Key takeaways:

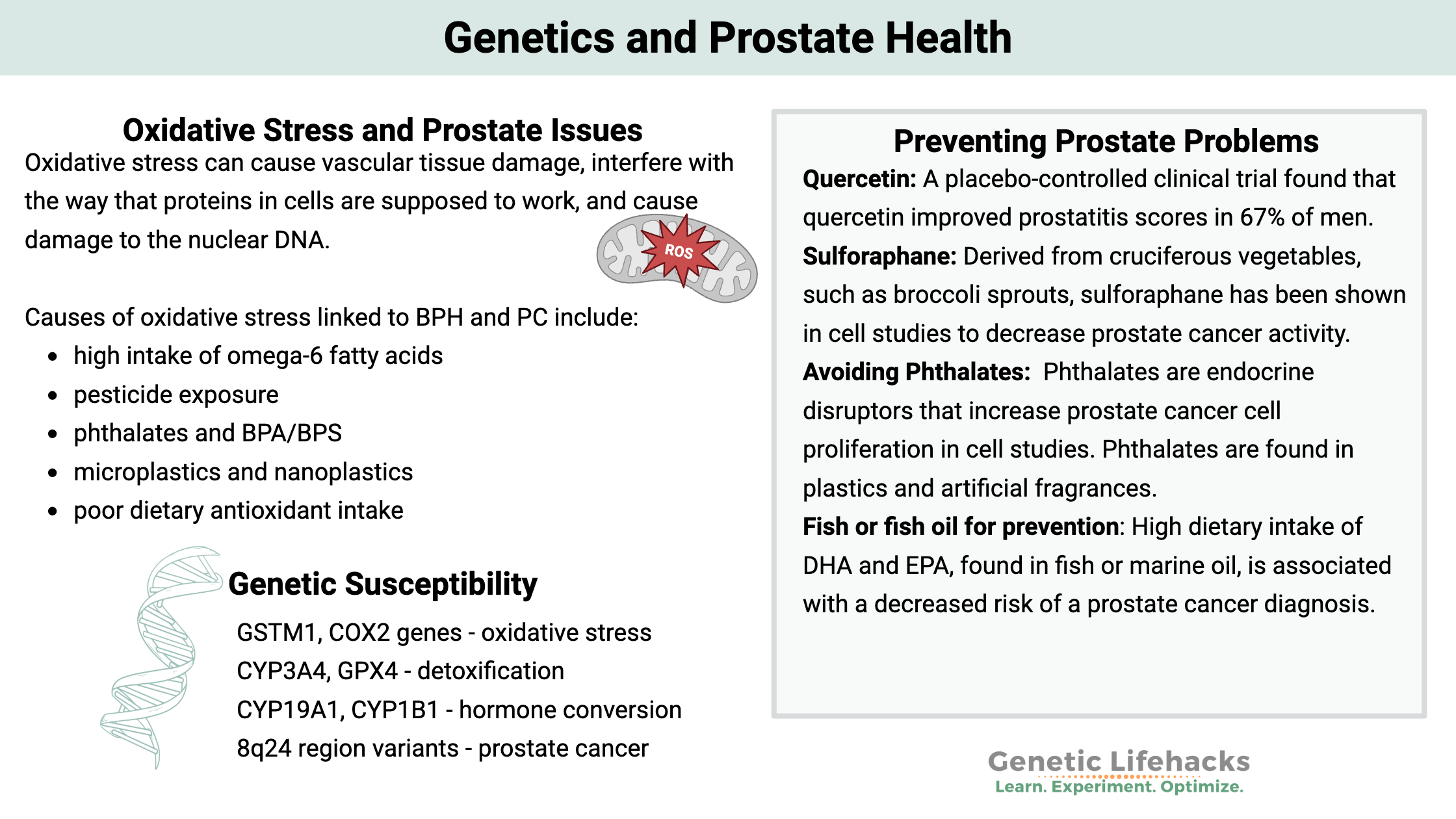

~ Oxidative stress, caused by an imbalance of reactive oxygen species (ROS), is a significant factor in the development of prostate cancer and benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH). It can damage cells, interfere with protein function, and harm DNA.

~ Diet and environmental toxins matter, increasing oxidative stress and inflammation in the prostate, contributing to prostate problems.

~ Genetic variants can increase the risk of BPH or prostate cancer, and some of these variants are related to how our bodies handle environmental toxins.

~ Understanding these genetic factors can help you know which environmental factors and dietary interactions are most important.

Members will see their genotype report below and the solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

What causes prostate problems?

Prostate problems are common in men as they age, with conditions like benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), prostatitis, and prostate cancer affecting millions of men. Your genetic variants, along with environmental factors, significantly influence your risk of developing prostate issues.

In this article, you’ll learn:

- What the prostate does and why problems occur

- The underlying causes of changes and inflammation in the prostate

- Risk factors, including genetic variants and how they combine with environment

- Diet, lifestyle, and supplements that can help prevent problems

Types of prostate problems:

Prostate problems are common in older men and can include:

| Condition | Description | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Prostatitis | Inflammation of the prostate | Pain, urinary symptoms |

| BPH | Benign prostatic hyperplasia (enlarged, non-cancer) | Urinary obstruction, not cancer |

| Prostate Cancer | Malignant growth in prostate | May be slow or aggressive |

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels are used to screen for prostate issues. High PSA levels can indicate prostatitis, BPH, or prostate cancer. The name prostate-specific is a bit of a misnomer since women also produce PSA at lower levels.

Prostate cancer is one of the most common cancers in men. In the US and EU, it is the second most common cancer diagnosis — and the second highest cause of cancer-related deaths in males. (Lung cancer is #1.) Currently, 1 in 8 men can expect to be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their lifetime, but the good news is that the 5-year survival rate is 99% when caught early.[ref][ref]

What does the prostate do?

The prostate is a gland in the male reproductive system that surrounds the urethra just below the bladder. It secretes a part of the fluid that becomes semen and protects sperm. Additionally, it acts as a muscle that is important in controlling urination. When the prostate is enlarged, it can press on the bladder and decrease urine flow through the urethra.

Oxidative stress at the heart of prostate cancer and BPH:

One of the most critical molecular pathways in the development of prostate cancer involves a complex interaction between oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and androgen receptor (AR) driven signaling. Additionally, it has been suggested that oxidative stress is essential for the formation of the aggressive phenotype in addition to being fundamental to prostate cancer growth.

What is oxidative stress?

Oxidative stress is the state in a cell when reactive oxygen species (ROS) are higher than normal. Reactive oxygen species are molecules with free radicals derived from oxygen through redox reactions. Examples of ROS include hydrogen peroxide, superoxide, and hydroxyl radicals. ROS at low levels has important signaling properties within a cell, but a higher levels, ROS is very detrimental.

Oxidative stress can cause vascular tissue damage, interfere with the way that proteins in cells are supposed to work, and cause damage to the nuclear DNA. Oxidative stress can also negatively impact stem cells and decrease a cell’s ability to repair the damage.[ref]

What causes oxidative stress in the prostate?

Oxidative stress increases in aging as well as through exposure to toxicants and dietary choices.

| Factor | Effect on Prostate Health | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Omega-6 fats | ↑ Inflammation, ↑ BPH/PSA | Common in modern diet, fried/packaged foods |

| Pesticide exposure | ↑ Prostate cancer risk (4x in farmers) | Environmental toxin |

| Phthalates, BPA | ↑ Oxidative stress, ↑ BPH/cancer risk | Found in plastics, fragrances |

| Microplastics | ↑ Oxidative stress, found in prostate tissue | May leach endocrine disruptors in addition to ↑ oxidative stress from particles |

| Antioxidant intake | ↓ Risk w/ increased antioxidant intake (e.g., broccoli, fish) | Especially for GSTM1 null genotype |

Let’s take a look at how diet and toxins increase susceptibility to prostate problems…

Oxidative stress from diet:

Omega-6 fats are found in large quantities in our modern diet (fried foods, mayo, chips, sauces, etc.).

The peroxidation of omega-6 fatty acids causes inflammation in the prostate. Men with BPH and high PSA levels have higher levels of these peroxidation metabolites. Our modern diet has a lot higher intake of omega-6 fats than humans have historically eaten. This is likely one of the reasons behind the increase in prostate problems since the 1950s.[ref][ref]

Why is the prostate so vulnerable?

Prostate cells turn over rapidly and have fewer DNA repair enzymes, thus leaving them vulnerable to damage from oxidative stress. This damage then leads to the activation of inflammatory pathways.[ref]

Decreased antioxidants:

In men with BPH, research shows they have a decrease in antioxidant defenses. In other words, the excess of ROS in the prostate can’t be countered by the body’s built-in antioxidant defenses.[ref] This could be due to a lack of micronutrients in the diet or due to continuing exposure to a toxicant that causes oxidative stress.

Age is an important factor:

One reason that aging is associated with oxidative stress is an increase in cellular senescence.

cellular senescence = increased inflammation in the prostate = BPH

Senescent cells are at the end of their cellular life and are unable to divide. This process is normal, and senescent cells are cleared out throughout life. But in older people, there is an increase in senescence above what can be easily cleared out. It is a problem because senescent cells give off inflammatory cytokines (which normally are the signal that causes the immune system to clear them out). An excess of senescent cells then leads to elevated inflammation, which is directly linked in research to the development of BPH.[ref]

~ Oxidative stress is a major driver of BPH and PC

~ Diets high in omega-6 oils and exposure to toxins (pesticides, phthalates, microplastics) increase oxidative stress in the prostate.

~ Cellular senescence and inflammation increase with age, raising the risk.

Environmental toxins:

In addition to dietary causes and cellular senescence in aging, exposure to toxicants also increases oxidative stress in the prostate.

Here are examples from research studies on environmental factors:

- Farmers exposed to high levels of pesticides are at a fourfold increased risk of prostate cancer.[ref]

- Dioxins are persistent organic pollutants that increase the risk of prostate cancer.[ref]

- Phthalates are chemicals found in artificial fragrances (think air fresheners, laundry detergents, and shampoo) and plastics. Phthalates act as endocrine disruptors and are associated with oxidative stress in BPH and prostate cancer.[ref]

- Exposure to trace metals, such as cadmium, mercury, lead, or nickel, is also associated with prostate diseases.[ref]

- BPA, an estrogen mimic found in plastics, is linked to enlarged prostate and prostate cancer risk.[ref][ref]

- PFAS (Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) exposure increases the relative risk of prostate cancer (a little bit).[ref]

There’s a new environmental factor that research is showing to be a significant problem: microplastic and nanoplastic particles.

A 2024 study investigated prostate tumor tissue samples. The results showed that the tumors and tissue around the tumors contained microplastics primarily in the 20 to 50 μm size range, with polystyrene and PVC particles being the main types.[ref]

Another 2024 study of prostate tissue from men undergoing the TUR-P procedure (non-cancerous tissue) showed that 50% of the tissue samples contain microplastic particles.[ref]

Microplastics have also been found in semen and testicular samples. The particles have been shown to directly increase oxidative stress. Additionally, some microplastic particles may leach endocrine disruptors, such as BPA or BPS.[ref]

How do cells take care of oxidative stress?

Cells can respond to excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) with several built-in antioxidant defenses. Essentially, molecules that contain free oxygen are highly reactive.

ROS isn’t completely bad and is utilized by cells in specific ways for cell signaling. However, the level of ROS is tightly controlled in cells. Excess reactive oxygen species (ROS), termed oxidative stress, can lead to cell damage, including DNA damage or cell death.

Cells have multiple ways of controlling the level of ROS, including endogenous antioxidants such as glutathione, superoxide dismutases (SOD), and catalase. Genetic variants related to the ability to counteract oxidative stress increase the risk of BPH and prostate cancer.

One way cells control oxidative stress is through the Nrf2 pathway. Activation of Nrf2 calls up antioxidant response genes, including the glutathione transferase enzyme (GSTs). As part of Phase II detoxification, GSTs are the enzymes responsible for causing the reaction between glutathione and other substances, such as toxicants, to make them water-soluble and able to be easily excreted.[ref]

I’ll come back to these oxidative stress enzymes in the genetics section…

Related article: Nrf2 Pathway: Increasing the body’s ability to get rid of toxins

What causes prostate cancer?

Essentially, cancer is caused by out-of-control cell growth. Mutations or breaks in cellular DNA in specific genes are the driving factors in cancerous cells. The mutations occur either in genes that promote cancer (oncogenes) or in genes that stop cell growth. While mutations happen all the time during DNA replication, we have built-in DNA repair mechanisms that usually catch and correct the mutations. Excessive damage to DNA, such as from genotoxic substances, excess oxidative stress, or radiation, can result in cancer-causing mutations that replicate and result in tumors.[ref]

Commonly, mutations found in prostate cancer cells are in the TP53 (tumor protein p53) gene.[ref] TP53 is a tumor suppressor gene that keeps cells from dividing and growing uncontrolled. Mutations that prevent TP53 from working can then lead to cancer.

Hormones, testosterone, and the prostate:

Let’s dig into how and why hormones impact the prostate.

Androgen hormones are the steroid hormones responsible for male characteristics (lower voice, facial hair, muscle mass, Adam’s apple). Androgens include testosterone, dihydrotestosterone (DHT), Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S). Women also produce these hormones, just at lower levels than men do. Likewise, men produce estrogen, just at much lower levels than women.

Prostate cancer is considered an androgen-dependent cancer, meaning that initial cancer cell proliferation and survival depend on the androgen hormones.

Estrogens, on the other hand, are protective against prostate cancer due to their anti-androgenic effects. Women produce estrogen mainly in the ovaries, but for men, estrogen is created through the conversion of androgen precursors by an enzyme called aromatase. The aromatase enzyme is encoded by the CYP19A1 gene (in the genotype report section), and aromatase is produced in the gonads and prostate.[ref]

Hormones in Cancer vs. BPH:

One difference between benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH) and prostate cancer is the production of aromatase (and thus estrogen) in the prostate cells. Researchers found that in BPH cells, aromatase was produced, creating estrogens from testosterone. But in the prostate cancer biopsies, very little aromatase was present, thus making no detectable estrogens.[ref]

One thing to note here is that circulating levels of androgens and estrogens don’t necessarily show what is happening in the prostate cells. Researchers are finding that the tissue-specific levels of androgens and aromatase in the prostate drive the difference between BPH and prostate cancer.[ref]

Prostate Genotype Report

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Lifehacks:

Everything presented here is for informational purposes only. Talk with your doctor if you have any medical questions or questions about interactions with supplements. Prostate cancer, or BPH, isn’t a DIY healthcare situation.

| Intervention | Evidence/Effect | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Broccoli, sulphoraphane supplements | ↓ Risk, especially for GSTM1 null | Cruciferous vegetables |

| Lycopene (tomatoes) | Mixed evidence, may ↓ PSA, but some ↑ risk | Not universally protective |

| Fish/fish oil | ↓ Risk, especially with COX2 G allele | Omega-3 rich |

| Green tea, coffee | ↓ Risk with polyphenols | Japanese study |

| Quercetin | Improved prostatitis symptoms in clinical trial | Polyphenol supplement |

| Saw Palmetto | Mixed results for BPH | Some studies positive, others not |

| Reishi | Improved BPH symptoms in trial | Mushroom extract |

| Pumpkin seed extract | Relieved urinary symptoms in BPH | Contains sterols |

Dietary changes to prevent prostate problems:

Broccoli for everyone, more broccoli for GSTM1 null:

Access this content:

An active subscription is required to access this content.

Related Articles and Topics:

Testosterone: Genetic Variants that Impact Testosterone Levels

References:

Antczak, Andrzej, et al. “The Variant Allele of the Rs188140481 Polymorphism Confers a Moderate Increase in the Risk of Prostate Cancer in Polish Men.” European Journal of Cancer Prevention: The Official Journal of the European Cancer Prevention Organisation (ECP), vol. 24, no. 2, Mar. 2015, pp. 122–27. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000079.

Apte, Shruti A., et al. “A Low Dietary Ratio of Omega-6 to Omega-3 Fatty Acids May Delay Progression of Prostate Cancer.” Nutrition and Cancer, vol. 65, no. 4, 2013, pp. 556–62. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1080/01635581.2013.775316.

Bangsi, Dieudonne, et al. “Impact of a Genetic Variant in CYP3A4 on Risk and Clinical Presentation of Prostate Cancer among White and African-American Men.” Urologic Oncology, vol. 24, no. 1, Feb. 2006, pp. 21–27. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2005.09.005.

Beuten, Joke, et al. “CYP1B1 Variants Are Associated with Prostate Cancer in Non-Hispanic and Hispanic Caucasians.” Carcinogenesis, vol. 29, no. 9, Sept. 2008, pp. 1751–57. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgm300.

Chang, Wei-Hsiang, et al. “Sex Hormones and Oxidative Stress Mediated Phthalate-Induced Effects in Prostatic Enlargement.” Environment International, vol. 126, May 2019, pp. 184–92. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.02.006.

Chang, Wei-Hsiung, et al. “Oxidative Damage in Patients with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia and Prostate Cancer Co-Exposed to Phthalates and to Trace Elements.” Environment International, vol. 121, no. Pt 2, Dec. 2018, pp. 1179–84. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2018.10.034.

Cheng, Iona, et al. “8q24 and Prostate Cancer: Association with Advanced Disease and Meta-Analysis.” European Journal of Human Genetics: EJHG, vol. 16, no. 4, Apr. 2008, pp. 496–505. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201959.

Dragovic, Sanja, et al. “Effect of Human Glutathione S-Transferase HGSTP1-1 Polymorphism on the Detoxification of Reactive Metabolites of Clozapine, Diclofenac and Acetaminophen.” Toxicology Letters, vol. 224, no. 2, Jan. 2014, pp. 272–81. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.10.023.

Duggan, David, et al. “Two Genome-Wide Association Studies of Aggressive Prostate Cancer Implicate Putative Prostate Tumor Suppressor Gene DAB2IP.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 99, no. 24, Dec. 2007, pp. 1836–44. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djm250.

Grin, Boris, et al. “A Rare 8q24 Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) Predisposes North American Men to Prostate Cancer and Possibly More Aggressive Disease.” BJU International, vol. 115, no. 1, Jan. 2015, pp. 101–05. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.12847.

GSTM1 Glutathione S-Transferase Mu 1 [Homo Sapiens (Human)] – Gene – NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene?cmd=Retrieve&dopt=full_report&list_uids=2944. Accessed 14 July 2022.

Gudmundsson, Julius, et al. “A Study Based on Whole-Genome Sequencing Yields a Rare Variant at 8q24 Associated with Prostate Cancer.” Nature Genetics, vol. 44, no. 12, Dec. 2012, pp. 1326–29. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2437.

Hedelin, Maria, Ellen T. Chang, et al. “Association of Frequent Consumption of Fatty Fish with Prostate Cancer Risk Is Modified by COX-2 Polymorphism.” International Journal of Cancer, vol. 120, no. 2, Jan. 2007, pp. 398–405. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.22319.

Hedelin, Maria, Katarina Augustsson Bälter, et al. “Dietary Intake of Phytoestrogens, Estrogen Receptor-Beta Polymorphisms and the Risk of Prostate Cancer.” The Prostate, vol. 66, no. 14, Oct. 2006, pp. 1512–20. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.20487.

Javed, Saqib, and Stephen E. M. Langley. “Importance of HOX Genes in Normal Prostate Gland Formation, Prostate Cancer Development and Its Early Detection.” BJU International, vol. 113, no. 4, Apr. 2014, pp. 535–40. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.12269.

Kabir, Ali, et al. “Dioxin Exposure in the Manufacture of Pesticide Production as a Risk Factor for Death from Prostate Cancer: A Meta-Analysis.” Iranian Journal of Public Health, vol. 47, no. 2, Feb. 2018, pp. 148–55.

Levin, Albert M., et al. “Chromosome 17q12 Variants Contribute to Risk of Early-Onset Prostate Cancer.” Cancer Research, vol. 68, no. 16, Aug. 2008, pp. 6492–95. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0348.

Minciullo, Paola Lucia, et al. “Oxidative Stress in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: A Systematic Review.” Urologia Internationalis, vol. 94, no. 3, 2015, pp. 249–54. www.karger.com, https://doi.org/10.1159/000366210.

Ragin, Camille, et al. “Farming, Reported Pesticide Use, and Prostate Cancer.” American Journal of Men’s Health, vol. 7, no. 2, Mar. 2013, pp. 102–09. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988312458792.

Severi, Gianluca, et al. “The Common Variant Rs1447295 on Chromosome 8q24 and Prostate Cancer Risk: Results from an Australian Population-Based Case-Control Study.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, Cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, vol. 16, no. 3, Mar. 2007, pp. 610–12. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0872.

Stevens, Victoria L., et al. “HNF1B and JAZF1 Genes, Diabetes, and Prostate Cancer Risk.” The Prostate, vol. 70, no. 6, May 2010, pp. 601–07. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.21094.

Van Blarigan, Erin L., et al. “Plasma Antioxidants, Genetic Variation in SOD2, CAT, GPX1, GPX4, and Prostate Cancer Survival.” Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, Cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, vol. 23, no. 6, June 2014, pp. 1037–46. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0670.

Vital, Paz, et al. “The Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype Promotes Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia.” The American Journal of Pathology, vol. 184, no. 3, Mar. 2014, pp. 721–31. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.11.015.

Wei, Jun, et al. “Germline HOXB13 G84E Mutation Carriers and Risk to Twenty Common Types of Cancer: Results from the UK Biobank.” British Journal of Cancer, vol. 123, no. 9, Oct. 2020, pp. 1356–59. www.nature.com, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-01036-8.

Xu, Bin, et al. “FGFR4 Gly388Arg Polymorphism Contributes to Prostate Cancer Development and Progression: A Meta-Analysis of 2618 Cases and 2305 Controls.” BMC Cancer, vol. 11, Feb. 2011, p. 84. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-11-84.

Xu, Jianfeng, et al. “Inherited Genetic Variant Predisposes to Aggressive but Not Indolent Prostate Cancer.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 107, no. 5, Feb. 2010, pp. 2136–40. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0914061107.

Xu, Zongli, et al. “GWAS SNP Replication among African American and European American Men in the North Carolina-Louisiana Prostate Cancer Project (PCaP).” The Prostate, vol. 71, no. 8, June 2011, pp. 881–91. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.21304.

Zhang, Yixiang, et al. “Association between GSTP1 Ile105Val Polymorphism and Urinary System Cancer Risk: Evidence from 51 Studies.” OncoTargets and Therapy, vol. 9, 2016, pp. 3565–69. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S106527.

Zheng, S. Lilly, et al. “Cumulative Association of Five Genetic Variants with Prostate Cancer.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 358, no. 9, Feb. 2008, pp. 910–19. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa075819.

Zhou, Tian-Biao, et al. “GSTT1 Polymorphism and the Risk of Developing Prostate Cancer.” American Journal of Epidemiology, vol. 180, no. 1, July 2014, pp. 1–10. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwu112.