Key takeaways:

~ Restless leg syndrome (RLS) and Periodic Limb Movement Disorder (PLMD) can disrupt sleep and have significant long-term effects on your health.

~ Genetic variants play a role in susceptibility to RLS and PLMD.

~ Animal studies shed even more light on the root causes, pointing to a couple of pathways in the brain.

I’m diving into the genetics of restless leg syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder to show how understanding the root causes can help you to find solutions.

Members will see their genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

RLS and PLMD: Science, Solutions, and Genetics

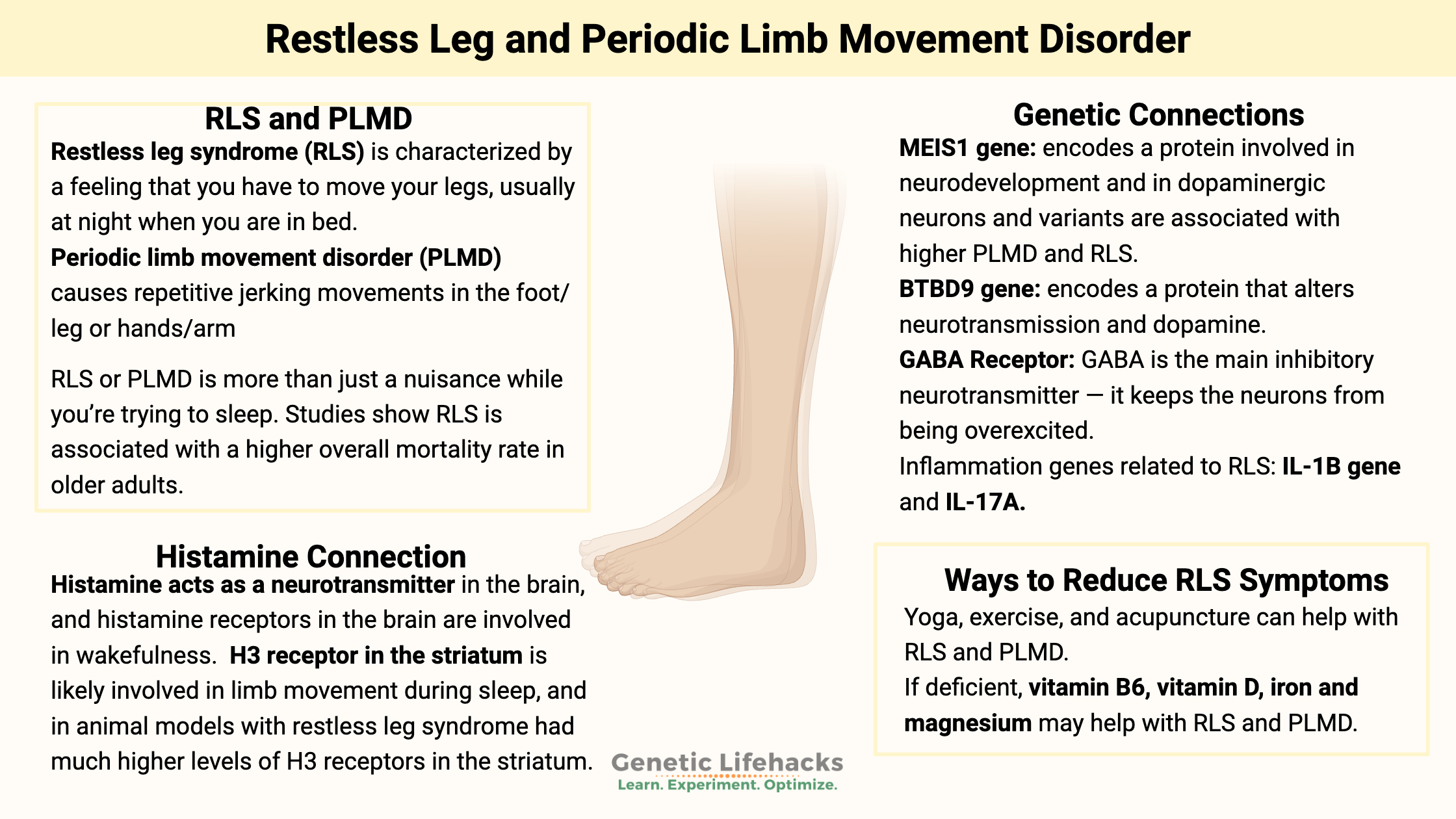

Restless leg syndrome (RLS) is characterized by a feeling that you have to move your legs, usually at night when you are in bed. In some people, it can also affect the need to move their arms also. Restless leg syndrome is estimated to affect between 4 and 14% of adults. It is most prevalent in older women, but it can affect both men and women at any age.

Periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) causes repetitive jerking movements in the foot/leg or hands/arm. For some people, it is an involuntary repetitive movement, such as flapping a hand or jerking a leg, that lasts about a minute at a time.

In contrast to RLS, PLMD is more common in men than women.[ref] PLMD is also called Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep (PLMS). I’ll use PLMD here for consistency throughout the article.

Restless legs and PLMD occur together in many people, but they can also exist separately. Most research studies group the two topics together, and genetically they may have common causes.

Why is this topic important?

RLS or PLMD is more than just a nuisance while you’re trying to sleep. In a study of older men, restless leg syndrome was associated with a higher mortality rate, even after controlling for a number of other variables.[ref]

Genetic studies on restless leg syndrome:

Twin studies show that there is a strong genetic element to RLS, but there are also environmental factors that contribute to the risk of RLS.[ref]

When researchers don’t really understand the cause of a disease, they often use genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to see if they can identify which genetic variants and which genes are involved. It is an approach that removes any preconceived notions about why a disease occurs, but it can also sometimes provide red herrings.

In 2007, genome-wide studies found that the BTBD9 and MEIS1 genes were associated with an increased risk of both restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder.[ref][ref] Since then, numerous studies have been conducted to replicate the findings and to find out why these two genes are so important for RLS and PLMD.

MEIS1 gene function:

The MEIS1 gene codes for a homeobox protein that is involved in turning on and off genes during development and in neurodevelopment. It is expressed in the substantia nigra – the region of the brain involved in dopamine production. MEIS1 is also thought to be involved in the formation of blood cells.[ref]

The substantia nigra is the region of the brain that causes dopamine-related issues in Parkinson’s disease. This is important in RLS and PLMD because the medications available for RLS are Parkinson’s medications.

People with Parkinson’s are at an elevated risk of also having RLS.[ref][ref] Interestingly, mice with half of the normal MEIS1gene function are restless and move 16% more than normal mice. The mice weren’t anxious: they just moved more, traveled longer distances, and were a little speedier.[ref]

Other studies show that decreased MEIS1 causes changes to the cholinergic neurons in the region of the brain that controls voluntary movement (the striatum).[ref]

BTBD9 gene function:

The BTBD9 gene codes for a protein “which modulates transcription, cytoskeletal arrangement, ion conductance, and protein ubiquitination”. Let me break that down a little bit…

If you delete the BTBD9 gene, it alters neurotransmission in the animal. A recent study shows that mice without the BTBD9 gene had enhanced brain activity in the striatum, which controls voluntary movement. The neurons in this area are mostly dopaminergic neurons that contain either dopamine 1 receptors or dopamine 2 receptors. The study showed that lacking BTBD9 caused enhanced activity and excitability in these dopaminergic neurons in the striatum. These mice without BTBD9 were more active when they should be resting, had disturbed sleep, and were more sensitive to temperature.[ref]

Histamine receptors in the brain and PLMD or RLS:

Histamine acts as a neurotransmitter in certain areas of the brain, and histamine receptors in the brain are involved in wakefulness. The H3 receptor is one of the histamine receptors found in the brain.

A 2020 study in an animal model of RLS showed that the H3 receptor in the striatum is likely involved in limb movement during sleep. Activating the H3 receptor with a drug increased motor activity during sleep, and blocking the H3 receptor decreased motor activity during sleep. In addition, those with restless leg syndrome had much higher levels of H3 receptors in the striatum than the normal animals[ref]

The H3 receptor in the brain regulates histamine release through a negative feedback loop. It also regulates the release of dopamine, GABA, and acetylcholine in certain areas of the brain.

If histamine is involved in RLS and PLMD, it would make sense that there would be an overlap with other disorders that involve high levels of histamine due to mast cell activation. This appears to be true. A study of patients with mast cell activation syndrome found that they were about 3 times more likely to have restless leg syndrome than a control group.[ref]

Related article: Histamine receptors, histamine intolerance

Do changes to the brain cause RLS?

Researchers want to know if there are differences in the brains of people with RLS or PLMD. MRI, PET, and SPECT scans have been done to look at the brains of people with RLS. Some people (but not all) with RLS have lower iron stores, which show up on MRI scans. Many of the other studies were inconclusive or had conflicting results.

One study that looked at the results of several different types of brain scans concluded that there may be an evening and nighttime dopamine deficit in the striatum due to increased daytime receptor function.[ref] There is an overall circadian rhythm to dopamine production, and it is naturally lower at night and higher during the day.

Inflammation and RLS/PLMD:

Some studies suggest the role of higher inflammatory cytokines in people with RLS and/or PLMD. [ref]

The question in my mind was whether the inflammation caused the RLS/PLMD or whether the sleep disruption increased the inflammation. Genetics suggest a possible inflammatory cause.

A genetic study found that people with variants in the IL1B (interleukin 1B) and IL-17A genes have a higher risk of RLS/PLMD. IL-1B and IL-17A are inflammatory cytokines, and researchers theorize that higher levels of inflammation in the brain may affect dopamine. [ref]

Iron and RLS:

A number of studies suggest that low levels of iron in the brain may be a contributing factor in some people with RLS. This is based on studies showing that people with RLS are more likely to have low cerebrospinal fluid ferritin. However, most studies show that serum ferritin levels are not different in people with RLS.[ref]

Not everyone with restless legs syndrome has low iron levels. Researchers have investigated whether genetic variants that cause high iron (HFE gene) are protective against RLS, but the conclusion was that the mutations that give people high iron levels do not protect against restless legs.[ref]

So while iron may be part of the picture for some people with RLS, it’s far from the whole story.

Dopamine and RLS:

In addition to the genetic links to dopaminergic neuron function, there are a number of other things that suggest that dopamine levels are important in RLS and PLMD.

Typically, doctors treat RLS and PLMD with dopamine agonist medications that are traditionally used for Parkinson’s disease (a low-dopamine disease). These drugs are effective for some people, but they can have side effects. For example, Sinemet is a dopamine agonist that is commonly prescribed with a long list of side effects.

Too much dopamine in the brain can cause psychosis, and atypical antipsychotics block dopamine receptors. It turns out that a side effect of some of the atypical antipsychotics is that they can cause or worsen RLS.[ref] This presents a picture of dopamine being important at the right level and at the right time of day.

Medications linked to increased risk of PLMD:

A study of patients who had undergone sleep studies for other conditions (insomnia, chronic fatigue) looked for links between medications and PLMD. The results showed that people taking SSRIs, SNRIs, or tricyclic antidepressants were significantly more likely to have PLMD. On the other hand, benzodiazepine and sedative use was negatively correlated with PLMD.[ref]

RLS and PLMD: Genotype Report

The following genes have been shown in research studies to increase or decrease the relative risk of restless leg syndrome and/or PLMD.

Members: Log in to see your data below.

Not a member? Join here.

Why is this section is now only for members? Here’s why…

Lifehacks for Restless Leg or PLMD:

Let’s dive into the research on ways to decrease RLS and PLMD without heavy-duty medications. For information on prescription drugs, please be sure to talk with your doctor.

Physical Ways to Reduce RLS Symptoms:

Increase oxygen and blood flow to the legs:

Several studies suggest that peripheral hypoxia (low oxygen in the legs and arms) is contributing to RLS and PLMD. One study found that PLMD symptoms were worsened by sleeping at high altitudes.[ref] Another study found poor endothelial function in people with RLS.[ref] Another study found lower oxygen levels just in the legs of patients with RLS.

Exercise may help with low oxygen levels in the legs. A recent study on a small group of patients with both restless leg and peripheral artery disease found that frequent, low-intensity exercise helped reduce symptoms.[ref] Other studies also point to exercise possibly helping with restless leg, but not being a cure-all for everyone.[ref]

Yoga was shown to help with restless leg symptoms in a small study (10 people).ref]

Whole-body vibration:

A study tested whether whole-body vibration would increase blood flow. The results showed that skin blood flow in the legs did not increase — but that whole-body vibration did help with RLS.[ref]

Acupuncture:

A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of acupuncture plus gabapentin versus gabapentin alone found that sleep quality increased in people who received acupuncture with their gabapentin.[ref] Another study of acupuncture alone concluded that it ‘might help’, but the data doesn’t show much improvement.[ref]

Diet and Natural Supplements for Restless Leg and PLMD:

Low-Histamine Diet:

The link to histamine receptors in the brain makes a low-histamine diet worth investigating and experimenting with. You can read more about histamine here, and check out the foods that are high vs. low in histamine. Note that there are no research studies showing that a low histamine diet helps with RLS and PLMD. This is an extrapolation from animal studies.

Ideas here include:

- Track what you eat and see if high histamine foods make your PLMD or RLS worse.

- See if eating low histamine foods only at dinner helps your sleep.

- If histamine in foods makes a difference, you could also look into DAO enzyme supplements, which reduce histamine from foods.

Vitamins and Minerals:

Vitamin B6:

A 2022 study found that 40 mg of vitamin B6 helped to reduce the severity of RLS and improve sleep quality.[ref] Vitamin B6 acts as a cofactor in a number of reactions that could affect RLS, including the conversion of tryptophan to serotonin. Perhaps more importantly, vitamin B6 is key to regulating histamine levels. If you’re deficient in vitamin B6, this may be a vitamin to try. Note that 40 mg/day is a moderate amount to supplement. There are reports that high levels of vitamin B6 for long periods of time can cause side effects in the nerves.

Related article: Vitamin B6 – genes, pathways

Magnesium:

A couple of small studies have found that magnesium supplementation at bedtime cuts the incidence of PLMD in half.[ref][ref] This is more likely to help in people who are deficient in magnesium.

Foods high in magnesium include pumpkin seeds, almonds, leafy greens, and black beans. Check out the article below for more information on types of magnesium supplements, as well as other foods high in magnesium.

Related article: Magnesium and your genes

Vitamin D:

If you are low in vitamin D (test to find out), supplemental vitamin D or skin exposure to sunlight may help with RLS. A 2021 study found that vitamin D deficiency is more common in people with RLS. In addition, vitamin D deficiency may affect dopamine levels in the brain.[ref]

Iron:

There is a statistical association between low levels of iron (in the brain) and restless leg syndrome, and a subset of RLS patients improved with supplemental iron. Before supplementing with iron, do a blood test to see what your iron levels are. Iron needs to be in balance, and there are adverse effects of excess. Check your genetic risk for hemochromatosis before supplementing with iron.

Talk with your doctor about getting an iron panel done – or order one yourself through UltaLab Tests or another online lab test ordering service.

One last piece of advice: There are several types of iron pills. Many people find that iron supplements cause constipation. If this is true for you, try iron bis-glycinate, or “gentle iron”.

Dopamine pathways:

In a small study of l-dopa for RLS/PLMD in children with ADHD, l-dopa was found to improve restless leg syndrome.[ref] It also has been shown to help with RLS in people with chronic kidney disease.[ref]

You can get l-dopa by taking Mucuna pruriens, which is an herbal supplement high in l-dopa. It is available online or at your local health food store. There aren’t any studies that I can find on using mucuna pruriens for RLS. The Examine.com article on mucuna pruriens contains a lot of good information on the pros and cons, based on research studies. Be sure to talk with your doctor if you are on any prescriptions about interactions with Mucuna pruriens.

Supplements for blocking inflammation:

EGCG, found in green tea, suppresses the inflammation upregulated by IL1B.[ref] EGCG is available as a supplement or you can get it by drinking green tea during the day.

Curcumin, a component of turmeric, has been found to reduce IL-17 (in an animal study).[ref] Curcumin is available as a supplement.

Related article: Curcumin – Research, Absorption, Genetics

Sulforaphane, an active natural compound found in cruciferous vegetables, has been shown to inhibit IL-17.[ref] You can get sulforaphane as a supplement or by eating broccoli sprouts.

Related article: IL-17 genetic variants

Recap of your genes:

Related Articles and Genes:

Circadian Rhythms: Genes at the Core of Our Internal Clocks

Circadian rhythms are the natural biological rhythms that shape our biology. Most people know about the master clock in our brain that keeps us on a wake-sleep cycle over 24 hours. This is driven by our master ‘clock’ genes.

GABA: Genetic Variants that Impact this Inhibitory Neurotransmitter

GABA (gamma-aminobuyteric acid) is a neurotransmitter that acts to block or inhibit a neuron from firing. It is an essential way that the brain regulates impulses, and low GABA levels are linked with several conditions including anxiety and PTSD.

References:

A Genetic Risk Factor for Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep | NEJM. (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2019, from https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa072743

Bollu, P. C., Yelam, A., & Thakkar, M. M. (2018). Sleep Medicine: Restless Legs Syndrome. Missouri Medicine, 115(4), 380–387.

Ferini-Strambi, L., Carli, G., Casoni, F., & Galbiati, A. (2018). Restless Legs Syndrome and Parkinson Disease: A Causal Relationship Between the Two Disorders? Frontiers in Neurology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.00551

Li, Y., Wang, W., Winkelman, J. W., Malhotra, A., Ma, J., & Gao, X. (2013). Prospective study of restless legs syndrome and mortality among men. Neurology, 81(1), 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e318297eee0

Rizzo, G., Li, X., Galantucci, S., Filippi, M., & Cho, Y. W. (2017). Brain imaging and networks in restless legs syndrome. Sleep Medicine, 31, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2016.07.018

Sarayloo, F., Dion, P. A., & Rouleau, G. A. (2019a). MEIS1 and Restless Legs Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. Frontiers in Neurology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00935

Sarayloo, F., Dion, P. A., & Rouleau, G. A. (2019b). MEIS1 and Restless Legs Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. Frontiers in Neurology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00935

The Role of BTBD9 in Striatum and Restless Legs Syndrome. (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2019, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6787346/

Ylikoski, A., Martikainen, K., & Partinen, M. (2015). Parkinson’s disease and restless legs syndrome. European Neurology, 73(3–4), 212–219. https://doi.org/10.1159/000375493

Aggarwal, Shilpa, et al. “Restless Leg Syndrome Associated with Atypical Antipsychotics: Current Status, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Implications.” Current Drug Safety, vol. 10, no. 2, 2015, pp. 98–105.

Bollu, Pradeep C., et al. “Sleep Medicine: Restless Legs Syndrome.” Missouri Medicine, vol. 115, no. 4, 2018, pp. 380–87.

Connor, James R., et al. “Iron and Restless Legs Syndrome: Treatment, Genetics and Pathophysiology.” Sleep Medicine, vol. 31, 2017, pp. 61–70. PubMed, doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2016.07.028.

England, Sandra J., et al. “L-Dopa Improves Restless Legs Syndrome and Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep but Not Attention-Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder in a Double-Blind Trial in Children.” Sleep Medicine, vol. 12, no. 5, May 2011, pp. 471–77. PubMed, doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2011.01.008.

García-Martín, Elena, et al. “Missense Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Receptor Polymorphisms Are Associated with Reaction Time, Motor Time, and Ethanol Effects in Vivo.” Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, vol. 12, Jan. 2018. PubMed Central, doi:10.3389/fncel.2018.00010.

Haba-Rubio, José, et al. “Prevalence and Determinants of Periodic Limb Movements in the General Population.” Annals of Neurology, vol. 79, no. 3, Mar. 2016, pp. 464–74. PubMed, doi:10.1002/ana.24593.

Hornyak, M., et al. “Magnesium Therapy for Periodic Leg Movements-Related Insomnia and Restless Legs Syndrome: An Open Pilot Study.” Sleep, vol. 21, no. 5, Aug. 1998, pp. 501–05. PubMed, doi:10.1093/sleep/21.5.501.

Innes, Kim E., et al. “Efficacy of an Eight-Week Yoga Intervention on Symptoms of Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS): A Pilot Study.” Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine (New York, N.Y.), vol. 19, no. 6, June 2013, pp. 527–35. PubMed, doi:10.1089/acm.2012.0330.

Jiménez-Jiménez, Félix Javier, et al. “Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Receptors Genes Polymorphisms and Risk for Restless Legs Syndrome.” The Pharmacogenomics Journal, vol. 18, no. 4, 2018, pp. 565–77. PubMed, doi:10.1038/s41397-018-0023-7.

—. “Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Receptors Genes Polymorphisms and Risk for Restless Legs Syndrome.” The Pharmacogenomics Journal, vol. 18, no. 4, 2018, pp. 565–77. PubMed, doi:10.1038/s41397-018-0023-7.

Kemlink, D., et al. “Replication of Restless Legs Syndrome Loci in Three European Populations.” Journal of Medical Genetics, vol. 46, no. 5, May 2009, pp. 315–18. PubMed, doi:10.1136/jmg.2008.062992.

Kim, Min Seung, et al. “Impaired Endothelial Function May Predict Treatment Response in Restless Legs Syndrome.” Journal of Neural Transmission (Vienna, Austria: 1996), vol. 126, no. 8, Aug. 2019, pp. 1051–59. PubMed, doi:10.1007/s00702-019-02031-x.

Lamberti, Nicola, et al. “Restless Leg Syndrome in Peripheral Artery Disease: Prevalence among Patients with Claudication and Benefits from Low-Intensity Exercise.” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 8, no. 9, Sept. 2019. PubMed Central, doi:10.3390/jcm8091403.

Lyu, Shangru, et al. “The Role of BTBD9 in Striatum and Restless Legs Syndrome.” ENeuro, vol. 6, no. 5, Oct. 2019. PubMed Central, doi:10.1523/ENEURO.0277-19.2019.

Mitchell, Ulrike H., et al. “Decreased Symptoms without Augmented Skin Blood Flow in Subjects with RLS/WED after Vibration Treatment.” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine: JCSM: Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, vol. 12, no. 7, 15 2016, pp. 947–52. PubMed, doi:10.5664/jcsm.5920.

Moore, Hyatt, et al. “Periodic Leg Movements during Sleep Are Associated with Polymorphisms in BTBD9, TOX3/BC034767, MEIS1, MAP2K5/SKOR1, and PTPRD.” Sleep, vol. 37, no. 9, Sept. 2014, pp. 1535–42. PubMed Central, doi:10.5665/sleep.4006.

—. “Periodic Leg Movements during Sleep Are Associated with Polymorphisms in BTBD9, TOX3/BC034767, MEIS1, MAP2K5/SKOR1, and PTPRD.” Sleep, vol. 37, no. 9, Sept. 2014, pp. 1535–42. PubMed Central, doi:10.5665/sleep.4006.

—. “Periodic Leg Movements during Sleep Are Associated with Polymorphisms in BTBD9, TOX3/BC034767, MEIS1, MAP2K5/SKOR1, and PTPRD.” Sleep, vol. 37, no. 9, Sept. 2014, pp. 1535–42. PubMed, doi:10.5665/sleep.4006.

—. “Periodic Leg Movements during Sleep Are Associated with Polymorphisms in BTBD9, TOX3/BC034767, MEIS1, MAP2K5/SKOR1, and PTPRD.” Sleep, vol. 37, no. 9, Sept. 2014, pp. 1535–42. PubMed Central, doi:10.5665/sleep.4006.

Raissi, Gholam Reza, et al. “Evaluation of Acupuncture in the Treatment of Restless Legs Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian Studies, vol. 10, no. 5, Oct. 2017, pp. 346–50. PubMed, doi:10.1016/j.jams.2017.08.004.

Rizzo, Giovanni, et al. “Brain Imaging and Networks in Restless Legs Syndrome.” Sleep Medicine, vol. 31, Mar. 2017, pp. 39–48. PubMed Central, doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2016.07.018.

Sarayloo, Faezeh, et al. “MEIS1 and Restless Legs Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review.” Frontiers in Neurology, vol. 10, Aug. 2019. PubMed Central, doi:10.3389/fneur.2019.00935.

—. “MEIS1 and Restless Legs Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review.” Frontiers in Neurology, vol. 10, Aug. 2019. PubMed Central, doi:10.3389/fneur.2019.00935.

—. “MEIS1 and Restless Legs Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review.” Frontiers in Neurology, vol. 10, Aug. 2019. PubMed Central, doi:10.3389/fneur.2019.00935.

Song, Yuan-Yuan, et al. “Effects of Exercise Training on Restless Legs Syndrome, Depression, Sleep Quality, and Fatigue Among Hemodialysis Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, vol. 55, no. 4, 2018, pp. 1184–95. PubMed, doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.12.472.

Stefani, Ambra, et al. “Influence of High Altitude on Periodic Leg Movements during Sleep in Individuals with Restless Legs Syndrome and Healthy Controls: A Pilot Study.” Sleep Medicine, vol. 29, Jan. 2017, pp. 88–89. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2016.06.037.

Stefansson, Hreinn, et al. “A Genetic Risk Factor for Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 357, no. 7, Aug. 2007, pp. 639–47. PubMed, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa072743.

—. “A Genetic Risk Factor for Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 357, no. 7, Aug. 2007, pp. 639–47. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa072743.

Thireau, Jérôme, et al. “MEIS1 Variant as a Determinant of Autonomic Imbalance in Restless Legs Syndrome.” Scientific Reports, vol. 7, 20 2017, p. 46620. PubMed, doi:10.1038/srep46620.

Trenkwalder, C., et al. “L-Dopa Therapy of Uremic and Idiopathic Restless Legs Syndrome: A Double-Blind, Crossover Trial.” Sleep, vol. 18, no. 8, Oct. 1995, pp. 681–88. PubMed, doi:10.1093/sleep/18.8.681.

Winkelmann, Juliane, et al. “Genome-Wide Association Study of Restless Legs Syndrome Identifies Common Variants in Three Genomic Regions.” Nature Genetics, vol. 39, no. 8, Aug. 2007, pp. 1000–06. PubMed, doi:10.1038/ng2099.

Xiong, Lan, et al. “MEIS1 Intronic Risk Haplotype Associated with Restless Legs Syndrome Affects Its MRNA and Protein Expression Levels.” Human Molecular Genetics, vol. 18, no. 6, Mar. 2009, pp. 1065–74. PubMed Central, doi:10.1093/hmg/ddn443.

Yang, Qinbo, et al. “Family-Based and Population-Based Association Studies Validate PTPRD as a Risk Factor for Restless Legs Syndrome.” Movement Disorders : Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society, vol. 26, no. 3, Feb. 2011, pp. 516–19. PubMed Central, doi:10.1002/mds.23459.