Key takeaways:

~ The blood clotting process involves proteins like von Willebrand factor (VWF) and ADAMTS13, which can be influenced by genetic variants.

~ Von Willebrand factor (VWF) plays a crucial role in clotting, and its size and reactivity are modulated by the body to prevent unwanted clotting.

~ People with type O blood have lower average levels of VWF, which is linked to a slightly lower risk of heart disease and strokes due to clots.

~ ADAMTS13 is an enzyme that breaks apart VWF, and reduced levels of ADAMTS13 can increase the risk of small blood clots and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP).

Clotting : Von Willebrand Factor and ADAMTS13

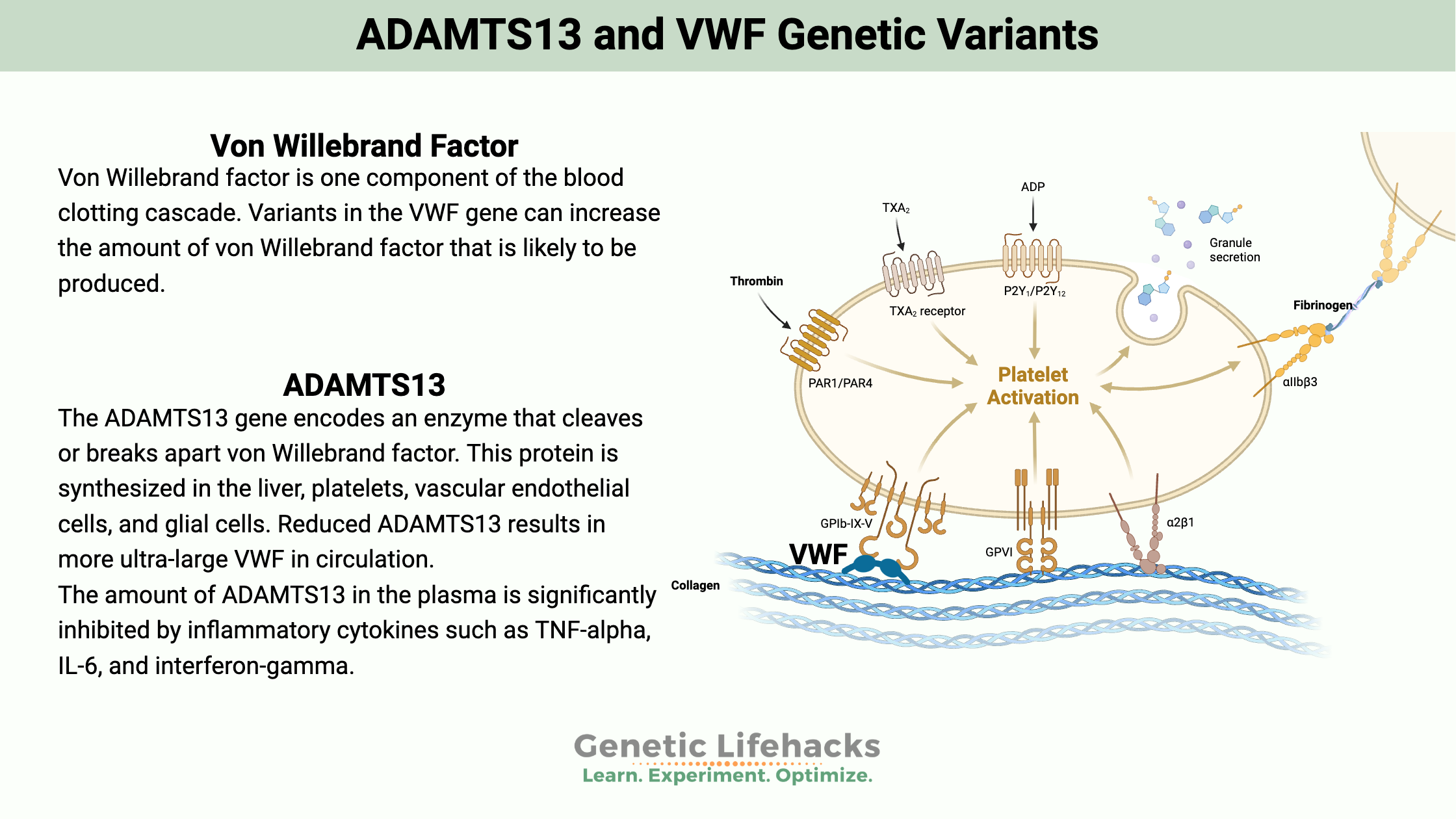

When you get a cut, it activates a cascade of events to form a clot. Platelets rush in to join together with the lining of the blood vessel, plugging up the leak. Fibrinogen is activated to shore up the clot, and then a continual breaking down, remodeling, and reforming of the clot happens as the wound heals.

This process of forming a clot and activating platelets involves a number of proteins made by the body. Genetic variants, of course, cause some people to have different clotting factors, which can increase the risk of small blood clots.

This article digs into just two of the genes involved in creating a blood clot. I’ll explain how a low platelet count can be caused by increased platelet activation due to increased von Willebrand factor or decreased ADAMTS13. If you are interested, this may tie in with my article on Adenovirus-vector vaccines, blood clots, and platelets.

Von Willebrand Factor: essential in clotting

Von Willebrand factor is one component of the blood clotting cascade. Epithelial cells that line the blood vessels release von Willebrand factor, which can bind to platelets. Platelets can also release von Willebrand factor (VWF).

VWF is a protein that can have multiple sizes, such as ultra-large multimeric glycoproteins – meaning that it can be a bigger conglomeration of von Willebrand factor protein, or it can be broken up into smaller molecules.

Size is important here. Ultra-large von Willebrand factor is very reactive and could cause unwanted blood clotting. The body modulates the reactivity by breaking it into smaller fragments, which are less reactive.[ref]

Blood type and VWF:

While von Willebrand factor is being synthesized, it interacts with certain glycans that are also important in your blood type.

People with type O blood have lower average levels of von Willebrand factor.[ref] A rare blood type called Bombay blood group is linked to even lower VWF levels.[ref]

Lower levels of VWF in people with type O blood link to a slightly lower risk of heart disease and strokes due to clots.[ref]

ADAMTS13: preventing too much clotting

The ADAMTS13 gene encodes an enzyme that cleaves or breaks apart von Willebrand factor. This protein is synthesized in the liver, platelets, vascular endothelial cells, and glial cells.[ref]

The amount of ADAMTS13 in the plasma is significantly inhibited by inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha, IL-6, and interferon-gamma.[ref]

Reduced ADAMTS13 results in more ultra-large VWF in circulation.[ref]

A deficiency in ADAMTS13 can increase the risk for small clots to form in small blood vessels, known as platelet microthrombi. Low levels of ADAMTS13 can also increase the risk of heart attacks and strokes caused by blood clots.[ref][ref]

A genetic disease called Upshaw-Schulman Syndrome is caused by mutations in ADAMTS13. It causes the genetic form of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is characterized by a low platelet (thrombocytopenia), and damaged red blood cells (microangiopathic hemolytic anemia).

TPP can either be an autoimmune disease (antibodies against ADAMTS13) or due to rare genetic mutations in ADAMTS13.

The decrease in ADAMTS13 allows for more of the ultra-large von Willebrand factor.

This leads to small blood clots in the smallest blood vessels due to platelet activation and aggregation. After activation, the body doesn’t reuse platelets. Instead, they are destroyed and cleared out in the liver or spleen.[ref]

Thus the decreased ADAMTS13 leads to both blood clots and low platelet levels (thrombocytopenia).

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura due to an ADAMTS13 mutation is a rare genetic disease with a prevalence of 4 in a million. Most cases of TTP are due to an autoimmune cause, and pregnancy is one trigger of TTP.[ref][ref]

There is a higher than normal, but still rare, prevalence in Norway of ADAMTS13 mutations.[ref]

ADAMTS13 and VWF Genotype Reports:

Lifehacks:

Take the information about your blood clot genetic risk factors as a ‘heads up’ and seek treatment for symptoms of a blood clot. Symptoms of a blood clot can include heat, swelling, or pain in an arm or leg. Clots can also cause trouble breathing, edema, or chest pain.

Stop smoking:

If you carry the variants that cause lower ADAMTS13, this is a really good reason not to smoke. Cigarette smoking also decreases ADAMTS13, and the combination could increase clot risk.[ref]

Know and act:

Important to know that TTP can usually be successfully treated if you seek medical help quickly.

Signs and symptoms of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) include:[ref]

- petechiae – pinpoint size dots on the skin caused by bleeding under the skin

- fatigue

- paleness

- fast heart rate

- purplish bruises on the skin

- headache, confusion, stroke symptoms

- fever

Learn more:

Here’s a video on how a clot forms if you are interested:

Related Articles and Topics:

References:

Abegaz, Silamlak Birhanu. “Human ABO Blood Groups and Their Associations with Different Diseases.” BioMed Research International, vol. 2021, Jan. 2021, p. 6629060. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6629060.

Camilleri, R. S., et al. “A Phenotype-Genotype Correlation of ADAMTS13 Mutations in Congenital Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura Patients Treated in the United Kingdom.” Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis: JTH, vol. 10, no. 9, Sept. 2012, pp. 1792–801. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04852.x.

De Cock, E., et al. “The Novel ADAMTS13-p.D187H Mutation Impairs ADAMTS13 Activity and Secretion and Contributes to Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura in Mice.” Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis: JTH, vol. 13, no. 2, Feb. 2015, pp. 283–92. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.12804.

de Vries, Paul S., et al. “Genetic Variants in the ADAMTS13 and SUPT3H Genes Are Associated with ADAMTS13 Activity.” Blood, vol. 125, no. 25, June 2015, pp. 3949–55. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-02-629865.

Hanson, E., et al. “Association between Genetic Variation at the ADAMTS13 Locus and Ischemic Stroke.” Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, vol. 7, no. 12, Dec. 2009, pp. 2147–48. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03617.x.

Ma, Qianyi, et al. “Genetic Variants in ADAMTS13 as Well as Smoking Are Major Determinants of Plasma ADAMTS13 Levels.” Blood Advances, vol. 1, no. 15, June 2017, pp. 1037–46. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2017005629.

Matsukawa, Masakazu, et al. “Serial Changes in von Willebrand Factor-Cleaving Protease (ADAMTS13) and Prognosis after Acute Myocardial Infarction.” The American Journal of Cardiology, vol. 100, no. 5, Sept. 2007, pp. 758–63. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.03.095.

Mufti, Ahmad H., et al. “The Common VWF Single Nucleotide Variants c.2365A>G and c.2385T>C Modify VWF Biosynthesis and Clearance.” Blood Advances, vol. 2, no. 13, July 2018, pp. 1585–94. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2017011643.

O’Donnell, James S., et al. “Bombay Phenotype Is Associated with Reduced Plasma-VWF Levels and an Increased Susceptibility to ADAMTS13 Proteolysis.” Blood, vol. 106, no. 6, Sept. 2005, pp. 1988–91. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2005-02-0792.

Pagliari, Maria Teresa, et al. “Next-Generation Sequencing and In Vitro Expression Study of ADAMTS13 Single Nucleotide Variants in Deep Vein Thrombosis.” PloS One, vol. 11, no. 11, 2016, p. e0165665. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165665.

Roose, Elien, et al. “Anti-ADAMTS13 Antibodies and a Novel Heterozygous p.R1177Q Mutation in a Case of Pregnancy-Onset Immune-Mediated Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura.” TH Open: Companion Journal to Thrombosis and Haemostasis, vol. 2, no. 1, Jan. 2018, pp. e8–15. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1615252.

Rurali, Erica, et al. “ADAMTS13 Predicts Renal and Cardiovascular Events in Type 2 Diabetic Patients and Response to Therapy.” Diabetes, vol. 62, no. 10, Oct. 2013, pp. 3599–609. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.2337/db13-0530.

Saha, M., et al. “Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Potential Novel Therapeutics.” Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis: JTH, vol. 15, no. 10, Oct. 2017, pp. 1889–900. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.13764.

Schettert, Isolmar T., et al. “Association between ADAMTS13 Polymorphisms and Risk of Cardiovascular Events in Chronic Coronary Disease.” Thrombosis Research, vol. 125, no. 1, Jan. 2010, pp. 61–66. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2009.03.008.

Smith, Nicholas L., et al. “Genetic Variation Associated with Plasma von Willebrand Factor Levels and the Risk of Incident Venous Thrombosis.” Blood, vol. 117, no. 22, June 2011, pp. 6007–11. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-10-315473.

Swystun, Laura L., and David Lillicrap. “Genetic Regulation of Plasma von Willebrand Factor Levels in Health and Disease.” Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis : JTH, vol. 16, no. 12, Dec. 2018, pp. 2375–90. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.14304.

Underwood, M. I. The Relationship between ADAMTS13 Genotype and Phenotype in Congenital Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura and Characterisation of ADAMTS13 Mutants. UCL (University College London), 28 Feb. 2015. discovery.ucl.ac.uk, https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1462706/.

VCV000068815.18 – ClinVar – NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/68815/. Accessed 27 June 2022.

von Krogh, A. S., et al. “High Prevalence of Hereditary Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura in Central Norway: From Clinical Observation to Evidence.” Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis: JTH, vol. 14, no. 1, Jan. 2016, pp. 73–82. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.13186.

Yang, Junxian, et al. “Insights Into Immunothrombosis: The Interplay Among Neutrophil Extracellular Trap, von Willebrand Factor, and ADAMTS13.” Frontiers in Immunology, vol. 11, Dec. 2020, p. 610696. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.610696.

Zheng, X. Long. “ADAMTS13 and von Willebrand Factor in Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura.” Annual Review of Medicine, vol. 66, 2015, pp. 211–25. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-061813-013241.