Key takeaways:

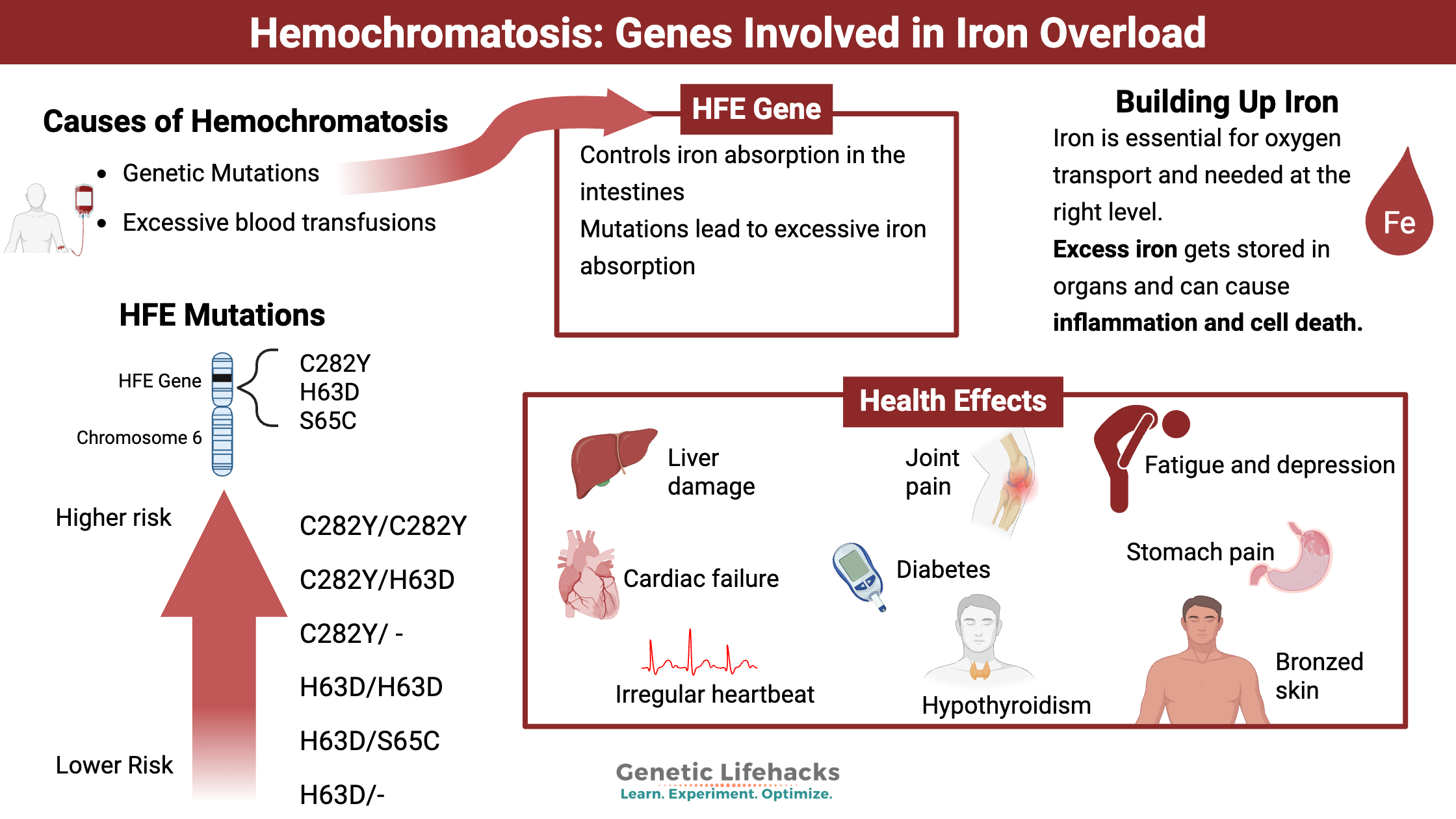

~ Hemochromatosis is a relatively common genetic disease that causes iron to build up in the body, damaging organs and cells which leads to chronic diseases and eventually death.

~ Knowing that you carry the genetic variants for hemochromatosis means that you can prevent iron buildup by giving blood.

~ 23andMe and AncestryDNA genetic data can tell you if you likely carry the more common genetic mutations in the HFE gene for hemochromatosis.

What is hemochromatosis?

Hemochromatosis is the disease state of building up too much iron in the body. It can be caused by genetic mutations in iron-related genes, or it can be due to excessive blood transfusions for anemia or liver disease.

Iron is essential – but it needs to be in just the right amount. People with hereditary hemochromatosis absorb more iron from food than they should due to genetic variants.

Once iron gets absorbed in the intestines, the body doesn’t have a good way to get rid of it. Usually, the body tightly regulates the amount of iron absorbed. When too much iron is absorbed, such as for people carrying genetic variants that cause hemochromatosis, the excess builds up over time. The body stores the excess iron in the organs, including the liver, heart, pancreas, skin, pituitary, and thyroid. You also can store iron in your joints and bone marrow.[ref]

What are the symptoms of hemochromatosis?

Symptoms of building up too much iron can include:

- joint pain

- tiredness

- abdominal pain

- liver disease

- diabetes

- irregular heartbeat

- bronzed skin color

- hypothyroidism

- elevated blood sugar, and more.

Why do we need iron?

The body uses iron in numerous ways. In fact, every cell in the body uses iron in one form or another. Iron, involved in redox reactions, moves electrons in the mitochondria to produce energy. Also, red blood cells need iron as a critical component for moving oxygen throughout the body.

Rusty old iron parts may come to mind when you think about iron out in nature. Rust forms because iron can be easily oxidized, forming compounds with oxygen. This ability to move electrons around makes iron incredibly important and incredibly reactive in the body.

Regulating Iron in the Body:

The body regulates the absorption of iron tightly. We do not want too much oxidation occurring in the wrong place (no ‘rusting’ in the body ;-), but our body also regulates iron to keep it away from iron-loving bacteria. Certain pathogenic species of bacteria thrive and multiply rapidly when iron is available. Thus, we don’t want too much iron in the body, and we have ways of quickly sequestering, or storing, the iron when the body is fighting off a pathogen.[ref]

The liver produces the iron regulatory hormone called hepcidin. Discovered and named in 2000, scientists have since figured out that hepcidin controls the regulation of iron in the body and responds to lipopolysaccharides, a component of bacteria, to prevent iron-loving bacteria from reproducing rapidly.[ref]

The HFE gene was discovered in 1996 and is linked to hereditary hemochromatosis. This gene codes for a protein that controls how iron is taken into the intestinal cells. Free iron is bound to transferrin, which binds to a transferrin receptor to be taken into the cell. HFE can also bind to the transferrin receptor, blocking the receptor from taking iron into the cells. In this way, HFE is a negative regulator of iron absorption.[ref] As an iron sensor, HFE controls iron intake and regulates the downstream production of hepcidin.[ref]

When too much iron is absorbed, whether because of a mutation in the HFE gene or other genes regulating iron, the body stores it in different organs. Excess iron causes oxidative stress and DNA damage to the tissue. This excess can cause fibrosis and cell death, leading to liver cirrhosis or other organ damage.[ref]

How do you inherit hemochromatosis?

There are multiple causes of hereditary hemochromatosis. The most common cause is a genetic variant that impacts the HFE gene. It allows too much iron to be absorbed into the body and is called type 1, or classic hemochromatosis.

Other rare causes of hemochromatosis include variations in other genes involved in hepcidin regulation and iron transport. These are known as hemochromatosis types 2, 3, and 4.

Interestingly, hemochromatosis was first described in the 1700s as ‘bronze diabetes’ or ‘pigmented cirrhosis. It refers to how iron accumulates in the skin and can make it look bronzed, along with the damage to the pancreas causing diabetes or the liver causing cirrhosis.[ref]

How rare is hemochromatosis?

The HFE mutations are much more common in people of Northern European heritage. But, not everyone who carries the variants will end up with a diagnosis of hemochromatosis.

Estimates show that ~10% of people of Northern European ancestry carry one copy of an HFE variant (more on this below). It is thought that the primary hemochromatosis mutation (HFE C282Y) originated in the Celtic or Viking population before 4,000 BC. From there, it spread through the European population.[ref]

Studies on hemochromatosis vary quite a bit in their estimates of how common hemochromatosis is among people with the variants, mainly due to differences in the clinical definition.

Some define hemochromatosis as having a ferritin (a measure of storage iron) level of over 1,000 mcg/l, liver disease, heart failure, and bronzed skin. Others define hemochromatosis as having elevated ferritin (>300 mcg/l) and liver failure.[ref]

The question, then, is at which point in the spectrum of organ damage do physicians define hemochromatosis – is just having the pancreas damaged and causing diabetes enough, or do you also need liver damage? Clinical diagnosis and research study definitions vary quite a bit.

But this website is all about optimizing health, so let’s look at what happens to the body before your liver fails…

Problems with excess iron well before a hemochromatosis diagnosis:

As you can imagine, the symptoms of iron building up can occur over the decades leading up to the point of organ failure.

Symptoms of excess iron include:

Joint pain, fatigue, and irritability are common complaints in people with HFE genetic variants.

Common diagnoses prior to learning about hemochromatosis include fibromyalgia and arthritis.[ref][ref]

Reduced libido and erectile dysfunction in men are common with iron buildup. [ref]

Diabetes and heart disease diagnoses can often precede the clinical diagnosis of hemochromatosis.[ref]

The key here is that all health problems related to excess iron can be prevented.

You aren’t destined to have aches and pains leading up to liver failure or diabetes — knowledge is power here, and iron levels can be reduced. (More on this in the Lifehacks section below).

HFE and the Immune System:

While iron is essential for transporting oxygen throughout the body, it also can be essential for bacterial growth. As I mentioned above, many bacterial species thrive in iron-rich environments. One major role of iron regulation in the body is iron storage via ferritin to sequester iron away from bacteria.[ref] A 2024 study of over 140,000 Danish people found that those who carried the C282Y variant associated with hemochromatosis were at an increased risk of infection, sepsis, and death from infection. The study noted that even those who carried the C282Y variant but had normal iron levels were at an increased risk of infection. [ref]

While iron regulation and the HFE gene are important in bacterial infections, it turns out that HFE may play a role in the immune system that is not related to iron. In fact, researchers initially classified the HFE gene as part of the HLA system[ref]

Research shows that a protein in HIV significantly downregulates the HFE (iron homeostasis) gene.[ref] Researchers have also found that infection with cytomegalovirus also decreases HFE by degrading the protein.

The question for researchers has been, ‘How does interfering with iron and downregulating the HFE protein help viruses reproduce?’.

It turns out that the answer may be that HFE plays a role in the innate immune response that is separate from iron homeostasis. Recent research shows that irrespective of iron levels, HFE interacts with interferon, which is the body’s initial fighter against viral infections. HFE deficiency (in mice) increased interferon and made the animals more resistant to the flu virus.[ref]

The benefit of an HFE mutation?

The negative impacts of too much iron are obvious.

Researchers hypothesize that HFE mutations are relatively common in the population due to a survival benefit. Women with higher iron levels would be less likely to die in childbirth and thus pass on the mutation to their children.

A 2021 study, though, shows an additional benefit for athletes with the HFE mutation. Competitive cyclists with HFE mutations have faster performance times and a 17% greater V˙O2 peak.[ref] A little extra iron in the blood leading to additional oxygen capacity?

A 2020 study found that international-level endurance athletes were almost twice as likely to carry the HFE H63D variant. The researchers think this is due to increased oxygen-binding capacity with higher iron.[ref]

The H63D mutation may decrease the risk of neurodegeneration due to the pesticide paraquat.(animal study)[ref]

Hemochromatosis Genotype Report:

Not a member? Join here. Membership lets you see your data right in each article and also gives you access to the member’s only information in the Lifehacks sections.

HFE Gene Mutations:

The most common type of hemochromatosis is Type 1, or Classic, usually caused by variants in the HFE gene.

Check your genetic data for rs1800562 C282Y (23andMe v4, v5; AncestryDNA):

- A/A: two copies of the C282Y variant, most common cause of hereditary hemochromatosis, highest ferritin levels

- A/G: one copy of C282Y, increased ferritin levels, hemochromatosis possible but less likely[ref], check to see if combined with H63D (below) – combo increases the risk of hemochromatosis, increased risk of obesity [ref]

- G/G: typical

Members: Your genotype for rs1800562 is —.

Check your genetic data for rs1799945 H63D (23andMe v4, v5; AncestryDNA):

- G/G: two copies of the H63D variant can cause (usually mild) hemochromatosis, increased ferritin levels

- C/G: one copy of H63D, somewhat higher ferritin levels, can cause hemochromatosis in conjunction with one copy of C282Y (above)

- C/C: typical

Members: Your genotype for rs1799945 is —.

Check your genetic data for rs1800730 S65C (23andMe v4; AncestryDNA):

- T/T: two copies of the S65C variant can cause (usually milder) hemochromatosis, increased ferritin levels

- A/T: possibly increased ferritin levels

- A/A: typical

Members: Your genotype for rs1800730 is —.

Carrying just one copy of the HFE variant (mainly C282Y):

While most official hemochromatosis sites say that you are ‘just a carrier’ for hemochromatosis with one copy of the HFE variant, excess iron could be causing problems (just not usually to the extent of liver failure). The initial issues with too much iron include random joint pain, fatigue, irritability, and/or abdominal pain.

Research studies also show that carriers of HFE variants (mainly C282Y) are at a higher risk of :

- non-alcoholic fatty liver disease[ref][ref]

- metabolic syndrome[ref]

- cardiovascular disease[ref] including women with heterozygous variants[ref]

- slightly higher risk of cancer[ref][ref] including breast cancer[ref] and liver cancer[ref]

- Alzheimer’s disease, including heterozygous carriers[ref]

- musculoskeletal problems (arthritis symptoms)[ref]

- high blood pressure[ref]

- high uric acid (gout[ref]

- lung fibrosis[ref]

- diabetes[ref]

- cardiovascular disease in kidney disease patients[ref]

- increased lead levels[ref][ref]

Other Genes Involved in Iron Buildup:

Not everyone who is homozygous or compound heterozygous for the hemochromatosis variants will develop iron overload. Diet and lifestyle play a role in the rate at which iron accumulates. Additionally, other genes play a role in ferritin levels and iron levels in the body. Some of these are listed below:

HIF1A gene:

Encodes hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha, which is a transcription regulator (turns on and off other genes) in response to low oxygen.

Check your genetic data for rs11549465 Pro582Ser (23andMe v4, v5; AncestryDNA):

- C/C: typical

- C/T: increased HIF-1a; increased likelihood of having high iron in hemochromatosis patients

- T/T: increased HIF-1a; increased likelihood of having high iron in hemochromatosis patients[ref]

Members: Your genotype for rs11549465 is —.

BMP2 gene:

Responsible for bone morphogenetic proteins influencing hepcidin levels, which regulate iron accumulation.

Check your genetic data for rs235756 (23andMe v4; AncestryDNA):

- G/G: lower transferrin

- A/G: increased transferrin

- A/A: most common genotype; increased ferritin levels in people with HFE variants[ref][ref]

Members: Your genotype for rs235756 is —.

BTBD9 gene:

Check your genetic data for rs3923809 (23andMe v4, v5; AncestryDNA):

- G/G: higher ferritin levels[ref]

- A/G: higher ferritin levels

- A/A: lower ferritin levels

Members: Your genotype for rs3923809 is —.

TMPRSS6 gene:

A transmembrane protease gene, Serine 6, which regulates hepcidin levels

Check your genetic data for rs855791 (23andMe v4, v5; AncestryDNA):

- G/G: higher iron stores in men with HFE variants[ref]

- A/G: higher iron stores in men with HFE variants

- A/A: lower iron stores in men

Members: Your genotype for rs855791 is —.

SLC40A1 gene:

Encodes ferroportin, which transfers iron across the cell membrane in the intestines.

Check your genetic data for rs11568350 Q248H (AncestryDNA):

- C/C: typical

- A/C: higher ferritin levels (especially in African American men)[ref]

- A/A: higher ferritin levels (especially in African American men)[ref] children less likely to be anemic[ref]

Members: Your genotype for rs11568350 is —.

If you have whole-genome sequencing data, check for rs1439816 (SLC40A1 gene) – C allele may lead to more liver damage[ref][ref]

Rare genetic mutations causing other forms of hemochromatosis:

Hemochromatosis can also cause mutations in other iron regulatory genes. These are really rare, but the mutations can cause hemochromatosis starting at a young age.

Check your genetic data for rs121434375 (23andMe i5001498 v4; AncestryDNA):

- A/A: typical*

- A/T: HFE2, pathogenic for hemochromatosis type 2A[ref]

- T/T: ignore if sequencing.com whole genome converted file

*Note: given in the forward orientation. This i number may be incorrect in converted whole genome files from sequencing.com

Members: Your genotype for rs121434375 is — or for i5001498 is —.

Check your genetic data for rs28939076 (23andMe v4; AncestryDNA):

- G/G: typical

- G/T: Hemochromatosis type 4[ref]

Members: Your genotype for rs28939076 is —.

Lifehacks:

Blood tests:

Adult men and menopausal women who are heterozygous or homozygous for any of the HFE variants should, in my not-a-doctor opinion, get their serum iron, TIBC, and ferritin levels checked or ask their doctor to test them.

Ordering serum iron w/ TIBC and ferritin should give you enough information to know if you are storing too much iron. If you want to order your own test, an inexpensive option in the US is UltaLabs. If you wish your insurance or country’s health services to cover the test, talk with your doctor and explain that you carry a genetic mutation in the HFE gene.

Give Blood Regularly

If you have slightly elevated iron levels, the simplest way to manage iron levels is to give blood regularly. You will likely feel good, and you will definitely help out someone else with your blood donation. It is a win-win!

Fatty liver disease risk:

People with HFE mutations and hemochromatosis are at an increased risk of fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Talk with your doctor about testing for NAFLD.

Related article: Fatty Liver Disease: Genetic variants that increase the risk of NAFLD

Natural Iron Chelators and Inhibitors:

While giving blood is the most effective way to reduce iron levels, natural and pharmaceutical iron chelators can also help.[ref]

Drinking tea, coffee, or cocoa with a meal decreases iron absorption considerably.[ref]

Quercetin, a flavonoid found in fruits and vegetables, has been studied for its iron-chelating properties.[ref] A 2017 study on dendritic (immune system) cells found that quercetin “increases extracellular iron export, resulting in an overall decrease in the intracellular iron content and consequent diminished inflammatory abilities.”[ref] A 2014 study on quercetin concluded: “Potentially, diets rich in polyphenols might be beneficial for patients groups at risk of iron loading by limiting the rate of intestinal iron absorption.” Foods high in quercetin include apples, dark cherries, tomatoes, capers, onions, and cranberries. Quercetin supplements, including pure quercetin powder, are also readily available.

Related article: Quercetin, absorption, genetic interactions

Another flavonoid, rutin, a quercetin metabolite, has also been studied for its iron chelation properties.[ref] A 2014 study in rats found: “Rutin administration to iron-overloaded rats resulted in a significant decrease in serum total iron, TIBC, Tf, TS%, ferritin levels…”[ref] Foods high in rutin include capers, black olives, buckwheat, asparagus, and berries. Rutin is also available as a supplement.

Melatonin is a natural antioxidant produced by the body in high amounts during the night. It is also essential to preventing oxidative damage in iron overload.[ref][ref] As we age, we produce less melatonin at night. Additionally, exposure to blue light (electronics, bright overhead lights) in the evening hours also reduces melatonin production.

Related article: Supplemental melatonin

Taurine, in a mouse model of hemochromatosis, was found to protect against liver damage from excess iron. The study is worth reading and looking into if you are worried about iron-induced liver damage.

Okra: A 2015 study found that okra “dramatically decreases intracellular iron levels in H63D cells compared to untreated cells”.[ref] Time to make some gumbo.

Dietary phenols such as EGCG from green tea and grape seed extract also have been shown to inhibit iron uptake in the intestinal cells.[ref]

The jury is still out on curcumin. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, cross-over study, curcumin was found to decrease hepcidin and increase ferritin.[ref] Other studies refer to curcumin as a possible iron chelator.[ref]

Avoiding Iron-Fortified Foods…

Research points to iron-fortified foods as a problem for those carrying hemochromatosis genetic variants.[ref] In the US, white rice and refined wheat products are fortified with iron (e.g., bread, cereal, and pasta – all have iron added).

- A Swedish study looked at the effect of iron-fortified foods on iron absorption in men with hemochromatosis.[ref] The study found that eliminating iron fortification from foods significantly reduced the iron absorbed by the men in the study. The study also found that the time needed between phlebotomy (to maintain proper iron levels in hemochromatosis patients) was increased significantly.

- A US study in 2012, though, declared that there is no evidence dietary iron content made a difference in ferritin concentration. In the study, they gave 200 people (homozygous for the HFE C282Y variant and high serum ferritin levels) surveys asking for information on the type of diet they had eaten for the last few years as well as alcohol intake. Then they compared the survey data to their serum ferritin levels to look for a correlation and concluded that iron intake doesn’t impact hemochromatosis.[ref]

Quick tip: Read the labels on packaged foods to see if they are enriched with iron. Often organic foods will not be enriched, or you can get organic flour that doesn’t have iron added to make your bread.

Cut out the alcohol:

With excess iron already stressing out your liver, don’t add to the problem by overconsuming alcohol. The most significant risk factor for liver failure, along with the C282Y mutation, is the addition of alcohol. Heavy drinkers with the mutation have a 9-fold increased risk of cirrhosis.[ref]

Historical perspective: Leeches, Bloodletting, and Iron fortification

While researching all of this, it hit me that the bloodletters of yesteryear probably did help a small minority of people who were overloaded with iron. Using leeches to reduce iron stores was probably effective against some bacterial infections, and reducing iron levels likely helped the immune response to other infections as well…

Iron fortification into all wheat products in the US, which began in the 1940s, is likely good for children and most women of childbearing age. But… it adds significantly to the iron overload burden for some men and older women.

When looking at the mandated fortification of foods with iron and folic acid, policymakers focus on the majority at the expense of those who are genetically harmed by it.

Extras for Members:

Related Articles and Topics:

Lithium Orotate + B12: Boosting mood and decreasing anxiety, for some people…

For some people, low-dose, supplemental lithium orotate is a game-changer for mood issues when combined with vitamin B12. But other people may have little to no response. The difference may be in your genes.

Is inflammation causing your depression or anxiety?

Research over the past two decades clearly shows a causal link between increased inflammatory markers and depression. Genetic variants in the inflammatory-related genes can increase the risk of depression and anxiety.

Alzheimer’s and APOE genotype

One very important gene that has been extremely well-researched for Alzheimer’s disease is the APOE gene. This gene carries cholesterol and other fats in your bloodstream, and a common variant of the gene is linked to a higher risk of Alzheimer’s.

Diabetes: Genetic Risk Report

We often talk about diabetes as though it is one disease, but diabetes can have several different causes or pathways that are impacting glucose regulation. Tailoring your diabetes prevention (or reversal) efforts to fit your genetic susceptibility may be more effective.

References

Baccan, Mayara Marinovic, et al. “Quercetin as a Shuttle for Labile Iron.” Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry, vol. 107, no. 1, Feb. 2012, pp. 34–39. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.11.014.

Badria, Farid A., et al. “Curcumin Attenuates Iron Accumulation and Oxidative Stress in the Liver and Spleen of Chronic Iron-Overloaded Rats.” PloS One, vol. 10, no. 7, 2015, p. e0134156. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0134156.

Ben-Arieh, Sayeh Vahdati, et al. “Human Cytomegalovirus Protein US2 Interferes with the Expression of Human HFE, a Nonclassical Class I Major Histocompatibility Complex Molecule That Regulates Iron Homeostasis.” Journal of Virology, vol. 75, no. 21, Nov. 2001, pp. 10557–62. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.75.21.10557-10562.2001.

Camacho, António, et al. “Effect of C282Y Genotype on Self-Reported Musculoskeletal Complications in Hereditary Hemochromatosis.” PloS One, vol. 10, no. 3, 2015, p. e0122817. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122817.

—. “Effect of C282Y Genotype on Self-Reported Musculoskeletal Complications in Hereditary Hemochromatosis.” PloS One, vol. 10, no. 3, 2015, p. e0122817. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122817.

Castiella, Agustin, et al. “Impact of H63D Mutations, Magnetic Resonance and Metabolic Syndrome among Outpatient Referrals for Elevated Serum Ferritin in the Basque Country.” Annals of Hepatology, vol. 14, no. 3, June 2015, pp. 333–39.

Distante, S., et al. “The Origin and Spread of the HFE-C282Y Haemochromatosis Mutation.” Human Genetics, vol. 115, no. 4, Sept. 2004, pp. 269–79. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-004-1152-4.

Drakesmith, Hal, et al. “HIV-1 Nef down-Regulates the Hemochromatosis Protein HFE, Manipulating Cellular Iron Homeostasis.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 102, no. 31, Aug. 2005, pp. 11017–22. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0504823102.

Ellervik, Christina, et al. “Total Mortality by Elevated Transferrin Saturation in Patients With Diabetes.” Diabetes Care, vol. 36, no. 9, Sept. 2013, pp. 2646–54. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-2032.

—. “Total Mortality by Elevated Transferrin Saturation in Patients With Diabetes.” Diabetes Care, vol. 36, no. 9, Sept. 2013, pp. 2646–54. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-2032.

Flais, Jérémy, et al. “Hyperferritinemia Increases the Risk of Hyperuricemia in HFE-Hereditary Hemochromatosis.” Joint Bone Spine, vol. 84, no. 3, May 2017, pp. 293–97. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2016.05.020.

Galleggiante, Vanessa, et al. “Dendritic Cells Modulate Iron Homeostasis and Inflammatory Abilities Following Quercetin Exposure.” Current Pharmaceutical Design, vol. 23, no. 14, 2017, pp. 2139–46. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612823666170112125355.

Gordeuk, Victor R., et al. “Dietary Iron Intake and Serum Ferritin Concentration in 213 Patients Homozygous for the HFEC282Y Hemochromatosis Mutation.” Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology, vol. 26, no. 6, June 2012, pp. 345–49.

Grosse, Scott D., et al. “Clinical Penetrance in Hereditary Hemochromatosis: Estimates of the Cumulative Incidence of Severe Liver Disease among HFE C282Y Homozygotes.” Genetics in Medicine, vol. 20, no. 4, Apr. 2018, pp. 383–89. www.nature.com, https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2017.121.

Guo, Maolin, et al. “Iron-Binding Properties of Plant Phenolics and Cranberry’s Bio-Effects.” Dalton Transactions (Cambridge, England : 2003), no. 43, Nov. 2007, pp. 4951–61. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1039/b705136k.

Hemochromatosis | Iron Disorders Institute. https://irondisorders.org/hemochromatosis/. Accessed 2 Sept. 2021.

Hollerer, Ina, et al. “Pathophysiological Consequences and Benefits of HFE Mutations: 20 Years of Research.” Haematologica, vol. 102, no. 5, May 2017, pp. 809–17. haematologica.org, https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2016.160432.

Hurrell, R. F., et al. “Inhibition of Non-Haem Iron Absorption in Man by Polyphenolic-Containing Beverages.” The British Journal of Nutrition, vol. 81, no. 4, Apr. 1999, pp. 289–95.

Kayaalti, Zeliha, et al. “Maternal Hemochromatosis Gene H63D Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism and Lead Levels of Placental Tissue, Maternal and Umbilical Cord Blood.” Environmental Research, vol. 140, July 2015, pp. 456–61. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2015.05.004.

Kemna, Erwin H. J. M., et al. “Hepcidin: From Discovery to Differential Diagnosis.” Haematologica, vol. 93, no. 1, Jan. 2008, pp. 90–97. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.11705.

Lainé, Fabrice, et al. “Curcuma Decreases Serum Hepcidin Levels in Healthy Volunteers: A Placebo-Controlled, Randomized, Double-Blind, Cross-over Study.” Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology, vol. 31, no. 5, Oct. 2017, pp. 567–73. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/fcp.12288.

Liu, Juan, et al. “HFE Inhibits Type I IFNs Signaling by Targeting the SQSTM1-Mediated MAVS Autophagic Degradation.” Autophagy, vol. 17, no. 8, pp. 1962–77. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2020.1804683.

Lopez, Christopher A., and Eric P. Skaar. “The Impact of Dietary Transition Metals on Host-Bacterial Interactions.” Cell Host & Microbe, vol. 23, no. 6, June 2018, pp. 737–48. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.008.

Ma, Qianyi, et al. “Bioactive Dietary Polyphenols Decrease Heme Iron Absorption by Decreasing Basolateral Iron Release in Human Intestinal Caco-2 Cells.” The Journal of Nutrition, vol. 140, no. 6, June 2010, pp. 1117–21. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.109.117499.

Milet, Jacqueline, et al. “Common Variants in the BMP2, BMP4, and HJV Genes of the Hepcidin Regulation Pathway Modulate HFE Hemochromatosis Penetrance.” American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 81, no. 4, Oct. 2007, pp. 799–807.

Milman, Nils Thorm, et al. “Diagnosis and Treatment of Genetic HFE-Hemochromatosis: The Danish Aspect.” Gastroenterology Research, vol. 12, no. 5, Oct. 2019, pp. 221–32. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.14740/gr1206.

—. “Diagnosis and Treatment of Genetic HFE-Hemochromatosis: The Danish Aspect.” Gastroenterology Research, vol. 12, no. 5, Oct. 2019, pp. 221–32. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.14740/gr1206.

—. “Diagnosis and Treatment of Genetic HFE-Hemochromatosis: The Danish Aspect.” Gastroenterology Research, vol. 12, no. 5, Oct. 2019, pp. 221–32. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.14740/gr1206.

Mohammad, Ausaf, et al. “High Prevalence of Fibromyalgia in Patients with HFE-Related Hereditary Hemochromatosis.” Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, vol. 47, no. 6, July 2013, pp. 559–64. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0b013e31826f7ad7.

Olsson, K. S., et al. “The Effect of Withdrawal of Food Iron Fortification in Sweden as Studied with Phlebotomy in Subjects with Genetic Hemochromatosis.” European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 51, no. 11, Nov. 1997, pp. 782–86. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600488.

Page, Malcom G. P. “The Role of Iron and Siderophores in Infection, and the Development of Siderophore Antibiotics.” Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, vol. 69, no. Suppl 7, Dec. 2019, pp. S529–37. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciz825.

Rametta, Raffaela, et al. “From Environment to Genome and Back: A Lesson from HFE Mutations.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 21, no. 10, May 2020, p. 3505. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21103505.

—. “From Environment to Genome and Back: A Lesson from HFE Mutations.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 21, no. 10, May 2020, p. 3505. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21103505.

Reuben, Alexandre, et al. “The Hemochromatosis Protein HFE 20 Years Later: An Emerging Role in Antigen Presentation and in the Immune System.” Immunity, Inflammation and Disease, vol. 5, no. 3, Apr. 2017, pp. 218–32. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1002/iid3.158.

—. “The Hemochromatosis Protein HFE 20 Years Later: An Emerging Role in Antigen Presentation and in the Immune System.” Immunity, Inflammation and Disease, vol. 5, no. 3, Apr. 2017, pp. 218–32. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1002/iid3.158.

Roest, M., et al. “Heterozygosity for a Hereditary Hemochromatosis Gene Is Associated with Cardiovascular Death in Women.” Circulation, vol. 100, no. 12, Sept. 1999, pp. 1268–73. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.100.12.1268.

Sangiuolo, Federica, et al. “HFE Gene Variants and Iron-Induced Oxygen Radical Generation in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis.” The European Respiratory Journal, vol. 45, no. 2, Feb. 2015, pp. 483–90. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00104814.

Semenova, Ekaterina A., et al. “The Association of HFE Gene H63D Polymorphism with Endurance Athlete Status and Aerobic Capacity: Novel Findings and a Meta-Analysis.” European Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 120, no. 3, 2020, pp. 665–73. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-020-04306-8.

Shen, L. L., et al. “Implicating the H63D Polymorphism in the HFE Gene in Increased Incidence of Solid Cancers: A Meta-Analysis.” Genetics and Molecular Research: GMR, vol. 14, no. 4, Oct. 2015, pp. 13735–45. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.4238/2015.October.28.36.

Song, Insung Y., et al. “The Nrf2-Mediated Defense Mechanism Associated with HFE Genotype Limits Vulnerability to Oxidative Stress-Induced Toxicity.” Toxicology, vol. 441, Aug. 2020, p. 152525. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2020.152525.

Thakkar, Drishti, et al. “HFE Genotype and Endurance Performance in Competitive Male Athletes.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, vol. 53, no. 7, July 2021, pp. 1385–90. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000002595.

Ye, Qing, et al. “Association between the HFE C282Y, H63D Polymorphisms and the Risks of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Liver Cirrhosis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 5,758 Cases and 14,741 Controls.” PloS One, vol. 11, no. 9, 2016, p. e0163423. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163423.

Zhang, Meng, et al. “Meta-Analysis of the Association between H63D and C282Y Polymorphisms in HFE and Cancer Risk.” Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention: APJCP, vol. 16, no. 11, 2015, pp. 4633–39. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.11.4633.

ZHANG, ZEYU, et al. “Taurine Supplementation Reduces Oxidative Stress and Protects the Liver in an Iron-Overload Murine Model.” Molecular Medicine Reports, vol. 10, no. 5, Nov. 2014, pp. 2255–62. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2014.2544.