Key Takeaways:

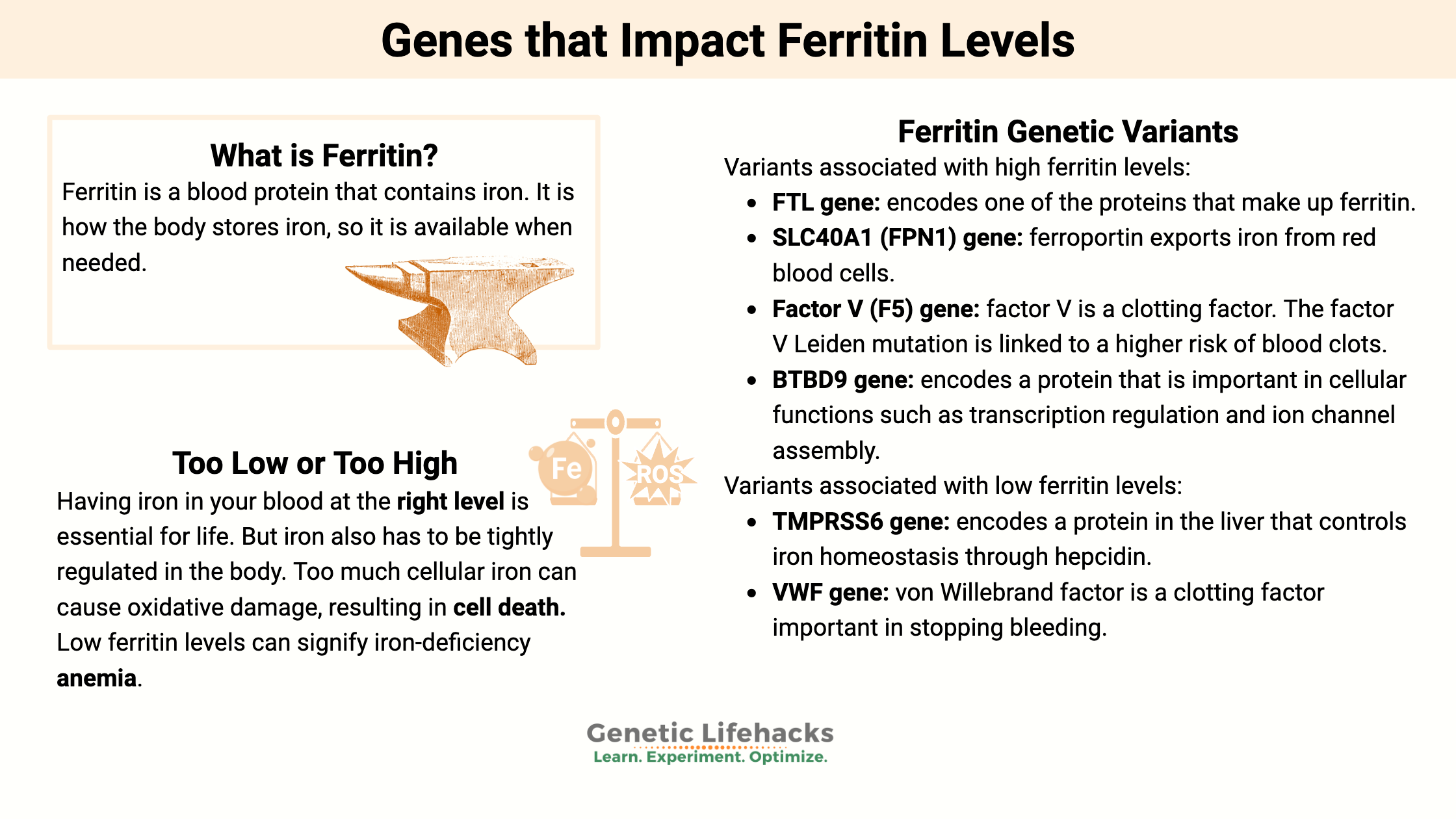

~ Iron is essential for carrying oxygen throughout the body, and ferritin is a protein that stores iron so that it is available when needed.

~ Serum ferritin levels are one way of measuring iron in your body, and high or low lab results can indicate an underlying problem.

~ Genetic variants (SNPs) impact your baseline ferritin levels and your susceptibility to problems with low or high ferritin.

What is ferritin?

Ferritin is a blood protein that contains iron. It is how the body stores iron, so it is available when needed.

Having iron in your blood at the right level is essential for life; however, iron also has to be tightly regulated in the body. Too much cellular iron can cause oxidative damage, resulting in cell death.[ref]

Iron is also essential for many pathogens – bacteria, malaria, etc. Thus, your body regulates iron as a way to keep pathogens from being able to survive.[ref]

Ferritin, the iron storage protein, is primarily found in the liver, bone marrow, muscles, and spleen. About 70-80% of your iron is stored as ferritin when you are healthy.[ref] This iron storage gives the body access to an adequate supply whenever needed.

Each ferritin protein is made up of subunits that come together to form the structure. Within this structure, iron is deposited. “A single ferritin molecule of this type can hold up to 4300 iron ions in its central cavity”. In addition to iron, ferritin also holds phosphate.[ref]

Ferritin blood tests: normal serum ranges

According to the Mayo Clinic, the normal range for a ferritin test is:[ref]

- For men, 24 to 336 mg/l (or ng/mL)

- For women, 11 to 307 mg/l

You may notice that the normal range varies a bit depending on the testing company. For example, Mount Sinai has the normal range as 12 -300 ng/mL for men and 12 – 150 ng/mL.

Low or high ferritin levels:

Low ferritin levels can signify iron-deficiency anemia, but it is also found in other conditions. Your doctor will likely do additional tests to determine the cause for you. For example, testing for transferrin saturation and serum iron levels can shed light on the root cause.

According to the CDC, iron status is defined using the following criteria:[ref]

| Iron Status | Stored Iron (ferritin) | Transport iron (transferrin saturation) | Functional iron (serum iron |

|---|---|---|---|

| iron-deficiency anemia | low | low | low |

| iron-deficiency erythropoiesis | low | low | normal |

| iron depletion | low | normal | normal |

| iron overload | high | high | normal |

Causes of low ferritin:

Ferritin is the storage protein for iron in the body, and a common cause of low ferritin is low iron levels.[ref]

Blood loss or low iron intake are the leading causes of low ferritin levels in healthy people. Other causes can include inflammatory bowel disease or celiac disease, which decreases iron absorption.[ref]

Symptoms of iron deficiency anemia include:[ref]

- fatigue or weakness

- pale skin

- fast heartbeat, shortness of breath

- headache, dizziness, lightheadedness

- cold hands and feet

- inflammation or soreness of your tongue (burning tongue, cracks)

- pica (craving to eat dirt, ice)

Causes of high ferritin:

Several diseases cause higher ferritin levels.

- Hemochromatosis, a genetic reason for iron build-up (check your genes here)

- Porphyria — A group of disorders caused by an enzyme deficiency that affects your nervous system and skin

- Inflammatory disorders such as Rheumatoid arthritis

- Liver disease

- Hyperthyroidism

- Blood cancers (leukemia and Hodgkin’s lymphoma)

High ferritin levels can also be caused by:

- Multiple blood transfusions

- Alcohol abuse

- Excessive supplemental iron

Inflammation usually causes ferritin levels to rise. Inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNFα, increase the creation of the ferritin molecule. Excess ROS, such as hydrogen peroxide, can also increase ferritin.[ref]

Chronically elevated inflammatory cytokines, such as is seen in periodontitis (gum disease), are associated with higher serum ferritin levels. Higher ferritin levels are also found, on average, in people with diabetes.[ref]

Proteins that regulate iron:

When looking at the genetic variants that link to higher ferritin levels, we must go beyond just the genes that encode the ferritin proteins. Instead, the main genetic drivers of higher ferritin averages include other proteins involved in regulating iron levels.

Here’s a quick overview:

Ferroportin is the protein responsible for transporting iron out of cells. It is found in the small intestines, liver cells, and macrophages (a white blood cell type). For example, in the small intestines, it regulates the transport of iron from food into the bloodstream. Ferroportin is an important regulator when there is too much iron available, inflammation, or a lot of red blood cells being produced.[ref]

Hepcidin is another iron regulatory protein. It regulates how much iron can circulate by inhibiting ferroportin. In this way, hepcidin essentially regulates how much iron is absorbed in the intestines and allowed into circulation. During times of acute inflammation, hepcidin levels rise, causing iron levels to fall.[ref]

Transferrin is a glycoprotein that transports iron in the blood plasma. The TF gene encodes transferrin, and it is produced in the liver. Transferrin binds to iron (usually in the intestines) and transports it until it encounters a transferrin receptor (on red blood cells). It binds with the transferrin receptor and releases iron ions.

Transferrin levels decrease in inflammation, cancer, and some diseases (acute-phase protein that decreases instead of increasing)

Ferritin Genotype Report:

Lifehacks: Diet, Supplements, and Ferritin Levels

Always get a blood test to determine your iron levels before supplementing. Iron is essential but not benign. You definitely don’t want to overdo it with supplemental iron. Talk with a doctor or pharmacist if you have any questions about iron, especially regarding supplemental iron interactions with other medications.

According to the CDC, adults need at least 8 mg of iron per day. Premenopausal women need around 18mg/day, depending on blood loss due to menstruation.

How can you increase ferritin levels?

If you are low in iron, there are several dietary changes that may help to increase your iron levels.

Foods high in iron include[ref]:

| Food | Milligrams/serving | Percent DV* |

| Breakfast cereals, fortified with 100% of the DV for iron, 1 serving | 18 | 100 |

| Oysters, eastern, cooked with moist heat, 3 ounces | 8 | 44 |

| White beans, canned, 1 cup | 8 | 44 |

| Chocolate, dark, 45%–69% cacao solids, 3 ounces | 7 | 39 |

| Beef liver, pan-fried, 3 ounces | 5 | 28 |

| Lentils, boiled and drained, ½ cup | 3 | 17 |

| Spinach, boiled and drained, ½ cup | 3 | 17 |

| Tofu, firm, ½ cup | 3 | 17 |

| Kidney beans, canned, ½ cup | 2 | 11 |

| Sardines, Atlantic, canned in oil, drained solids with bone, 3 ounces | 2 | 11 |

| Chickpeas, boiled and drained, ½ cup | 2 | 11 |

| Tomatoes, canned, stewed, ½ cup | 2 | 11 |

| Beef, braised bottom round, trimmed to 1/8” fat, 3 ounces | 2 | 11 |

| Potato, baked, flesh and skin, 1 medium potato | 2 | 11 |

| Cashew nuts, oil roasted, 1 ounce (18 nuts) | 2 | 11 |

| Green peas, boiled, ½ cup | 1 | 6 |

| Chicken, roasted, meat and skin, 3 ounces | 1 | 6 |

| Rice, white, long-grain, enriched, parboiled, drained, ½ cup | 1 | 6 |

| Bread, whole wheat, 1 slice | 1 | 6 |

| Bread, white, 1 slice | 1 | 6 |

| Raisins, seedless, ¼ cup | 1 | 6 |