Mood disorders such as depression and bipolar disorder are often thought of as being caused by a lack of neurotransmitters. Commercials on TV often make us think that depression is just a lack of a medication that increases neurotransmitters. But this is not the case for all people with mood disorders!

New research shows depression and bipolar disorder are linked with changes or disruptions in circadian genes. Also, genetic variants in the circadian clock genes can increase your susceptibility to mood disorders.

This article examines those connections and gives examples of just some of the many genetic variants in circadian genes that influence the risk of depression or bipolar disorder. It wraps up with specific solutions that may help if circadian rhythm disruption is at the root of your mood disorder.

What causes depression and bipolar disorder?

First, a couple of quick facts to set the stage:

- A major depressive disorder is defined as depression lasting more than a couple of weeks, affecting a person’s ability to function normally (e.g., loss of concentration, thoughts of death, problems sleeping). This affects about 16.2 million adults in the US (2016 data).[ref]

- Bipolar disorder affects 1-3% of the US population.[ref] This mood disorder involves episodes of manic highs and periods of depressive lows.

What is ‘circadian rhythm’?

Your circadian rhythm is a 24-hour cycle of your body’s molecular clock. Many of your biological processes rise and fall over the course of a day. The first thing that comes to mind for most is the sleep/wake cycle. In general, humans are diurnal – active during the day and sleep at night.

Other examples of your circadian rhythm include the fluctuation of body temperature, rise and fall of cortisol, nighttime melatonin production, etc., over the course of the day.

In fact, a lot of the proteins and enzymes that your body makes fluctuate over the course of 24 hours. For example, you don’t need to produce lactase (an enzyme that breaks down lactose in milk) at night when you are sleeping since you don’t drink or eat while you’re asleep. This is true for a lot of processes in the body — some need to occur while you are awake and active, and others need to occur when you are asleep.

Messing with your circadian rhythm has significant consequences on long-term health and mental well-being.

If you’ve traveled long distances, think back to the first time you experienced jet lag. I bet you felt awful – like being hit by a train. Jet lag makes me mentally foggy, physically drained and slightly ill – and my mood is usually pretty crappy. Now think of doing this on a regular (but smaller) basis, such as if your circadian rhythm is constantly out of sync. You can imagine how important circadian rhythm can be to physical and mental health.

Investigating the root cause of diseases: Genetic variants

One way researchers dig into the root causes of any disease or disorder is to look at the genetic variants that are found more often in people with the disease. Sometimes this is through sequencing specific variants to see if they are more common in patients. Other times they look at huge amounts of genetic data for a large population compared with a patient group. This genome-wide approach gives researchers a lot of clues about the various genes that affect a disease or disorder.

Genes that increase the probability of disease clearly point toward the mechanisms or pathways involved in the disease. In the case of mood disorders such as depression and bipolar disorder, there are quite a few genes involved in the core circadian clock that are statistically linked to these mood disorders.[ref]

One question genetic studies can help answer is cause vs. effect. It has long been known that sleep problems and circadian disruption are hallmarks of bipolar and depressive disorders. But it wasn’t known if the circadian disruption caused mood disorders or if the mood disorders caused the circadian disruption.

The studies showing that the genetic variants that cause changes to the circadian clock also significantly increase the risk of depression answer the cause vs. effect question. This clearly shows that disrupting the circadian clock can cause bipolar disease and depression.

But let me be clear: Circadian disruption is one of the causes. There are other causes of depression – and other genetic pathways that researchers have found. Knowing where your susceptibility lies can help you to understand which solutions may work best for you.

Clock genes and mood disorders:

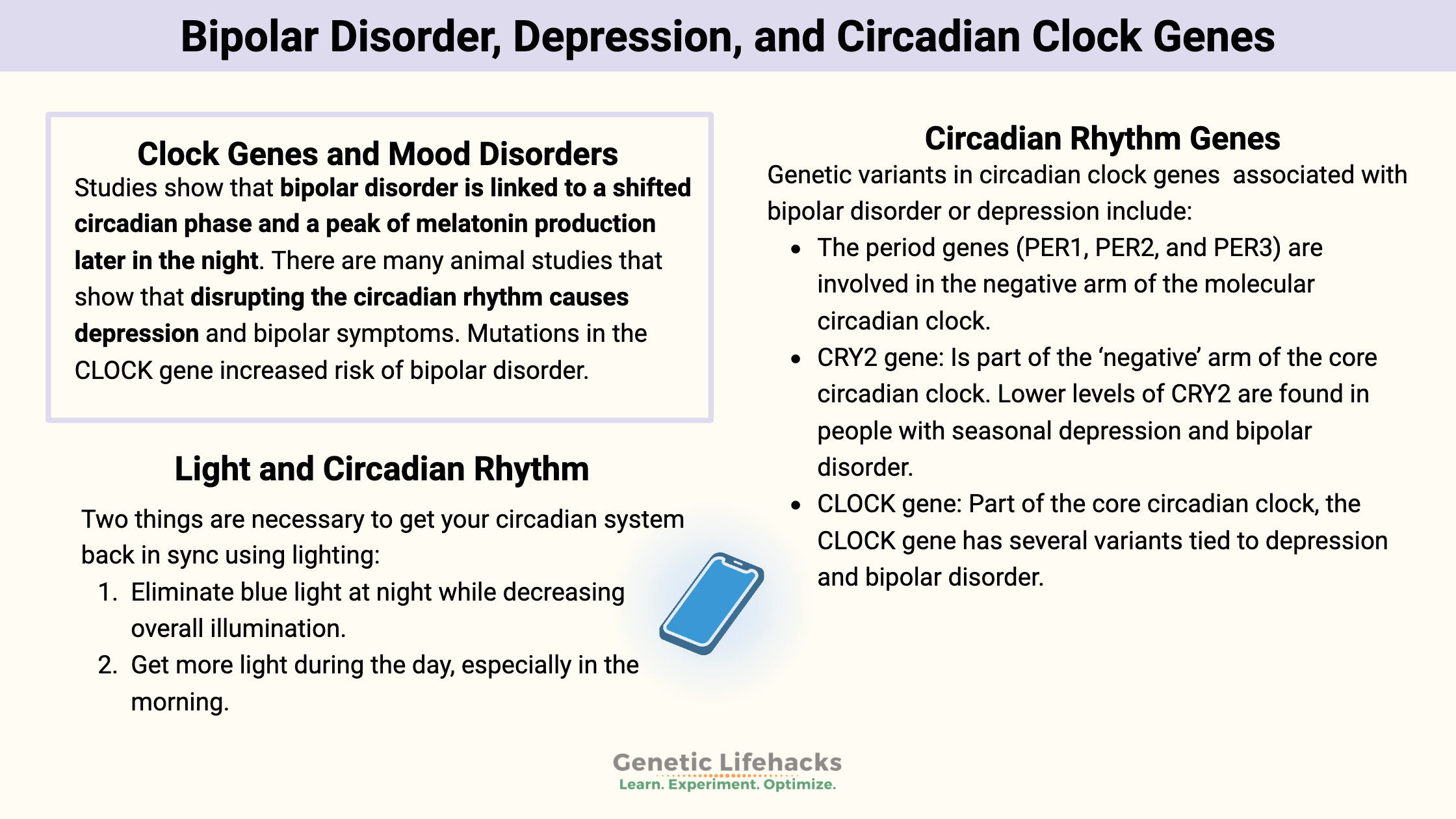

Studies show that bipolar disorder is linked to a shifted circadian phase and a peak of melatonin production later in the night. Along with shifted circadian gene expression, people with bipolar disorder also are more likely to have “irregularity of social rhythms, sleep/wake and activity patterns, and disruptions of social rhythms by life events”.[ref]

There are many animal studies that show that disrupting the circadian rhythm causes depression and bipolar symptoms. Mutations in the CLOCK gene produce a mouse model of bipolar disorder. And mouse experiments show that light at night, even dim light, is enough to cause changes to circadian rhythm and induce depressive symptoms.[ref][ref][ref][ref]

The human population studies also clearly show that bipolar disorder is both highly heritable (genetic) and related to circadian disruption.[ref] A recent (July 2021) study showed that bipolar disorder severity is strongly linked to the desynchronization of chronobiological rhythms.[ref]

Antidepressants and Circadian Clock Genes:

A lot of antidepressant prescription medications (both SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants) modify core circadian clock gene expression.[ref]

- Light experiments on animals (light at night, dim light during the day) cause depressive-like behaviors. The SSRI citalopram specifically works on depression caused by dim light at night but not on other depressive models.[ref]

- A human study shows that citalopram increases the “sensitivity of the circadian system to light”.[ref]

- Study shows that: “Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have a profound effect on the circadian system’s response to environmental light, which may impact treatment outcomes for patients depending on their habitual light exposure patterns.”[ref]

- A study using fluoxetine and different sleep quantities and timings over an 8-week trial. The conclusion was that 8 hours ‘time in bed’ was more effective than shorter sleep times that pushed patients to sleep earlier or later.[ref]

- A big study by 23andMe on bupropion (SSRI) efficacy found a genetic variant involved in circadian rhythm pathways.[ref]

- An animal study on how fluoxetine changes (lengthens) the circadian period.[ref]

- Another animal study used an SSRI, different feeding schedules, and different lighting schedules to find out how serotonin affects circadian clocks.[ref]

Are all mood disorders caused by circadian disruption?

No…But it can be a foundational part of these disorders for a number of people. There are always exceptions, so knowing your genetic variants is useful knowledge.

Carrying the genetic variants associated with mood disorders doesn’t mean you are destined to have problems with mood disorders — it just means you are more susceptible.

For most, mood disorders are a combo of genetic susceptibility and environmental factors (sleep, light, food, toxins, micronutrients, lifestyle, etc.).

If you carry some of the genetic variants below that are part of the core circadian clock system, then a likely factor influencing your mood disorder is your lifestyle choices that are disrupting your circadian rhythm. The good news is that you can modify this risk through simple changes in lifestyle.

Circadian Rhythm & Mood: Genotype Report

Lifehacks for changing mood:

If you are under the care of a physician or psychiatrist for one or more mood disorders, you should always talk to your doctor before making any changes. Many antidepressants work by modifying your circadian clock, so please consider these seemingly simple Lifehacks in the same context as trying an antidepressant drug.

The two biggest lifestyle factors for setting circadian rhythm are the timing of light exposure and the timing of eating. These are both considered ‘zeitgebers’ or ways of entraining the molecular circadian clock.

Light and Circadian Rhythm:

Light is foundational to your body’s circadian rhythm. For all of human history, the sun came up in the morning and set at night. Modern electrical lighting is messing with our circadian system. While we are resilient beings, chronic exposure to light at night is decreasing melatonin levels and disturbing our molecular clock.

Specifically, our eyes contain a photoreceptor that is sensitive to light in the blue spectrum (around 480 nm). Light at this wavelength causes signals from the retina to our brain, saying that it is daytime. All fine and dandy until the advent of color TVs, laptops, smartphones, and LED / CFL / fluorescent light bulbs. (The old-fashioned light bulbs that were yellowish in color didn’t emit much light in the blue spectrum.)

Two things are necessary to get your circadian system back in sync using lighting:

- Eliminate blue light at night while decreasing overall illumination.

- Get more light during the day, especially in the morning.

1) Eliminating blue light at night:

Related Articles and Topics:

Tryptophan

Tryptophan is an amino acid that the body uses to make serotonin and melatonin. Genetic variants can impact the amount of tryptophan that is used for serotonin. This can influence mood, sleep, neurotransmitters, and immune response.

Is inflammation causing your depression or anxiety?

Research over the past two decades clearly shows a causal link between increased inflammatory markers and depression. Genetic variants in the inflammatory-related genes can increase the risk of depression and anxiety.

More studies to read:

Aberrant light directly impairs mood and learning through melanopsin-expressing neurons.

Chronic unpredictable stress induces a reversible change of PER2 rhythm in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. To create an animal model of depression, researchers can use ‘chronic unpredictable stress’. This then causes a reduction in the amount of one of the core circadian clock genes (PER2). Researchers were able to reverse this reduction (and the depression) by using a tricyclic antidepressant.

Time of Administration of Acute or Chronic Doses of Imipramine Affects its Antidepressant Action in Rats. This animal study found that the timing of taking the tricyclic antidepressant Tofranil matter a lot as far as its effectiveness.

Prospective, Open Trial of Adjunctive Triple Chronotherapy for the Acute Treatment of Depression in Adolescent Inpatients. This is one of several studies on humans using ‘triple chronotherapy’ for the remission of depression and bipolar disorder. In this study, 84% of the teens with moderate to severe depression were in remission for 1+ month after treatment. The treatment consists of resetting the circadian clock through one night of sleep deprivation and then three nights of controlled sleep timing and bright morning lighting.

Adjunctive Triple Chronotherapy (Combined Total Sleep Deprivation, Sleep Phase Advance, and Bright Light Therapy) Rapidly Improves Mood and Suicidality in Suicidal Depressed Inpatients: An Open-Label Pilot Study. Another study used triple chronotherapy for suicidal patients who had been committed to a psychiatric hospital. This study showed a 60% remission rate, which is pretty darn impressive.