Key takeaways:

~ Fatigue can be a debilitating condition that plagues people at any age.

~ Research now points to the root cause of fatigue: elevated inflammatory cytokines.

~ Genetics research fills in the details on why and how inflammatory cytokines cause fatigue.

~ Understanding your genetic susceptibility to fatigue may help you to target the underlying causes.

Fatigue has a neuroimmune root cause:

Do you constantly feel tired, even when you know you slept well? Exhausted. Drained. Unable to function.

Fatigue is overwhelming tiredness, but not the same type of tiredness that you get from lots of physical activity or from lack of sleep. It can be temporary or long-lasting.

But what causes fatigue? Understanding why you feel fatigue – from a physiological standpoint – may set you on the right path toward feeling good again.

Fatigue in the physically ill patient is one of the most common and earliest non-specific symptoms of disease and can persist long after the medical condition has resolved. – Dantzer, et al. 2015[ref]

Inflammation as a root cause of fatigue:

Inflammation-induced fatigue is the concept that higher levels of inflammatory cytokine production cause the feeling of fatigue, aka chronic inflammation.

Fatigue is a totally normal response to inflammation. When your immune system is kicking into higher gear, this usually means you’re sick or wounded. And when you are sick or wounded, you should want to lie down and rest. This fatigue response to inflammation is something that all sick or hurt animals experience.

“…the behavior of sick animals and people is not a maladaptive response or the effect of debilitation, but rather an organized, evolved behavioral strategy to facilitate the role of fever in combating viral and bacterial infections.”[ref]

But what if you aren’t sick or hurt?

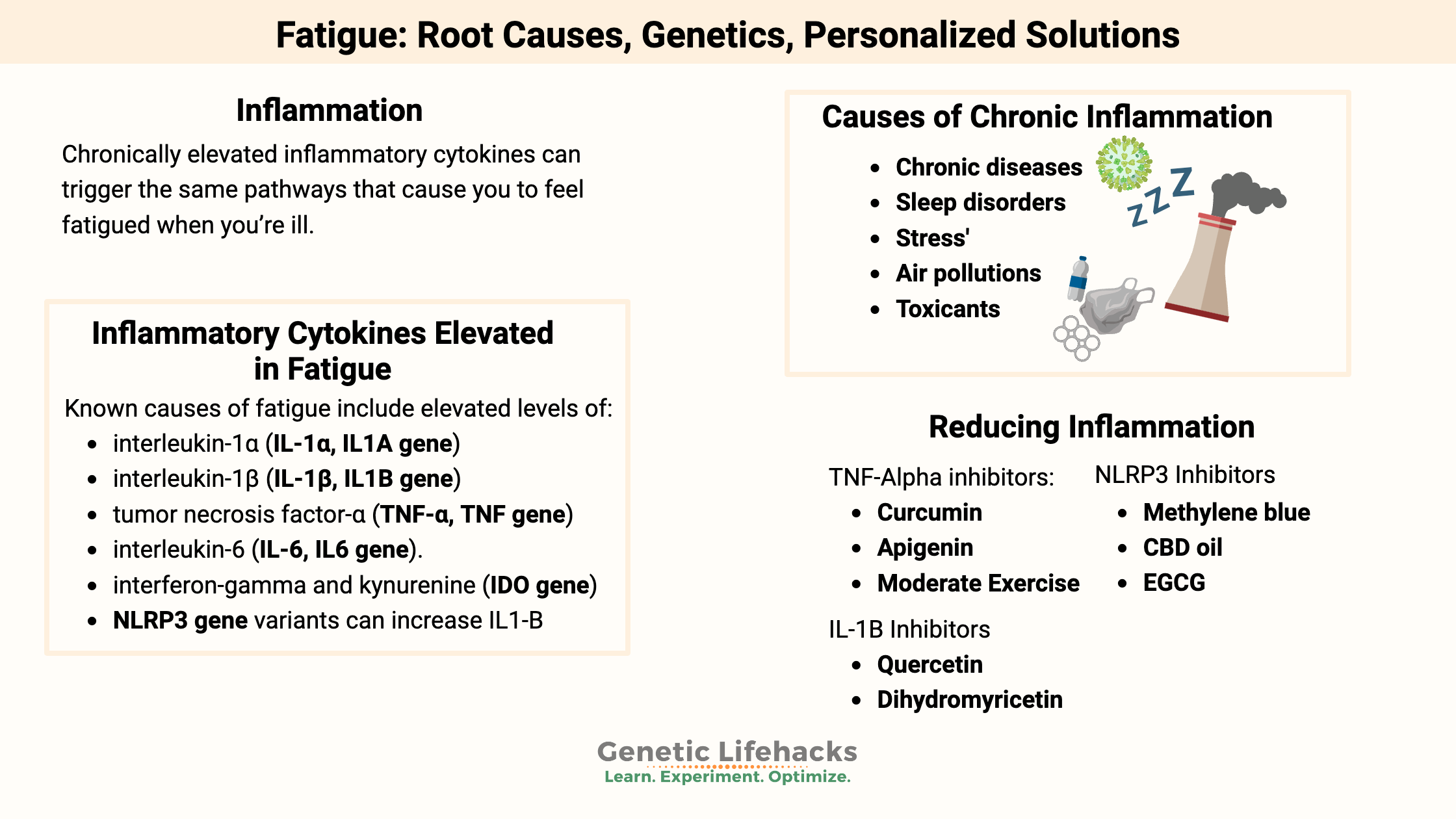

Chronically elevated inflammatory cytokines can trigger the same pathways that cause you to feel fatigued when you’re ill.

As one study puts it: “…sickness behaviour is not an accident of chronic inflammatory diseases but an adaptive program used during immune activation. Unfortunately, this program is switched-on considerably too long, during chronic conditions, sometimes lifelong.” – Korte, et al. 2019[ref]

Neuroinflammation: Fatigue really is all in your head…

Researchers have found that the brain is the “central regulator of fatigue perception”.[ref]

Inflammatory cytokines signal an inflammatory response in the body.

But how do elevated cytokines impact the brain? Elevated levels of cytokines in the body cannot easily pass the blood-brain barrier. Instead, the peripherally elevated cytokines can signal to the brain through a couple of pathways.

- The vagus nerve passes along the ‘inflammation’ signal to the brain from the abdomen.

- The trigeminal nerve is responsible for the brain knowing about infections in the teeth and oral cavity.

- At high enough levels, some inflammatory cytokines can gain access to the brain through transporters at the blood-brain barrier.[ref]

Getting Specific: What is chronic inflammation?

I’ve seen inflammation written about in vague terms on almost every alternative health or natural medicine type of website. Usually, the articles encourage eating the right diet (whatever ‘right’ diet is being promoted) or buying their supplements.

Let’s go into a little more depth here on the specifics of the inflammatory cytokines. Keep in mind that we will revisit all of these in the genetic variants section below.

Inflammatory cytokines elevated in fatigue:

Known causes of fatigue include elevated levels of:[ref][ref][ref][ref]

- interleukin-1α (IL-1α, IL1A gene)

- interleukin-1β (IL-1β, IL1B gene),

- tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α, TNF gene)

- interleukin-6 (IL-6, IL6 gene)

- interferon-gamma and kynurenine (IDO gene)

Additionally, the NLRP3 inflammasome can cause an increased or revved-up production of several of these cytokines.

Interleukin 1:

Interleukin 1 is part of the innate immune response. There are two main players here: IL-1alpha (IL-1α) and IL-1beta (IL-1β).

IL-1α is released when cells die, and it is present on the surface of immune system cells such as monocytes and B cells.

IL-1β is produced only in specific immune cells, including monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. When either of the IL-1 proteins binds to the IL-1 receptor, it causes a cascade of inflammatory events to happen.[ref]

Elevated IL-1 in the brain directly leads to ‘sickness behavior’, including fever and sleep. These behavior changes are due to altered dopamine synthesis via disruption of a precursor (BH4). Serotonin production can also decrease due to a shift in tryptophan to be used for kynurenine production. Reduced dopamine means that you aren’t motivated to do anything, and reduced serotonin may mean that you are less social and a little more irritable. AKA -Fatigue.

TNF-alpha:

TNF-alpha (tumor necrosis factor alpha) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine produced by macrophages, monocytes, and other cells. When a lot of TNF-alpha is produced by a cell, it is a signal that causes the cells to undergo cell death. Great when needed to destroy a tumor cell, but too much TNF-alpha is also linked to Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, psoriasis, arthritis, septic shock, and COPD.[ref]

There are two sides to TNF-alpha, though. When it docks with tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1 receptor), it initiates a whole cascade of inflammatory events including NF-kB activation or cell death. But there are also cases when TNF-alpha acts to modulate or reduce the immune response through binding to the TNFR2 receptor.

Elevated TNF-alpha levels are thought to be causal – or at least part of the cause – in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s, ALS, and Parkinson’s.[ref]

TNF-alpha inhibitor drugs are available and used for several chronic diseases. Side effects are the big drawback to these drugs, such as increased infections, fungal overgrowth, and potential increased cancer risk. For example, thalidomide is a TNF-alpha-reducing drug with a wide range of side effects, including severe birth defects.[ref]

Interferon-gamma and Kynurenine:

Interferon-gamma is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that is activated to fight off viral infections. It is the body’s first line of defense against certain viruses, and you need a good response to knock out a virus.

However, elevated interferon-gamma also shifts tryptophan metabolism away from serotonin/melatonin and towards the kynurenine pathway. It can result in higher levels of the neurotoxic metabolite quinolinic acid and a reduction in serotonin and melatonin.[ref]

NLRP3 inflammasome:

Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome causes an increase in other inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1B and IL-18. Basically, it revs up the immune response when activated by pathogens (such as viruses) or damage to cells (wounds, radiation, DNA or RNA that isn’t inside a cell where it should be, and misfolded proteins).

Chronic activation of NLRP3 is associated with atherosclerosis, MS, and diabetes.[ref][ref][ref]. Animal studies show that NLRP3 activation and its subsequent increase in IL-1B causes significantly more fatigue than without NLRP3.[ref]

Sources of chronic inflammation:

So what causes the elevation of these inflammatory cytokines all the time? Many reasons include autoimmune diseases, chronic conditions, sleep problems, stress, and exposure to environmental toxicants.

Chronic diseases and autoimmune conditions that involve chronic inflammation and fatigue include:[ref]

- Rheumatoid arthritis, with 50% or more reporting severe fatigue[ref][ref]

- Sjögren’s syndrome – higher IL-1 levels and fatigue[ref]

- Diabetes – 40% reporting fatigue[ref]

- Cancer- higher IL-1B and TNF-alpha linked to fatigue levels[ref][ref]

- Depressive disorder

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Parkinson’s disease

- Chronic liver disease[ref]

- NAFLD[ref]

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease[ref]

- Chronic infections (hepatitis, Epstein-Barr, Lyme, etc.)[ref]

In general, many autoimmune diseases (including the ones listed above) are characterized by aberrant inflammatory cytokine activation.[ref]

Often, though, fatigue due to chronic illness is exacerbated by additional causes…

Not always a single source!

If you don’t have a ‘chronic disease’ such as those listed above, other environmental factors may play a role in constantly feeling fatigued. While any one of these sources of inflammation (e.g., air pollution, mold, dental problems) is unlikely to cause constant fatigue, the combination of several could be.

Sleep and Circadian rhythm:

We all know that sleep is essential to overall health. But the timing of sleep also comes into play with chronic inflammation. The body’s 24-hour circadian rhythm controls when inflammatory cytokines are high and when they are low. When your circadian system is out of balance (staying up late, traveling across time zones, eating at odd hours), this can alter the rhythm and amplitude of cytokine production.[ref]

Stress and Inflammation:

We are built to respond to stressful situations periodically, such as running from a tiger or dealing with the death of a loved one. But repeated stresses cause an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines, including inflammatory cytokine elevation in the areas of the brain related to fatigue and anxiety.[ref]

Air pollution:

Increased air pollution exposure, especially to fine particulates, is linked to increased inflammation and increased oxidative stress.[ref] Specifically, higher levels of fine particulates correlate to higher levels of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-alpha in healthy young adults.[ref]

Toxicants:

Environmental exposure to toxicants is a vast topic. Some chemicals that we are exposed to daily are likely increasing oxidative stress and increasing inflammatory cytokines.[ref] But to some extent, there is an individualized response to detoxification (metabolism, elimination) of toxicants based on genetic variants in detoxification genes.

Toxicants that may cause increased oxidative stress and increased inflammatory cytokines include pesticides (organophosphates, paraquat, pyrethroids), flame retardants, metals (lead, mercury, aluminum, arsenic, manganese, cadmium, copper), plasticizers (BPA, phthalates), and PFOAs.[ref]

Lack of resolution of inflammation:

The resolution of inflammation is an active process that should go on at the same time that inflammation is initiated. This active process relies on specialized pro-resolving mediators, such as resolvin or maresin, which are synthesized from DHA and EPA (omega-3 fatty acids). Without sufficient DHA and EPA in your system at the time the inflammation began, you may not have had sufficient resolution of the inflammatory processes.

Related article: Read all about the Resolution of Inflammation and SPMs

Evidence showing inflammation causes fatigue:

Correlation vs. causation: Research is clear that elevated cytokine levels are found in people with fatigue, but that doesn’t necessarily prove that it is causal. The mechanism of action seems more than plausible, but let’s see what other evidence there is.

Animal studies clearly show that increasing certain cytokine levels consistently provokes fatigue-like behaviors.

Animal studies of the brain show changes that cause fatigue-like behavior:[ref]

- Increasing TNF-alpha interferes with noradrenaline secretion in certain parts of the brain.

- Elevated IL-1β along with IL-6 suppressed noradrenaline release.

- IL-2 can inhibit dopamine release from the striatum and noradrenaline release from the hypothalamus (regions of the brain).

Ok, so researchers can induce fatigue-like behavior in animals by increasing inflammation. But what about humans?

Studies show that interferon-alpha, when used as a drug to fight chronic hepatitis C, causes fatigue symptoms. Clinical trials using interferon-alpha show that a common side effect of interferon-alpha is persistent fatigue lasting more than 6-months.[ref][ref]

Endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide, LPS) exposure causes fatigue in people. A study exposed participants to low levels of endotoxin, which is a molecule found on the out membrane of some bacteria, or to placebo. The endotoxin exposure (without any bacteria) caused an immediate rise in IL-6. While this is expected in response to a bacterial infection, there was no actual infection involved. The researchers went further and did neurological tests, with the results showing a quick depression in mood along with the rise in IL-6. Additionally, in women, the neurological tests also showed “increases in social pain-related neural activity” in certain brain regions.[ref]

Research shows that inflammation also decreases neurotransmitter formation via reducing BH4 (tetrahydrobiopterin), which is needed for dopamine and serotonin production.[ref]

The other side of the equation also works: reducing inflammation causes a reduction in fatigue.

For people with rheumatoid arthritis, drugs that target inflammatory cytokines, such as anti-TNF agents, lead to a moderate improvement in fatigue scores.[ref] As one research study points out, “Fatigue in RA is prevalent, intrusive and disabling.”[ref] Thus, the reduction in an inflammatory cytokine causing a reduction in fatigue points directly to the inflammation as the cause of fatigue.

Fatigue Genotype Report:

Lifehacks: Diet, natural supplements, and lifestyle changes to stop fatigue

Fatigue can be a non-specific sign that something is wrong, and you should talk with your doctor about fatigue along with any other symptoms. For example, fatigue can be an initial symptom of cancer or autoimmune disease.[ref] Push for answers as to whether there are any indications of underlying diseases.

Dietary changes to target fatigue:

Anti-inflammatory diet:

Studies show that targeted dietary changes to reduce inflammation help fatigue in people with chronic diseases. A review sums it up: “clinical studies demonstrate that a balanced diet with whole grains high in fibers, polyphenol-rich vegetables, and omega-3 fatty acid-rich foods might be able to improve disease-related fatigue symptoms.”[ref]

While online diet gurus may argue the details of what constitutes an anti-inflammatory diet, the overarching theme is a diet that contains whole foods and not a lot of packaged, processed food.

High folate vegetable intake decreased TNF-alpha levels in women with the MTHFR C677T TT genotype.[ref]

Pro-resolving mediators:

If you eat a standard Western diet high in omega-6 fatty acids (e.g. corn oil, soybean oil) and low in omega-3 fatty acids (fish, seafood, pasture-raised eggs), you may not be getting sufficient DHA and EPA for resolving inflammation.

Related article: Read all about the Resolution of Inflammation and SPMs