Key takeaways:

~ POTS (postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome) is a problem with how the autonomic nervous system regulates heart rate, causing it to increase suddenly when standing.

~ Genetic variants can make you more susceptible to the condition, and understanding your genes can help you target the right therapy.

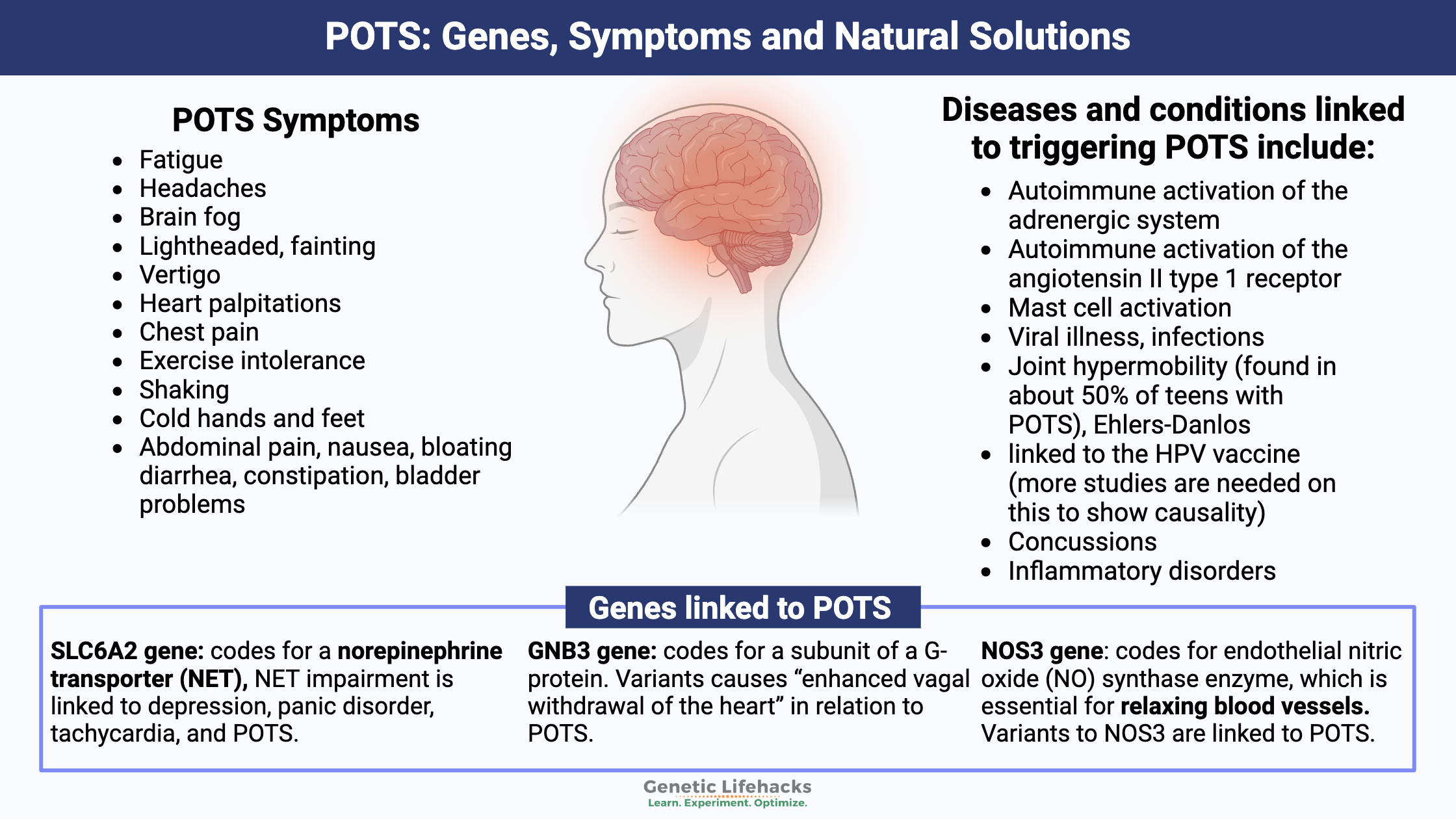

~ Genes linked to POTS include HLA genes, SLC6A2 (norepinephrine transporter), GNB3, and NOS3 (nitric oxide synthase).

~ Epigenetic modifications, especially those affecting the norepinephrine transporter, are also associated with POTS.

Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS): Background Science, Dysautonomia

POTS (postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome) is a problem with how your autonomic nervous system regulates heart rate when you change position, such as going from lying down to standing up. It is classified as a type of dysautonomia – dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system.

The change in heart rate and the autonomic function gives rise to several symptoms, including fatigue, brain fog, and shaking, in addition to lightheadedness when standing up.

Doctors define POTS as:

- A heart rate increase of 30 BPM within the first 10 minutes of standing for adults (40 BPM for children and teens)

- Or an increase in heart rate to over 120 BPM within the first 10 minutes of standing[ref]

These requirements define POTS as long as the person doesn’t have orthostatic hypotension, a condition where blood pressure initially drops when standing.

The Dysautonomia International website explains that POTS impacts 3 million people in the US and more around the world.

Symptoms of Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome:

POTS symptoms defined in research studies include[ref][ref][ref][ref][ref]:

- fatigue

- headaches, brain fog

- lightheaded, fainting, vertigo

- heart palpitations, chest pain

- exercise intolerance

- shaking, cold hands and feet

- abdominal pain, nausea, bloating, nerve pain

- diarrhea, constipation, bladder problems

POTS symptoms are often made worse by heat stress.

What happens to blood pressure when standing up?

When someone who does not have POTS stands up, the body goes through a series of regulatory changes that alter heart rate. Because blood pressure and heart rate regulation are automatic, we aren’t even aware that they are taking place.

- Upon standing, gravity causes blood to go from the chest to the lower abdomen and legs. Within the first 30 seconds of standing, there is a fluid shift between the blood vessels and the space in between the cells.

- This change in blood volume causes receptors in the heart to be activated and alters the heart’s stroke volume.

- All of this causes the heart rate to increase just a little bit normally. It also alters blood pressure slightly (decreased systolic BP, increased diastolic BP).[ref]

Thus, when standing up, a slight increase in heart rate and BP is normal.

What happens when a person with POTS stands up?

There are a couple of different scenarios of what is happening in people with POTS (more details below). But generally, POTS can be caused by low blood volume or by the blood vessels in the legs not constricting enough.[ref]

- Reduced blood volume:

If the person with POTS is hypovolemic – reduced blood volume – they usually have an elevated heart rate even when at rest. This heart rate elevation worsens upon sitting or standing, and the heart rate increases substantially. - Not enough vasoconstriction:

For someone with reduced vasoconstriction in the legs, the heart rate increases dramatically to maintain normal blood pressure. This increase could be worsened in high-heat conditions, causing more blood to flow to the skin.[ref]

Theories on the underlying causes of POTS:

Research points to several theories on what causes POTS, and it is likely that the individual causes of the symptoms can be different for different people.

Let’s look at a couple of the different systems that regulate heart rate and blood pressure, and then we will dive into some of the known causes of dysfunction in these systems.

The autonomic nervous system and blood regulation:

POTS is usually classified as a type of dysautonomia. Essentially, dysautonomia means a dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system. It is a catch-all term, with several chronic conditions falling under the umbrella of dysautonomia.[ref]

The autonomic nervous system controls involuntary functions in the body – including heart rate, blood pressure, and the motility of the digestive tract.

Blood pressure is tightly regulated through the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (called RAAS). The RAAS system balances out the volume of blood by regulating sodium and water levels. In the kidneys, this system can either increase sodium reabsorption or water reabsorption to alter blood volume in the body. (More water kept in the bloodstream = more blood volume.)[ref]

Angiotensin system and POTS:

For some people, the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system is involved in POTS. When RAAS dysfunction is involved in causing POTS, there can be an increase in plasma angiotensin II. This increase causes an imbalance in blood volume due to the kidneys not retaining enough sodium. Additionally, some researchers have found that there is inadequate ACE2 activity.[ref][ref]

Vasoconstriction and POTS:

Vasoconstriction is the tightening (constriction) of blood vessels, which increases blood pressure. This is controlled by the sympathetic nervous system.

Some people with POTS have issues with the sympathetic nervous system not working correctly in the feet and legs. When standing up, it can result in insufficient vasoconstriction (e.g., blood vessels are too relaxed). As a result, blood pools in the legs and feet, as well as the abdominal cavity. The lack of vasoconstriction and the pooling blood then kick the heart into high gear, pumping hard to make up for the lack of blood flow.[ref]

Sympathetic nervous system, NET, medications, and POTS: Hyperadrenergic

One branch of the autonomic nervous system is the sympathetic nervous system (fight-or-flight response).

The activation of the sympathetic nervous system releases norepinephrine. Norepinephrine (aka noradrenaline) functions as a neurotransmitter and a stress hormone in the body.

Adrenergic system and POTS:

A subset of people with POTS have what is known as the ‘hyperadrenergic’ form. When these people stand, their bodies release an excess of norepinephrine. It can cause heart palpitations, tremors, rapid heartbeat, feeling anxious, and increased blood pressure. Some patients with hyperadrenergic POTS also get headaches upon standing.[ref][ref]

Alternatively, instead of releasing excess norepinephrine, the body may not clear out the normal norepinephrine quickly enough. Or both could occur together.

Norepinephrine transporter, autonomic nervous system:

Alterations in the norepinephrine transporter (NET) can cause reduced clearance of norepinephrine, leaving the sympathetic nervous system in a state of excessive activation. Norepinephrine is the primary signaling neurotransmitter in the autonomic nervous system, where it controls heart rate. When norepinephrine is released into the synapse between neurons, the amount of norepinephrine available there is controlled by the norepinephrine transporter, NET.[ref]

In POTS, research points to an excess of norepinephrine signaling, and this could be due to decreased NET activity — essentially allowing too much norepinephrine to remain in the synapse.

Both rare mutations and more common gene variants that code for the norepinephrine transporter (SLC6A2 gene) are linked to POTS. Additionally, certain medications are NET inhibitors – some tricyclic antidepressants and certain ADHD medications.[ref]

Medications that impact NET may be helpful in POTS. For example, atomoxetine (Strattera) is an ADHD medication that targets the norepinephrine transporter. In a clinical trial, it has been shown to significantly increase the standing heart rate in POTS patients.[ref] Note that this may not be a good option for everyone. An animal study showed that atomoxetine increased histamine levels (in the brain).[ref]

Epigenetic changes and POTS:

Research points towards epigenetic modification of the SLC6A2 gene as a cause of POTS. Epigenetic changes are ways that genes can be turned off (or on) for transcription. In this case, the researchers think that epigenetic markers decrease the availability of the norepinephrine transporter in POTS.[ref]

Autoimmune involvement in POTS:

Research shows that for some people, POTS can be due to an autoimmune attack on either the adrenergic system or the renin-angiotensin system.[ref][ref] Both systems are important in heart rate and blood flow.

For example, a small study in 2018 found that most patients with POTS in their study had angiotensin II type 1 receptor antibodies (IgG) as well as adrenergic activation, showing an autoimmune activation of that receptor. Interestingly, losartan, a commonly used hypertension medication that acts on the angiotensin II receptor, reduced the receptor activity down to the same levels as the control.[ref]

Another recent study showed that patients with POTS were likely to have autoimmune activity towards the adrenergic receptors (α1 receptor, β2 receptor, cholinergic, and opioid receptor-like 1).[ref] The α1 and β2 adrenergic receptors are activated by epinephrine and norepinephrine, tying back to the norepinephrine disruption of the autonomic nervous system.[ref]

However, not everyone with POTS has autoimmune activity that interacts with the angiotensin receptors or the adrenergic receptors.

So far, we have autonomic dysfunction causing vasoconstriction or alterations to the angiotensin system or adrenergic receptors. But what initiates these changes?

Triggers of POTS:

Researchers have identified several different triggering events that can initiate POTS. Diseases and conditions linked to triggering POTS include:

- Autoimmune activation of the adrenergic system[ref][ref]

- Autoimmune activation of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor[ref]

- Mast cell activation[ref]

- Viral illness, infections, including covid and West Nile virus[ref][ref]

- linked to the HPV vaccine (more studies are needed on this to show causality)[ref]

- Concussions[ref]

- Surgery, bed rest[ref]

- Inflammatory disorders[ref]

Let’s dig into the research on a few of these triggers:

Vaccines and POTS:

One trigger for POTS for some individuals seems to be certain vaccines given to teens or adults. For example, there are dozens of case reports of POTS shortly following the HPV vaccine. Additionally, several studies followed some women after the HPV shot, finding an increase in dysautonomia and POTS.[ref][ref][ref][ref][ref]

Why would an HPV vaccine cause POTS in a minority of people? Some researchers point to an autoimmune response (adrenergic receptor antibodies) due to molecular mimicry with specific HPV peptides.[ref]

There are a lot of unanswered questions on the links between the HPV vaccine and POTS. Epidemiological studies often don’t find a statistical, population-wide link between the introduction of the HPV vaccine and the number of POTS diagnoses.[ref][ref] Additionally, some researchers point to media coverage as a cause for any post-vaccination symptom spikes.[ref]

Covid, long Covid, and POTS:

Interestingly, one of the mechanisms that causes POTS is a disturbance in the renin-angiotensin system, possibly due to inadequate ACE2 activity, which is one of the receptors used by the SARS-CoV-2 virus in causing Covid.[ref][ref][ref] POTS is a common autonomic disorder following Covid and in long Covid.[ref][ref]

Some researchers point to SARS-CoV-2 invading the central nervous system in POTS, while others point to the changes in endothelial function. Yet other research shows that neuroinflammation may be involved in POTS after a Covid infection.[ref][ref] Multiple case studies also report a new onset of POTS following the Covid mRNA vaccine.[ref][ref][ref]

Overlapping conditions: POTS + hEDS + MCAS + ME/CFS

POTS is a syndrome – meaning a collection of symptoms – rather than a specific disease. Thus, multiple diseases or chronic conditions can cause POTS symptoms.

While POTS can be a stand-alone diagnosis, there are several conditions that have a high frequency of overlap with POTS.

hEDS (hypermobility Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome):

Joint hypermobility is found in about 50% of teens with POTS, pointing to an overlap with what is called hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos.[ref][ref]

ME/CFS:

Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) is a chronic, debilitating condition with severe fatigue that doesn’t improve with rest, often along with other symptoms such as sleep disturbances, PEM, brain fog, light sensitivity, and more. A subset of patients with ME/CFS also have the POTS-like heart rate response upon standing. A study involving patients with ME/CFS plus POTS found that differences can be seen with tilt-table responses showing either a hyperadrenergic response or a venous pooling response.[ref]

Mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS):

MCAS involves the overactivation of mast cells, which are a type of immune system cell that releases histamine, trypsin, and inflammatory signals upon activation. MCAS symptoms can include hives, itching, nausea, gastrointestinal issues, headaches, mood swings, fatigue, respiratory symptoms, and alterations to blood pressure and heart rate. There’s a high rate of overlap – some studies showing 66% overlap – with MCAS and POTS.[ref]

Is POTS Genetic?

The big question with POTS, especially in long Covid or other post-viral illnesses, is why some people get it and others do not.

Research shows that certain genetic variants increase the susceptibility (or risk) to POTS. There isn’t a single genetic mutation that causes POTS. Rather, POTS is a syndrome that can have its genetic roots in various genes. Understanding where your genetic susceptibility lies may help you find your best treatment options.

| Gene | Function/Pathway | Key Variant(s) | Effect on POTS Risk/Symptoms | Data Availability in Consumer Tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLA-DQB1*0609 | Immune system/self-recognition | *0609 | 8x increased risk | Not available |

| SLC6A2 | Norepinephrine transporter | rs5569 | Increased susceptibility | Available |

| GNB3 | Signal transduction, blood pressure | C825T | Alters heart rate response | Available |

| NOS3 | Nitric oxide synthesis, vasodilation | rs2070744, others | Some protective, some increase risk | Some available |

Genetic mutations linked to POTS:

For many people, an autoimmune condition (adrenergic system, angiotensin II receptor) triggers POTS, and genetic variants can increase the risk of certain autoimmune conditions. The HLA genes code for an important part of our adaptive immune system. They help the body understand what is foreign (bacteria, viruses) and needs to be attacked. They also help the body understand which tissue is ‘self’ and should be left alone by the immune system. One POTS risk factor is an HLA variant that is not included in 23andMe or AncestryDNA data. A study in 2019 identified the HLA-DQB1*0609 serotype as increasing the risk of POTS by over 8-fold.[ref]

Other genetic variants increase susceptibility to POTS in different ways. The genes that have been identified so far by researchers include nitric oxide genes, norepinephrine (noradrenaline) transporters, and the beta2-adrenergic receptor – all of which impact blood volume regulation. These are all included in the Genotype Report section below.

Sympathetic nervous system:

The SLC6A2 gene codes for a norepinephrine transporter (NET), which removes norepinephrine from the junction between sympathetic nerves. Norepinephrine transporter impairment is linked to depression, panic disorder, tachycardia, and POTS.[ref] Rare mutations in the SLC6A2 gene have been strongly linked to POTS, and a more common variant increases susceptibility a little bit.

The GNB3 gene codes for part of a G-protein that is involved in signal transduction. It can impact a lot of systems in the body, including metabolism and blood pressure. Specifically, a common variant in GNB2 has been shown to interact with the vagus nerve in regulating blood pressure in pots. This variant causes “enhanced vagal withdrawal of the heart” in relation to POTS.[ref]

Vasoconstriction of blood vessels:

The NOS3 gene codes for endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase enzyme, which is essential for relaxing blood vessels. Nitric oxide production in the lining of the blood vessels helps to regulate blood flow. A common genetic variant in the NOS3 gene is protective against POTS. Other NOS3 variants, not included in 23andMe or AncestryDNA data, are also linked to POTS.

Epigenetics and POTS:

Epigenetics refers to alterations in how the genetic code is turned on or off for translation. In a nutshell, the nucleus of every cell contains the complete genome, but only certain genes remain essential for that cell to function. Epigenetic markers control how often a gene is translated into its protein.

Studies showed that people with POTS were more likely to have epigenetic modifications that reduced the function of the norepinephrine transporter (SLC6A2 gene).[ref][ref] This goes hand-in-hand with the research showing that people with genetic variants that reduce the function of the SLC6A2 gene are also more susceptible to POTS.

Genotype Report: POTS

Below are several genetic variants linked to an increased (or decreased) susceptibility to POTS. These genes don’t cause POTS by themselves, but instead, the variants cause an increased risk that combines with an environmental trigger, resulting in the syndrome.

Lifehacks for POTS: Diet, supplements, apps, and treatments

Decreasing POTS symptoms:

Research studies show that the following are recommended for POTS, but please talk with your doctor before making any changes – including lifestyle changes.

- Increase your fluid intake:

Hypovolemia, or lower levels of blood volume, may be helped, in part, by increasing the amount of water – or electrolyte sports drink – that you consume.[ref] - Increased sodium intake:

Similar to increasing fluid intake, if your sodium intake is low or your electrolyte balance is off, it can affect blood volume.[ref] Often, people with POTS are encouraged to drink sports drinks such as Gatorade. - Compression socks:

If your blood pools in your lower extremities, compression socks or compression leggings may help.

Mast cell activation and POTS:

Check out the full article on mast cell activation syndrome, along with the lifehacks section there. Reducing mast cell activation through supplements, such as luteolin or quercetin, may help reduce symptoms.

Specific interventions with genetic connections:

These genetic connections are theoretical, but they may give you a starting point for talking with your doctor or doing more research.

Vagal nerve stimulation:

A clinical trial showed that transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation significantly reduced POTS symptoms compared to a sham (placebo) treatment.[ref] The GNB3 T allele is associated with an increased risk of POTS and links to vagal nerve stimulation in the heart.

Beta-blockers:

Talk with your doctor about whether beta-blockers (β2 adrenergic receptor antagonists) are an option for you. Clinical trials show that they are helpful for some people with POTS.[ref] The ADRB2 gene codes for the beta2-adrenergic receptor and the SLC6A2 gene encodes the norepinephrine transporter. Both may be relevant for beta-blockers.[ref]

Increase NOS3:

Reduced nitric oxide activity is associated with POTS for some people.[ref] BH4 (tetrahydrobiopterin) is an essential cofactor for nitric oxide production. Your body naturally produces BH4, and under normal conditions, it gets recycled and reused in the cell. But when oxidative stress is high (excess reactive oxygen species), it can be used up more quickly.[ref] Studies show that Vitamin C increases nitric oxide through increasing BH4 bioavailability.[ref]

Curcumin for NOS3?

Similarly, curcumin supplementation has been shown to increase NO by reducing oxidative stress.[ref] A clinical trial of 2,000 mg/day of curcumin had beneficial effects on increasing nitric oxide in relation to endothelial function tests for cardiovascular disease.[ref]

Diet and Supplements for POTS Syndrome:

The recommendations and studies seem to vary a lot on specific dietary interventions. For example, some caffeine constricts the blood vessels and can be helpful in certain situations, but caffeine worsens POTS for others.

Overall, a healthy diet with fresh vegetables and fruits, fish, and/or grass-fed meat should help meet your needs for vitamins.

Low iron or low vitamin D levels are also linked to an increased risk for POTS in teens.[ref][ref] It is easy to check both your iron and vitamin D levels with a quick blood test. You can order tests online (e.g., UltaLab tests) or through your doctor.

Caution with exercise:

People with POTS are often ‘deconditioned’ due to fatigue and not being able to exercise. Researchers recommend mild to moderate exercise for short periods several times a week to reverse the deconditioning.[ref] Talk with your doctor to figure out a plan that will work best for you.

POTS and Heart Rate Apps:

Several different heart rate apps are available for both Android and iPhone. Some apps, such as Cardiogram, integrate with Apple Watch to track heart rate. The Instant Heart Rate app for the iPhone is easy to use and has good ratings.

Talk with your doctor about:

An angiotensin II receptor blocker, Losartan, may also be something to talk with your doctor about. Several studies show that it could be effective for some individuals with POTS if they have autoimmune activation of the angiotensin II receptor.[ref][ref][ref]

Natural Supplements for POTS:

Get enough B12:

One study noted that teens with POTS were about three times more likely to have low vitamin B12 levels.[ref] Good food sources of B12 include liver, fish, meat, poultry, eggs, and dairy products. If you are planning to supplement with methylB12, be sure to check your COMT gene first. People with slow COMT may want to choose a different type of B12.

Thiamine:

Another study found that a (small) percentage of POTS patients had vitamin B1 (thiamine) deficiency, and supplementing with B1 resolved POTS symptoms.[ref]

Related article: Thiamine: Genomics and cellular function

Possible additional genetic connections:

BH4: Genetic variants can decrease your ability to produce enough BH4 when the body is under stress. This can affect NOS3.

Salt-sensitivity: Some people are more likely to have an increase in blood pressure due to salt intake.

| Gene | RS ID | Effect Allele | Your Genotype | Notes About Effect Allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGTR1 | rs4524238 | A | -- | lower blood pressure with a low-salt diet |

| SLC4A5 | rs7571842 | A | -- | blood pressure more likely to be sensitive to higher salt diet |

| SLC4A5 | rs10177833 | C | -- | blood pressure less likely to be sensitive to salt |

| ACE | rs4343 | G | -- | A/G: ACE deletion/insertion, blood pressure somewhat sensitive to high salt; G/G: ACE deletion/deletion —blood pressure not as sensitive to salt |

| LSS | rs2254524 | A | -- | a low salt diet more likely to work for high blood pressure |

| NPPA | rs5063 | T | -- | blood pressure more susceptible to salt consumption |

| ADD1 | rs4961 | T | -- | blood pressure likely to be salt-sensitive |

| SGK1 | rs2758151 | C | -- | C/C: blood pressure sensitive to salt intake; C/T: blood pressure not as salt-sensitive |

| LSD1 | rs587168 | A | -- | blood pressure increases significantly with high dietary salt |

| UMOD | rs4293393 | G | -- | protective against salt-sensitive blood pressure, increased kidney stone risk |

| UMOD | rs13333226 | G | -- | protective against salt-sensitive blood pressure |

Mast cells: MCAS, genetics, and solutions: There is an overlap between mast cell activation syndrome and POTS.[ref]

MTHFR: While likely not a ’cause’ of POTS, optimizing the methylation cycle genes could help with epigenetic causes of POTS. Check if you need more folate (methyl folate) due to MTHFR variants.

| Gene | RS ID | Effect Allele | Your Genotype | Notes About Effect Allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTHFR C677T | rs1801133 | A | -- | 40-70% decrease in MTHFR enzyme function (folate metabolism) |

| MTHFR A1298C | rs1801131 | G | -- | 10-20% decrease in MTHFR enzyme function (folate metabolism) |

Thiamine: Rare variants can increase your need for thiamine.

| Gene | RS ID | Effect Allele | Your Genotype | Notes About Effect Allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLC19A2 | rs2038024 | C | -- | Increased risk of venous thromboembolism |

| SLC19A2 | rs28937595 | A | -- | Mutation linked to thiamine-responsive megoblastic anemia (rare) |

| SLC19A2 | rs121908540 | A | -- | Mutation linked to thiamine-responsive megoblastic anemia (rare) |

| SLC19A2 | rs74315373 | A | -- | Mutation linked to thiamine-responsive megoblastic anemia (rare) |

| SLC19A2 | rs74315374 | T | -- | Mutation linked to thiamine-responsive megoblastic anemia (rare) |

| SLC19A2 | rs74315375 | T | -- | Mutation linked to thiamine-responsive megoblastic anemia (rare) |

| SLC19A3 | rs121917884 | C | -- | Mutation related to basal ganglia disease (rare) |

| SLC19A3 | rs121917882 | A | -- | Mutation related to basal ganglia disease (rare) |

| SLC22A1 | rs72552763 | D | -- | reduced thiamine transport |

| TPK1 | rs371271054 | C | -- | Carrier of thiamine-related mutation |

| SLC25A19 | rs119473030 | G | -- | Mutation for microcephaly |

| PHDC | rs28933391 | A | -- | AA = pathogenic for Pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency (Important) |

| PHDC | rs28935769 | C | -- | CC = pathogenic for Pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency (important) |

| BCKDHB | i3002808 | C | -- | Maple syrup urine disease, thiamine responsive (rare) |

| BCKDHB | rs386834233 | A | -- | Maple syrup urine disease, thiamine responsive (rare) |

| BCKDHB | rs74103423 | A | -- | Maple syrup urine disease, thiamine responsive (rare) |

| SLC25A19 | rs387906944 | G | -- | carrier of a rare mutation linked to thiamine metabolism dysfunction syndrome-4 |

| BCKDHB | i4000422 | A | -- | Maple syrup urine disease, thiamine responsive (rare) |

| SLC19A3 | i5006222 | C | -- | Mutation related to basal ganglia disease (rare) |

| SLC19A2 | i5000802 | T | -- | Mutation linked to thiamine-responsive megoblastic anemia (rare) |

| SLC19A2 | rs6656822 | T | -- | Higher SCL19A2 activity |

Magnesium genes: Check to make sure that you aren’t more likely to have low magnesium levels.

| Gene | RS ID | Effect Allele | Your Genotype | Notes About Effect Allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRPM6 | rs3750425 | T | -- | lower serum magnesium levels |

| TRPM6 | rs2274924 | C | -- | lower serum magnesium levels |

| TRPM6 | rs121912625 | A | -- | rare mutation linked to hypomagnesia |

| TRPM7 | rs8042919 | A | -- | increased sensitivity to low magnesium levels, |

| CNNM2 | rs12413409 | A | -- | decreased risk of hypertension and heart disease (good!) |

| CNNM2 | rs11191548 | C | -- | decreased risk of hypertension (good!) |

| CNNM2 | rs7914558 | G | -- | GG only: decreased gray matter (on average) |

| ATP2B1 | rs7965584 | G | -- | lower serum magnesium levels |

| SHROOM3 | rs13146355 | A | -- | slightly higher serum magnesium levels |

| SLC41A1 | rs708727 | A | -- | increased risk of Parkinson’s (possibly indicates less magnesium in the brain) |

| SLC41A1 | rs823156 | G | -- | protective against Parkinson’s (possibly indicates more magnesium in the brain) |

Histamine Intolerance: You may also want to check on Histamine Intolerance and see if a low-histamine diet may help with POTS symptoms.

| Gene | RS ID | Effect Allele | Your Genotype | Notes About Effect Allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOC1 | rs10156191 | T | -- | Reduced production of DAO |

| AOC1 | rs2052129 | T | -- | Reduced production of DAO |

| AOC1 | rs1049742 | T | -- | Reduced production of DAO |

| AOC1 | rs1049793 | G | -- | Reduced production of DAO |

| AOC1 | rs2071514 | A | -- | possibly slightly higher DAO |

| HMNT | rs1050891 | A | -- | Reduced breakdown of serum histamine |

| HMNT | i3000469 | T | -- | Reduced breakdown of serum histamine |

| HMNT | rs2071048 | T | -- | T/T: Reduced breakdown of serum histamine (common) |

| HMNT | rs11558538 | T | -- | Reduced breakdown of serum histamine |

| HDC | rs2073440 | G | -- | Decreased histamine production |

| HDC | rs267606861 | A | -- | rare pathogenic mutation, linked to Tourettes |

| HRH1 | rs901865 | T | -- | Increased H1 receptor, increased asthma risk |

| HRH2 | rs2067474 | A | -- | Decreased H2 receptor |

| HRH4 | rs11662595 | G | -- | decreased HRH4 activation (receptor dysfunction), increased risk of progression in non-small cell lung cancer |

| MTHFR | rs1801133 | A | -- | MTHFR C677T, decreased enzyme function, affects methylation cycle |

| MTHFR | rs1801131 | G | -- | MTHFR A1298C, slightly decreased enzyme function, slightly affects methylation cycle |

Genetics and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS mutations): Ehlers-Danlos syndrome goes hand-in-hand with POTS for some people. (see the article for a long list of mutation)

Related Articles and Topics:

Ehlers Danlos Syndrome Genes:

This article explores the research on Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and explains the genetic mutations that cause some of the subtypes of the disorder. You can check your genetic data (23andMe version 5 data) and learn more about how collagen disorders affect people.

Histamine Intolerance

Chronic headaches, sinus drainage, itchy hives, problems staying asleep, and heartburn — all of these symptoms can be caused by the body not breaking down histamine very well. Your genetic variants could be causing you to be more sensitive to foods high in histamine. Check your genetic data to see if this could be at the root of your symptoms.

Mast cells: MCAS, genetics, and solutions

Mast Cell Activation Syndrome, or MCAS, is a recently recognized disease involving mast cells that are misbehaving in various ways. Symptoms of MCAS can include abdominal pain, nausea, itching, flushing, hives, headaches, heart palpitations, anxiety, brain fog, and anaphylaxis.

HLA-B27: Genetic Variant That Increases Susceptibility to Autoimmune Diseases

Our immune system does an awesome job (most of the time) of fighting off pathogenic bacteria and viruses. But to fight off these pathogens, the body needs to know that they are the bad guys. This is where the HLA system comes in. This article covers background information on HLA-B27 and the genetic variants available in 23andMe or AncestryDNA data.

References:

Anjum, Ibrar, et al. “Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome and Its Unusual Presenting Complaints in Women: A Literature Minireview.” Cureus, vol. 10, no. 4, p. e2435. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.2435. Accessed 12 Apr. 2022.

Bayles, Richard, et al. “Epigenetic Modification of the Norepinephrine Transporter Gene in Postural Tachycardia Syndrome.” Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, vol. 32, no. 8, Aug. 2012, pp. 1910–16. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.244343.

Blitshteyn, Svetlana, et al. “Autonomic Dysfunction and HPV Immunization: An Overview.” Immunologic Research, vol. 66, no. 6, Dec. 2018, pp. 744–54. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12026-018-9036-1.

Bonamichi-Santos, Rafael, et al. “Association of Postural Tachycardia Syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome with Mast Cell Activation Disorders.” Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America, vol. 38, no. 3, Aug. 2018, pp. 497–504. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iac.2018.04.004.

Boris, Jeffrey R., and Thomas Bernadzikowski. “Demographics of a Large Paediatric Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome Program.” Cardiology in the Young, vol. 28, no. 5, May 2018, pp. 668–74. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951117002888.

Brinth, Louise, et al. “Suspected Side Effects to the Quadrivalent Human Papilloma Vaccine.” Danish Medical Journal, vol. 62, no. 4, Apr. 2015, p. A5064.

Brinth, Louise S., et al. “Orthostatic Intolerance and Postural Tachycardia Syndrome as Suspected Adverse Effects of Vaccination against Human Papilloma Virus.” Vaccine, vol. 33, no. 22, May 2015, pp. 2602–05. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.03.098.

Bryarly, Meredith, et al. “Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome: JACC Focus Seminar.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, vol. 73, no. 10, Mar. 2019, pp. 1207–28. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.059.

Chandler, Rebecca E., et al. “Current Safety Concerns with Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: A Cluster Analysis of Reports in VigiBase®.” Drug Safety, vol. 40, no. 1, Jan. 2017, pp. 81–90. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-016-0456-3.

Dysautonomia International: Dysautonomia Awareness, Dysautonomia Advocacy, Dysautonomia Advancement. http://www.dysautonomiainternational.org/. Accessed 12 Apr. 2022.

Dysautonomia International: Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome. http://www.dysautonomiainternational.org/page.php?ID=30. Accessed 12 Apr. 2022.

Fedorowski, Artur, et al. “Antiadrenergic Autoimmunity in Postural Tachycardia Syndrome.” Europace: European Pacing, Arrhythmias, and Cardiac Electrophysiology: Journal of the Working Groups on Cardiac Pacing, Arrhythmias, and Cardiac Cellular Electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology, vol. 19, no. 7, July 2017, pp. 1211–19. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euw154.

Fountain, John H., and Sarah L. Lappin. “Physiology, Renin Angiotensin System.” StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, 2022. PubMed, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470410/.

Garland, Emily M., et al. “Endothelial NO Synthase Polymorphisms and Postural Tachycardia Syndrome.” Hypertension (Dallas, Tex.: 1979), vol. 46, no. 5, Nov. 2005, pp. 1103–10. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.0000185462.08685.da.

Green, Elizabeth A., et al. “Effects of Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibition on Postural Tachycardia Syndrome.” Journal of the American Heart Association, vol. 2, no. 5, Sept. 2013, p. e000395. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.113.000395.

Ikeda, Shu-Ichi, et al. “Suspected Adverse Effects after Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: A Temporal Relationship.” Immunologic Research, vol. 66, no. 6, Dec. 2018, pp. 723–25. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12026-018-9063-y.

Kanjwal, Khalil, et al. “Clinical Presentation and Management of Patients with Hyperadrenergic Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome. A Single Center Experience.” Cardiology Journal, vol. 18, no. 5, 2011, pp. 527–31. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.5603/cj.2011.0008.

Khan, Abdul Waheed, et al. “NET Silencing by Let-7i in Postural Tachycardia Syndrome.” JCI Insight, vol. 2, no. 6, Mar. 2017, p. e90183. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.90183.

Li, Hongliang, et al. “Autoimmune Basis for Postural Tachycardia Syndrome.” Journal of the American Heart Association, vol. 3, no. 1, Feb. 2014, p. e000755. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.113.000755.

Marques, F. Z., et al. “A Polymorphism in the Norepinephrine Transporter Gene Is Associated with Affective and Cardiovascular Disease through a MicroRNA Mechanism.” Molecular Psychiatry, vol. 22, no. 1, Jan. 2017, pp. 134–41. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.40.

Miranda, Nicole A., et al. “Activity and Exercise Intolerance After Concussion: Identification and Management of Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome.” Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy, vol. 42, no. 3, July 2018, pp. 163–71. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1097/NPT.0000000000000231.

Mustafa, Hossam I., et al. “Abnormalities of Angiotensin Regulation in Postural Tachycardia Syndrome.” Heart Rhythm, vol. 8, no. 3, Mar. 2011, pp. 422–28. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.11.009.

Nakao, Ryota, et al. “GNB3 C825T Polymorphism Is Associated with Postural Tachycardia Syndrome in Children.” Pediatrics International: Official Journal of the Japan Pediatric Society, vol. 54, no. 6, Dec. 2012, pp. 829–37. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-200X.2012.03707.x.

Raj, Satish R. “The Postural Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS): Pathophysiology, Diagnosis & Management.” Indian Pacing and Electrophysiology Journal, vol. 6, no. 2, Apr. 2006, pp. 84–99. PubMed Central, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1501099/.

Segal, Yahel, and Yehuda Shoenfeld. “Vaccine-Induced Autoimmunity: The Role of Molecular Mimicry and Immune Crossreaction.” Cellular and Molecular Immunology, vol. 15, no. 6, June 2018, pp. 586–94. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1038/cmi.2017.151.

Shibao, Cyndya, et al. “Hyperadrenergic Postural Tachycardia Syndrome in Mast Cell Activation Disorders.” Hypertension (Dallas, Tex.: 1979), vol. 45, no. 3, Mar. 2005, pp. 385–90. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.0000158259.68614.40.

Skufca, J., et al. “Incidence Rates of Guillain Barré (GBS), Chronic Fatigue/Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease (CFS/SEID) and Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) Prior to Introduction of Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) Vaccination among Adolescent Girls in Finland, 2002–2012.” Papillomavirus Research, vol. 3, Mar. 2017, pp. 91–96. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pvr.2017.03.001.

Stewart, Julian M., et al. “Defects in Cutaneous Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 and Angiotensin-(1-7) Production in Postural Tachycardia Syndrome.” Hypertension, vol. 53, no. 5, May 2009, pp. 767–74. ahajournals.org (Atypon), https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.127357.

Thomsen, Reimar Wernich, et al. “Hospital Records of Pain, Fatigue, or Circulatory Symptoms in Girls Exposed to Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: Cohort, Self-Controlled Case Series, and Population Time Trend Studies.” American Journal of Epidemiology, vol. 189, no. 4, Apr. 2020, pp. 277–85. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwz284.

Vojdani, Aristo, and Datis Kharrazian. “Potential Antigenic Cross-Reactivity between SARS-CoV-2 and Human Tissue with a Possible Link to an Increase in Autoimmune Diseases.” Clinical Immunology (Orlando, Fla.), vol. 217, Aug. 2020, p. 108480. PubMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2020.108480.

Yu, Xichun, et al. “Angiotensin II Type 1 Receptor Autoantibodies in Postural Tachycardia Syndrome.” Journal of the American Heart Association, vol. 7, no. 8, Apr. 2018, p. e008351. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.008351.

Zhang, Qingyou, et al. “Clinical Features of Hyperadrenergic Postural Tachycardia Syndrome in Children: Hyperadrenergic POTS.” Pediatrics International, vol. 56, no. 6, Dec. 2014, pp. 813–16. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.12392.