory cytokines. Specifically, when mitochondrial DNA leaks, it triggers the immune response, including interferon activation, as a danger signal from the damaged mitochondria.[ref]

Some viral infections also trigger mitophagy, or mitochondrial destruction, which works to help the virus evade the immune response.[ref]

Thus, we have immune system activation causing mitochondrial damage as well as mitochondrial damage-causing immune system activation. In a trap of decreased cellular energy, fatigue persists.

MicroRNAs and gene expression:

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short strands of RNA that can bind to mRNA and prevent it from being translated into its protein. This is one way that the cells moderate gene expression — fine-tuning how much of a specific protein is made from a gene.

The idea that certain cellular processes are turned down in ME/CFS makes sense and fits with symptoms and the research. MiRNAs are one way that this could happen.

One key here is that each miRNA can affect gene expression for multiple genes. There are about 5,000 different miRNAs, with different miRNAs active in specific cell types. MiRNAs can also be released from cells in extracellular vesicles, circulating and affecting the body as a system.

Here’s my full article on miRNA if you want more background.

Let’s take a look at some of the research studies on miRNA changes in ME/CFS patients:

Endothelial function and eNOS: A 2021 study looked at five specific miRNAs involved in endothelial function. The results showed: “miR-21, miR-34a, miR-92a, miR-126, and miR-200c are jointly increased in ME/CFS patients compared to healthy controls.”[ref] MiR-21 and miR-126 regulate eNOS and endothelial function.[ref] MiR-21 is found abundantly in macrophages and plays a key role in regulating the anti-inflammatory response in macrophages.[ref]

Immune response, cellular energy: A study involving 40 ME/CFS patients and 20 healthy controls found five upregulated miRNAs (miR-127-3p, miR-142-5p, miR-143-3p, miR-150-5p, and miR-448), and downregulated (miR-140-5p). This study chose to look at miRNAs that had previously been identified as differentially expressed in people with ME/CFS. A pathway analysis of how those specific miRNAs interact shows that they affect cytokine signaling, mTOR, and the immune response to microbial infections.[ref]

To add a little more complexity here – miRNAs are affected by SNPs in their DNA as well as SNPs in the mRNAs that they bind to.

Fibromyalgia, chronic post-SARS, and persistent fatigue

A small study in 2011 looked at the similarities between what the authors called chronic post-SARS (SARS-CoV-1) and fibromyalgia patients. The study found that people with chronic post-SARS had persistent fatigue, muscle pain, weakness, depression, and non-restorative sleep – which overlapped with the symptoms of people diagnosed with fibromyalgia and ME/CFS. Interestingly, the fibromyalgia and post-SARS patients had a high EEG cyclical alternating sleep pattern rate.[ref]

Transposable Elements: beyond viruses to infection mimicry

Getting a little deeper into the science here… stick with me. This stuff is interesting!

One area of research in ME/CFS ties the immune system activation to the viral DNA encoded in our human genome. Not everyone with ME/CFS, fibromyalgia, or similar diagnoses has altered levels of viruses or a known viral onset. A possible answer may lie in the ‘fossil viruses’ encoded into the human genome.

Your DNA – your genome – is the ‘code’ for your genes, but most of your DNA doesn’t code for protein-coding genes. In fact, about 45% of the genome is made up of transposable elements. These sections of DNA move around within the genome and are sometimes called ‘jumping genes’.

Methylation represents one method of controlling which genes – or which sections of the genome – get transcribed into RNA. This is just one epigenetic way cells control which genes turn off or on. In methylation, a methyl tag that binds to the right spot on your DNA turns off a gene.

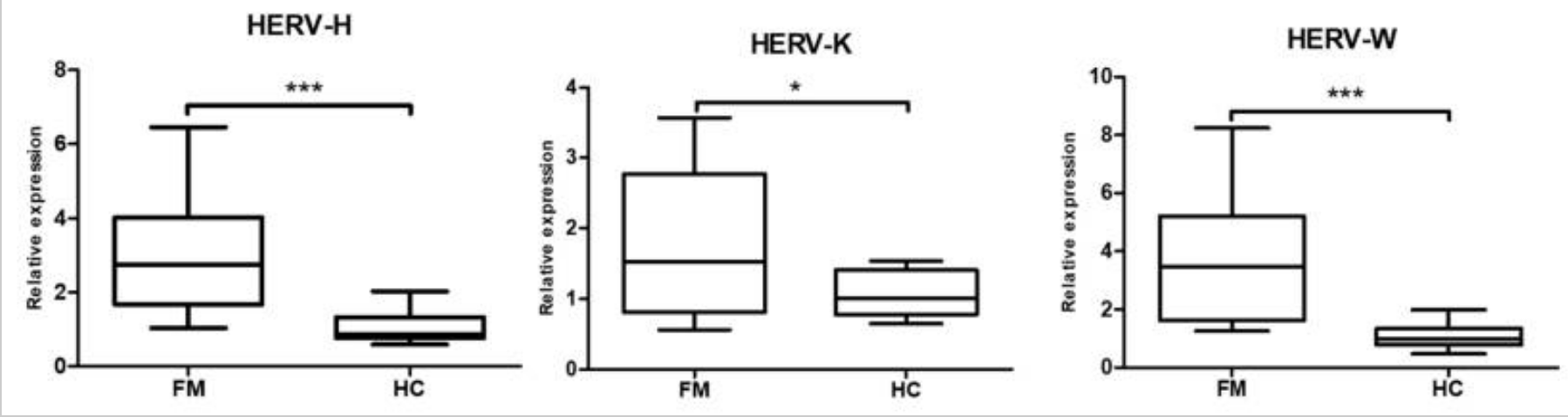

A recent study looked at methylation patterns in people with fibromyalgia and ME/CFS. The researchers found that methylation patterns were different from the healthy control group, and one large difference was in the methylation patterns in the transposable elements.

The study focused on a section known as HERV-K, which is an endogenous retrovirus found in the non-coding part of the genome. An endogenous retrovirus is a section of our human DNA that was a likely integration of a virus or provirus incorporated into the genome millions of years ago. Researchers estimate about 4-8% of the human genome’s composition includes endogenous retroviruses. (Here’s a good article on HERVs, if you’re interested)

The results showed that people with fibromyalgia had increased expression of the HERV-H, HERV-K, and HERV-K. This corresponded with increased interferon-beta and interferon-gamma. The researchers theorize that an infection mimicry state could be a cause of fibromyalgia and ME/CFS.[ref]

Continuing effects after a viral infection

Long Covid is making headlines, with symptoms for some people mimicking those of ME/CFS. However, the aftereffects of a virus triggering chronic tiredness or pain are not a new phenomenon. My focus here is on the mechanisms that have been proven for other fatigue or pain-related conditions. Hopefully, the information will be relevant both for long Covid and for individuals with previous fatigue-related conditions.

There’s more to this story: I want to say up front that I’m not an expert. I’m merely gathering some of the research, but this is just the tip of the information iceberg. So please take this article as a starting point rather than a definitive treatise on the topic.

Why do viral infections make us fatigued?

You know that feeling of being unable to get out of bed when you’re sick…too tired to sleep, too tired even to read, and you just want to lay there? That is the type of fatigue we are talking about here.

But why does fatigue (and muscle ache) happen when fighting off certain pathogens?

Doctors used to say a fever caused the fatigue, but more recent research shows that is likely incorrect. Instead, it is neuroinflammation – inflammation in the central nervous system – causing fatigue when you have a virus. This doesn’t mean the virus is in your brain, but rather the inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and interferon, are acting on the central nervous system. The brain then suppresses activity throughout the body.[ref]

An interesting animal study showed that ‘sickness behavior’ and cognitive dysfunction go together with viral illnesses. One key to the behavioral changes is the blood-brain barrier interferon receptor, which, when activated by interferon, releases a cytokine into the brain.[ref]

Chronic Active Epstein-Barr virus:

Switching gears from ancient retrovirus viruses in our genes to the current virus that almost every person has in their body…

Epstein-Barr is a herpes virus that causes few symptoms in children, but in teens and young adults, it causes mononucleosis. The virus is spread through contact with saliva, and almost everyone (>90% of people) has it by the time they are an adult. The virus sticks around in a latent form for the rest of your life. For a few people, Epstein-Barr can reactivate later in life, causing various problems for people.

Symptoms of mono include extreme fatigue, head and body aches, fever, malaise, and swollen glands. For most teens and young adults, the symptoms will subside within a few weeks.

Chronic active Epstein-Barr virus (CAEBV) is a rare syndrome where the virus stays active, causing long-term illness. Patients have prolonged mono-like symptoms, and most show unusual T-cells or natural killer cells. Due to the prevalence in certain population groups, researchers think there is a genetic susceptibility component.[ref] Rare mutations linked to immunodeficiency have been tied to chronic active Epstein-Barr.[ref]

For most people, though, the Epstein-Barr virus hangs out in a latent state and avoids immune system detection in unique ways. One of the proteins coded for by the virus is very similar to human IL-10, which is an immune system molecule that dampens the immune response. Additionally, Epstein-Barr is an enveloped virus, and the host’s cell membrane creates the envelope. So it escapes detection by looking like ‘self’.[ref]

Many autoimmune diseases, such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and Sjögren’s syndrome, are linked to Epstein-Barr as a contributing factor.[ref]

Prolonged fatigue after West Nile Virus :

Research shows that a lot of people experience prolonged fatigue for six months or more after having West Nile virus. West Nile is a mosquito-borne illness that is prevalent across the US in some years, with an estimated 3 million people in the US with the disease by 2010.[ref] West Nile virus is transmitted to humans from birds via mosquitoes, and a number of other animals can also carry the disease.

While the majority of people with West Nile virus are asymptomatic, about 20% of people will experience fever, headache, weakness, and muscle aches. Around 1% of people will develop severe neurological symptoms, including encephalitis and myocarditis. Risk factors include being over 60 and having comorbidities. The case fatality rate for people with symptomatic West Nile virus is 3-13%, according to the CDC.[ref][ref]

In a study of people with West Nile in Houston, TX, about 20% of the symptomatic people in the study still had continuing fatigue up to 8 years later. The study participants with continuing symptoms also had elevated cytokine levels.[ref]

Other research points to almost half of people with more severe cases of West Nile having long-term symptoms from it. The NLRP3 inflammasome activation is important in fighting off West Nile, as is interferon.[ref]

Long COVID:

Early on in the pandemic, a research study found that about 17% of COVID-19 patients continued to have fatigue symptoms after their illness. About 3% met the criteria for ME/CFS. The researchers also included PTSD in the study and found no overlap between patients with PTSD and CFS/ME.[ref]

A May 2021 study sheds more light on the similarity between Long-COVID, ME/CFS, and chronic viral fatigue. The study found that 67% of the long COVID patients had reactivated Epstein-Barr virus titers (compared to only 10% in the control group). Symptoms of Epstein-Barr virus (fatigue, brain fog, sleep problems, muscle aches, headaches, gastrointestinal issues, and skin rash) overlap completely with long COVID symptoms.[ref]

Read more about long Covid genes and studies here.

ME/CFS Genotype Report

The research studies for ME/CFS, fibromyalgia, and other post-infectious conditions show a theme of an altered immune system response, which is clearly shown in the SNPs below. Many of these immune system genetic variants also overlap with autoimmune diseases and the innate response to different pathogens.

Related Articles and Topics:

BH4: Tetrahydrobiopterin Synthesis, Recycling, and Genetic SNPs

Is Inflammation Causing Your Depression and Anxiety? The Science Behind the Link

HPA Axis Dysfunction: Understanding Cortisol and Genetic Interactions

Debbie Moon is the founder of Genetic Lifehacks. Fascinated by the connections between genes, diet, and health, her goal is to help you understand how to apply genetics to your diet and lifestyle decisions. Debbie has a BS in engineering from Colorado School of Mines and an MSc in biological sciences from Clemson University. Debbie combines an engineering mindset with a biological systems approach to help you understand how genetic differences impact your optimal health.