Key takeaways:

~Alpha-1 adrenergic receptors play a pivotal role in regulating blood pressure and heart rate by mediating blood vessel constriction and responding to stress-induced catecholamine release.

~ The diving reflex, triggered by cold water contact, is an example of how the alpha-1 adrenergic receptor helps to prioritize oxygen delivery to essential organs through blood vessel constriction and heart rate reduction.

~ Genetic variants in the ADRA1A gene increase the risk of the stress response, fainting, and the diving reflex, with some variants linked to conditions like POTS, vasovagal syncope, and even cognitive impairments.

~ Lifestyle and dietary choices, such as consuming blueberries or maintaining adequate calcium levels, may modulate alpha-1 adrenergic receptor activity and improve cardiovascular health.

Alpha-1 Adrenergic receptor: heart rate and vascular constriction

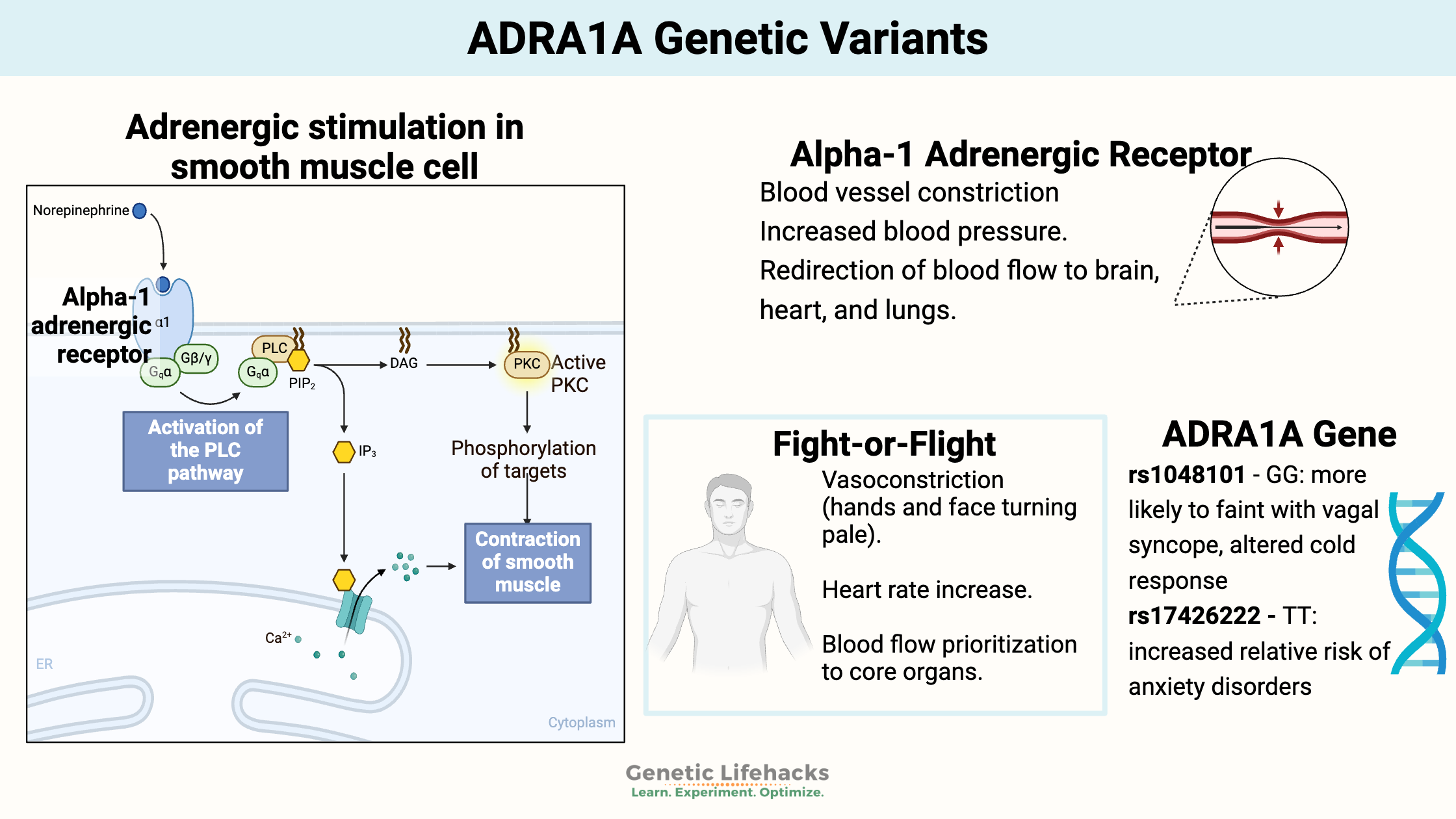

Adrenergic receptors are a class of receptors that bind with catecholamines, such as epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline). When a catecholamine binds to these receptors, it generally stimulates the sympathetic nervous system (fight-or-flight).[ref]

There are several types of adrenergic receptors, most of which act to either activate or relax muscles.

The α1-adrenergic receptors (ADRA1A) are essential in how the muscles surrounding your blood vessels contract to change blood pressure and flow. These muscles are called the vascular smooth muscles.

ADRA1A receptors are also important in the control of heart rate, as well as the gastrointestinal and urinary system sphincters.[ref]

We have many systems in place to control blood pressure and heart rate. The α1-adrenergic receptors react to epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline) to control blood vessel reactivity when stressed.

But that is only part of the story with α1-adrenergic receptors. Researchers recently discovered they are also important in cognitive function and neurotransmission.[ref]

Blood pressure:

Alpha-1 adrenergic receptor activation causes blood vessels to constrict. For example, if you are stressed out and produce a bunch of adrenaline (epinephrine), the blood vessels in your extremities will constrict, and your blood pressure will rise. The vasoconstriction in your extremities is why your hands and even your face may look pale when you have had a shock or stress. All the blood is being prioritized to go to the heart, brain, and lungs.

You may be somewhat familiar with the alpha-1 adrenergic receptor when it comes to blood pressure medications. Commonly called alpha-blockers, blood pressure medications, such as doxazosin, that target the alpha-1 adrenergic receptors have been available for decades. Just like the name implies, alpha blocker are going to block the alpha-1 adrenergic receptor, preventing blood pressure from rising due to catecholamine release.

There is more to this adrenergic receptor story, though, than just blood pressure medicine.

Diving Reflex and Oxygen:

We have an innate reflex that kicks in when going underwater. Called the ‘diving reflex’, this automatic reflex causes babies to hold their breath underwater — and to a lesser extent, applies to the changes in adults as well.

Essentially, the diving reflex is a way mammals save oxygen when underwater through constriction of peripheral blood vessels, redistribution of blood flow to vulnerable organisms, a decrease in heart rate (bradycardia), release of red blood cells from the spleen, and usually an increase in blood pressure. This same reflex happens whether completely submerged in water or just dunking your face into a bowl of cold water. Water going up the nose triggers the trigeminal nerve and the diving reflex.

The constriction of blood vessels in the diving reflex is due to catecholamines binding to the ADRA1A receptor.

A recent study in adults who were not trained in diving looked at how ADRA1A genetic variants affect the diving reflex. The study found that participants with the variant had less vasodilation and, therefore, less blood flow to the lungs when diving.[ref]

Syncope (Fainting)

Fainting (also called syncope) can be caused by a lack of blood flow to the brain.

Vasovagal syncope is fainting caused by abnormal autonomic control of blood circulation. Essentially, the normal regulation of blood circulation is out of wack. The parasympathetic nervous system is overactivated and causes low arterial blood pressure and low blood flow to the brain.[ref]

What triggers vasovagal syncope (fainting)?

Orthostatic stress (standing up), emotional stress, medical manipulations — all can cause autonomic reactions such as flushing and nausea, followed by passing out.[ref]

Genetic variants in the ADRA1A gene (listed below) are linked to an increased risk of vasovagal syncope. Fainting was also a side effect of the initial alpha-blocker medications that became available in the 1970s.[ref]

Long Covid, Spike Protein, and Adrenergic Receptors:

Recently, researchers found that patients with long Covid are more likely to have autoantibodies targeting adrenoceptors – specifically β2- and α1-adrenoceptors.[ref]

Antibodies targeting the α1-adrenoceptors could explain some of the issues with heart rate, POTS, and cognition in people with long Covid or post-vaccination.

POTS (postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome) is also linked in studies to autoantibodies targeting the alpha-1 adrenergic receptor. A 2019 study found that 89% of POTS patients had autoantibodies to the alpha-1 adrenergic receptors and that most of the patients had developed POTS following a viral infection.[ref]

Pain syndromes and peripheral nerve injury:

In some patients with complex regional pain syndrome, alpha-1 adrenergic receptors are overexpressed, compared to a normal control group. The activation of the alpha-1 adrenergic receptors in the epidermal (skin) cells causes an increase in IL-6, an inflammatory mediator. [ref]

When a nerve is injured, mast cells, white blood cells, and fibroblasts move to the site of injury to start the repair process. Research also shows that alpha-1 adrenoceptors are increased in areas of peripheral nerve injuries.[ref]

Neurological Conditions

Alpha-1 adrenergic antibodies are found at higher levels in people with Alzheimer’s than in people without Alzheimer’s. One study found that 59% of Alzheimer’s dementia patients had alpha-1 and beta-2 adrenergic receptor antibodies, compared to only 17% in an age-matched control group with neurological impairments other than Alzheimer’s or vascular dementia. The study’s authors link the adrenergic receptor antibodies to changes in blood flow to the brain.[ref]

Another study explains why autoantibodies to alpha-1 adrenergic receptors could cause dementia. The researchers explain that the autoantibodies bind to the receptor and cause a chronic activation that raises intracellular calcium levels. “An animal model has shown that agAAB [alpha-1 adrenoceptor agonistic antibodies] causes macrovascular and microvascular impairment in the vessels of the brain. Reduction in blood flow and the density of intact vessels was significantly demonstrated.”[ref]

Colon contractions

The ADRA1A receptors are also found in the muscles surrounding the colon. Norepinephrine release inhibits colonic contractions when binding to ADRA1A.[ref] This is one way that stress affects your gastrointestinal health on an acute basis.

ADRA1A Genotype Report

Lifehacks:

Medications that affect ADRA1A:

Alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonists (blockers) include:[ref]

- Olanzapine

- Doxazocin

- Risperidone

- Prazosin

- Trazodone

Alpha-1 adrenergic receptor agonists (activators) include:

- Synephrine

- Pseudoephedrine (decongestant)

- Oxymetazoline (Afrin)

- Tetryzoline (eye drops)

Blueberries:

Related Articles and Topics:

Small Fiber Neuropathy: Genetics, Causes, and Possible Solutions

References:

Baranova, Tatyana, et al. “Vascular Reactions of the Diving Reflex in Men and Women Carrying Different ADRA1A Genotypes.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 23, no. 16, Aug. 2022, p. 9433. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23169433.

Carruthers, S. G. “Adverse Effects of Alpha 1-Adrenergic Blocking Drugs.” Drug Safety, vol. 11, no. 1, July 1994, pp. 12–20. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-199411010-00003.

Curtis, Peter J., et al. “Blueberries Improve Biomarkers of Cardiometabolic Function in Participants with Metabolic Syndrome—Results from a 6-Month, Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 109, no. 6, June 2019, pp. 1535–45. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy380.

Deji, Cuola, et al. “Association Study of Catechol-o-Methyltransferase and Alpha-1-Adrenergic Receptor Gene Polymorphisms with Multiple Phenotypes of Heroin Use Disorder.” Neuroscience Letters, vol. 748, Mar. 2021, p. 135677. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2021.135677.

Freitas, Silvia R., et al. “Association of Alpha1a-Adrenergic Receptor Polymorphism and Blood Pressure Phenotypes in the Brazilian Population.” BMC Cardiovascular Disorders, vol. 8, Dec. 2008, p. 40. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-8-40.

Hatton, D. C., et al. “Dietary Calcium Modulates Blood Pressure through Alpha 1-Adrenergic Receptors.” American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology, vol. 264, no. 2, Feb. 1993, pp. F234–38. journals.physiology.org (Atypon), https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.2.F234.

Hernández-Pacheco, Guadalupe, et al. “Arg347Cys Polymorphism of Α1a-Adrenergic Receptor in Vasovagal Syncope. Case-Control Study in a Mexican Population.” Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic & Clinical, vol. 183, July 2014, pp. 66–71. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2014.01.005.

Jolma, Pasi, et al. “High-Calcium Diet Enhances Vasorelaxation in Nitric Oxide-Deficient Hypertension.” American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology, vol. 279, no. 3, Sept. 2000, pp. H1036–43. journals.physiology.org (Atypon), https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.3.H1036.

Kelsey, Robert M., et al. “ALPHA-ADRENERGIC RECEPTOR GENE POLYMORPHISMS AND CARDIOVASCULAR REACTIVITY TO STRESS IN BLACK ADOLESCENTS AND YOUNG ADULTS.” Psychophysiology, vol. 49, no. 3, Mar. 2012, pp. 401–12. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01319.x.

Kurahashi, Masaaki, et al. “Norepinephrine Has Dual Effects on Human Colonic Contractions Through Distinct Subtypes of Alpha 1 Adrenoceptors.” Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology, vol. 10, no. 3, 2020, pp. 658-671.e1. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.04.015.

Levran, Orna, et al. “Heroin Addiction in African Americans: A Hypothesis-Driven Association Study.” Genes, Brain, and Behavior, vol. 8, no. 5, July 2009, pp. 531–40. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00501.x.

Matsunaga, Tetsuro, et al. “Alpha-Adrenoceptor Gene Variants and Autonomic Nervous System Function in a Young Healthy Japanese Population.” Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 52, no. 1, 2007, p. 28. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10038-006-0076-3.

MATUŠKOVÁ, Lenka, and Michal JAVORKA. “Adrenergic Receptors Gene Polymorphisms and Autonomic Nervous Control of Heart and Vascular Tone.” Physiological Research, vol. 70, no. Suppl 4, Dec. 2021, pp. S495–510. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.33549/physiolres.934799.

Matveeva, Natalia, et al. “Towards Understanding the Genetic Nature of Vasovagal Syncope.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 22, no. 19, Sept. 2021, p. 10316. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms221910316.

Norton, Cynthia, et al. “Wild Blueberry-Rich Diets Affect the Contractile Machinery of the Vascular Smooth Muscle in the Sprague-Dawley Rat.” Journal of Medicinal Food, vol. 8, no. 1, 2005, pp. 8–13. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2005.8.8.

Perez, Dianne M. “Α1-Adrenergic Receptors in Neurotransmission, Synaptic Plasticity, and Cognition.” Frontiers in Pharmacology, vol. 11, 2020. Frontiers, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2020.581098.

Pillay, Yashodani, et al. “Patulin Suppresses Α1-Adrenergic Receptor Expression in HEK293 Cells.” Scientific Reports, vol. 10, no. 1, Nov. 2020, p. 20115. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77157-0.

Puel, Olivier, et al. “Biosynthesis and Toxicological Effects of Patulin.” Toxins, vol. 2, no. 4, Apr. 2010, pp. 613–31. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins2040613.

Shorter, Daryl, et al. “The α-1 Adrenoceptor (ADRA1A) Genotype Moderates the Magnitude of Acute Cocaine-Induced Subjective Effects in Cocaine-Dependent Individuals.” Pharmacogenetics and Genomics, vol. 26, no. 9, Sept. 2016, pp. 428–35. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1097/FPC.0000000000000234.

Wallukat, Gerd, et al. “Functional Autoantibodies against G-Protein Coupled Receptors in Patients with Persistent Long-COVID-19 Symptoms.” Journal of Translational Autoimmunity, vol. 4, Jan. 2021, p. 100100. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtauto.2021.100100.

Zhang, Xiaobin, et al. “Preliminary Evidence for a Role of the Adrenergic Nervous System in Generalized Anxiety Disorder.” Scientific Reports, vol. 7, Feb. 2017, p. 42676. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42676.