Key Takeaways:

~Raynaud’s syndrome causes white or blue fingertips in the cold or during stressful situations.

~Raynaud’s is caused by vasoconstriction that decreases blood flow to the extremities.

~ Genetics plays a role in who gets Raynaud syndrome.

~ Understanding your genes can help you choose the natural solution right for you.

Raynaud’s Syndrome

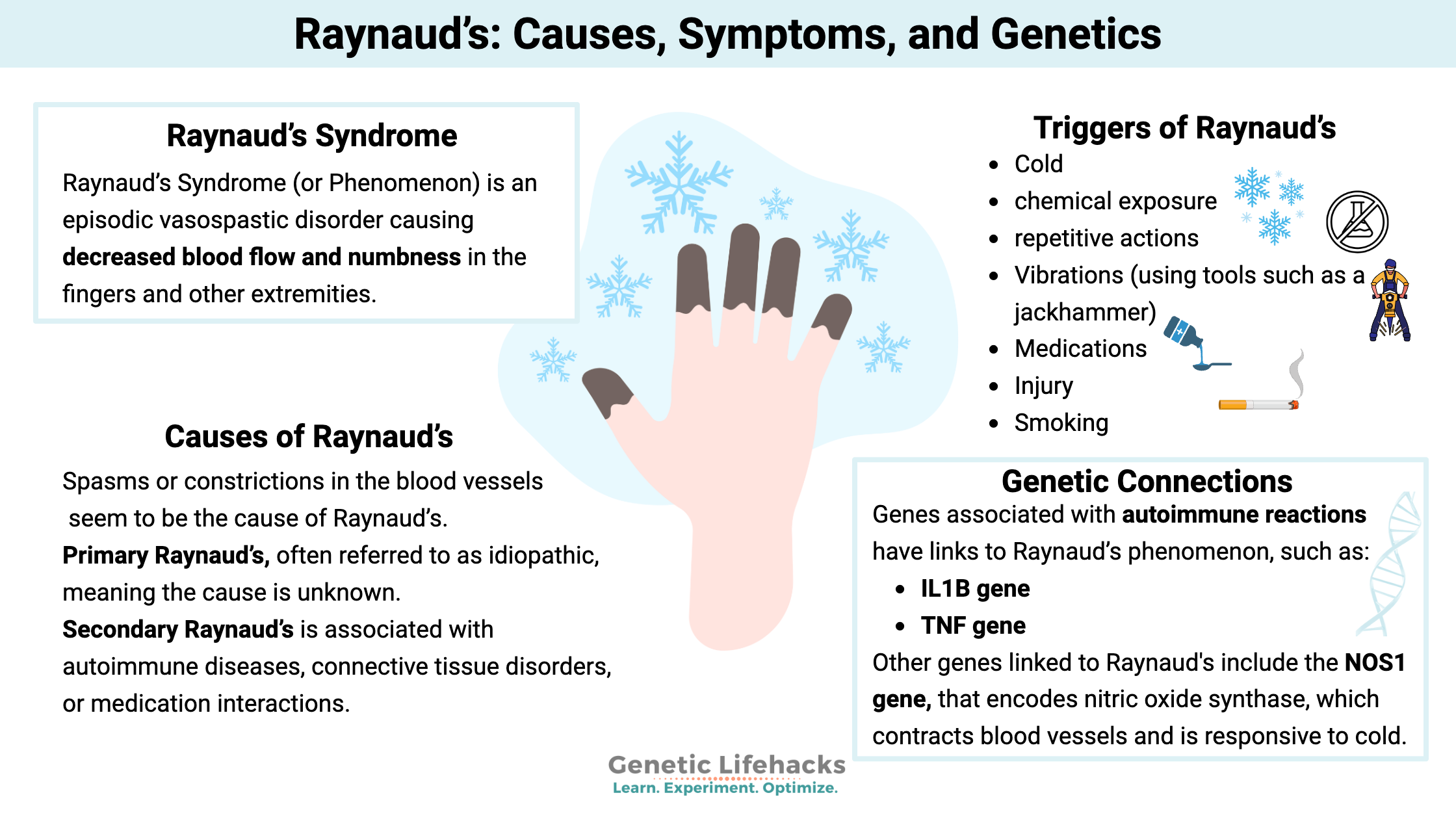

Raynaud’s Syndrome (or Phenomenon) is an episodic vasospastic disorder causing decreased blood flow and numbness in the fingers and other extremities.

As the blood vessels constrict, it reduces the blood flow to the fingers or other extremities. Cold or stress (physical or mental) can trigger the blood vessel constriction.

Women are more likely than men to have Raynaud’s syndrome. Some researchers report almost 1 in 5 women have Raynaud’s.[ref]

Often Raynaud’s occurs along with other underlying conditions, such as autoimmune diseases or connective tissue disorders. Sometimes Raynaud’s Phenomenon can be ‘primary’ and occur alone.

Many people with Raynaud’s also have migraines, which may link to vasoconstriction.

Symptoms of Raynaud’s

The drastic color changes in the extremities are a tell-tale sign of this syndrome. It is the first symptom that most people notice with Raynaud’s. The tips of the fingers turn very white from the decreased blood flow and then appear blue or cyanotic with cold or stress. These changes are followed by the fingers turning red when warmed up and blood flow returns (or no longer stressed).

Doctors can use cold provocation or place the hands in cold, to cause the vessels to constrict. Infrared thermography can then determine the extent of the changes in blood flow to the extremities.[ref]

While it is easy to think of Raynaud’s as just ‘fingers turning white in the cold’, restricting blood to the extremities can be very painful and can cause irreversible tissue damage in severe cases.[ref]

Causes of Raynaud’s syndrome

Spasms or constrictions in the blood vessels seem to be the cause of Raynaud’s. It is an exaggeration of the typical response of blood vessels to either cold or emotional stress.[ref]

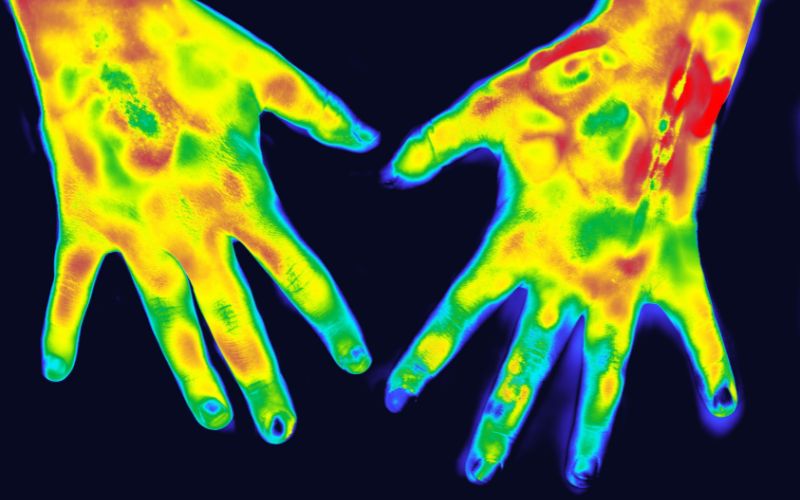

Some researchers theorize that the cause of the spasms in the blood vessels comes from the impaired functioning of the adrenergic receptors in the vascular muscle cells. Three types of adrenergic receptors are responsible for constricting or relaxing the muscles surrounding the blood vessels. One adrenergic receptor subtype activates with cold and norepinephrine (noradrenaline), which also releases stressful situations.[ref]

The blood vessel spasms can be ‘primary’ or ‘secondary’.

Primary Raynaud’s, often referred to as idiopathic, meaning the cause is unknown. This unknown reason causes the overreaction of the blood vessel constriction to the extremities.

Secondary Raynaud’s is associated with autoimmune diseases, connective tissue disorders, or medication interactions.

Autoimmune diseases that are more likely to cause Raynaud’s include:[ref]

- systemic sclerosis

- systemic lupus erythematosus

- Sjögren’s syndrome

- fibromyalgia[ref]

Raynaud’s can be one of the first symptoms of certain autoimmune diseases, giving doctors and patients a ‘heads-up’ to look for diseases early.[ref]

Related articles: Lupus genes, Sjogren’s genes, Fibromyalgia genes

Talk with your doctor if you have Raynaud’s. Getting a test for specific autoantibodies in autoimmune diseases may help you get quicker treatment.

For example, antinuclear antibodies often help diagnose these autoimmune diseases (lupus, Sjögren’s, and systemic sclerosis). Other antibodies can indicate antisynthetase syndrome. “The antisynthetase syndrome (ASSD) is an autoimmune disorder characterized by myositis, arthritis, mechanic’s hands, fever, Raynaud phenomenon, and interstitial lung disease (ILD).”[ref]

Raynaud’s phenomenon is also associated with connective tissue disorders, such as Ehlers Danlos Syndromes.[ref][ref]

Related Article: Genetics and Ehlers Danlos Syndrome

Triggers of Raynaud’s Syndrome

The reduction of blood flow in the extremities seen in Raynaud’s phenomenon can be triggered by:[ref]

- Cold

- chemical exposure

- repetitive actions

- Vibrations (using tools such as a jackhammer)

- Medications

- Injury

- Smoking

Cold: A natural reaction to cold is for blood vessels in the fingers and toes to constrict. But in Raynaud’s, the constriction doesn’t ease and is more exaggerated than normal.

Medications: Several classes of medications can cause Raynaud’s phenomenon. The highest risk occurs with cisplatin and bleomycin, but β-adrenoceptor blockers (a.k.a beta-blockers) are a very common medication that may cause Raynaud’s in some people. For others, migraine medications, such as triptans, have links to Raynaud’s.[ref]

Vibration: Vibration white finger is often the term applied to Raynaud’s syndrome caused by mechanical vibration. People who work with vibrating machinery are at about a 4-fold increased risk of Raynaud’s.[ref]

Chemical exposure: In addition to medications, chemicals such as vinyl chloride can also cause Raynaud’s.[ref] Arsenic exposure is also associated with Raynaud’s.[ref]

Related article: Arsenic detoxification genes

Why is Raynaud’s found more commonly in women?

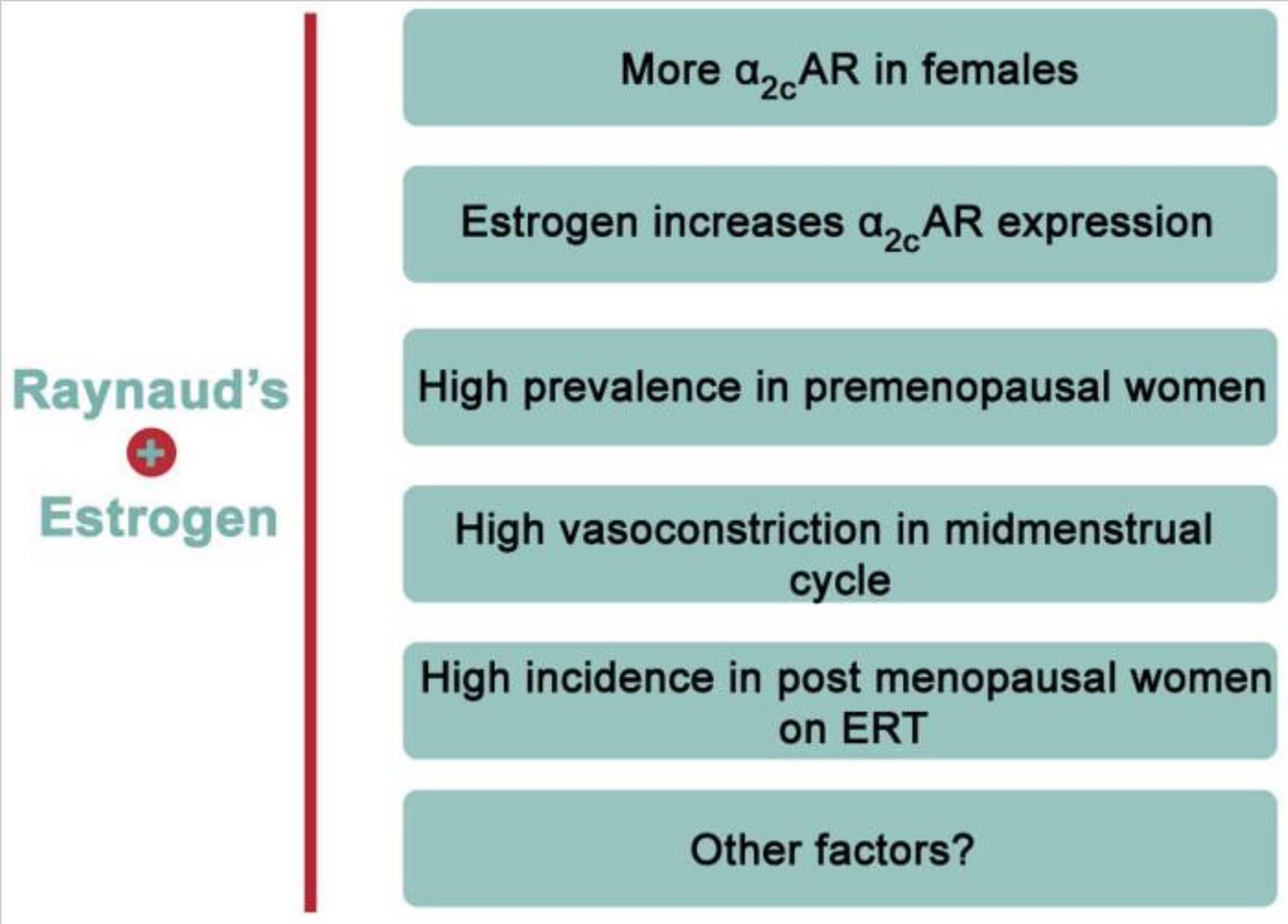

Researchers think that Raynaud’s may be more common in premenopausal women due to estrogen’s impact on vasoconstriction through the α2C-AR (alpha(2C)-adrenoceptors) receptors located in blood vessels. Estrogen also plays a role in regulating body temperature. Research shows that post-menopausal women on estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy also have a higher incidence of Raynaud’s.[ref][ref]

Is Raynaud’s syndrome genetic?

Research shows that Raynaud’s runs in families and seems to be about 30-55% hereditary.[ref][ref][ref]

This means that genetic variants increase the susceptibility to Raynaud’s, but there isn’t a single gene mutation or variant that causes it by itself. Like most conditions, Raynaud’s is likely due to genetic susceptibility combined with a triggering factor.

The genetics section below highlights some genetic variants associated with an increased relative risk of Raynaud’s.

In addition, a genome-wide association study recently found two genes that likely play a role in Raynaud’s. While these GWAS variants only increase the relative risk of Raynaud’s a little bit, the study points to a reason or mechanism for the disease. The genes identified included ADRA2A and IRX1.[ref]

The ADRA2A gene encodes the α2A-adrenoreceptor, which is part of how the body modulates vasoconstriction in response to stress in the peripheral nervous system (e.g. cold). The variants in the gene are thought to cause increased expression and therefore an increased vasoconstriction response in the periphery, such as in the hands and feet. (Variants in another adrenoreceptor, ADRA1A, are linked to faiting more easily.)

The IRX1 gene is expressed in skeletal muscles and arteries. It is believed to be involved in embryonic development and the way that cells differentiate.

Raynaud’s syndrome and COVID-19 vaccination

Case reports of Raynaud’s after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination include a 31-year-old woman with a new onset of Raynaud’s after the vaccine.[ref] The VAERS database also lists cases of Raynaud’s coinciding with the SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. To see this reference, go to medalerts.org and search for Raynaud’s symptoms and COVID-19 vaccines.

Keep in mind that it could be entirely coincidental for Raynaud’s to occur post-vaccine.

Raynaud’s Syndrome Genotype Report

Lifehacks:

Treatments for Raynaud’s

Keep your fingers warm in the cold weather :-)

This advice was given for Raynaud’s in 1908 and is still valid today. Wear gloves, and take finger heaters with you. They even make little rechargeable heaters that you can put in your pockets in cold weather.

Talk with your doctor about medication options for Raynaud’s phenomenon. If you aren’t already diagnosed with an autoimmune disease, ask whether this could be an indicator of an underlying autoimmune condition.

Stop smoking. Smoking promotes vasoconstriction and may make Raynaud’s worse.

Natural supplements that are backed by research for Raynaud’s:

Related Articles and Topics:

Nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS3): Heart Health, Blood Pressure, and Healthy Aging

References:

Brisset, Marion, et al. “Biallelic Mutations in Tenascin-X Cause Classical-like Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome with Slowly Progressive Muscular Weakness.” Neuromuscular Disorders: NMD, vol. 30, no. 10, Oct. 2020, pp. 833–38. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmd.2020.09.002.

Chen, Qingsong, et al. “HTR1B Gene Variants Associate with the Susceptibility of Raynauds’ Phenomenon in Workers Exposed Hand-Arm Vibration.” Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation, vol. 63, no. 4, Oct. 2016, pp. 335–47. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3233/CH-152021.

Curtiss, P., et al. “The Clinical Effects of L‐arginine and Asymmetric Dimethylarginine: Implications for Treatment in Secondary Raynaud’s Phenomenon.” Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, vol. 33, no. 3, Mar. 2019, pp. 497–503. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.15180.

Eid, A. H., et al. “Estrogen Increases Smooth Muscle Expression of Alpha2C-Adrenoceptors and Cold-Induced Constriction of Cutaneous Arteries.” American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology, vol. 293, no. 3, Sept. 2007, pp. H1955-1961. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00306.2007.

Fardoun, Manal M., et al. “Raynaud’s Phenomenon: A Brief Review of the Underlying Mechanisms.” Frontiers in Pharmacology, vol. 7, Nov. 2016, p. 438. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2016.00438.

—. “Raynaud’s Phenomenon: A Brief Review of the Underlying Mechanisms.” Frontiers in Pharmacology, vol. 7, Nov. 2016, p. 438. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2016.00438.

—. “Raynaud’s Phenomenon: A Brief Review of the Underlying Mechanisms.” Frontiers in Pharmacology, vol. 7, Nov. 2016, p. 438. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2016.00438.

Freedman, R. R., and M. D. Mayes. “Familial Aggregation of Primary Raynaud’s Disease.” Arthritis and Rheumatism, vol. 39, no. 7, July 1996, pp. 1189–91. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1002/art.1780390717.

Garner, Rozeena, et al. “Prevalence, Risk Factors and Associations of Primary Raynaud’s Phenomenon: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies.” BMJ Open, vol. 5, no. 3, Mar. 2015, p. e006389. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006389.

Haque, Ashraful, and Michael Hughes. “Raynaud’s Phenomenon.” Clinical Medicine, vol. 20, no. 6, Nov. 2020, pp. 580–87. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmed.2020-0754.

Herrick, Ariane L. “Evidence-Based Management of Raynaud’s Phenomenon.” Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease, vol. 9, no. 12, Dec. 2017, pp. 317–29. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1177/1759720X17740074.

—. “Evidence-Based Management of Raynaud’s Phenomenon.” Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease, vol. 9, no. 12, Dec. 2017, pp. 317–29. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1177/1759720X17740074.

Hirankarn, N., et al. “Genetic Susceptibility to SLE Is Associated with TNF-Alpha Gene Polymorphism -863, but Not -308 and -238, in Thai Population.” International Journal of Immunogenetics, vol. 34, no. 6, Dec. 2007, pp. 425–30. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-313X.2007.00715.x.

Kaufman, Carolyn S., and Merlin G. Butler. “Mutation in TNXB Gene Causes Moderate to Severe Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome.” World Journal of Medical Genetics, vol. 6, no. 2, May 2016, pp. 17–21. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.5496/wjmg.v6.i2.17.

Khouri, Charles, et al. “Drug‐induced Raynaud’s Phenomenon: Beyond Β‐adrenoceptor Blockers.” British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, vol. 82, no. 1, July 2016, pp. 6–16. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12912.

Koulouri, Vasiliki, et al. “The Role of Novel Autoantibodies in the Diagnostic Approach and Prognosis of Patients with Raynaud’s Phenomenon.” Mediterranean Journal of Rheumatology, vol. 31, no. 4, Dec. 2020, pp. 427–29. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.31138/mjr.31.4.427.

—. “The Role of Novel Autoantibodies in the Diagnostic Approach and Prognosis of Patients with Raynaud’s Phenomenon.” Mediterranean Journal of Rheumatology, vol. 31, no. 4, Dec. 2020, pp. 427–29. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.31138/mjr.31.4.427.

Lindberg, Lotte, et al. “Infrared Thermography as a Method of Verification in Raynaud’s Phenomenon.” Diagnostics, vol. 11, no. 6, May 2021, p. 981. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11060981.

Munir, Sabrina, et al. “Association of Raynaud’s Phenomenon with a Polymorphism in the NOS1 Gene.” PLoS ONE, vol. 13, no. 4, Apr. 2018, p. e0196279. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196279.

Nakamura, H., et al. “Blood Endothelin-1 and Cold-Induced Vasodilation in Patients with Primary Raynauld’s Phenomenon and Workers with Vibration-Induced White Finger.” International Angiology: A Journal of the International Union of Angiology, vol. 22, no. 3, Sept. 2003, pp. 243–49.

Nilsson, Tohr, et al. “Hand-Arm Vibration and the Risk of Vascular and Neurological Diseases—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” PLoS ONE, vol. 12, no. 7, July 2017, p. e0180795. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180795.

Paradowska-Gorycka, Agnieszka, et al. “Interferons (IFN-A/-B/-G) Genetic Variants in Patients with Mixed Connective Tissue Disease (MCTD).” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 8, no. 12, Nov. 2019, p. E2046. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8122046.

Ponce-Gallegos, Marco Antonio, et al. “Genetic Susceptibility to Antisynthetase Syndrome Associated With Single-Nucleotide Variants in the IL1B Gene That Lead Variation in IL-1β Serum Levels.” Frontiers in Medicine, vol. 7, 2020, p. 547186. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.547186.

—. “Genetic Susceptibility to Antisynthetase Syndrome Associated With Single-Nucleotide Variants in the IL1B Gene That Lead Variation in IL-1β Serum Levels.” Frontiers in Medicine, vol. 7, 2020, p. 547186. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.547186.

Rosato, Edoardo, et al. “The Treatment with N-Acetylcysteine of Raynaud’s Phenomenon and Ischemic Ulcers Therapy in Sclerodermic Patients: A Prospective Observational Study of 50 Patients.” Clinical Rheumatology, vol. 28, no. 12, Dec. 2009, pp. 1379–84. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-009-1251-7.

Scolnik, M., et al. “Symptoms of Raynaud’s Phenomenon (RP) in Fibromyalgia Syndrome Are Similar to Those Reported in Primary RP despite Differences in Objective Assessment of Digital Microvascular Function and Morphology.” Rheumatology International, vol. 36, no. 10, Oct. 2016, pp. 1371–77. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-016-3483-6.

Shepherd, Anthony I., et al. “‘Beet’ the Cold: Beetroot Juice Supplementation Improves Peripheral Blood Flow, Endothelial Function, and Anti-Inflammatory Status in Individuals with Raynaud’s Phenomenon.” Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 127, no. 5, Nov. 2019, pp. 1478–90. journals.physiology.org (Atypon), https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00292.2019.

Smyth, A. E., et al. “A Case-Control Study of Candidate Vasoactive Mediator Genes in Primary Raynaud’s Phenomenon.” Rheumatology (Oxford, England), vol. 38, no. 11, Nov. 1999, pp. 1094–98. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/38.11.1094.

Umemoto, Kanae, et al. “Acupuncture Point ‘Hegu’ (LI4) Is Close to the Vascular Branch from the Superficial Branch of the Radial Nerve.” Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, vol. 2019, June 2019, p. e6879076. www.hindawi.com, https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6879076.

Urban, Nikolaus, et al. “Raynaud’s Phenomenon after COVID-19 Vaccination: Causative Association, Temporal Connection, or Mere Bystander?” Case Reports in Dermatology, vol. 13, 2021, pp. 450–56. www.karger.com, https://doi.org/10.1159/000519147.