Key takeaways:

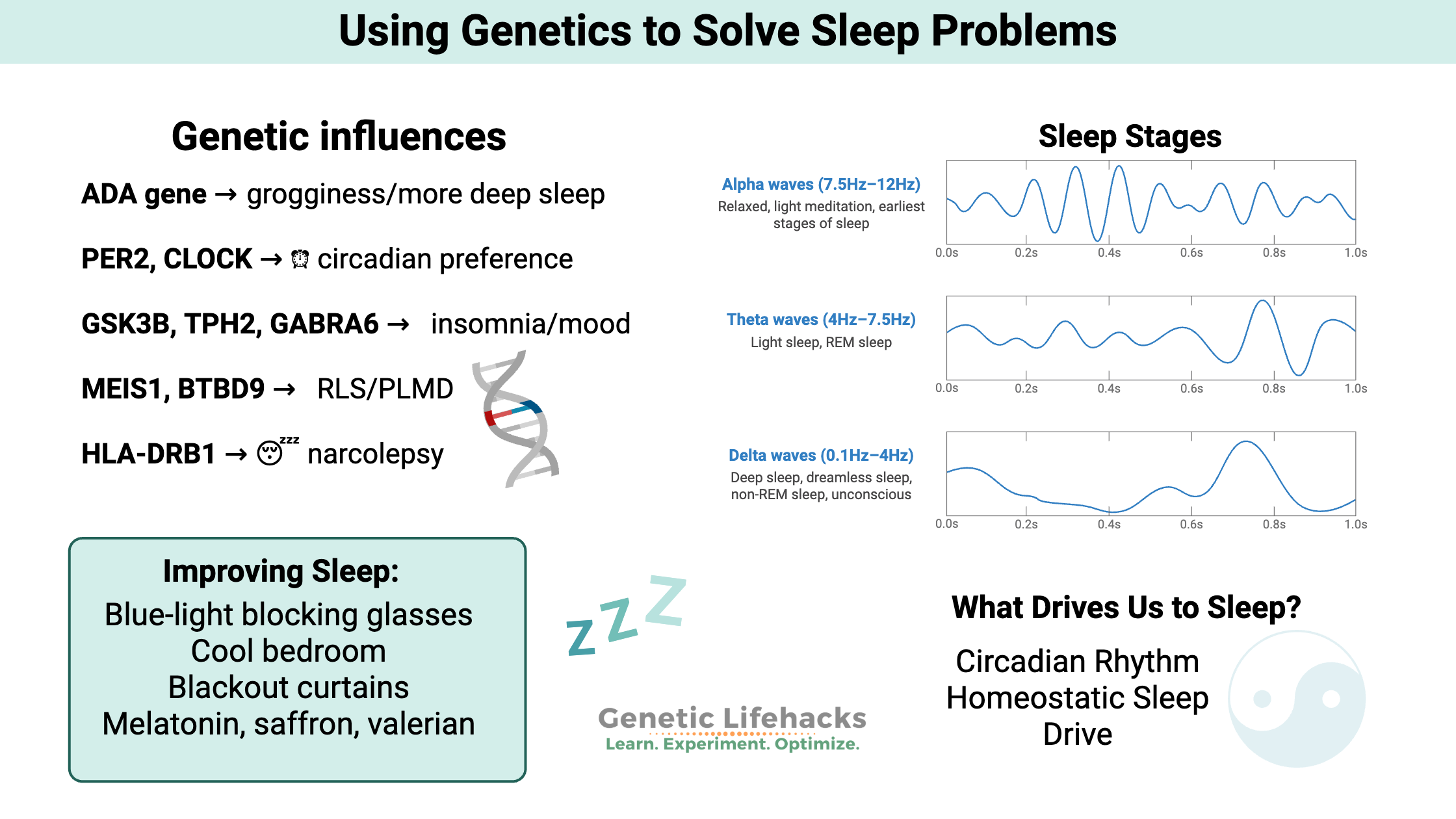

~ Many sleep disorders, including insomnia and restless leg syndrome, have a strong genetic component. Specific gene variants can affect sleep quality, timing, and duration.

~ Deep sleep and REM sleep are essential for memory, emotional regulation, and physical health. Sleep deprivation is linked to impaired cognition, cardiovascular problems, and obesity.

~ Adenosine builds up during the day to induce sleep pressure, while neuropeptide S and neurotransmitters like GABA and serotonin influence sleep stages and quality.

~ Exposure to blue light at night disrupts melatonin production and circadian rhythms. Reducing light exposure in the evening can improve sleep.

What is sleep, and why do we need it?

“Why do we sleep?” turns out to be a more difficult question to answer than you would think.

We are asleep for about a third of our lives. All animals, both big and small, sleep. So you would think that scientists would know exactly why and how sleep works… Instead, we have almost as many questions about sleep as we have answers.

Let’s look at the definition of sleep from a prominent sleep medicine textbook: “Sleep is a recurring, reversible neuro-behavioral state of relative perceptual disengagement from and unresponsiveness to the environment. Sleep is typically accompanied (in humans) by postural recumbence, behavioral quiescence, and closed eyes.”[ref] Yep – big words for laying down, closing your eyes, and going to sleep.

The important thing here, though, is what goes on in the brain while you sleep. While your body is inactive (hopefully), your brain is doing some pretty cool and weird stuff while you sleep. Plus, there are different metabolic processes going on in your body while you are asleep compared to when you’re awake.

Why is sleep so important?

While you sleep, your brain consolidates memories — it makes the things that you learned during the day stick in your brain. This has been known for a long time and is something that researchers frequently experiment with.[ref]

Recently, researchers experimented with just decreasing certain stages of sleep and showed that the neuroplastic changes to the brain in learning happen specifically during deep sleep.[ref]

Another role of sleep is to reduce oxidative stress in the gut. A couple of studies in animals show that the lack of sleep causes death due to oxidative stress in the intestines.[ref]

Studies of sleep deprivation show there can be devastating consequences.

- For most people, sleep deprivation causes a decrease in speed and accuracy in tests for attention, working memory, processing speed, short-term memory, and reasoning.[ref]

- One-third of accidents in a survey of commercial truck drivers were caused by drowsy driving due to sleep deprivation.[ref]

- According to the NTSB, going 20+ hours without sleep is equivalent to driving legally drunk. And your risk of being in a car crash goes up 3-fold![ref]

- This pretty much sums up the rest of the effects of sleep deprivation: ‘studies have shown that short sleep duration is associated with an increased incidence of cardiovascular diseases, such as coronary artery disease, hypertension, arrhythmias, diabetes, and obesity, after adjustment for socioeconomic and demographic risk factors and comorbidities.'[ref]

Stages of sleep:

When you sleep, your brain goes through different periods of activity. These are categorized into slow-wave sleep and REM (rapid eye movement) sleep.

Slow-wave sleep can further be broken down into deep sleep and light sleep. About 50% of sleep time (in adults) is light, non-REM sleep.

Most of your deep sleep comes during the early part of the night, while the latter half of the night has much more REM sleep.[ref]

Brain waves during sleep:

Your brain waves slow down during sleep, becoming more synchronized with lower frequency and higher amplitude.

- Light sleep and REM sleep = theta waves

- Deep sleep = delta waves

During non-REM sleep, the brain is consolidating memories, which is important in learning and recall. During REM sleep, emotions are being recorded and modulated within the hippocampus.[ref]

Different types of neurons are firing or silenced during the sleep stages. During NREM sleep, serotonergic and noradrenergic neurons decrease their firing rate, and they become nearly inactive during REM sleep. Acetylcholine levels in the brain are at their low point during NREM sleep, but levels rise considerably during REM sleep.

Sleep Disorders and Genes:

Let’s take a look at some of the ways that sleep can be disrupted or disturbed – along with the genetic connections that are included in the Genotype report section below.

| Disorder | Prevalence | Key Genetic Contributors | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insomnia | 10% adults, 22% elderly | GSK3B, PER2, TPH2, GABRA6 | Difficulty falling/staying asleep |

| Restless Leg Syndrome | ~10% US population | MEIS1, BTBD9, MAP2K5, PTPRD | Urge to move legs, sleep disruption |

| Narcolepsy | 1 in 2,000 | HLA-DRB11501, HLA-DQB10602 | Excessive daytime sleepiness |

| Circadian Rhythm Disorders | Variable | CLOCK, PER2, AANAT | Disrupted sleep timing |

Difficulties with sleep drive and circadian rhythm:

We feel the need to sleep each night due to two causes:

- changing levels of our circadian rhythm genes

– and – - increased homeostatic sleep drive

Feeling sleepy:

The homeostatic sleep drive is what researchers call the build-up over the course of the day for the need to sleep. This is mainly driven by a build-up of adenosine in the brain, which is then cleared out during sleep.

Adenosine is part of the ATP (adenosine triphosphate) molecule used for cellular energy. The ATP molecule stores energy in its bonds and releases energy as the bonds with phosphate are broken. As you use energy over the course of the day, you build up adenosine in the brain.[ref] Interestingly, caffeine makes you feel more awake by blocking the adenosine receptors, thus making your brain think that not as much adenosine has built up.

Not clearing out adenosine quickly enough overnight can cause a person to still feel groggy when they wake up in the morning. A variant of the ADA (adenosine deaminase) gene is associated with reduced activity, causing adenosine to be cleared away less quickly. Variants in the ADA gene are linked with more deep sleep, but the slower clearance of adenosine means that a short night’s sleep leaves the person feeling groggier than normal.

Neuropeptide S is a neuropeptide found mainly in the amygdala. Animal studies show that when neuropeptide S binds to its receptor, it induces wakefulness. At night, neuropeptide S reduces NREM sleep.[ref]

A gut peptide, CCHa1, was discovered a couple of years ago to be involved in sleep. Higher levels of CCHa1 make it harder to be aroused from sleep. Interestingly, for animals, higher amounts of protein in the diet increase the sleep-promoting peptide at night.[ref]

Circadian rhythm:

The body’s circadian rhythm is the 24-hour built-in molecular clock. Many different processes in the body occur at different times of the day based on the circadian clock. For example, the enzymes that you produce to break down food are driven by the timing of your normal eating patterns. You may notice that eating dinner several hours later than normal doesn’t always digest as well.

We (all of us humans) are diurnal, which means our circadian rhythm is set up for being up and active during the day and sleeping or inactive in the dark.

Yep, we are flexible, and people can change over to work the night shift. But that change can come with health consequences, more for some than others.

The genes that control the core circadian rhythm can affect sleep quality as well as mood and cognitive function.

Related article: Circadian rhythm genes and mood disorders

What causes insomnia?

Everyone, at some point, knows the pain of a sleepless night. For some, though, this is an all too frequent occurrence. About 10% of adults and 22% of the elderly are estimated to have an insomnia disorder.[ref]

Insomnia can be either a problem with initially falling asleep or with waking up in the early morning hours and not being able to fall back to sleep. There are several terms applied to different types of insomnia:

- Sleep onset insomnia – problems with falling asleep

- Early waking (terminal insomnia) – waking up too early and not falling back to sleep

- Sleep maintenance insomnia – waking up one or more times in the night and struggling to get back to sleep

Genetics and insomnia:

Heritability estimates from twin studies show that insomnia is around 50% genetic; genes lend susceptibility along with environmental factors. The biggest genetic influence is for sleep maintenance insomnia, where people have a hard time staying asleep rather than difficulty falling asleep. [ref][ref]

Problems sleeping go hand-in-hand with depression. 80-90% of people with major depression experience insomnia of some sort, with about half of them experiencing severe insomnia.[ref]

- GSK3B is a gene associated with both circadian rhythm and mood disorders. A variant of GSK3B has been shown to double the risk of severe insomnia in depressed patients. These patients also had a greater insomnia response to antidepressant therapy.[ref] Note that this gene is also affected by lithium, affecting bipolar disorder.

- PER2: One of the core circadian clock genes, PER2, has variants with strong links to insomnia.

- TPH2 gene: Waking up really early and not being able to fall back to sleep is a form of insomnia known as sleep maintenance insomnia. A variant in the TPH2 gene, which converts tryptophan into serotonin and then melatonin, has been associated with an increased risk of sleep maintenance insomnia.

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Genes:

Circadian Rhythms: Genes at the Core of Our Internal Clocks

Circadian rhythms are the natural biological rhythms that shape our biology. Most people know about the master clock in our brain that keeps us on a wake-sleep cycle over 24 hours. This is driven by our master ‘clock’ genes.Restless Leg and Periodic Limb Movement Disorder: Genetics and Solutions

Twitchy legs, restless sleep… That urge to move your legs at night or being woken up with your leg moving rhythmically — both take a toll on sleep quality. And good sleep is foundational for overall health and wellbeing.Genetics and Teeth Grinding (Bruxism)

Bruxism is a condition where you unconsciously clench or grind your teeth. This can occur when sleeping (sleep bruxism) or while you are awake. Bruxism can cause wear on the enamel of the teeth and even cause teeth to crack. Additionally, people with bruxism may have jaw pain, headaches, migraines, or sleep disorders.How to log in to 23andMe and download raw data

Step-by-step instructions on how to download your raw data from 23andMe