Key takeaways:

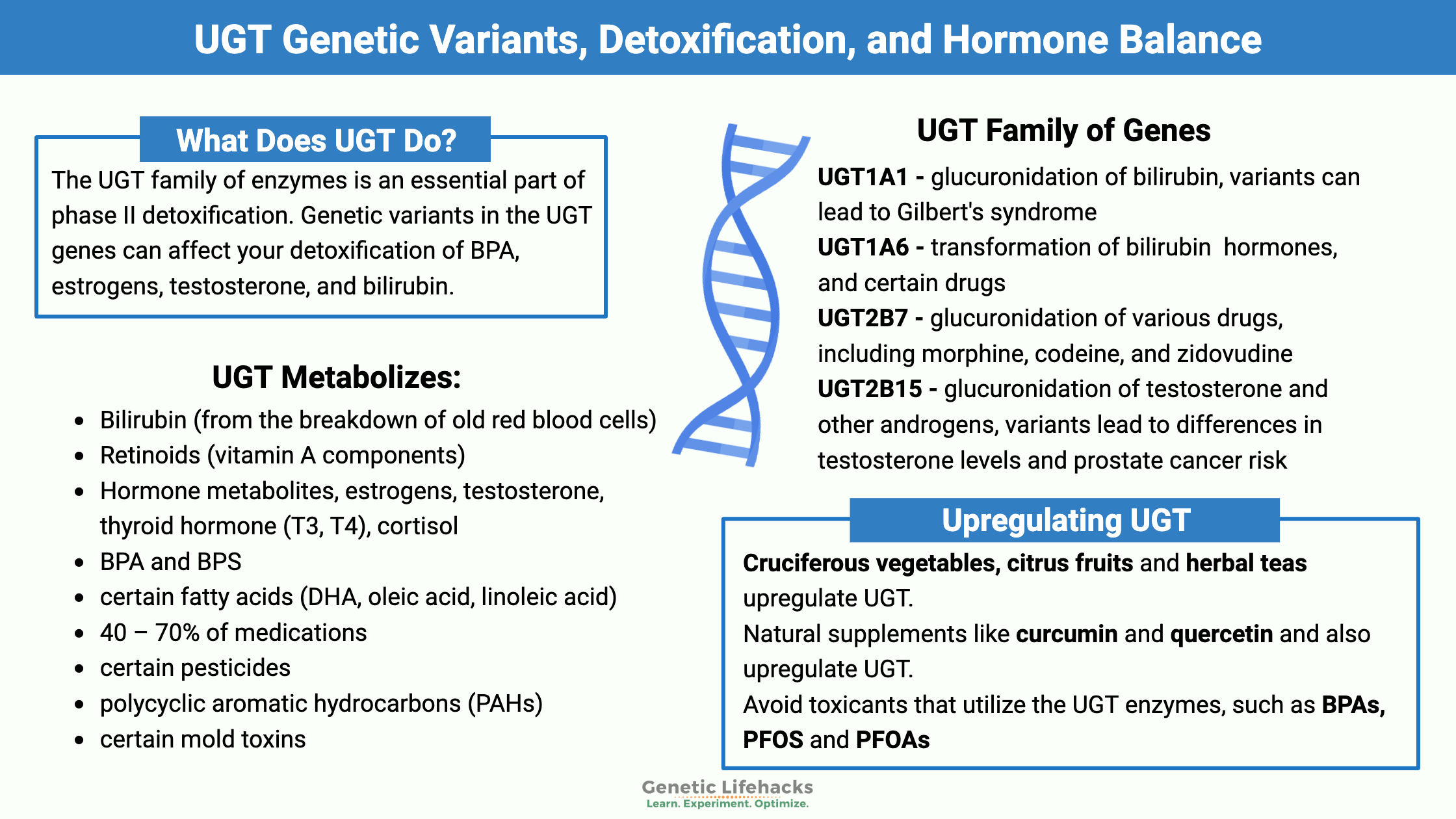

~ The UGT family of enzymes is an essential part of phase II detoxification.

~ Genetic variants in the UGT genes can affect your detoxification of BPA, estrogens, testosterone, and bilirubin.

~ Certain foods, like cruciferous vegetables, or supplements can upregulate this pathway.

The UGT family of enzymes is responsible for an important part of phase II detoxification. In this article, I’ll explain what the UGT enzymes do in the body, how your genes impact this part of detoxification, and lifestyle factors that can increase or decrease this detox process.

Members will see their UGT genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Join today.

Glucuronidation, phase II detoxification:

Listen to this article:

When foreign substances enter the body, such as toxicants or prescription medications, the body breaks them down and eliminates them in a two-step process called phase I and phase II detoxification. Phase I detoxification uses the CYP450 enzymes to make the substance more polar. Then in phase II, the toxic substance is altered again to make it water-soluble so that it can be easily excreted from the body.

Overview: Detoxification: Phase I and Phase II Metabolism

Phase II detoxification is where the UGT genes come into play.

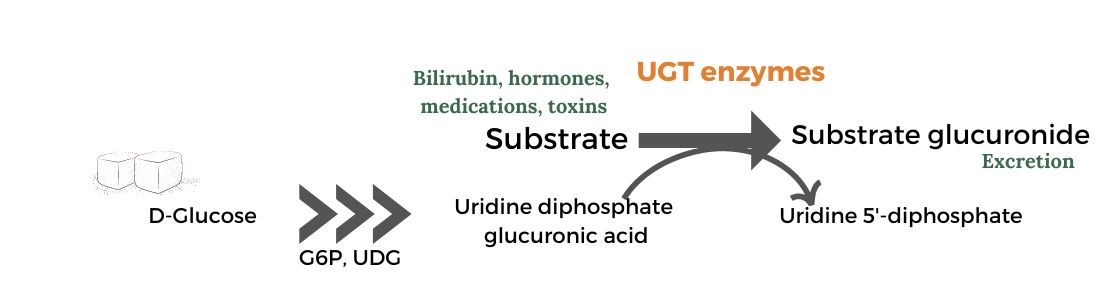

The UGT (UDP-glucuronosyltransferase) enzymes facilitate a glucuronidation reaction. Glucuronidation helps make certain toxic substances more water-soluble and able to be excreted through urine or feces.

This is important because the phase I detoxification metabolites are often more toxic and can cause oxidative stress or DNA damage. You don’t want the phase I metabolites hanging around, damaging cells or DNA. Thus, this phase II glucuronidation process needs to act in sync with phase I, making the substance water-soluble and quickly eliminated.

Glucuronidation involves the attachment of a glucuronic acid molecule to a toxicant or drug metabolite. Glucuronic acid is a metabolite of glucose and is abundant in the body.

The enzymes responsible for this process are called UDP-glucuronosyltransferases, or UGTs for short.

toxic metabolite + glucuronic acid + UGT enzyme = non-toxic, excretable

Where does glucuronidation occur?

Glucuronidation reactions are used by the body to inactivate and eliminate:

- Bilirubin (from the breakdown of old red blood cells)

- Retinoids (vitamin A components)

- Hormone metabolites:

- BPA and BPS[ref][ref]

- certain fatty acids (DHA, oleic acid, linoleic acid)[ref]

- 40 – 70% of medications[ref], including acetaminophen (Tylenol)[ref]

- certain pesticides[ref]

- polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs, carcinogenic)[ref]

- certain mold toxins[ref]

There are many different genetic variants in the UGT family of enzymes. Thus, some people may be more sensitive to certain medications or have a harder time breaking down and eliminating substances, such as BPA or mold toxins.

What are the UGT genes?

There are 20 UGT genes that encode different UGT enzymes, each with its own specific substrates and functions.[ref] Some of the most well-studied UGT genes include:

UGT1A1: This gene is responsible for the glucuronidation of bilirubin, a breakdown product of red blood cells. Variants in UGT1A1 can lead to Gilbert’s syndrome, a condition characterized by mildly elevated bilirubin levels. UGT1A1 also plays a role in the metabolism of certain drugs, such as irinotecan, a chemotherapy agent.

Gilbert’s Syndrome involves bilirubin not being broken down appropriately.[ref] This syndrome leads to periodic increases in the level of unconjugated bilirubin, especially in times of physical stress such as illness, intense exercise, or fasting. This is a fairly common disorder with symptoms that include periodic yellowing of the eyes, abdominal pain, and fatigue.

Related article: Gilbert’s Syndrome

UGT1A6: This enzyme helps with transforming bilirubin, hormones, and certain drugs (aspirin, acetaminophen) into water-soluble metabolites for excretion. Studies on this gene also look at the variants in association with benzene poisoning. Genetic variations in UGT1A6 may influence an individual’s risk of acetaminophen-induced liver toxicity and the effectiveness of certain NSAIDs.

UGT2B7: This enzyme is involved in the glucuronidation of various drugs, including morphine, codeine, and zidovudine (an HIV medication). Genetic variants in UGT2B7 can affect an individual’s response to these medications.[ref]

UGT2B15: This gene is responsible for the glucuronidation of testosterone and other androgens. Variants in UGT2B15 have been associated with differences in testosterone levels and prostate cancer risk.[ref] UGT2B15 is also involved in the metabolism of tamoxifen.[ref]

BPA is also eliminated, in part, using glucuronidation. One study found that UGT2B15 metabolizes up to 80% of BPA when concentrations are low, such as our normal daily exposure, but that another enzyme (UGT1A9) becomes more important at higher BPA levels.[ref]

It’s important to note that while genetic variants influence glucuronidation, other factors such as age, sex, diet, and liver function also play significant roles.

Odor detection, COVID loss of smell, and the UGT genes:

Interestingly, the UGT genes also interact with odor molecules in the nose. The UGT enzymes are expressed in the cells lining the nose. When an odor molecule is glucuronidated (using a UGT enzyme), it no longer activates odor receptors, thus turning off the signal to the brain that you smell something. This ‘turning off’ of the smell means that things you smell are more transient – instead of a constant signal that lasts for a long time. Something we can be grateful for when it comes to bad odors!

Why is this so interesting?

New research shows that the inability to smell things (anosmia) as a result of Covid may be linked with genetic variants in the UGT genes. While the difference based on the specific SNP identified in the study isn’t big (11% increased relative risk of anosmia), the mechanism of action indicated by the genetic findings is interesting. And no, the SNP identified in the study is not in 23andMe or AncestryDNA data.[ref]

UGT Genotype Report:

Members: Log in to see your data below.

Not a member? Join here.

Why is this section is now only for members? Here’s why…

Lifehacks: Natural solutions for slow UGTs

If your genetic data shows that you have slower than normal UGT activity, you may want to look into the following:

Upregulating glucuronidation and the UGT enzymes:

Related Articles and Topics:

Gilbert’s Syndrome:

Variants in the UGT genes cause higher bilirubin levels. Learn all about Gilbert’s syndrome here.

How your genes influence BPA detoxification:

BPA, a chemical found in some plastics, has been linked to a variety of effects on people, including obesity, insulin resistance, and epigenetic effects on the fetus. Genetics plays a role in how quickly you can eliminate BPA from your body.

Nrf2 Pathway: Increasing the body’s ability to get rid of toxins

The Nrf2 (Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor) signaling pathway regulates the expression of antioxidants and phase II detoxification enzymes. This is a fundamental pathway that is important in how well your body functions. Your genetic variants impact how well this pathway functions.

Phase I and Phase II detoxification

Learn how the different genetic variants in phase I and phase II detoxification genes impact the way that you react to medications and break down different toxins.

References:

Bale, Govardhan, et al. “Incidence and Risk of Gallstone Disease in Gilbert’s Syndrome Patients in Indian Population.” Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hepatology, vol. 8, no. 4, Dec. 2018, pp. 362–66. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jceh.2017.12.006.

Buch, Stephan, et al. “Loci from a Genome-Wide Analysis of Bilirubin Levels Are Associated with Gallstone Risk and Composition.” Gastroenterology, vol. 139, no. 6, Dec. 2010, pp. 1942-1951.e2. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.003.

—. “Loci from a Genome-Wide Analysis of Bilirubin Levels Are Associated with Gallstone Risk and Composition.” Gastroenterology, vol. 139, no. 6, Dec. 2010, pp. 1942-1951.e2. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.003.

Court, Michael H., et al. “The UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A Polymorphism c.2042C>G (Rs8330) Is Associated with Increased Human Liver Acetaminophen Glucuronidation, Increased UGT1A Exon 5a/5b Splice Variant MRNA Ratio, and Decreased Risk of Unintentional Acetaminophen-Induced Acute Liver Failure.” The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, vol. 345, no. 2, May 2013, pp. 297–307. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.112.202010.

Desrouillères, Kerlynn, et al. “Cancer Preventive Effect of a Specific Probiotic Fermented Milk Components and Cell Walls Extracted from a Biomass Containing L. Acidophilus CL1285, L. Casei LBC80R, and L. Rhamnosus CLR2 on Male F344 Rats Treated with 1,2-Dimethylhydrazine.” Journal of Functional Foods, vol. 26, Oct. 2016, pp. 373–84. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2016.08.005.

Dwivedi, Chandradhar, et al. “Effect of Calcium Glucarate on β-Glucuronidase Activity and Glucarate Content of Certain Vegetables and Fruits.” Biochemical Medicine and Metabolic Biology, vol. 43, no. 2, Apr. 1990, pp. 83–92. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/0885-4505(90)90012-P.

Franco, Marco E., et al. “Altered Expression and Activity of Phase I and II Biotransformation Enzymes in Human Liver Cells by Perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS).” Toxicology, vol. 430, Jan. 2020, p. 152339. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2019.152339.

Gilbert Syndrome: MedlinePlus Genetics. https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/gilbert-syndrome/. Accessed 20 Sept. 2021.

Girard, Hugo, et al. “The Novel Ugt1a9 Intronic I399 Polymorphism Appears as a Predictor of 7-Ethyl-10-Hydroxycamptothecin Glucuronidation Levels in the Liver.” Drug Metabolism and Disposition, vol. 34, no. 7, July 2006, pp. 1220–28. dmd.aspetjournals.org, https://doi.org/10.1124/dmd.106.009787.

Gramec Skledar, Darja, et al. “Differences in the Glucuronidation of Bisphenols F and S between Two Homologous Human UGT Enzymes, 1A9 and 1A10.” Xenobiotica; the Fate of Foreign Compounds in Biological Systems, vol. 45, no. 6, 2015, pp. 511–19. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3109/00498254.2014.999140.

Hodgson, Ernest. “Chapter 4 – Introduction to Biotransformation (Metabolism).” Pesticide Biotransformation and Disposition, edited by Ernest Hodgson, Academic Press, 2012, pp. 53–72. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-385481-0.00004-6.

Kawee-Ai, Arthitaya, and Sang Moo Kim. “Application of Microalgal Fucoxanthin for the Reduction of Colon Cancer Risk: Inhibitory Activity of Fucoxanthin against Beta-Glucuronidase and DLD-1 Cancer Cells.” Natural Product Communications, vol. 9, no. 7, July 2014, pp. 921–24.

Konaka, Ken, et al. “Study on the Optimal Dose of Irinotecan for Patients with Heterozygous Uridine Diphosphate-Glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1).” Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin, vol. 42, no. 11, 2019, pp. 1839–45. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1248/bpb.b19-00357.

Kuo, Sung-Hsin, et al. “Polymorphisms of ESR1, UGT1A1, HCN1, MAP3K1 and CYP2B6 Are Associated with the Prognosis of Hormone Receptor-Positive Early Breast Cancer.” Oncotarget, vol. 8, no. 13, Mar. 2017, pp. 20925–38. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.14995.

Kuypers, Dirk R. J., et al. “The Impact of Uridine Diphosphate–Glucuronosyltransferase 1A9 (UGT1A9) Gene Promoter Region Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms T—275A and C—2152T on Early Mycophenolic Acid Dose-Interval Exposure in de Novo Renal Allograft Recipients.” Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, vol. 78, no. 4, 2005, pp. 351–61. Wiley Online Library, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clpt.2005.06.007.

Maekawa, Shinya, et al. “Association between Alanine Aminotransferase Elevation and UGT1A1*6 Polymorphisms in Daclatasvir and Asunaprevir Combination Therapy for Chronic Hepatitis C.” Journal of Gastroenterology, vol. 53, no. 6, June 2018, pp. 780–86. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-017-1405-3.

Maruti, Sonia S., et al. “Serum β-Glucuronidase Activity in Response to Fruit and Vegetable Supplementation: A Controlled Feeding Study.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention : A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, Cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, vol. 17, no. 7, July 2008, pp. 1808–12. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2660.

Mehboob, Huma, et al. “Effect of UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A Polymorphism (Rs8330 and Rs10929303) on Glucuronidation Status of Acetaminophen.” Dose-Response, vol. 15, no. 3, Sept. 2017, p. 1559325817723731. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1177/1559325817723731.

Oussalah, Abderrahim, et al. “Exome-Wide Association Study Identifies New Low-Frequency and Rare UGT1A1 Coding Variants and UGT1A6 Coding Variants Influencing Serum Bilirubin in Elderly Subjects.” Medicine, vol. 94, no. 22, June 2015, p. e925. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000000925.

—. “Exome-Wide Association Study Identifies New Low-Frequency and Rare UGT1A1 Coding Variants and UGT1A6 Coding Variants Influencing Serum Bilirubin in Elderly Subjects: A Strobe Compliant Article.” Medicine, vol. 94, no. 22, June 2015, p. e925. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000000925.

Pollet, Rebecca M., et al. “An Atlas of β-Glucuronidases in the Human Intestinal Microbiome.” Structure (London, England : 1993), vol. 25, no. 7, July 2017, pp. 967-977.e5. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.str.2017.05.003.

Rs4124874 – SNPedia. https://snpedia.com/index.php/Rs4124874. Accessed 20 Sept. 2021.

Russell, W. M., and T. R. Klaenhammer. “Identification and Cloning of GusA, Encoding a New β-Glucuronidase from Lactobacillus Gasseri ADH.” Applied and Environmental Microbiology, vol. 67, no. 3, Mar. 2001, pp. 1253–61. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.67.3.1253-1261.2001.

Shibuya, Ayako, et al. “Impact of Fatty Acids on Human UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 Activity and Its Expression in Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia.” Scientific Reports, vol. 3, Oct. 2013, p. 2903. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02903.

Sten, Taina, et al. “UDP-Glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) 2B7 and UGT2B17 Display Converse Specificity in Testosterone and Epitestosterone Glucuronidation, Whereas UGT2A1 Conjugates Both Androgens Similarly.” Drug Metabolism and Disposition: The Biological Fate of Chemicals, vol. 37, no. 2, Feb. 2009, pp. 417–23. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1124/dmd.108.024844.

Tang, Wei, et al. “Mapping of the UGT1A Locus Identifies an Uncommon Coding Variant That Affects MRNA Expression and Protects from Bladder Cancer.” Human Molecular Genetics, vol. 21, no. 8, Apr. 2012, pp. 1918–30. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddr619.

TSUNEDOMI, RYOUICHI, et al. “A Novel System for Predicting the Toxicity of Irinotecan Based on Statistical Pattern Recognition with UGT1A Genotypes.” International Journal of Oncology, vol. 45, no. 4, July 2014, pp. 1381–90. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2014.2556.

van der Logt, E. M. J., et al. “Induction of Rat Hepatic and Intestinal UDP-Glucuronosyltransferases by Naturally Occurring Dietary Anticarcinogens.” Carcinogenesis, vol. 24, no. 10, Oct. 2003, pp. 1651–56. Silverchair, https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgg117.

Vergara, Ana G., et al. “UDP-Glycosyltransferase 3A Metabolism of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Potential Importance in Aerodigestive Tract Tissues.” Drug Metabolism and Disposition: The Biological Fate of Chemicals, vol. 48, no. 3, Mar. 2020, pp. 160–68. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1124/dmd.119.089284.

Waszkiewicz, Napoleon, et al. “Serum β-Glucuronidase as a Potential Colon Cancer Marker: A Preliminary Study.” Postepy Higieny I Medycyny Doswiadczalnej (Online), vol. 69, Apr. 2015, pp. 436–39. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.5604/17322693.1148704.

Wu, Tien-Yuan, et al. “Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of 3,3’-Diindolylmethane (DIM) in Regulating Gene Expression of Phase II Drug Metabolizing Enzymes.” Journal of Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics, vol. 42, no. 4, Aug. 2015, pp. 401–08. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10928-015-9421-5.

Yang, Guangyi, et al. “Glucuronidation: Driving Factors and Their Impact on Glucuronide Disposition.” Drug Metabolism Reviews, vol. 49, no. 2, May 2017, pp. 105–38. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1080/03602532.2017.1293682.

Zhou, Youyou, et al. “Association of UGT1A1 Variants and Hyperbilirubinemia in Breast-Fed Full-Term Chinese Infants.” PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 8, Aug. 2014, p. e104251. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0104251.

Originally published Jun 3, 2015