Key takeaways:

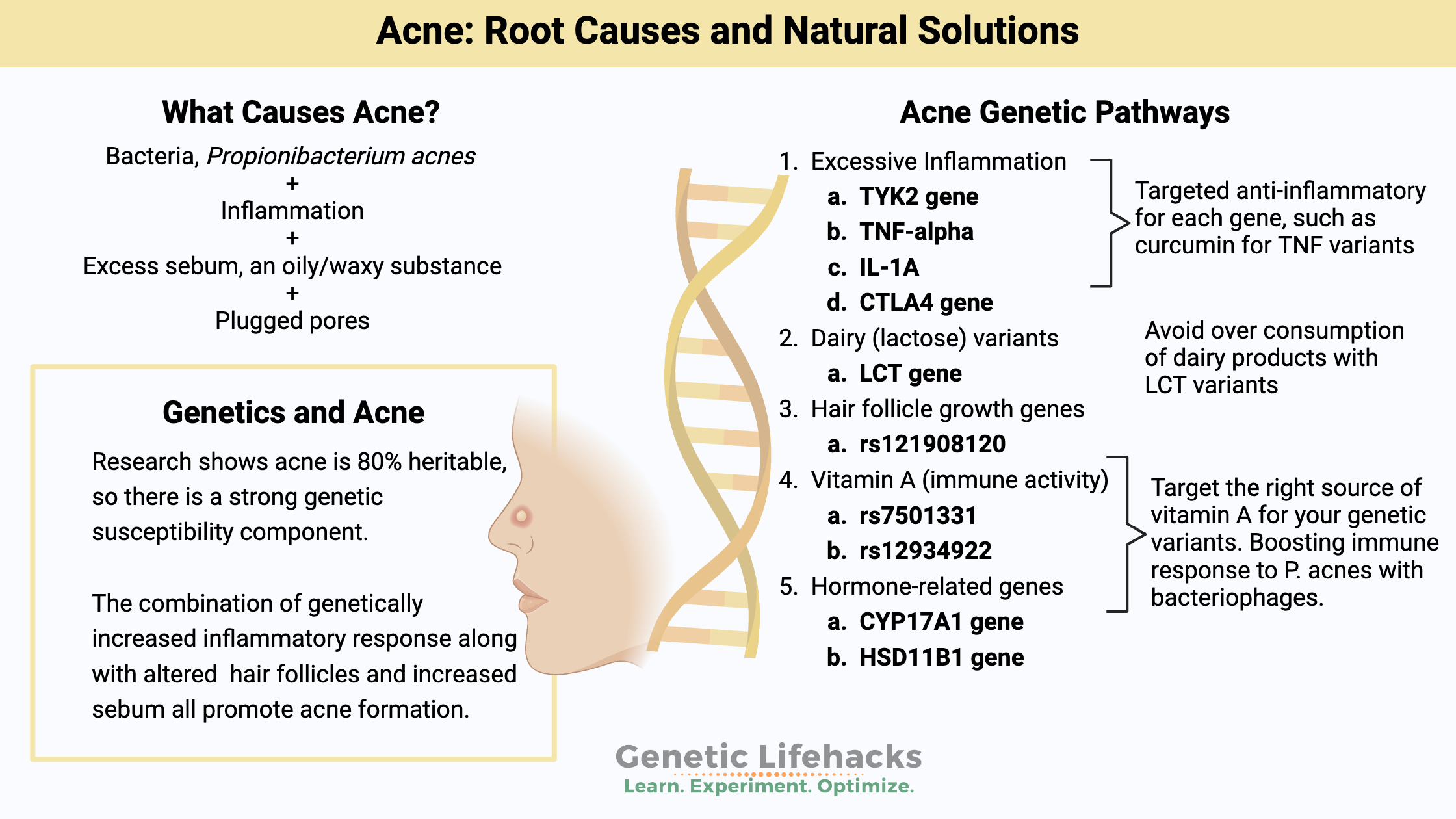

~ Acne has four components: bacteria, plugged pores, excess sebum, and an inflammatory reaction.

~ Diet and lifestyle factors influence breakouts.

~ Genetic variants are really important in who gets acne – and why.

~ Understanding your genetic susceptibility can help you target the right underlying cause of your acne.

Members will see their genotype report below, plus additional solutions in the Lifehacks section. Consider joining today.

Why does acne run in the family?

Ever wonder why some teens and adults can do everything ‘right’ – eat great, wash their faces, etc. – and still have acne? While others can eat pizza three times a day, shower once a week — and end up with perfectly clear skin! Yep, you guessed it. Genetics

A 2013 study puts the cost of acne treatment in the US alone at over $3 billion a year.[ref] That’s a lot of acne cream.

About 80-95% of teens deal with acne, and moderate to severe acne affects 20% of teens. Over 40% of adults in their 20s are still struggling with it.[ref]

Researchers estimate that acne is about 80% heritable, so there is a very strong genetic link to susceptibility to acne.[ref]

There is no single gene that causes acne. Rather, multiple genetic variants (small changes in a gene) increase the risk of acne when combined with the right environmental factors.

There have been quite a few studies digging into the genetic variants that may increase susceptibility to acne. These genetic studies tell us a lot about the root causes of acne and point toward several solutions.

Genetics research (details in the genetics section below) shows that four genetic factors can be involved:

- inflammatory genes

- dairy (lactose) genetic variants

- hair follicle growth genes

- vitamin A conversion

Lifestyle factors combine with genetic susceptibility. And targeting the right root cause may get you on the path to naturally clear skin.

What are the causes of acne?

There are four factors that you need for acne: inflammation, excess sebum, bacteria, and plugged pores.

| Cause | What is it? | Genetic Influence? |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Overgrowth of P. acnes on skin | Immune response genes |

| Plugged Pores | Blockage of hair follicles by excess keratin | Follicle growth genes |

| Excess Sebum | Overactive sebaceous glands (often hormonal) | Androgen metabolism genes |

| Inflammation | Heightened inflammatory response | Cytokine and inflammation genes |

All four of these come together in acne.

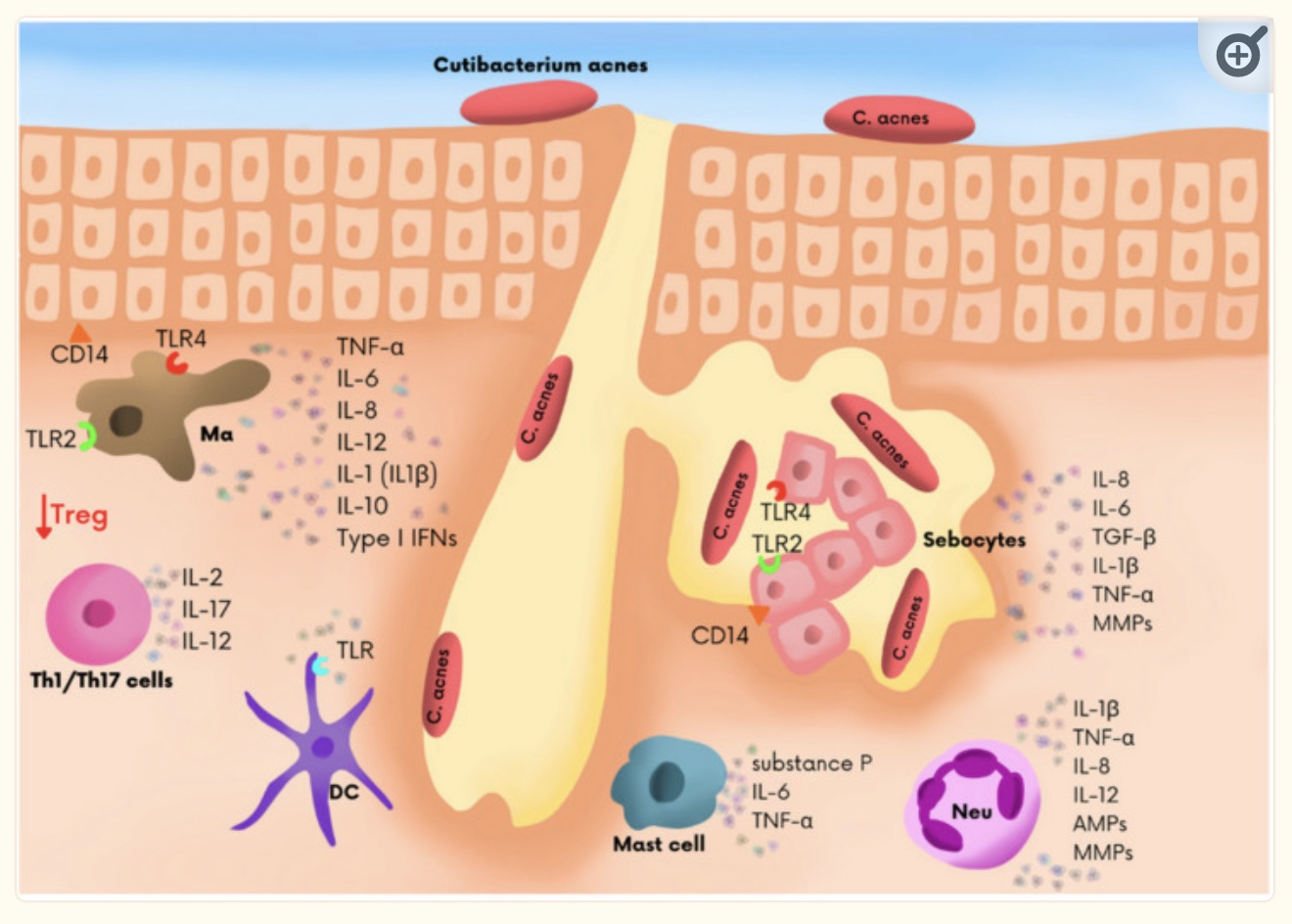

Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes) is a common bacterium found on most people’s skin. (P. acnes is now referred to as Cutibacterium acnes, or C. acnes, in newer studies.) The overcolonization of P. acnes most often occurs on the skin of the nose, face, chest, and back, which are common areas for acne.[ref]

In skin follicles, the P. acnes (C. acnes) bacteria interact with inflammatory cytokines, sebum, and excess keratin to cause acne.

For male teenagers, increased androgen hormones lead to excess sebum production. As testosterone levels increase in teens, excess sebum can lead to acne when combined with inflammation, bacteria, and plugged pores. In particular, DHT (dihydrotestosterone) can increase sebum production.[ref]

Excess sebum, narrowed sebaceous ducts, and hyperkeratosis can cause a blocked hair follicle. This then leads to an inflammatory reaction with increased inflammatory markers in the hair follicles.[ref]

P. acnes (C. acnes) can produce lipase enzymes that convert sebum into other free fatty acids, stimulating the hair follicles.[ref]

The use of antibiotics to eliminate P. acnes has given rise to strains that are now resistant to common antibiotics.[ref]

Can diet affect acne?

Surprisingly, to me, the research studies on poor diet causing acne are not all that clear-cut. Many studies on diet and acne are inconclusive or downright contradictory.[ref]

Research does show a couple of dietary connections that interact with genetic susceptibility:

| Dietary Factor | Genetic Interaction? | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Dairy | Yes (lactase persistence) | The effect varies by population, genetics |

| High glycemic foods | Possible (insulin response genes) | Insulin resistance may be key |

| Vitamin A | Yes (BCMO1 variant) | Retinol form more effective for some |

| Vitamin B12 | Not established | Excess may worsen acne |

1) Dairy and Acne:

According to a meta-analysis, dairy intake increases the risk of acne by about 25-40%, depending on the frequency of dairy consumption.[ref] So why would dairy matter? One theory is that it upregulates mTOR and IGF-1 due to its amino acid composition.[ref]

But… not all studies on dairy and acne agree. It may be due to population differences and whether adolescents/adults are likely to still produce lactase (the enzyme that breaks down lactose in milk).

A Danish study (with 93% of participants producing lactase as adults) found that dairy consumption decreased acne only in people who still produced lactase.[ref] (See the genotype report below to know if you still produce lactase as an adult.)

In general, people of Asian descent are much less likely to produce lactase as adults. So the meta-analysis results on dairy may be more accurate in populations that tend not to produce lactase. The majority (over 90% usually) of people of Northern European heritage still produce lactase. Other population groups vary between those two extremes.

Related article: Lactose Intolerance Genes

2) Sugar and acne

Instead of being able to point the finger at sugar directly, it seems insulin resistance may be a problem with acne.

In a study comparing teens with acne and those without, their fasting blood glucose levels were actually very similar. Interestingly, insulin levels were higher in the teens with acne than in those without.[ref] Another recent study in Singapore also found that diets with a high glycemic index score upregulated genes that are linked to acne.[ref]

Thus, a diet with a high glycemic load (whether high in sugar or other highly processed foods) may play a role in acne. An individual’s response to sugar and starch may be important — e.g., two people can eat the same diet and have a different glycemic response. The study in Singapore also found that eating a lot of fruit reduced the severity and scarring from acne by almost 50%.[ref] While fruits may raise blood sugar in some people, the polyphenols and flavonoids may balance out the glycemic hit.

3) Vitamin A and Acne:

Not getting enough vitamin A in your diet could also increase the risk of acne. A new study shows that vitamin A is essential in the skin’s defense against pathogens, such as P. acnes.[ref] Vitamin A derivatives, known as retinols, are often used topically for acne.[ref]

There are two forms of vitamin A in foods: beta-carotene from plants and the retinol form found in animal foods. Genetic variants impact how well you convert beta-carotene into the active form of vitamin A. (See your vitamin A genes in the genotype report below.)

Related Article: BCO1 Gene: Converting Beta-Carotene to Vitamin A

4. Excess vitamin B12:

The skin microbiota plays a role in acne, and P. acnes overgrowth is a contributing factor for many people. P. acnes (C. acnes) can utilize host B12 for growth and to produce porphyrins that irritate the skin. Supplemental vitamin B12 is linked to an increased risk of acne.[ref][ref]

Bringing together the dietary components: mTOR and gene expression

Cells can sense when nutrients are abundant and increase or decrease gene expression in response.

Genes in the cell nucleus are transcribed into proteins, but not all genes are going to be transcribed and needed in all cells. So there are a bunch of ways that cells can regulate which proteins are synthesized by turning on and off gene transcription and by regulating proteins after transcription (post-transcriptional modification).

Professor Bodo Melnik has theorized about and written several papers on why a Western diet (milk, sugar, saturated fat) causes acne.[ref] Insulin, IGF-1, branched-chain amino acids (such as in dairy proteins), glutamine, and palmitic acid all are nutrients that activate mTORC1, which is a regulator that increases growth in response to abundant nutrients. The negative side of regulation is FOXO1, which tamps down the transcription of the genes related to sebum production and androgen hormones. Dr. Melnik’s theory is that the modern diet is full of sugar (increases insulin), dairy and other sources of branched-chain amino acids, and palmitic acid (saturated fat) — all of which can increase the mTOR pathway and decrease FOXO1.[ref] Plus, research studies show that insulin resistance and increased mTORC1 are associated with acne.[ref]

A new study on metabolic syndrome and acne looked at the gene expression of FOXO1 and mTOR and found no statistical connection between metabolic syndrome and acne. However, they did find that nuclear FOXO1 levels were very low in acne patients compared to a control group. [ref] Another study found that acne patients had higher serum IGF-1 levels on average and that mTOR was upregulated.[ref]

Does inflammation cause acne? Or vice-versa?

One component of acne is increased inflammatory cytokines. The question is whether acne causes the inflammation or whether upregulated inflammatory cytokines are the cause of acne.

A recent study used biopsies of acne skin to see which genes were upregulated or turned on more than normal. Most of the upregulated genes were in the inflammatory pathways.[ref]

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is associated with an increase in acne. A recent Mendelian randomization study found that the genes that are linked to an increased risk of acne are also linked to an increased risk of IBD.[ref]

Genetic variants impact how likely you are to produce higher levels of inflammatory cytokines. This may be the answer to the question of why P. acnes doesn’t cause acne breakouts in everyone — some people are prone to increased inflammation.

Genes that increase inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha, IL-6, IL-1B, and TGF-beta are all linked to an increased risk of acne.[ref][ref] Without the heightened inflammatory response, the P. acnes bacteria may not produce acne.

Acne Genotype Report

Lifehacks: Natural solutions and supplement stacks for acne

Let’s start with some of the research on acne treatments, and then I’ll get into the research on different supplements that may be effective based on your genes. Talk with your doctor or pharmacist if you have questions on supplements, especially if you are on prescription medications.

| Solution | Mechanism | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A (retinol) | Supports skin immunity | Avoid excess, check genotype |

| Red/Blue light therapy | Reduces bacteria/inflammation | Non-pharmacological |

| Bacteriophage creams | Targets P. acnes bacteria | Available in some products |

| Stop B12 supplements | Reduces P. acnes fuel | Especially if supplementing |

| Paleo/low-glycemic diet | Reduces mTOR/insulin spikes | May help some individuals |

Vitamin A for reducing acne:

If you carry the BCMO1 variants and don’t eat beef liver or pasture-raised dairy, you may want to look into a retinol-based vitamin A supplement, such as a retinyl palmitate or cod liver oil.

Vitamin A is a fat-soluble vitamin, so taking high doses of vitamin A for long periods could lead to toxicity. High doses of vitamin A should not be taken if pregnant or trying to get pregnant. If you have questions on how much vitamin A, talk with a doctor or get a blood test done to determine your current vitamin A status. (UltaLabs has a serum vitamin A test for $63, and you can usually get a 20% off coupon for your first order.)

Treating acne with light therapy:

Light at different wavelengths seems to be effective for reducing bacteria and for reducing the inflammatory response.

Red light therapy has been shown to reduce IL-1a in acne in a lab setting.[ref] If you have IL1A variants (above), this may be something to look into.

Light therapy in the blue wavelengths (449 nm, 50 uW/cm2 ) kills the bacteria that causes acne – in a lab setting.[ref]

The majority of studies on light therapy (red-blue wavelengths) show a benefit for acne.[ref] I don’t know if light therapy is a total cure for everyone, but it is a non-pharmacological approach worth checking out.

Fight fire with fire – using bacteria to treat acne:

Bacteriophages, viruses that kill bacteria, are one exciting possibility for treating acne. There are identified phages that kill P. acnes. Other bacteria can also weed out an overgrowth of P. acnes.[ref][ref]

Creams are available with bacteriophages that target acne bacteria.

Does intermittent fasting or a Paleo diet help with acne?

Here is an interesting paper on how our modern diet (refined carbs, trans fats, etc.) is upregulating mTOR and downregulating FOXO1. The conclusion is that a Paleo-style diet or periodic calorie restriction may help with acne.

Stop supplementing with vitamin B12:

If you take B12 as a stand-alone supplement or as part of a B-complex, consider stopping the supplement for a while to see if it improves your acne. [ref]

7 Natural supplements that reduce inflammation in acne:

Related Articles and Topics:

Specialized Pro-resolving Mediators (SPMs): The Resolution of Inflammation

References:

Bhate, K., and H. C. Williams. “Epidemiology of Acne Vulgaris.” The British Journal of Dermatology, vol. 168, no. 3, Mar. 2013, pp. 474–85. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.12149.

Boyd, Jeffrey M., et al. “Propionibacterium Acnes Susceptibility to Low-Level 449 Nm Blue Light Photobiomodulation.” Lasers in Surgery and Medicine, vol. 51, no. 8, Oct. 2019, pp. 727–34. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/lsm.23087.

Castillo, David E., et al. “Propionibacterium (Cutibacterium) Acnes Bacteriophage Therapy in Acne: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives.” Dermatology and Therapy, vol. 9, no. 1, Dec. 2018, pp. 19–31. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-018-0275-9.

Chamaie-Nejad, F., et al. “Association of the CYP17 MSP AI (T-34C) and CYP19 Codon 39 (Trp/Arg) Polymorphisms with Susceptibility to Acne Vulgaris.” Clinical and Experimental Dermatology, vol. 43, no. 2, Mar. 2018, pp. 183–86. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/ced.13321.

Chen, Biao, et al. “Analysis of Potential Genes and Pathways Involved in the Pathogenesis of Acne by Bioinformatics.” BioMed Research International, vol. 2019, June 2019, p. 3739086. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/3739086.

CLATICI, Victor Gabriel, et al. “Diseases of Civilization – Cancer, Diabetes, Obesity and Acne – the Implication of Milk, IGF-1 and MTORC1.” Mædica, vol. 13, no. 4, Dec. 2018, pp. 273–81. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.26574/maedica.2018.13.4.273.

Ehm, Margaret G., et al. “Phenome-Wide Association Study Using Research Participants’ Self-Reported Data Provides Insight into the Th17 and IL-17 Pathway.” PLoS ONE, vol. 12, no. 11, Nov. 2017, p. e0186405. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186405.

Emiroğlu, Nazan, et al. “Insulin Resistance in Severe Acne Vulgaris.” Advances in Dermatology and Allergology/Postȩpy Dermatologii i Alergologii, vol. 32, no. 4, Aug. 2015, pp. 281–85. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.5114/pdia.2015.53047.

Farag, Azza Gaber Antar, et al. “Role of 11β HSD 1, Rs12086634, and Rs846910 Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms in Metabolic-Related Skin Diseases: A Clinical, Biochemical, and Genetic Study.” Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology, vol. 12, 2019, pp. 91–102. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.2147/CCID.S193156.

Hamilton, F. L., et al. “Laser and Other Light Therapies for the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris: Systematic Review.” The British Journal of Dermatology, vol. 160, no. 6, June 2009, pp. 1273–85. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09047.x.

Ibrahim, Adel A., et al. “IL1A (-889) Gene Polymorphism Is Associated with the Effect of Diet as a Risk Factor in Acne Vulgaris.” Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, vol. 18, no. 1, Feb. 2019, pp. 333–36. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.12516.

Juhl, Christian R., et al. “Dairy Intake and Acne Vulgaris: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 78,529 Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults.” Nutrients, vol. 10, no. 8, Aug. 2018, p. 1049. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10081049.

—. “Lactase Persistence, Milk Intake, and Adult Acne: A Mendelian Randomization Study of 20,416 Danish Adults.” Nutrients, vol. 10, no. 8, Aug. 2018, p. 1041. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10081041.

Lee, Young Ho, et al. “CTLA-4 and TNF-α Promoter-308 A/G Polymorphisms and ANCA-Associated Vasculitis Susceptibility: A Meta-Analysis.” Molecular Biology Reports, vol. 39, no. 1, Jan. 2012, pp. 319–26. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-011-0741-2.

Li, L., et al. “The Tumour Necrosis Factor-α 308G>A Genetic Polymorphism May Contribute to the Pathogenesis of Acne: A Meta-Analysis.” Clinical and Experimental Dermatology, vol. 40, no. 6, Aug. 2015, pp. 682–87. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/ced.12660.

Li, Wen-Hwa, et al. “Low-Level Red LED Light Inhibits Hyperkeratinization and Inflammation Induced by Unsaturated Fatty Acid in an in Vitro Model Mimicking Acne.” Lasers in Surgery and Medicine, vol. 50, no. 2, Feb. 2018, pp. 158–65. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/lsm.22747.

Navarini, Alexander A., et al. “Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Three Novel Susceptibility Loci for Severe Acne Vulgaris.” Nature Communications, vol. 5, June 2014, p. 4020. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5020.

Ragab, M., et al. “Association of Interleukin-6 Gene Promoter Polymorphism with Acne Vulgaris and Its Severity.” Clinical and Experimental Dermatology, vol. 44, no. 6, Aug. 2019, pp. 637–42. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/ced.13864.

Schröder, Jens-M. “Seeing Is Believing: Vitamin A Promotes Skin Health through a Host-Derived Antibiotic.” Cell Host & Microbe, vol. 25, no. 6, June 2019, pp. 769–70. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2019.05.011.

Szabó, K., et al. “Interleukin-1A +4845(G> T) Polymorphism Is a Factor Predisposing to Acne Vulgaris.” Tissue Antigens, vol. 76, no. 5, Nov. 2010, pp. 411–15. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0039.2010.01530.x.

Szabó, Kornélia, et al. “TNFα Gene Polymorphisms in the Pathogenesis of Acne Vulgaris.” Archives of Dermatological Research, vol. 303, no. 1, Jan. 2011, pp. 19–27. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-010-1050-7.

Wang, B., and Y. L. He. “Association of the TNF-α Gene Promoter Polymorphisms at Nucleotide -238 and -308 with Acne Susceptibility: A Meta-Analysis.” Clinical and Experimental Dermatology, vol. 44, no. 2, Mar. 2019, pp. 176–83. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/ced.13648.

Yang, Jian-Kang, et al. “TNF-308 G/A Polymorphism and Risk of Acne Vulgaris: A Meta-Analysis.” PloS One, vol. 9, no. 2, 2014, p. e87806. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087806.

Younis, S., and Q. Javed. “The Interleukin-6 and Interleukin-1A Gene Promoter Polymorphism Is Associated with the Pathogenesis of Acne Vulgaris.” Archives of Dermatological Research, vol. 307, no. 4, May 2015, pp. 365–70. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-014-1519-x.

Younis, Sidra, et al. “Resistin Gene Polymorphisms Are Associated with Acne and Serum Lipid Levels, Providing a Potential Nexus between Lipid Metabolism and Inflammation.” Archives of Dermatological Research, vol. 308, no. 4, May 2016, pp. 229–37. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-016-1626-y.